Bastille

| Bastille | |

|---|---|

| Paris, France | |

A view of the Bastille |

|

| Type | Medieval fortress, prison |

| Built | 1370–1383 |

| Built by | Charles V of France |

| Demolished | 1789 |

| Current condition |

remains in Metro station |

| Events | French Revolution |

The Bastille (French pronunciation: [bastij]) was a fortress-prison in Paris, known formally as Bastille Saint-Antoine—Number 232, Rue Saint-Antoine—best known today because of the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, which along with the Tennis Court Oath is considered the beginning of the French Revolution. The event was commemorated one year later by the Fête de la Fédération. The French national holiday, celebrated annually on 14 July is officially the Fête Nationale, and officially commemorates the Fête de la Fédération, but it is commonly known in English as Bastille Day. Bastille is a French word meaning "castle" or "stronghold", or "bastion"; used with a definite article (la Bastille in French, the Bastille in English), it refers to the prison.

Contents |

Early history of the Bastille

The Bastille was built as the Bastion de Saint-Antoine during the Hundred Years' War. The Bastille originated as the Saint-Antoine gate, but from 1370–1383 this gate was extended to create a fortress to defend the east end of Paris and the Hôtel Saint-Pol royal palace. After the war, it was reused as a state prison, with Louis XIII the first king to send prisoners there.

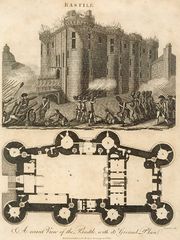

The Bastille was built as an irregular rectangle with eight towers, 70 meters (220 ft) long, 30 meters (90 ft) wide, with towers and walls 25 meters (80 ft) high, surrounded by a broad moat. Originally there were two courtyards inside and residential buildings against the walls. Pairs of towers on the east and west facades served as gates through which the rue Saint-Antoine passed. In the 15th century, these were blocked up, and a new city gate was created to the north on the present day rue de la Bastille. A bastion on the eastern approaches was built later. A very significant military feature of the building was that the walls and towers were of the same height and width and connected by a broad terrace. This enabled soldiers on the wall head to rapidly move to a threatened sector of the fortress without having to descend inside the towers, as well as allowing placement of artillery. A similar provision can be seen today at Château de Tarascon.

Storming

The archives of the Bastille show that the building largely held common criminals (forgers, embezzlers, swindlers, etc.), as well as people imprisoned for religious reasons (Huguenots) and those responsible for printing or writing forbidden pamphlets.[1] People of high rank were sometimes held there too, and so the prison (which could only hold a little over 50 people) was far less sordid a place than most of the Parisian prisons. But the secrecy maintained around the Bastille and its prisoners gave it a sinister reputation.

The confrontation that led to the people of Paris storming the Bastille on 14 July 1789, following several days of disturbances, resulted from the fact that gunpowder and arms had been stored there, and the people (whose fears had been raised by a number of rumors) demanded access to these. The later idea that they wanted to free the prisoners (only 7 of whom remained) has been discounted. The regular garrison consisted of 82 invalides (veteran soldiers no longer capable of service in the field) under Governor Bernard-René de Launay. They had however been reinforced by a detachment of 32 grenadiers from one of the Swiss mercenary regiments summoned to Paris by the King shortly before 14 July.

A crowd of around 8800 men and women gathered outside around mid-morning, calling for the surrender of the prison, the removal of the guns and the release of the arms and gunpowder. Two people chosen to represent those gathered were invited into the fortress and slow negotiations began.

In the early afternoon around 1:00, the crowd broke into the undefended outer courtyard and the chains on the drawbridge to the inner courtyard were cut. A spasmodic exchange of gunfire began; in mid-afternoon the crowd was reinforced by mutinous Gardes Françaises of the Royal Army, and two cannons, all of which were originally supposed to help the governor protect the prison. De Launay ordered a ceasefire; in spite of his surrender demands being refused, he capitulated and the vainqueurs swept in to take control of the fortress at around 5:30.

When the rioters entered the Bastille, they collected cartridges and gunpowder for their weapons and then freed the seven prisoners (which they had to do by breaking down the doors, since the keys had already been taken off and paraded through the streets). Later, the governor and some of the guards of the Bastille were murdered under chaotic circumstances, despite having surrendered under a flag of truce, and their heads paraded on pikes.

As a symbolic gesture, the key to the west portal of the Bastille was presented on March 17, 1790 by Marquis de Lafayette to George Washington and is displayed in George Washington's home at Mount Vernon.[2]

Demolition

The propaganda value of the Bastille was quickly seized upon, notably by the showy entrepreneur Pierre-François Palloy, "Patriote Palloy". The fate of the Bastille was uncertain, but Palloy was quick to establish a claim, organising a force of demolition men around the site on the 15th. Over the next few days many notables visited the Bastille and it seemed to be turning into a memorial. But Palloy secured a license for demolition from the Permanent Committee at the Hôtel de Ville and quickly took complete control.

Pierre-François Palloy secured a fair budget and his crew grew in number. He had control over all aspects of the work and the workers, even to the extent of having two hanged for murder. Palloy put much effort into continuing the site as a paying attraction and producing a huge range of souvenirs, including much of the rubble. The actual demolition proceeded apace; by November, 1789, the structure was largely demolished. The cut stones of the fortress were used in the construction of the Pont de la Concorde.

The area today

The former location of the fort is currently called the Place de la Bastille. It is home to the Opéra Bastille. The large ditch (fossé) behind the fort has been transformed into a marina for pleasure boats, the Bassin de l'Arsenal, to the south, and a covered canal, the Canal Saint Martin, extending north from the marina beneath the vehicular roundabout that borders the location of the fort.

Some undemolished remains of one tower of the fort were discovered during excavation for the Métro (rail mass-transit system) in 1899, and were moved to a park (the Square Henri-Galli) a few hundred meters away, where they are displayed today. The original outline of the fort is also marked on the pavement of streets and sidewalks that pass over its former location, in the form of special paving stones. A cafe and some other businesses largely occupy the location of the fort, and the rue Saint Antoine passes directly over it as it opens onto the roundabout of the Bastille.

Bastille Prisoners in Fiction

- Comte de Rochefort (The Three Musketeers, Twenty Years After)

- Doctor Alexander Manette (A Tale of Two Cities)

- M. Thénardier (Les Miserables)

- Philippe (The Man in the Iron Mask)

References

- Lorentz, Phillipe; Dany Sandron (2006). Atlas de Paris au Moyen Âge. Paris: Parigramme. pp. 238 pp. ISBN 2840964023.

- ↑ "Archives de la Bastille" collected by francais Ravaisson Mollien, printed by Paris : A. Durand et Pedone-Lauriel, 1866-1904

- ↑ http://www.mountvernon.org/virtualnonflash/1Floor/bastilleKey.htm

External links

- Remains of the Bastille - photo of the salvaged remains of one tower, with a brief description

- À bas la Bastille!: how the Encyclopædia Britannica has written about the Bastille in various editions since 1768.