Cahokia

| Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category III (Natural Monument)

|

|

|

|

| Location | St. Clair County, Illinois, USA |

| Nearest city | Collinsville, Illinois |

| Area | 2,200 acres (8.9 km²) |

| Governing body | Illinois Historic Preservation Agency |

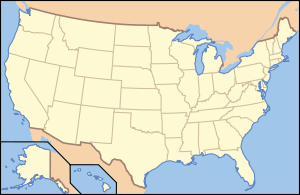

Cahokia (pronounced /kəˈhoʊki.ə/) Mounds State Historic Site is the area of an ancient indigenous city (ca 600–1400 CE) near Collinsville, Illinois. In the American Bottom floodplain, it is across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri. The 2,200-acre (8.9 km2) site included 120 man-made earthwork mounds over an area of six square miles, although only 80 survive.[1] Cahokia Mounds is the largest archaeological site related to the Mississippian culture, which developed advanced societies in central and eastern North America beginning more than five centuries before the arrival of Europeans.[2]

It is a National Historic Landmark and designated site for state protection. In addition, it is one of only twenty World Heritage Sites in the territory of the United States. It is the largest prehistoric earthen construction in the Americas north of Mexico.[1]

Contents |

World Heritage Site

| Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Reference | 198 |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1982 (6th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

Cahokia Mounds was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 19, 1964, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.[3] In 1982 UNESCO designated Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site a World Heritage Site. The park protects 2200 acres (8.9 km²), and is the focus of ongoing archaeological research. This is among only twenty cultural World Heritage Sites in the United States and the only one in Illinois, as designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).[4]

History

Cahokia was settled around 600 CE during the Late Woodland period, and mound building at this location began with the Emergent Mississippian cultural period, about the 9th century CE.[5] The inhabitants left no written records beyond symbols on pottery, shell, copper, wood, and stone, but the elaborately planned community, woodhenge, mounds, and burials reveal a complex and sophisticated society.[6] The city's original name is unknown.

The original site contained 120 earthen mounds over an area of six square miles, although only 80 survive today. To achieve that, thousands of workers over decades moved more than an "estimated 55 million cubic feet of earth in woven baskets to create this network of mounds and community plazas. Monks Mound, for example, covers 14 acres, rises 100 feet, and was topped by a massive 5,000 square-foot building another 50 feet high."[1]

The Mounds were named after a clan of historic Illiniwek people living in the area when the first French explorers arrived in the 1600s. As this was centuries after Cahokia was abandoned by its original inhabitants, the Cahokia were not necessarily descendants of the original Mississippian-era people. Scholars do not know which Native American groups are the living descendants of the people who originally built and lived at the Mound site, although many are plausible.

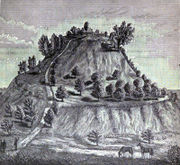

Monks Mound

Monks Mound is the largest structure and central focus of the city: a massive structure with four terraces, 10 stories tall, and the largest man-made earthen mound north of Mexico. Facing south, it is 92 feet (28 m) high, 951 feet (290 m) long and 836 feet (255 m) wide [7].

Excavation on the top of Monks Mound has revealed evidence of a large building, likely a temple or the residence of the paramount chief, seen throughout the city. This building was about 105 feet (32 m) long and 48 feet (15 m) wide, and could have been as much as 50 feet (15 m) high. It was about 5,000 square feet (460 m2).

The east and northwest sides of Monks Mound were twice excavated in August 2007 during an attempt to avoid erosion due to slumping.[8]

Woodhenge

Woodhenge, a circle of posts used to make astronomical sightings, stood to the west of Monk's Mound. Archaeologists discovered Woodhenge during excavation of the site and noted that the placement of posts marked solstices and equinoxes, like its namesake, Stonehenge.[9][10] Detailed analytical work supports the hypothesis that the placement of these posts was by design.[11] The structure was rebuilt several times during the urban center's roughly 300-year history. Evidence of another Woodhenge was discovered near Mound 72, to the south of Monks Mound.

According to Chappell, "A beaker[12] found in a pit near the winter solstice post bore a circle and cross symbol that for many Native Americans symbolizes the Earth and the four cardinal directions. Radiating lines probably symbolized the sun, as they have in countless other civilizations."[13] (Cahokia's Woodhenge is not to be confused with another site of the same name that exists in the United Kingdom).

Urban landscape

A 19-hectare (190,000 m²) Grand Plaza spreads out to the south of Monk's Mound. Researchers originally thought the flat, open terrain in this area reflected Cahokia's location on the Mississippi's alluvial flood plain. Instead, their soil studies showed that the landscape was originally undulating. It had been expertly and deliberately leveled and filled by the city's inhabitants. It is part of the sophisticated engineering displayed throughout the site. The Grand Plaza of Cahokia measured 40 acres (16 ha). It was used for large ceremonies and gatherings, as well as for ritual games, such as chunkey. Along with the Grand Plaza to the south, three other very large plazas surround Monks Mound in the cardinal directions to the east, west, and north.

A wooden stockade with a series of defensive bastions or watchtowers at regular intervals formed a two-mile (3 km)-long enclosure around Monks Mound, the Grand Plaza, and some of the elite residences. Archaeologists found evidence of the stockade during excavation of the area and indications that it was rebuilt several times. The stockade separated Cahokia's main ceremonial precinct from other parts of the city. Its bastions showed that it was also built for defense.

Beyond Monks Mound, as many as 120 more mounds stood at varying distances from the city center. To date, 109 mounds have been located, 68 of which are in the park area. The mounds are divided into several different types: platform, conical, ridge-top, etc.. Each appeared to have had its own meaning and function. In general terms, the city center seems to have been laid out in a diamond-shaped pattern approximately a mile (1.6 km) from end to end, while the entire city is five miles (8 km) across from east to west.

Ancient city

Cahokia was the most important center for the peoples known today as Mississippians. Their settlements ranged across what is now the Midwest, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. Cahokia was located in a strategic position near the confluence of the Mississippi, Missouri and Illinois rivers. It maintained trade links with communities as far away as the Great Lakes to the north and the Gulf Coast to the south, trading in such exotic items as copper, Mill Creek chert,[14] and whelk shells. Mississippian culture pottery and stone tools in the Cahokian style were found at the Silvernale site near Red Wing, Minnesota, and materials and trade goods from Pennsylvania, the Gulf Coast and Lake Superior have been excavated at Cahokia.

At the high point of its development, Cahokia was the largest urban center north of the great Mesoamerican cities in Mexico. Although it was home to only about 1,000 people before ca. 1050, its population grew explosively after that date. Archaeologists estimate the city's population at between 8,000 and 40,000 at its peak, with more people living in outlying farming villages that supplied the main urban center. In 1250, its population was larger than that of London, England.

If the highest population estimates are correct, Cahokia was larger than any subsequent city in the United States until about 1800, when Philadelphia's population grew beyond 40,000.

Mound 72

During excavation of Mound 72, a ridge-top burial mound south of Monk's Mound, archaeologists found the remains of a man in his 40s who was probably an important Cahokian ruler. The man was buried on a bed of more than 20,000 marine-shell disc beads arranged in the shape of a falcon,[15] with the bird's head appearing beneath and beside the man's head, and its wings and tail beneath his arms and legs. The falcon warrior or "birdman" is a common motif in Mississippian culture. This burial clearly had powerful iconographic significance. In addition, a cache of sophisticated, finely worked arrowheads in a variety of different styles and materials was found near the grave of this important man. Separated into four types, each from a different geographical region, the arrowheads demonstrated Cahokia's extensive trade links in North America.

Archeologists recovered more than 250 other skeletons from Mound 72. Scholars believe almost 62 percent of these were sacrificial victims, based on signs of ritual execution, method of burial, and other factors.[16] The skeletons include:

- Four young males, missing their hands and skulls.

- A mass grave of more than 50 women around 21 years old, with the bodies arranged in two layers separated by matting.

- A mass burial containing 40 men and women who appear to have been violently killed. The suggestion has been made that some of these were buried alive: "From the vertical position of some of the fingers, which appear to have been digging in the sand, it is apparent that not all of the victims were dead when they were interred - that some had been trying to pull themselves out of the mass of bodies."[17]

The relationship of these burials to the central burial is unclear. It is unlikely that they were all deposited at the same time. Wood in several parts of the mound has been radiocarbon-dated to between 950 and 1000 C.E.

Copper workshop

Excavations near Mound 34 from 2002-2010 have revealed a copper workshop. It is the only known copper workshop from the Mississippian-era. Artisans worked here to produce religious items, such as earrings of symbolic shape, probably for use at Cahokia. The area contains the remains of tree stumps likely used to hold anvil stones. Analysis of the copper found that it had been heated and annealed.[18]

Cahokia's decline

Cahokia began to decline after 1300. It was abandoned more than a century before Europeans arrived in North America in the early 1500s,[19] and the area around it was largely uninhabited by indigenous tribes.[20] Scholars have proposed environmental factors such as over-hunting and deforestation as explanations. The houses, stockade, and residential and industrial fires would have required the annual harvesting of thousands of logs. In addition, climate change could have aggravated effects of erosion due to deforestation, and adversely affected the cultivation of maize, on which the community had depended.

Another possible cause is invasion by outside peoples, though the only evidence of warfare found so far is the wooden stockade and watchtowers that enclosed Cahokia's main ceremonial precinct. Due to the lack of other evidence for warfare, the palisade appears to have been more for ritual or formal separation than for military purposes. Diseases transmitted among the large, dense urban population are another possible cause of decline. Many recent theories propose conquest-induced political collapse as the primary reason for Cahokia’s abandonment.[21]

See also

- Mississippian culture

- Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

- Mississippian stone statuary

- Monks Mound

- Sugarloaf Mound

- Chunkey

- American Bottom

- Mound builder (people)

- List of Mississippian sites

- World Heritage Site

- List of archaeoastronomical sites sorted by country

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, Illinois", US World Heritage Sites, National Park Service, accessed 13 May 2009

- ↑ Sacredland.org "Mississippian Mounds", Sacred Land Film Project

- ↑ "Cahokia Mounds". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=682&ResourceType=Site. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ↑ "United States of America - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2009-03-11. http://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/us. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ Emerson, Thomas E., Lewis, R. Barry Cahokia and the Hinterlands: Middle Mississippian Cultures of the Midwest University of Illinois Press; New edition edition (30 Jun 2000) ISBN 978-0-252-06878-2 pp.33 & 46

- ↑ Townsend, Richard F, Robert V. Sharp, Garrick Alan Bailey (2000) Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10601-7. Searchable at: [1].

- ↑ Skele, Mike (1998) "The Great Knob", Studies in Illinois Archaeology', No. 4, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, Springfield, Illinois. Page 3.

- ↑ "Monks Mound Slump Repair", Page 1

- ↑ Wittry, Warren L., "An American Woodhenge," Cranbrook Institute of Science Newsletter, Vol. 33(9), pages 102-107, 1964; reprinted in Explorations into Cahokia Archaeology, Bulletin 7, Illinois Archaeological Survey, 1969.

- ↑ Wittry, Warren L. "Discovering and Interpreting the Cahokia Woodhenges", The Wisconsin Archaeologist, Vol. 77(3/4), pages 26-35.

- ↑ Friedlander, Michael W., "The Cahokia Sun Circles", The Wisconsin Archeologist, Vol. 88(1), pages 78-90, 2007.

- ↑ Art Archives:pxartxx7clr2.jpg

- ↑ Chappell, Sally Anderson (2002) Cahokia: Mirror of the Cosmos. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-10137-1. Page 100.

- ↑ "Illinois Agriculture-Technology-Hand tools-Native American Tools". http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/agriculture/htmls/technology/hand_tools/tech_hand_na.html.

- ↑ "CAHOKIA AND THE EXCAVATION OF MOUND 72". http://www.lithiccastinglab.com/gallery-pages/2001augustmound72excavation1.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ Young & Fowler, p. 148.

- ↑ Young & Fowler, pp. 146-149.

- ↑ "Copper men: Archaeologists uncover Stone Age copper workshop near Monk's Mound", George Pawlaczyk, News-Democrat, 17 Feb 2010; accessed 6 Mar 2010

- ↑ Young & Fowler p.301

- ↑ Pyburn, K. Anne, Ungendering Civilization Routledge; 1 edition (29 Jan 2004) ISBN 978-0-415-26058-9 [2]

- ↑ Emerson 1997, Pauketat 1994.

Further reading

- Introductory Bibliography of Published Sources on Cahokia Archeology

- Scholarly Bibliography of Published Sources on Cahokia Archaeology

- Chappell, Sally A. Kitt, Cahokia: Mirror of the Cosmos, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

- Emerson, Thomas (1997). Cahokia and the Archaeology of Power. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama. ISBN 0-8173-0888-1. http://www.uapress.ua.edu/NewSearch2.cfm?id=10615.

- Emerson, Iseminger; L. Michael Nance, Madeline Winslow, and Marilyn Gass (2001). Cahokia Mounds State Historical Site Nature/Culture Hike Guidebook, 4th revised edition. Collinsville, Illinois: Cahokia Mounds Museum Society. pp. 79 pp.

- Emerson, Thomas; Barry Lewis (1991). Cahokia and the Hinterlands: Middle Mississipian Cultures of the Midwest. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois. ISBN 0-252-06878-5. http://www.press.uillinois.edu/s00/emerson.html.

- Fowler, Melvin L., Jerome Rose, Barbara Vander Leest, Steven R. Ahler. The Mound 72 Area: Dedicated and Sacred Space in Early Cahokia (1999).

- Milner, George R. (2004). The Moundbuilders: Ancient Peoples of Eastern North America. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd..

- Mink, Claudia Gellman (1992). Cahokia, City of the Sun: Prehistoric Urban Center in the American Bottom. Collinsville, IL: Cahokia Mounds Museum Society. ISBN 1-881563-00-6. http://www.powellarchaeology.org/BookCatalog/CityOfSun.html.

- Pauketat, Timothy (1994). The Ascent of Chiefs: Cahokia and Mississippian Politics in Native North America. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama. ISBN 0-8173-0728-1. http://www.uapress.ua.edu/NewSearch2.cfm.

- Pauketat, Timothy R., Cahokia: Ancient America's Great City on the Mississippi, New York, Viking Adult, 2009. ISBN 0-670-02090-7; ISBN 978-0-670-02090-4

- Price, Douglas T. and Gary M. Feinman. Images of the Past, 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008. ISBN 978-0-07-340520-9. pg. 280-285.

- Young, Biloine; Melvin L. Fowler (2000). Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois. ISBN 0-252-06821-1. http://www.press.uillinois.edu/f99/young.html. full text available at [3]

External links

- Cahokia Mounds Homepage and Map of the Site

- "Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, Illinois", World Heritage Site, National Park Service

- "Cahokia Mounds", Illinois Historic Preservation Agency

- "Cahokia Mounds"

- "Metropolitan Life on the Mississippi", Washington Post, March 12, 1997

- Mississippian Art and Artifacts

- Visitors' perspectives

- Woodhenge and the Cahokia Mounds

- Cahokia travel guide from Wikitravel

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||