Camphor

| Camphor[1][2] | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo

[2.2.1]heptan-2-one |

|

|

Other names

2-bornanone, 2-camphanone

bornan-2-one, Formosa |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 76-22-2 [464-48-2] ((1S)-Camphor} |

| PubChem | 2537 |

| ChemSpider | 2441 |

| IUPHAR ligand | 2422 |

| RTECS number | EX1260000 (R) EX1250000 (S) |

|

SMILES

O=C1CC2CCC1(C)C2(C)C

|

|

|

InChI

InChI=1/C10H16O/c1-9(2)7-4-5-10(9,3)8(11)6-7/h7H,4-6H2,1-3H3

Key: DSSYKIVIOFKYAU-UHFFFAOYAK |

|

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C10H16O |

| Molar mass | 152.23 |

| Appearance | White or colorless crystals |

| Density | 0.990 (solid) |

| Melting point |

179.75 °C (452.9 K) |

| Boiling point |

204 °C (477 K) |

| Solubility in water | 0.12 g in 100 ml |

| Solubility in chloroform | ~100 g in 100 ml |

| Chiral rotation [α]D | +44.1° |

| Hazards | |

| R-phrases | 11-20/21/22-36/37/38 |

| S-phrases | 16-26-36 |

| NFPA 704 |

2

2

0

|

| Related compounds | |

| Related Ketones | Fenchone Thujone |

| Related compounds | Camphene Pinene Borneol Isoborneol Camphorsulfonic acid |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) |

|

| Infobox references | |

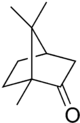

Camphor is a waxy, white or transparent solid with a strong, aromatic odor.[3] It is a terpenoid with the chemical formula C10H16O. It is found in wood of the camphor laurel (Cinnamomum camphora), a large evergreen tree found in Asia (particularly in Borneo and Taiwan) and also of Dryobalanops aromatica, a giant of the Bornean forests. It also occurs in some other related trees in the laurel family, notably Ocotea usambarensis. It can also be synthetically produced from oil of turpentine. It is used for its scent, as an ingredient in cooking (mainly in India), as an embalming fluid, in religious ceremonies and for medicinal purposes. A major source of camphor in Asia is camphor basil.

Norcamphor is a camphor derivative with the three methyl groups replaced by hydrogen.

Contents |

History

The word camphor derives from the French word camphre, itself from Medieval Latin camfora, from Arabic kafur, from Sanskrit, karpoor.[4]. Barus was the port on the western coast of the Indonesian island of Sumatra where foreign traders would call to buy camphor, hence in Malay it became kapur Barus. Camphor was known in Arabia in pre-Islamic times, as it is mentioned in the Quran 76:5 as a flavoring for drinks. In the 9th century, the Arab chemist, Al-Kindi (known as Alkindus in Europe), provided the earliest recipe for the production of camphor in his Kitab Kimiya' al-'Itr (Book of the Chemistry of Perfume). By the 13th century, it was used in recipes everywhere in the Muslim world, ranging from main dishes such as tharid, stew, and desserts[5].

Already in the 19th century, it was known that with nitric acid, camphor could be oxidized into camphoric acid. Haller and Blanc published a semisynthesis of camphor from camphoric acid, which, although demonstrating its structure, would not prove it. The first complete total synthesis for camphoric acid was published by Gustaf Komppa in 1903. Its starting materials were diethyl oxalate and 3,3-dimethylpentanoic acid, which reacted by Claisen condensation to give diketocamphoric acid. Methylation with methyl iodide and a complicated reduction procedure produced camphoric acid. William Perkin published another synthesis a short time later. Previously, some organic compounds (such as urea) had been synthesized in the laboratory as a proof of concept, but camphor was a scarce natural product with a worldwide demand. Komppa realized this and began industrial production of camphor in Tainionkoski, Finland, in 1907.

Production

Camphor can be produced from α-pinene, which is abundant in the oils of coniferous trees and can be distilled from turpentine produced as a side product of chemical pulping. With acetic acid as the solvent and with catalysis by a strong acid, α-pinene readily rearranges into camphene, which in turn undergoes Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement into the isobornyl cation, which is captured by acetate to give isobornyl acetate. Hydrolysis into isoborneol followed by dehydrogenation gives camphor.

Biosynthesis

In biosynthesis camphor is produced from geranyl pyrophosphate, via cyclisation of linaloyl pyrophosphate to bornyl pyrophosphate, followed by hydrolysis to borneol and oxidation to camphor.

Uses

Modern uses include as a plasticizer for nitrocellulose, as a moth repellent, as an antimicrobial substance, in embalming, and in fireworks. Solid camphor releases fumes that form a rust-preventative coating and is therefore stored in tool chests to protect tools against rust.[6] Camphor crystals are also used to prevent damage to insect collections by other small insects.

It is also used in medicine. Camphor is readily absorbed through the skin and produces a feeling of cooling similar to that of menthol and acts as slight local anesthetic and antimicrobial substance. There are anti-itch gels and cooling gels with camphor as the active ingredient. Camphor is an active ingredient (along with menthol) in vapor-steam products, such as Vicks VapoRub, and it is effective as a cough suppressant. It may also be administered orally in small quantities (50 mg) for minor heart symptoms and fatigue.[7]

In the 18th century, it was used by Auenbrugger in the treatment of mania[8].

Some folk remedies also state that camphor will deter snakes and other reptiles due to its strong odor. Similarly, camphor is believed to be toxic to insects and is thus sometimes used as a repellent.

Camphor is widely used in Hindu religious ceremonies. Hindus worship a holy flame by burning camphor, which forms an important part of many religious ceremonies. Camphor is used in the Mahashivratri celebrations of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and (re)creation. As a natural pitch substance, it burns cool without leaving an ash residue, which symbolizes consciousness. Of late, most temples in southern India have stopped lighting camphor in the main Sanctum Sanctorium due to heavy deposits of carbon; however, open areas do use camphor. it also acts as rubifacient used as counter irritant for inflammed joints,sprains,rheumatic and other inflammed conditions like cold it may be used as mild nasopharyngeal decongestant It is also found in clarifying masks used for skin.

Recently, carbon nanotubes were successfully synthesized using camphor in chemical vapor deposition process.[9]

Other substances deriving from trees are sometimes wrongly sold as camphor.

Culinary

In ancient and medieval Europe camphor was used as an ingredient in sweets. It was also used as a flavoring in confections resembling ice cream in China during the Tang dynasty (AD 618–907). It was used in a wide variety of both savory and sweet dishes in medieval Arabic language cookbooks, such as al–Kitab al–Ṭabikh compiled by ibn Sayyâr al-Warrâq in the 10th century[10] and An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook of the 13th Century[11]. And it appears in sweet and savory dishes in a book written in the late 15th century for the sultans of Mandu, the Ni'matnama[12].

Currently, camphor is used as a flavoring, mostly for sweets, in Asia. It is widely used in cooking, mainly for dessert dishes, in India where it is known as Kachha(raw/crude) Karpooram ("crude camphor" in Tamil:பச்சைக் கற்பூரம்), and is available in Indian grocery stores where it is labeled as "Edible Camphor".

In Hindu pujas and ceremonies, camphor is burned in a ceremonial spoon for performing aarti. This type of camphor, the processed white crystalline kind, is also sold at Indian grocery stores. However it is not suitable for cooking and is hazardous to health if eaten. Only camphor labeled "Edible Camphor" should be used for cooking.

Medicinal

Camphor is used in several cough preparations such as Vicks and Buckley's as a cough suppressant and topical analgesic.

Toxicology

In larger quantities, it is poisonous when ingested and can cause seizures, confusion, irritability, and neuromuscular hyperactivity. In extreme cases, even topical application of camphor may lead to hepatotoxicity.[13] [14] Lethal doses in adults are in the range 50–500 mg/kg (orally). Generally, 2 g causes serious toxicity and 4 g is potentially lethal.

In 1980, the United States Food and Drug Administration set a limit of 11% allowable camphor in consumer products and totally banned products labeled as camphorated oil, camphor oil, camphor liniment, and camphorated liniment (except "white camphor essential oil", which contains no significant amount of camphor). Since alternative treatments exist, medicinal use of camphor is discouraged by the FDA, except for skin-related uses, such as medicated powders, which contain only small amounts of camphor.

Reactions

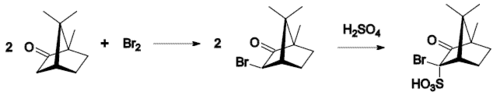

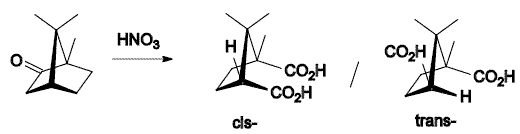

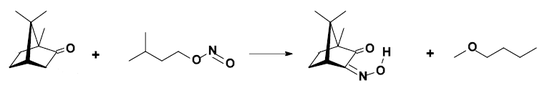

Typical camphor reactions are

- bromination,

- oxidation with nitric acid,

- conversion to isonitrosocamphor.

Camphor can also be reduced to isoborneol using sodium borohydride.

See also

- 1,4-Dichlorobenzene

- Cinnamomum camphora

- Citral

- Eucalyptol

- Lavender

- Menthol

- Vaporizer

References

- ↑ The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merk & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960

- ↑ Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- ↑ Mann JC, Hobbs JB, Banthorpe DV, Harborne JB (1994). Natural products: their chemistry and biological significance. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman Scientific & Technical. pp. 309–11. ISBN 0-582-06009-5.

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=camphor

- ↑ Anonymous Andalusian cookbook of the 13th century

- ↑ Tips for Cabinet Making Shops

- ↑ National Agency for Medicines

- ↑ Pearce, J M S (2008). "Leopold Auenbrugger: camphor-induced epilepsy - remedy for manic psychosis". Eur. Neurol. (Switzerland) 59 (1–2): 105–7. doi:10.1159/000109581. PMID 17934285.

- ↑ Kumar M, Ando Y (2007). "Carbon Nanotubes from Camphor: An Environment-Friendly Nanotechnology". J Phys Conf Ser. 61: 643–6. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/61/1/129. http://www.iop.org/EJ/abstract/1742-6596/61/1/129.

- ↑ Nasrallah, Nawal (2007). Annals of the Caliphs' Kitchens: Ibn Sayyâr al-Warrâq's Tenth-century Baghdadi Cookbook. Islamic History and Civilization, 70. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-0-415-35059-4.

- ↑ An Anonymous Andalusian cookbook of the 13th century, translated by Charles Perry

- ↑ Titley, Norah (2004). The Ni'matnama Manuscript of the Sultans of Mandu: The Sultan's Book of Delights. Routledge Studies in South Asia. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35059-4.

- ↑ Martin D, Valdez J, Boren J, Mayersohn M (Oct 2004). "Dermal absorption of camphor, menthol, and methyl salicylate in humans". J Clin Pharmacol 44 (10): 1151–7. doi:10.1177/0091270004268409. PMID 15342616.

- ↑ Uc A, Bishop WP, Sanders KD (Jun 2000). "Camphor hepatotoxicity". South Med J. 93 (6): 596–8. PMID 10881777. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0038-4348&volume=93&issue=6&spage=596.

External links

- Extensive Camphor Info (www.siu.edu)

- Camphor Evidence-based Monograph from Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database

- INCHEM at IPCS (International Programme on Chemical Safety)