Canoe

A canoe (North American English) or Canadian canoe (British English) is a small narrow boat, typically human-powered, though it may also be powered by sails or small electric or gas motors. Canoes usually are pointed at both bow and stern and are normally open on top, but can be decked over (i.e. covered, similar to a kayak).

In its human-powered form, the canoe is propelled by the use of paddles, usually by two people. Paddlers face in the direction of travel, either seated on supports in the hull, or kneeling directly upon the hull. Paddling can be contrasted with rowing, where the rowers usually face away from the direction of travel and use mounted oars (though a wide canoe can be fitted with oarlocks and rowed). Paddles may be single-bladed or double-bladed.

The oldest recovered canoe in the world is the canoe of Pesse[1] (the Netherlands).[2] According to C14 dating analysis it was constructed somewhere between 8200 and 7600 BC.[2] This canoe is exhibited in the Drents Museum in Assen, Netherlands.

Sailing canoes (see Canoe sailing) are propelled by means of a variety of sailing rigs. Common classes of modern sailing canoes include the 5 m² and the International 10 m² Sailing canoes. The latter is otherwise known as the International Canoe, and is one of the fastest and oldest competitively sailed boat classes in the western world. The log canoe of the Chesapeake Bay is in the modern sense not a canoe at all, though it evolved through the enlargement of dugout canoes.

Contents |

Design and construction

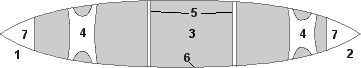

Parts

- Bow

- Stern

- Hull

- Seat (whitewater canoes may have a foam 'saddle' in place of a seat)

- Thwart - a horizontal crossbeam near the top of the hull used to increase hull strength. Often serves the secondary purpose of providing a lashing point to secure dry bags and other gear.

- Gunwale (pronounced gunnel) - the reinforcing strip running along the top edge of the hull to which the thwart(s) are attached, usually made of wood, aluminum, or polyester.

- Deck (under which a flotation compartment or foam block may be located which prevent the canoe from sinking if capsized or swamped)

Optional features in modern canoes (not shown in diagram):

- Yoke - a thwart at or near the center of the boat intended to allow one person to carry the canoe, often molded to the shape of the shoulders. The yoke is often positioned slightly ahead of the boat's centre of gravity so the bow tips slightly up when being portaged, allowing the carrier to see where they are going.

- Keel - a structural element that runs along the bottom of the canoe's hull, from the bow to the stern, serving as the foundation or spine of its structure and, depending on its depth, providing some directional control and stability.

- Flotation bags - Large inflatable air bags, usually sized to completely fill the space between 2 thwarts or a thwart and seat, and held in place by nylon netting secured to the gunwale, used to increase buoyancy and prevent swamping (by reducing the boat's internal volume) in whitewater

- Spraydeck - a cover to prevent water from entering the canoe

- Painter's ring - ring used to attach ropes

- Skid plate - piece of Kevlar glued to the bottom of the canoe for protection against abrasion from rocks and the like.

The portion of the hull between the waterline and the top of the gunwale is called the freeboard.

Materials

The earliest canoes were made from natural materials:

- Early canoes were wooden,[3] often simply hollowed-out tree trunks (see dugout). This technology is still practiced in some parts of the world. Modern wooden canoes may be wood strip (also, "stripper"), wood-and-canvas, stitch-and-glue, glued plywood lapstrake, or birchbark built by dedicated artisans. Such canoes can be very functional, lightweight, and strong, and are frequently quite beautiful works of art.

- Many indigenous peoples of the Americas built canoes of tree bark, sewn with tree roots and sealed with resin. The indigenous people of the Amazon commonly used Hymenaea trees. In temperate North America, white cedar was used for the frame and bark of the Paper Birch for the exterior, with charcoal and fats mixed into the resin. A few modern canoe builders have revived and continued building birchbark canoes, including Henri Vaillancourt, Tom MacKenzie and Marcel Labelle.

Modern technology has expanded the range of materials available for canoe construction.

- Wood-and-canvas canoes are made by fastening an external waterproofed canvas shell to a wooden hull formed with white cedar planks and ribs. These canoes evolved directly from birchbark construction. The transition occurred in the 19th century, first, when canoe builders in Ontario laid canvas instead of bark into a traditional building bed and, later, when builders in Maine adapted English boat-building inverted-forms technology. In areas where birchbark either was scarce or where demand exceeded ready supply, other materials, such as canvas, had to be used as there had been success in patching birchbark canoes with canvas or cloth. Efforts were made in various locations to improve upon the bark design such as in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, where rib-and-plank construction was used by the Peterborough Canoe Company, and in Maine, U.S.A., where similar construction was used by various companies. Maine was the location of the development of commercial wood-and-canvas canoes.

| “ | The earliest commercial builder of wood-and-canvas canoes appears to be Evan H. Gerrish of Bangor, Maine. Gerrish, a hunting and fishing guide from Brownwille, Maine, who came to Bangor in 1875 ... started experiments with a wood-and-canvas building system. ... by 1878 Gerrish was regularly producing about 18 canoes a year at his shop at 18 Broad Street. By 1882 he had hired his first employee and was building about 25 canoes a year at the average price of $25 each. The reputation of the canvas canoe was spreading to the recreational market. Gerrish already had customers far from Maine, and in 1884 he was producing over 50 canoes annually and had sent several canoes to an exhibit at the New Orleans Exposition.

Soon other companies up river from Bangor were developing their own canvas canoes and improving the manufacturing process. B.N. Morris started the Veazie Boat and Canoe Company on the second floor of his home in Veazie in 1887. It soon became the B.N. Morris Canoe Company, and for a long time it was one of the largest and best known canoe companies in the world until a fire destroyed the factory in 1920. Up river from Veazie, at Gilman Falls, E.M. White started producing canoes in 1888. In an interview in 1901 in the Old Town Enterprise, Mr. White told how he became interested in building canvas canoes. "I saw a man by the name of Evan Gerrish of Bangor riding in the Penobscot River in a canvas-covered canoe. I quickly saw the advantages of that kind over my birchbark, which moreover leaked. I examined the canvas canoe closely, and in a short time was able to produce one which was so good someone wanted to buy it." White started building canoes at his Gilman Falls family home by boiling ribs in his mother's washtub and using a horse on a treadmill for power. White's brother-in-law, E.L. Hinckley, became a working partner and provided the capital to open a large shop in nearby Old Town. The Carleton Boat and Canoe Company of Old Town built batteaux and bark canoes in the 1870s. Carleton appears to be the only one of the batteaux and/or bark builders who switched to building canvas canoes and as such was the only one who brought any previous boat building experience to the industry. Carleton was later bought by the Old Town Canoe Company in the early 1920s.[4] |

” |

In the adjoining Canadian province of New Brunswick, from the late 1800s until being disbanded in 1979, the Chestnut Canoe Company, along with the Old Town Canoe Company in Maine, became the pre-eminent producers of wood-and-canvas canoes. American President Teddy Roosevelt purchased Chestnut canoes for a South American expedition. Wood-and-canvas canoes have undergone a resurgence in recent years, spurred in part by the Wooden Canoe Heritage Association.[5] Builders abound, including Jerry Stelmok,[6] Rollin Thurlow,[7] Ken Solway,[8] Joe Seliga, and many others.[9]

- Strip-built - These are the most popular among homebuilders. Some professional builders also offered both kits and finished boats. The canoes are constructed by gluing together 1/4" x 3/4" strips of wood over a building jig consisting of station molds that define the shape of the hull. The strips may be square cut, or for a better fit, they are shaped with bead and cove router bits. Once the strips are glued together, the inside and outside are sanded fair, and a fiberglass and epoxy covering is applied to the canoe inside and out. The fiberglass covering is transparent, allowing the wood strips to be seen. The strips are usually cedar, though sometimes pine is also used. Walnut or other contrasting woods are sometimes used as accent strips.[10]

- Glued Plywood Lapstrake- These canoes are made by cutting planks to shape out of marine grade plywood. The planks are positioned on a building jig, and are glued together with epoxy at the laps along the length of the canoe. This yields a stiff hull that requires few ribs or bulkheads. The result is a traditional-looking canoe that won't leak even after long-term storage.

- Stitch and glue - Sometimes also called "tortured plywood" construction. Here, panels are cut to pattern from plywood. The panels are brought together and temporarily fastened with wire or plastic ties. During this process, the plywood is forced into the shape of a canoe dictated by the shape of the panels. The seams are then reinforced with fiberglass tape and thickened epoxy.[11]

- Aluminum canoes were first made by the Grumman company in 1944, when demand for airplanes for World War II began to drop off. Aluminum allowed a lighter and much stronger construction than contemporary wood technology. However, a capsized aluminum canoe will sink unless the ends are filled with flotation blocks. Moreover, an aluminum canoe is extremely noisy, rendering it unsuitable for viewing wildlife.

- Composites of fiberglass, Kevlar and carbon fiber are used in synthetic canoe construction. Developed over 50 years ago, these materials are light, strong, and maneuverable. Easily portaged, these canoes allow experienced paddlers access to remote wilderness areas. While Kevlar and Carbon Fiber are generally very expensive, they are usually more durable than other materials. Fiberglass retains the lightweight, but cracks easily with impact. Fiberglass is, however, very easily repaired, unlike almost all other materials.

- Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene or ABS , trademarked as "Royalex", is another synthetic composite material that makes an extremely flexible and durable hull. It is suitable, in particular, for whitewater canoes. ABS canoes have been known to pop back into their original shape with minimal creasing of the hull after having been wrapped around a rock in strong river currents. In the very unlikely event that they are punctured, they are however, very difficult to repair.

- Polyethylene is a cheaper and heavier material used for synthetic canoe construction with the benefit of superior abrasion resistance, primarily found in whitewater canoes. Ram-X and Tripletough are the trademarks for Pelican/Coleman and Mad River respectively. This material too can be difficult to repair if punctured.

Depending on the intended use of a canoe, the various kinds have different advantages. For example, a wood-and-canvas canoe is more fragile than an aluminum canoe, and thus less suitable for use in rough water; but it is much quieter — thus better for observing wildlife. However, canoes made of natural materials require regular maintenance without which they lack durability. A Kevlar canoe is tough and also light, good for wilderness tripping. Modern hybrids can combine the elegance and style of traditional wooden canoes with such benefits as modern materials can provide.

Shape

Many canoes are symmetrical about the centerline, meaning their shape can be mirrored along the center. When trimmed level (rarely the case) they should handle the same whether paddling forward or backward. Many modern designs are asymmetrical, usually having the widest beam slightly farther aft which improves efficiency and promotes more level fore and aft trim. A further improvement may be found in canoes with a straighter hull profile aft and rocker forward which improves tracking.

A traditionally shaped canoe, like a voyageur canoe, will have a tall rounded bow and stern. Although tall ends tend to catch the wind, they serve the purpose of shedding waves in rough whitewater or ocean travel.

Some canoes are made with squared sterns — "Y", "V", or "U" shaped — in order to permit the mounting of outboard motors. Very large freighter canoes can be powered with powerful motors, but canoes that are 18 feet (5.49 m) or less in length would normally be propelled by motors of 3 horsepower (2.2 kW) or less. Side brackets can be mounted on canoes with pointed sterns to mount small outboard motors of about 11⁄2 to 2 horsepower (1.1 to 1.5 kW), which propel such canoes with surprising speed.

Cross section

The shape of the hull's cross section significantly influences the canoe's stability under differing conditions. Flat-bottomed canoes generally have excellent initial stability, which diminishes rapidly with increased heel. Their high initial stability causes them to have a more abrupt motion in waves from the side.

For a given beam, a rounded-bottom canoe will have less initial stability than its flatter bottomed cousin. Round sections have lower surface area for a given volume and have less resistance through the water. They are most often associated with racing canoes.

In between the flat and rounded bottom are the more common shallow-arc and "V" bottom canoes which provide a compromise between performance and stability. The shallow-vee bottom, where the hull centerline forms a ridge like a shallow "V", will behave similar to a shallow-arc bottom but its volume to surface ratio is worse.

Similar is the tumblehome hull which has the top portion of the hull curving back in slightly.

Many modern canoes combine a variety of cross sections to suit the canoe's purpose.

Keels

Keels on canoes improve directional stability (the ability to 'track' in a straight line) but decrease the ability to turn quickly. Consequently, they are better suited for lake travel, especially when traveling on open water with crosswinds. Conversely, keels and "Vee"-bottoms are undesirable for whitewater because often quick turns are required.

In aluminum canoes, small keels occur as manufacturing artifacts when the two halves of the hull are joined. In wood-and-canvas canoes, keels are rub-strips to protect the boat from rocks and as they are pulled up on shore. Plastic canoes feature keels to stiffen the hull and allow internal tubular framing to lie flush with the sole of the canoe. Primitive replica canoes fabricated from animal pelt and other natural materials often utilize green branches and other flexible, organic material to retain a buoyant form while resisting risk of puncture or abrasion.

Rocker

Curvature of the hull profile that rises up at the bow and stern is called "rocker". Increasing the rocker improves maneuverability at the expense of tracking (the hull's tendency to travel a straight line without the need for constant course correction). Specialized canoes for whitewater play have an extreme rocker and therefore allow quick turns and tricks. Increased rocker also tends to increase the stability of a canoe; by lifting the ends of the craft out of the water, rocker puts more of the wider, center section of the boat into the water, contributing significantly to the overall stability of the craft. A 35 millimeters (1.4 in) rocker at each end suffices to make a substantial difference to how safe a novice will feel in a canoe.

Gunwales

Modern cedar-strip canoes have gunwales which consist of an inner and outer parts called "inwales" and "outwales". These two parts of the gunwale give rigidity and strength to the hull. The inwale will often have "scuppers" or slots cut into the inwale to allow water to drain when the canoe hull is turned upside down for storing.

Types

In the past, people around the world have built very different kinds of canoes, ranging from simple dugouts to large outrigger varieties. More recently, technologically advanced designs have emerged for particular sports.

Traditional designs

Early canoes have always incorporated the natural materials available to the local people. The different canoes (or canoe like) in many parts of the world were:

Dugout |

Formed of hollowed logs; may have outriggers in some cultures. On the west coast of North America, large dugout canoes were used in the Pacific Ocean, from fishing to whaling. |

|---|---|

Birch-bark canoe |

In the temperate regions of eastern North America, canoes were traditionally made of a wooden frame covered with bark of a birch tree, pitched to make it waterproof. |

Voyageur canoe |

Traditional voyageur canoes were similar to birch-bark canoes but larger and purpose built for the fur trade business, capable of carrying 12 to 20 passengers and 1,400 kilograms (3,100 lb) of cargo. |

Wood-and-canvas canoe |

The wood-and-canvas canoe evolved in Maine in the late 19th century from the birchbark canoe when canvas became much easier to acquire than the bark of the white birch tree. The canoe shown here was built by the late well-known craftsman, Joe Seliga, of Ely, Minnesota. |

War canoe |

War canoes have been extensively used in Africa to transport troops and supplies, and engage targets onshore. While documentation of canoe versus canoe battles in on the open ocean is rare, records from the 14th century mention various tribal peoples of West Africa using huge fighting canoes in inland waters, some up to 80 feet (24 m) and carrying over 100 men.[12] Construction of the war canoe was typically from one massive tree trunk, with the silk cotton tree being particularly useful. The inside was dug out and carved using fire and hand tools. Braces and stays were used to prevent excessive expansion while the fire treatment was underway. Fire also served to release sap as a preservative against insect pests. Some canoes had 7 to 8 feet (2.4 m) of width inside, accommodating benches for rowers, and facilities such as fireplaces and sleeping berths. Warriors onboard were typically armed with shield, spear and bow. In the gunpowder era, small iron or brass cannon were sometimes mounted on the bow or stern, although the firepower delivered from these areas and weapons was relatively ineffective. Musketeers delivering fire to cover raiding missions generally had better luck. The typical tactic was to maneuver close to shore, discharge weapons, then quickly pull out to open water to reload, before dashing in again to repeat the cycle. Troop and supply transport were the primary missions, but canoe versus canoe engagements in the lagoons, creeks and lakes of West Africa were also significant.[13] |

Modern designs

Modern canoe types are usually categorized by the intended use. Many modern canoe designs are hybrids (a combination of two or more designs, meant for multiple uses). The purpose of the canoe will also often determine the materials used. Most canoes are designed for either one person (solo) or two persons (tandem), but some are designed for more than two persons.

Touring and Tripping canoes. |

In North America, a "touring canoe" is a straight tracking boat good for wind blown lakes etc. A "tripping canoe" has a larger capacity for wilderness travel and is designed with more rocker for better maneuverability on whitewater rivers but requiring some skill on the part of the canoeist in open windy waters, when lightly loaded. Touring canoes are often made of lighter materials and built for comfort and cargo space; whereas Tripping canoes (such as the Chestnut Prospector derivates, and the Old Town trippers), are typically made of heavier and tougher materials, and are of course usually a more traditional design. |

|---|---|

Prospector canoe |

A generic name for copies of the famed Chestnut model, a popular type of tripping canoe marked by a symmetrical hull and a relatively large amount of rocker; giving a nice balance for wilderness tripping, of the ability to carry large amounts of gear whilst being maneuverable enough for whitewater. This makes it a superb large capacity wilderness boat, but requires skill on windy, broad waters when lightly loaded. Made in a variety of materials. For home construction, 4 mm plywood is commonly used, mainly marine ply, using the "stitch and glue" technique. Commercially built canoes are commonly built of fibreglass, HDPE, Kevlar, Carbon Fiber, and Royalex which is although relatively heavy, very durable. |

| Long Distance Touring canoe | A long-distance touring canoe is mostly covered with a greatly extended deck, forming a "cockpit" for the paddlers. A cockpit has many advantages: the gunwale can be made lower and narrower so the paddler can reach the water more easily, and the rim of the boat can be higher keeping the boat dryer. With a rounded hull shape and full ends there is less for turbulent water to work on. |

| Whitewater canoe | Also known as river canoe - typically made of tough man-made materials, such as ABS or Kevlar, for strength; no keel and increased rocker for maneuverability; often extra internal lashing points are present to secure flotation bags, harness, and spraydeck. Some canoes are decked and look very much like a kayak, but are still paddled with the paddler in a kneeling position and with a single bladed paddle. |

Playboating decked canoe |

A subgroup of whitewater canoes specialized for whitewater play and tricks. Most are identical to short, flat-bottomed kayak playboats except for internal outfitting. The paddler kneels and uses a single-blade canoe paddle. |

Whitewater slalom canoe |

Decked canoes which look very much like a kayak, but are still paddled with the paddler in a kneeling position and with a single bladed paddle. |

| Square stern canoe | An asymmetrical canoe with a squared off stern for the mounting of an outboard motor; meant for lake travel or fishing. |

Racing canoe |

Also known as sprint canoe - purpose-built racing canoe for use in racing on flat water. To reduce drag, they are built long and with a narrow beam, which makes them very unstable. A one-person sprint canoe is 5.2 meters or 17 feet (5.2 m) long. Sprint canoes are paddled kneeling on one knee, and only paddled on one side; in a C-1, the canoeist will have to j-stroke constantly to maintain a straight course. Marathon canoe races use a similar narrow boat. |

Inflatable canoe |

Similar in construction and materials to other inflatable boats but shaped like a canoe. It is meant for serious whitewater and is usually difficult to use for flat water travel. |

Outrigger canoe |

A canoe with an attached float, called an outrigger (or ama), to provide stability. Commonly used for racing. |

Differences from other paddled boats

- Kayak - A kayak differs from a canoe in that the kayak uses a double-bladed (one on each end) paddle while canoes use a single bladed (one blade at one end and a t-grip at the other) paddle, while canoes are generally open decked and kayaks are generally closed deck there are exceptions, such as wildwater canoes which are closed decked and surf kayaks which are open decked. A double-bladed paddle allows for more efficient propulsion (higher stroke rate possible, etc.), but is more difficult to use effectively in a wider craft (canoes tend to be wider than kayaks). The spraydeck (also known as a skirt) is used to seal the gap between the deck and the paddler, making it possible to recover from a capsize without flooding the interior of the hull with water. In some parts of the world kayaks are considered canoes, and open-decked canoes are called "Canadian canoes".

- Rowboat - Not considered a canoe. It is propelled by oars resting in pivots on the gunwales or on 'riggers' that extend out from the boat. A rower may use one (sweep-oar) or two oars (sculling). A rower sits with his or her back toward the direction of travel. Some rowboats, such as a McKenzie River dory or a raft outfitted with a rowing frame are suitable for whitewater.

- Adirondack guideboat - a rowboat that has similar lines to a canoe. However the rower sits closer to the bilge and uses a set of pinned oars to propel the boat.

- Dragon boat - while it handles similarly to and is paddled the same way as a large canoe, a dragon boat is not considered a canoe since its construction is markedly different.

Use

Canoes have a reputation for instability, but this is not true if they are handled properly. For example, the occupants need to keep their center of gravity as low as possible. Canoes can navigate swift-moving water with careful scouting of rapids and good communication between the paddlers.

When two people occupy a canoe, they paddle on opposite sides. For example, the person in the bow (the bowman) might hold the paddle on the port side, with the left hand just above the blade and the right hand at the top end of the paddle. The left hand acts mostly as a pivot and the right arm supplies most of the power. The sternman would paddle to starboard, with the right hand just above the blade and the left hand at the top. For travel straight ahead, they draw the paddle from bow to stern, in a straight line parallel to the gunwale.

Tandem steering

The paddling action of two paddlers will tend to turn the canoe toward the side opposite that on which the stern paddler is paddling. Thus, steering is very important, particularly because canoes have flat-bottomed hulls and are very responsive to turning actions. Steering techniques vary widely, even as to the basic question of which paddler should be responsible for steering.

Among experienced white water canoeists, the stern paddler is primarily responsible for steering the canoe, with the exception of two cases: The bow paddler will steer when avoiding rocks and other obstacles that the stern paddler cannot see. Also, in the case of back ferrying, the bow paddler is responsible for steering the canoe using small correctional strokes while back paddling with the stern paddler.

Among less-experienced canoeists, the canoe is typically steered from the bow. The advantage of steering in the bow is that the bow paddler can change sides more easily than the stern paddler. Steering in the bow is initially more intuitive than steering in the stern, because to steer to starboard, the stern paddler must actually switch to port. On the other hand, the paddler who does not steer usually produces the most forward power or thrust, and the greater source of thrust should be placed in the bow for greater steering stability.

On flat water, a turn can also be made by simply leaning the canoe towards the outside of the turn while paddling normally with a forward stroke.

Paddle strokes

Paddle strokes are important to learn if the canoe is to move through the water in a safe and effective manner. Categorizing strokes makes learning them easier. After the strokes are mastered, they can be combined or modified so that maneuvers are accomplished in an efficient, effective, and skillful manner.[14] Here are the primary strokes:

- The cruising stroke or forward stroke is the easiest stroke and is considered to be the foundation of all the other strokes. The paddle blade is brought forward along the side of the canoe, dipped into the water, and drawn back. The paddle should be drawn straight back rather than following the gunwale's curvature. In a tandem canoe, it is used mainly by the bowman to simply propel the canoe forward without turning.

- The back stroke is essentially the same movement as the forward stroke, but done in reverse. The back face of the blade is used in this case. This stroke is used to make the canoe go backward or to stop the canoe.

- The J-stroke is so named because, when done on the port side, it resembles the letter J. It begins like a standard stroke, but towards the end the paddle is rotated and pushed away from the canoe with the power face of the paddle remaining the same throughout the stroke. This conveniently counteracts the natural tendency of the canoe to steer away from the side of the stern man's paddle. Advocates of steering in the stern of tandem canoes often use this stroke, and it is also used in reverse by the bowman while backpaddling or back ferrying in white water.

- The Superior stroke is a less elegant but more effective stroke which is used in the stern of tandem canoes. It is more commonly referred to as the goon or rudder stroke. Unlike the J-stroke in which the side of the paddle pushing against the water during the stroke (the power face) is the side which is used to straighten the canoe, this stroke uses the opposite face of the paddle to make the steering motion. It is somewhat like a stroke with a small pry at the end of it. This stroke uses larger muscle groups, is preferable in rough water and is the one used in white water. It is commonly thought to be less efficient than the J-stroke when paddling long distances across relatively calm water.

- The pitch stroke is the preferred stroke to go straight in a canoe with a good traveling speed, because this stroke tries to correct the yaw caused by the forward stroke almost on the same moment that it starts, where other correction strokes do this after the forward stroke, when there already is considerable yaw from the canoe.

- The Indian stroke may be used to paddle a straight course like the J. It can be useful against strong winds or running rapids. Move the paddle forward, rotate the grip of the paddle in the palm of your upper hand. Then you are ready for the next power stroke without taking the blade out of the water. If done carefully, there is no sound from the paddle, making it possible to paddle in calm water without sound.

- The pry stroke begins with the paddle inserted vertically in the water, with the power face outward, and the shaft braced against the gunwale. A gentle prying motion is applied, forcing the canoe in the opposite direction of the paddling side.

- The push-away stroke has an identical purpose to the pry stroke, but is performed differently. Instead of bracing the paddle against the gunwale, the paddle is held vertically, as in the draw stroke, and pushed away from the hull. This is more awkward and requires more force than the pry, but has the advantage of preventing damage to the paddle and canoe due to rubbing on the gunwale. It also uses force more efficiently, since the paddle is pushing straight out, instead of up and out.

- The running pry can be applied while the canoe is moving. As in the standard pry, the paddle is turned sideways and braced against the gunwale, but rather than forcing the paddle away from the hull, the paddler simply turns it at an angle and allows the motion of the water to provide the force.

- The draw stroke exerts a force opposite to that of the pry. The paddle is inserted vertically in the water at arm's length from the gunwale, with the power face toward the canoe, and is then pulled inward to the paddler's hip. A draw can be applied while moving to create a running or hanging draw. For maximum efficiency, if multiple draw strokes are required, the paddle can be turned 90° and sliced through the water away from the boat between strokes. This prevent the paddler from having to lift the paddle out of the water and replace it for each stroke.

- The scull, also known as a sculling draw is a more efficient and effective stroke where multiple draw strokes are required. Instead of performing repeated draw strokes, the paddle is "sculled" back and forth through the water. Beginning slightly in front of the paddler, the paddle is angled so that the power face points at a 45° angle toward the hull and astern. The paddle is drawn straight backward, maintaining the angle, and then the angle is rotated so that the power face is pointing 45° toward the hull and the bow. The paddle is pushed straight forward, and the whole process is repeated. The net effect is that the paddler's end of the canoe is drawn toward the paddling side.

- The reverse scull (sometimes sculling pry or sculling push-away) is the opposite of the scull. The stroke is identical, but with the paddle angles reversed. The net effect is that the paddler's end of the canoe is pushed away from the paddling side.

- The cross-draw stroke or cross-bow draw is a stroke that exerts the same vector of force as a pry, by moving the blade of the paddle to the other side of the canoe without moving the paddler's hands. The arm of bottom hand crosses in front of the bowman's body to insert the paddle in the water on the opposite side of the canoe some distance from the gunwale, facing towards the canoe, and is then pulled inward while the top hand pushes outward. The cross-draw is much stronger than the draw stroke, but normally can't be used by the stern paddler in a tandem canoe.

- The sweep is unique in that it steers the canoe away from the paddle regardless of which end of the canoe it is performed in. The paddle is inserted in the water some distance from the gunwale, facing forward, and is drawn backward in a wide sweeping motion. The paddler's bottom hand is choked up to extend the reach of the paddle. In the case of the bowman, the blade will pull a quarter-circle from the bow to the paddler's waist. If in the stern, the paddler pulls from the waist to the stern of the canoe. Backsweeps are the same stroke done in reverse.

- The C-stroke is used in both solo and tandem paddling. It is generally used to turn the canoe to the side opposite of the sterner. With only one paddler, doing a simple bow stroke will cause the canoe to turn rapidly away from the paddling side. To counteract this, the paddler draws toward the boat, paddles forward as in a normal stroke, and pushes away as in a j-stroke. This is opposite to a sweep. It serves the same purpose as a J-stroke (counteracting the natural turn of the canoe away from the paddling side), but provides more correction which is necessary when starting a solo canoe from a standstill or paddling in strong wind or current. When tandem paddling, the C-stroke is generally used in the stern only. To turn the boat to the side opposite of the sterner, the sterner moves the paddle in a "C" shape, by paddling in an ark, whose apex points away from the boat. In tandem canoes, complementary strokes are selected by the bow and stern paddlers in order to quickly and sharply steer the canoe. It is important that the paddlers remain in unison, particularly in white water, in order to keep the boat stable and to maximize efficiency.

There are some differences in techniques in how the above strokes are utilized.

- One of these techniques involves locking or nearly locking the elbow, that is on the side of the canoe the paddle is, to minimize muscular usage of that arm to increase endurance. Another benefit of this technique is that along with using less muscle you gain longer strokes which results in an increase of the power to stroke ratio. This is generally used more with the 'stay on one side' method of paddling.

- The other technique is generally what newer canoeists use and that is where they bend the elbow to pull the paddle out of the water before they have finished the stroke. This is generally used more with the 'switch sides often' method of paddling.

- The stay on one side method is where each canoeist takes opposite sides and the stern man uses occasional J-strokes to correct direction of travel. The side chosen is usually the paddlers' stronger side, since this is more comfortable and less tiring. Some canoeists do, however, switch sides after twenty to thirty minutes or longer as a means of lessening muscle fatigue.

- The switch sides often method (also called hit and switch, hut stroke, or Minnesota switch) allows the canoeists to switch sides frequently (usually every 5 to 10 strokes, on a vocal signal, commonly "hut") to maintain their heading. This method is the fastest one on flat water and is used by all marathon canoeists in the US and Canada. The method works well with bent-shaft paddles. Racer/designer Eugene Jensen is credited with the development of both "hit and switch" paddling and the bent shaft paddle .

Setting poles

On swift rivers, the stern canoeist may use a setting pole. It allows the canoe to move through water too shallow for a paddle to create thrust, or against a current too quick for the paddlers to make headway. With skillful use of eddies, a setting pole can propel a canoe even against moderate (class III) rapids.

Gunwale bobbing

A trick called "gunwale bobbing" or "gunwaling" allows a canoe to be propelled without a paddle. The canoeist stands on the gunwales, near the bow or the stern, and squats up and down to make the canoe rock backward and forward. This propulsion method is inefficient and unstable; additionally, standing on the gunwales can be dangerous. However, this can be turned into a game where two people stand one on each end, and attempt to cause the other to lose balance and fall into the water, while remaining standing themselves.

Notable Canoeists

The following persons have made historically significant or remarkable canoe expeditions:[15]

Traditional

- Samuel de Champlain - the first European to explore Canada's interior, canoeing as far as the Georgian Bay in 1615

- Alexander Mackenzie - the first explorer to cross the North American continent, reaching the Arctic in 1789 and the Pacific in 1793

- Meriwether Lewis and William Clark - the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804 was the first U.S. expedition to the Pacific coast and back

- David Thompson - explorer and geographer who travelled 80,000 miles (129,000 km) and mapped over 1,500,000 square miles (3,900,000 km2) of North America

- John MacGregor - credited with the development of the first sailing canoes and with popularising canoeing as a middle class sport in Europe and the United States

- Bill Mason - Canadian naturalist, author, artist, filmmaker, and conservationist, noted primarily for his popular canoeing books, films, and art

Modern - Distance

- Verlen Kruger - marathon canoeist having paddled nearly 100,000 miles (160,000 km), including 2 trips over 20,000 miles (32,000 km)

- Don Starkell - paddled a distance of 12,181 miles (19,603 km) from Winnipeg to Belém, Brazil

- Gary and Joanie McGuffin - paddled across Canada on their honeymoon, circumnavigated Lake Superior, and canoed 1,200 miles (1,900 km) through 12 previously unconnected watersheds of northern Ontario

- Ian and Sally Wilson - followed 1,200 miles (1,900 km) of fur trade routes from Lake Superior to northern Saskatchewan while using authentic Voyageur methods and gear

- Todd Foster, Scott Miller and Matt Lutz - followed famed CBS reporter Eric Sevaried's 1935 route from Minneapolis to Hudson Bay, a distance of over 2250 miles.

Image gallery

Spearing Salmon By Torchlight, an oil painting by Paul Kane |

Canoe Manned by Voyageurs Passing a Waterfall (Ontario), oil painting by Frances Anne Hopkins |

Ojibwe women in canoe on Leech Lake |

A dugout canoe of pirogue type in the Solomon Islands |

Antique Strip-built Canoes at the Adirondack Museum |

Aluminum canoe, Upper Klamath Lake |

Canoeing on the Shenandoah River, Winchester, Virginia |

Canoes stored at Lake Harriet Minneapolis, Minnesota |

See also

|

References

Notes

- ↑ Van Zeist, W. (1957), "De steentijd van Nederland", Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak 75: 4–11

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Mysterious Bog People - Background to the exhibition". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. 2001-07-05. http://www.civilization.ca/media/docs/pr148beng.html. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ What is a Wood Canoe?

- ↑ The Wood and Canvas Canoe, by Jerry Stelmok and Rollin Thurlow, pp. 24-25, Harpswell Press, Gardiner, Maine, 1987, ISBN 0-88448-046-1

- ↑ Wooden Canoe Heritage Association

- ↑ Island Falls Canoe Co.

- ↑ Northwoods Canoes

- ↑ Chestnut Canoe

- ↑ WCHA Directory of Builders & Suppliers

- ↑ How to build a cedar strip canoe

- ↑ Assembling a Boat Kit: Stitch & Glue Construction

- ↑ Robert Smith, The Canoe in West African History, The Journal of African History, Vol. 11, No. 4 (1970), pp. 515-533

- ↑ Law, op. cit

- ↑ American National Red Cross. Canoeing. 1985. p. 135. ISBN 0-385-08313

- ↑ Matthew Jackson (May 2002). "The World's Top Canoe Expeditions". Paddler Magazine. http://www.paddlermagazine.com/issues/2002_3/article_181.shtml. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

Further reading

- The Canoe, Its Selection, Care, and Use, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1914, by Robert E. Pinkerton

- The Bark Cannoes and Skin Boats of North America, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 1983, by Edwin Tappan Adney and Howard I. Chapelle

- Pole, Paddle, & Portage, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 1969, by Bill Riviere

- The Complete Wilderness Paddler, ISBN 0-394-49347-8, by James West Davidson and Jon Rugge

- North American Canoe Country, Macmillan Company, Toronto, 1964, by Calvin Rutstrum

- Building the Maine Guide Canoe, ISBN 0-87742-120-X, by Jerry Stelmok

- The Wood & Canvas Canoe, ISBN 0-88448-046-1, by Jerry Stelmok and Rollin Thurlow

- The Survival of the Bark Canoe ISBN 0-374-27207-7, by John McPhee

- Path of the Paddle ISBN 1-55209-328-X, by Bill Mason

- Song of the Paddle ISBN 1-55209-089-2, by Bill Mason

- Thrill of the Paddle ISBN 1-55209-451-0, by Paul Mason

- Canoecraft: An Illustrated Guide to Fine Woodstrip Construction ISBN 1-55209-342-5, by Ted Moores

External links

- About.com Paddling: Technique, Safety, Photos, and Gear Reviews

- Canoe Sailing Magazine

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization - Native Watercraft in Canada

- International Canoe Federation Homepage

- Canadian Canoe Museum

- History of Canoes in Canada

- Wooden Canoe Heritage Association

- Wisconsin Canoe Heritage Museum

- Canoeing.com: Canoe Design

- Paddling graphics

- An article about Canoeing from The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Watch a documentary on how to build a bark canoe

- Excavating Stone Age site Tybrind Vig, Denmark: Dugouts and Paddles

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||