Crochet

Crochet (pronounced /kroʊˈʃeɪ/) is a process of creating fabric from yarn or thread using a crochet hook. The word is derived from the French word "crochet", meaning hook. Crocheting, similar to knitting, consists of pulling loops of yarn through other loops. Crochet differs from knitting in that only one loop is active at one time (the sole exception being Tunisian crochet), and that a crochet hook is used instead of knitting needles.

Contents |

History

Origins

Some theorize that crochet evolved from traditional practices in Arabia, South America, or China, but there is no decisive evidence of the craft being performed before its popularity in Europe during the 1800s. The earliest written reference to crochet refers to shepherd's knitting from The Memoirs of a Highland Lady by Elizabeth Grant in 1812. The first published crochet patterns appeared in the Dutch magazine Pénélopé in 1824. Other indicators that crochet was new in the 19th century include the 1847 publication A Winter's Gift, which provides detailed instructions for performing crochet stitches in its instructions although it presumes that readers understand the basics of other needlecrafts. Early references to the craft in Godey's Lady's Book in 1846 and 1847 refer to crotchet before the spelling standardized in 1848.[1] Some speculate that crochet was in fact used by early cultures but that a bent forefinger was used in place of a fashioned hook; therefore, there were no artifacts left behind to attest to the practice. These writers point to the "simplicity" of the technique and claim that it "must" have been early.

Other writers point out that woven, knit and knotted textiles survive from very early periods, but that there are no surviving samples of crocheted fabric in any ethnological collection, or archeological source prior to 1800. These writers point to the tambour hooks used in tambour embroidery in France in the eighteenth century, and contend that the hooking of loops through fine fabric in tambour work evolved into "crochet in the air." Most samples of early work claimed to be crochet turn out to actually be samples of nålebinding. Donna Kooler identifies a problem with the tambour hypothesis: period tambour hooks that survive in modern collections cannot produce crochet because the integral wing nut necessary for tambour work interferes with attempts at crochet.[2] Kooler proposes that early industrialization is key to the development of crochet. Machine spun cotton thread became widely available and inexpensive in Europe and North America after the invention of the cotton gin and the spinning jenny, displacing hand spun linen for many uses. Crochet technique consumes more thread than comparable textile production methods and cotton is well suited to crochet.[3]

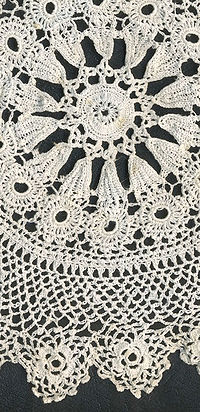

Beginning in the 1800s in Britain, America and France, crochet began to be used as a less costly substitute for other forms of lace. The price of manufactured cotton thread was dropping, and even though crocheted laces took up more thread than woven bobbin laces, the crocheted laces were faster to make and easier to teach. It's believed that some lace manufacturers paid so little that their workers resorted to prostitution.[4]

During the Great Irish Famine (1845-1849), Ursuline nuns taught local women and children to thread crochet. It was shipped all across Europe and America and purchased for its beauty and also for the charitable help it provided for the Irish population.

Hooks ranged from primitive bent needles in a cork handle, used by poor Irish lace workers, to expensively crafted silver, brass, steel, ivory and bone hooks set into a variety of handles, some of which were better designed to show off a lady's hands than they were to work with thread. By the early 1840s, instructions for crochet were being published in England, particularly by Eleanor Riego de la Branchardiere and Frances Lambert. These early patterns called for cotton and linen thread for lace, and wool yarn for clothing, often in vivid color combinations.

Early history

Around the world, crochet became a thriving cottage industry, particularly in Ireland and northern France, supporting communities whose traditional livelihoods had been damaged by wars, changes in farming and land use, and crop failures. Women and sometimes even children would stay at home and create things such as clothes and blankets to make money. The finished items were purchased mainly by the emerging middle class. The introduction of crochet as an imitation of a status symbol, rather than a unique craft in its own right, had stigmatized the practice as common. Those who could afford lace made by older and more expensive methods disdained crochet as a cheap copy. This impression was partially mitigated by Queen Victoria, who conspicuously purchased Irish-made crochet lace and even learned to crochet herself. Irish crochet lace was further promoted by Mlle. Riego de la Branchardiere around 1842 who published patterns and instructions for reproducing bobbin lace and needle lace via crochet, along with many publications for making crocheted clothing from wool yarns. The patterns available as early as the 1840s were varied and complex.

Modern practice

Fashions in crochet changed with the end of the Victorian era in the 1890s. Crocheted laces in the new Edwardian era, peaking between 1910 and 1920, became even more elaborate in texture and complicated stitching.

The strong Victorian colours disappeared, though, and new publications called for white or pale threads, except for fancy purses, which were often crocheted of brightly colored silk and elaborately beaded. After World War I, far fewer crochet patterns were published, and most of them were simplified versions of the early 20th century patterns. After World War II, from the late 40s until the early 60s, there was a resurgence in interest in home crafts, particularly in the United States, with many new and imaginative crochet designs published for colorful doilies, potholders, and other home items, along with updates of earlier publications. These patterns called for thicker threads and yarns than in earlier patterns and included wonderful variegated colors. The craft remained primarily a homemaker's art until the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the new generation picked up on crochet and popularized granny squares, a motif worked in the round and incorporating bright colors. Although crochet underwent a subsequent decline in popularity, the early 21st century has seen a revival of interest in handcrafts and DIY, as well as great strides in improvement of the quality and varieties of yarn. There are many more new pattern books with modern patterns being printed, and most yarn stores now offer crochet lessons in addition to the traditional knitting lessons. Filet crochet, Tunisian crochet, broomstick lace, hairpin lace, cro-hooking, and Irish crochet are all variants of the basic crochet method.

Crochet patterns have an underlying mathematical structure and have been used to illustrate shapes in hyperbolic geometry that are difficult to reproduce using other media or are difficult to understand when viewed two-dimensionally.[5]

Materials

Hook

The Crochet hook comes in many sizes. Steel crochet hooks range from 0.4 to 3.5 millimeters in the size of the hook, or from 00 to 16 in American sizing. These hooks are used for fine crochet work.

Aluminum, bamboo, and plastic crochet hooks are available from 2.5 to 19 millimeters in hook size, or from B to S in American sizing.

There are also many artisan-made hooks, most of hand-turned wood, sometimes decorated with semi-precious stones or beads.

Crochet hooks used for Tunisian crochet are elongated and have a stopper at the end of the handle, while double-ended crochet hooks have a hook on both ends of the handle. There is also a double hooked apparatus called a Cro-hook that has become popular.

For crocheting you will also need some type of material that will be crocheted, which is most commonly yarn or thread.

Other materials include cardboard cut-outs, which can be used to make tassels, fringe, and many other items; a pompon circle, used to make pompons; a tape measure, used for measuring crocheted work; a row counter; and occasionally plastic rings, which are used for special projects.

Yarn

Yarn for crochet is usually sold as balls or skeins (hanks), although it may also be wound on spools or cones. Skeins and balls are generally sold with a yarn-band, a label that describes the yarn's weight, length, dye lot, fiber content, washing instructions, suggested needle size, likely gauge, etc. It is common practice to save the yarn band for future reference, especially if additional skeins must be purchased. Crocheters generally ensure that the yarn for a project comes from a single dye lot. The dye lot specifies a group of skeins that were dyed together and thus have precisely the same color; skeins from different dye-lots, even if very similar in color, are usually slightly different and may produce a visible stripe when crocheted together. If insufficient yarn of a single dye lot is bought to complete a project, additional skeins of the same dye lot can sometimes be obtained from other yarn stores or online.

The thickness or weight of the yarn is a significant factor in determining the gauge, i.e., how many stitches and rows are required to cover a given area for a given stitch pattern. Thicker yarns generally require thicker crocheting hooks, whereas thinner yarns may be knit with thick or thin needles. Hence, thicker yarns generally require fewer stitches, and therefore less time, to knit up a given garment. Patterns and motifs are coarser with thicker yarns; thicker yarns produce bold visual effects, whereas thinner yarns are best for refined patterns. Yarns are grouped by thickness into six categories: superfine, fine, light, medium, bulky and superbulky; quantitatively, thickness is measured by the number of wraps per inch (WPI). The related weight per unit length is usually measured in tex or dernier.

Before use, one would typically transform a hank into a ball where the yarn emerges from the center of the ball; this making the work easier by preventing the yarn from becoming easily tangled. This transformation may be done by hand, or with a device known as a ballwinder.

A yarn's usefulness is judged by several factors, such as its loft (its ability to trap air), its resilience (elasticity under tension), its washability and colorfastness, its hand (its feel, particularly softness vs. scratchiness), its durability against abrasion, its resistance to pilling, its hairiness (fuzziness), its tendency to twist or untwist, its overall weight and drape, its blocking and felting qualities, its comfort (breathability, moisture absorption, wicking properties) and of course its look, which includes its color, sheen, smoothness and ornamental features. Other factors include allergenicity; speed of drying; resistance to chemicals, moths, and mildew; melting point and flammability; retention of static electricity; and the propensity to become stained and to accept dyes. Different factors may be more significant than others for different projects, so there is no one "best" yarn. The resilience and propensity to (un)twist are general properties that affect the ease to work with.

Although crochet may be done with ribbons, metal wire or more exotic filaments, most yarns are made by spinning fibers. In spinning, the fibers are twisted so that the yarn resists breaking under tension; the twisting may be done in either direction, resulting in an Z-twist or S-twist yarn. If the fibers are first aligned by combing them, the yarn is smoother and called a worsted; by contrast, if the fibers are carded but not combed, the yarn is fuzzier and called woolen-spun. The fibers making up a yarn may be continuous filament fibers such as silk and many synthetics, or they may be staples (fibers of an average length, typically a few inches); naturally filament fibers are sometimes cut up into staples before spinning. The strength of the spun yarn against breaking is determined by the amount of twist, the length of the fibers and the thickness of the yarn. In general, yarns become stronger with more twist (also called worst), longer fibers and thicker yarns (more fibers); for example, thinner yarns require more twist than do thicker yarns to resist breaking under tension. The thickness of the yarn may vary along its length; a slub is a much thicker section in which a mass of fibers is incorporated into the yarn.

The spun fibers are generally divided into animal fibers, plant and synthetic fibers. These fiber types are chemically different, corresponding to proteins, carbohydrates and synthetic polymers, respectively. Animal fibers include silk, but generally are long hairs of animals such as sheep (wool), goat (angora, or cashmere goat), rabbit (angora), llama, alpaca, dog, cat, camel, yak, and muskox (qiviut). Plants used for fibers include cotton, flax (for linen), bamboo, ramie, hemp, jute, nettle, raffia, yucca, coconut husk, banana trees, soy and corn. Rayon and acetate fibers are also produced from cellulose mainly derived from trees. Common synthetic fibers include acrylics,[6] polyesters such as dacron and ingeo, nylon and other polyamides, and olefins such as polypropylene. Of these types, wool is generally favored for crochet, chiefly owing to its superior elasticity, warmth and (sometimes) felting; however, wool is generally less convenient to clean and some people are allergic to it. It is also common to blend different fibers in the yarn, e.g., 85% alpaca and 15% silk. Even within a type of fiber, there can be great variety in the length and thickness of the fibers; for example, Merino wool and Egyptian cotton are favored because they produce exceptionally long, thin (fine) fibers for their type.

A single spun yarn may be crochet as is, or braided or plied with another. In plying, two or more yarns are spun together, almost always in the opposite sense from which they were spun individually; for example, two Z-twist yarns are usually plied with an S-twist. The opposing twist relieves some of the yarns' tendency to curl up and produces a thicker, balanced yarn. Plied yarns may themselves be plied together, producing cabled yarns or multi-stranded yarns. Sometimes, the yarns being plied are fed at different rates, so that one yarn loops around the other, as in bouclé. The single yarns may be dyed separately before plying, or afterwords to give the yarn a uniform look.

The dyeing of yarns is a complex art. Yarns need not be dyed; or they may be dyed one color, or a great variety of colors. Dyeing may be done industrially, by hand or even hand-painted onto the yarn. A great variety of synthetic dyes have been developed since the synthesis of indigo dye in the mid-19th century; however, natural dyes are also possible, although they are generally less brilliant. The color-scheme of a yarn is sometimes called its colorway. Variegated yarns can produce interesting visual effects, such as diagonal stripes; conversely.

Process

Crocheted fabric is begun by placing a slip-knot loop on the hook, pulling another loop through the first loop, and repeating this process to create a chain of a suitable length. The chain is either turned and worked in rows, or joined to the beginning of the row with a slip stitch and worked in rounds. Rounds can also be created by working many stitches into a single loop. Stitches are made by pulling one or more loops through each loop of the chain. At any one time at the end of a stitch, there is only one loop left on the hook. Tunisian crochet, however, draws all of the loops for an entire row onto a long hook before working them off one at a time.

International crochet terms and notations

In the English-speaking crochet world, basic stitches have different names that vary by country. The differences are usually referred to as UK/US or British/American. To help counter confusion when reading patterns, a diagramming system using a standard international notation has come into use (illustration, right).

Another terminological difference is known as tension (UK) and gauge (U.S.). Individual crocheters work yarn with a loose or a tight hold and, if unmeasured, these differences can lead to significant size changes in finished garments that have the same number of stitches. In order to control for this inconsistency, printed crochet instructions include a standard for the number of stitches across a standard swatch of fabric. An individual crocheter begins work by producing a test swatch and compensating for any discrepancy by changing to a smaller or larger hook. North Americans call this gauge, referring to the end result of these adjustments; British crocheters speak of tension, which refers to the crafter's grip on the yarn while producing stitches.

Differences from knitting

One of the more obvious differences is that crochet uses one hook while most knitting uses two needles. This is because in crochet, the artisan usually has only one live stitch on the hook, while a knitter keeps an entire row of stitches active simultaneously. So dropped stitches, which can unravel a fabric, rarely interfere with crochet work. This is also because of a second, perhaps less obvious, structural difference between knitting and crochet. In knitting, each stitch is supported by the corresponding stitch in the row above and it supports the corresponding stitch in the row below. In crochet each stitch is only supported by and supports the stitches on either side of it. If a stitch in a finished item breaks, the stitches above and below remain intact, and, because of the complex looping of each stitch, the stitches on either side are not likely to come loose unless put under a lot of stress.

Round or cylindrical patterns are simple to produce with a regular crochet hook, but cylindrical knitting requires either a set of circular needles or four or five special double-ended needles. And free form crochet can create interesting shapes in several dimensions because new stitches can be made independently of previous stitches almost anywhere in the crocheted piece.

Knitting can be accomplished by machine, while many crochet stitches can only be crafted by hand. Although some crochet patterns can emulate the appearance of knitting, distinctive crochet patterns such as the Granny square cannot be simulated by other methods.

Crochet is more suitable than knitting for joining pieces of fabric and knit patterns for sweaters may incorporate crochet for finishing. Crochet can add borders or surface embellishment to both knit and crochet fabric. Crocheted fabric uses 1/3 more yarn than knitted fabric. Crochet produces a thicker fabric than knitting, and tends to have less "give" than knitted fabric. And, generally speaking, crochet technique produces fabric faster than knitting.

Most crochet uses one hook and works upon one stitch at a time. Crochet may be worked in circular rounds without any specialized tools, as shown here. |

Knitting uses two or more straight needles that carry multiple stitches. |

Unlike crochet, knitting requires specialized needles to create circular rounds. |

Charity

It has been very common for people and groups to crochet clothing and other garments and then donate them to soldiers during war. People have also crocheted clothing and then donated it to hospitals, for sick patients and also for newborn babies. Sometimes groups will crochet for a specific charity purpose, such as crocheting for homeless shelters, nursing homes, etc.

Mathematics

Crochet has been used by mathematician Daina Taimina in order to create a version of the hyperbolic plane. A paper model based on the pseudosphere was created by William Thurston, however, it was quite delicate. Daina Taimina used the art of crochet to create a strong, durable model, which received an exhibition by the Institute For Figuring.[5]

Graffiti

In the past few years, a practice called yarn bombing, or the use of knitted or crocheted cloth to modify and beautify one's (usually outdoor) surroundings, emerged in the U.S. and spread worldwide.[7] Yarn bombers sometimes target existing pieces of graffiti for beautification.

References

- Feldman, Annette. Handmade Lace & Patterns

- Hadley, Sara. "Irish Crochet Lace", The Lace Maker, Vol. 4 3, New York: D.S. Bennet, 1911.

- Kooler, Donna. A Dictionary of Crochet

- Lambert, Miss [Frances]. My Crochet Sampler, London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1844.

- Paludan, Lis. Crochet: History & Technique

- Potter, Annie Louise. A living mystery: the international art & history of crochet

- Riego de la Branchardiere, Eléanor. Crochet Book 4th Series, London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1848.

- Riego de la Branchardiere, Eléanor. Crochet Book 6th Series, containing D'Oyleys and Anti-Macassars, London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1877. This is the 20th printing of this book; the original publishing date is probably about 1850.

- Riego de la Branchardiere, Eléanor. Crochet Book, 9th Series or Third Winter Book, London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co., 1850.

- Warren, The Court Crochet Doyley Book, London: Ackermann & Co, 1847.

- Wildman, Emily. Step-By-Step Crochet, 1972

- ↑ Donna Kooler's Encyclopedia of Crochet by Donna Kooler, Leisure Arts, Inc., Little Rock, Arkansas, pp. 10-11.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 12.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Industry & Consumerism Case 5 Labels

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Hyperbolic Space". The Institute for Figuring. December 21, 2006. http://www.theiff.org/oexhibits/oe1e.html. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ↑ Masson, James (1995). Acrylic Fiber Technology and Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.. p. 172. ISBN 0-8247-8977-6.

- ↑ Anonymous (2009-01-21). "Knitters turn to graffiti artists with 'yarnbombing'" (in English, U.K.). The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/4305406/Knitters-turn-to-graffiti-artists-with-yarnbombing.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

External links

- How to Crochet Basic tutorials to get started crocheting

- Yarn Weight Yarn weight to crochet hook size guide

- The Antique Pattern Library

- Virtual Museum of Textile Arts Ancient Crochet Lace

- Crochet at the Open Directory Project

- Crochet Work

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||