Elm

| Elm | |

|---|---|

|

|

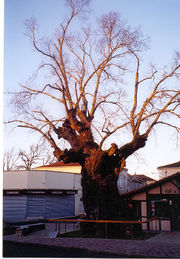

| Ulmus minor subsp. minor, East Coker, Somerset | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Ulmaceae |

| Genus: | Ulmus L. |

| Species | |

|

See

|

|

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus Ulmus, family Ulmaceae. Elms first appeared in the Miocene period about 40 million years ago. Originating in what is now central Asia, the tree flourished and established itself over most of the Northern Hemisphere, traversing the Equator in Indonesia. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many species and cultivars were planted as ornamentals in Europe, North America, and parts of the Southern Hemisphere, notably Australasia.

Elm leaves are alternate, with simple, single- or, most commonly, doubly serrate margins, usually asymmetric at the base and acuminate at the apex. The genus is hermaphroditic, having perfect flowers which, being wind-pollinated, are apetalous. The fruit is a round wind-dispersed samara. All species are tolerant of a wide range of soils and pH levels but, with few exceptions, demand good drainage.

The other genera of the Ulmaceae are Zelkova (Zelkova) and Planera (Water Elm). Celtis (Hackberry or Nettle Tree), formerly included in the Ulmaceae, is now included in the family Cannabaceae.

Contents |

Species, varieties and hybrids

There are approximately 30 to 40 species of elm; the ambiguity in number is a result of difficulty in delineating species, owing to the ease of hybridization between them and the development of local seed-sterile vegetatively propagated microspecies in some areas, mainly in the field elm group. Rackham[1] describes Ulmus as the most difficult critical genus in the entire British flora. Eight species are endemic to North America, and a smaller number to Europe;[2] the greatest diversity is found in China.[3]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, elm cultivars enjoyed much popularity as ornamentals in Europe by virtue of their rapid growth and variety of foliage and forms.[4] This 'belle époque' lasted until the First World War, when the consequences of hostilities, notably in Germany whence at least 40 cultivars originated, and the outbreak of Dutch elm disease saw the elm slide into horticultural decline. The devastation caused by the Second World War, and the demise in 1944 of the huge Späth nursery in Berlin, only accelerated the process. The outbreak of the new, three times more virulent, strain of Dutch elm disease Ophiostoma novo-ulmi in the late 1960s brought the tree to its nadir.

Since circa 1990 however, the elm has enjoyed a slow renaissance through the successful development in North America and Europe (notably the Netherlands until 1992, and, more recently, Italy) of cultivars highly resistant to the new disease.[5] Consequently, the total number of named cultivars, ancient and modern, now exceeds 300, although many of the older clones, possibly over 120, have been lost to cultivation. Unhappily, enthusiasm for the newer clones often remains low owing to the poor performance of earlier, supposedly disease-resistant Dutch trees released in the 1960s and 1970s. In the Netherlands, sales of elm cultivars slumped from over 56,000 in 1989 to just 6,800 in 2004,[6] whilst in the UK, only four of the new American and European releases were commercially available in 2008.

In 1997, a European Union elm project was initiated, its aim to coordinate the conservation of all the elm genetic resources of the member states and, among other things, to assess their resistance to Dutch elm disease. Accordingly, over 300 clones were selected and propagated for testing.[7][8][9]

The classification adopted for Elm species, varieties, cultivars and hybrids is largely based on that established by Brummitt.[10] A large number of synonyms have accumulated over the last three centuries, their Accepted Names can be found on Elm Synonyms and Accepted Names.

Cultivation and uses

Carpentry

Elm wood was valued for its interlocking grain, and consequent resistance to splitting, with significant uses in wheels, chair seats and coffins. The density of the wood varies due to differences between species, but averages around 560kg per cubic metre[11].

Engineering

The wood is also resistant to decay when permanently wet, and hollowed trunks were widely used as water pipes during the medieval period in Europe. Elm was also used as piers in the construction of the original London Bridge. However this resistance to decay in water does not extend to ground contact[12].

Livestock farming

Elms also have a long history of cultivation for fodder, with the leafy branches cut for livestock. The practice continues today in the Himalaya, where it is contributes to serious deforestation.

Food

Elm bark, cut into strips and boiled, sustained much of the rural population of Norway during the great famine of 1812. The seeds are particularly nutritious, comprising 45% crude protein, and < 7% fibre by dry mass. [13]

Landscape

From the 18th century to the early 20th century, elms were among the most widely planted ornamental trees in both Europe and North America. They were particularly popular as a street tree in avenue plantings in towns and cities, creating high-tunnelled effects. Their tolerance of air-pollution and the comparatively rapid decomposition of their leaf-litter in the fall were further advantages. In North America the species most commonly planted was the American Elm Ulmus americana, which had unique properties that made it ideal for such use: rapid growth, adaptation to a broad range of climates and soils, strong wood, resistance to wind damage, and vase-like growth habit requiring minimal pruning; In Europe, the Wych Elm U. glabra and the Smooth-leaved Elm U. minor var. minor were the most widely planted in the countryside, with the former in northern areas (Scandinavia, northern Britain), and the latter further south. The hybrid between these two, Dutch Elm U. × hollandica, occurs naturally and was also commonly planted. In England, it was the English Elm Ulmus procera which came to dominate the landscape. Most commonly planted in hedgerows, the English Elm sometimes occurred in densities of over 1000 per square kilometre; indeed such was its ubiquity it almost always featured in the landscape paintings of John Constable. In Australia, large numbers of English Elms, as well as other species and cultivars, were planted as ornamentals following their introduction in the 19th century. In parks and gardens, from about 1850 to 1920 the most prized small ornamental elm was the Camperdown Elm, Ulmus glabra 'Camperdownii', a contorted weeping cultivar of the Wych Elm grafted on a standard elm trunk to give a wide, spreading and weeping fountain shape in large garden spaces.

Biomass

As fossil fuel resources diminish, increasing attention is being paid to trees as sources of energy. In Italy, the Istituto per la Protezione delle Piante is (2010) in the process of releasing to commerce very fast growing elm cultivars, able to increase in height by > 2 m per annum but devoid of any aesthetic merit [14].

Pests and diseases

Many species of Lepidopteran larvae (butterflies and moths) use elm as a food plant; see list of Lepidoptera that feed on elms. In Australia, introduced elm trees are sometimes used as foodplants by the larvae of hepialid moths of the genus Aenetus. These burrow horizontally into the trunk then vertically down.

Dutch elm disease

Dutch elm disease devastated elms throughout Europe and North America in the second half of the 20th century. It is caused by a micro-fungus transmitted by two species of Scolytus elm-bark beetle which act as vectors. The disease affects all species of elm native to North America and Europe, but many Asiatic species have anti-fungal genes and are resistant. Fungal spores, introduced into wounds in the tree caused by the beetles, invade the xylem or vascular system. The tree responds by producing tyloses, effectively blocking the flow from roots to leaves. Woodland trees in North America are not quite as susceptible to the disease because they usually lack the root-grafting of the urban elms and are somewhat more isolated from each other. In France, inoculation of over three hundred clones of the European species with the fungus failed to find a single variety possessed of any significant resistance.

The first, less aggressive strain of the disease fungus, Ophiostoma ulmi, appeared in Europe in 1910 and had spread to North America by 1928, but declined in the 1940s. The second, far more virulent strain of the disease Ophiostoma novo-ulmi was identified in Europe in the late 1960s, and within a decade had killed over 20 million trees (approximately 75%) in the UK alone. Approximately three times more deadly, the origin of the new strain remains a mystery; earlier believed to have been endemic to China, surveys there in 1986 found no trace of it, although bark beetles were common. The most popular hypothesis is that it arose from a hybrid between the original O. ulmi and another strain endemic to the Himalaya, Ophiostoma himal-ulmi.[15]

While there is no sign of the current pandemic waning, there is some hope in the susceptibility of the fungus to a disease of its own caused by d-factors: naturally occurring virus-like agents that can severely debilitate it and reduce its sporulation.[16]

Owing to its geographical isolation and effective quarantine enforcement, Australia has so far been unaffected by Dutch Elm Disease, and as such retains many stands of English Elms; the long avenues of Royal Parade and St Kilda Road in Melbourne,[20] and Grattan Street in Carlton, Victoria, are three examples.

The provinces of Alberta and British Columbia in western Canada are also free of Dutch Elm disease. Aggressive means are being taken to prevent any occurrences of the disease in these two provinces. In fact, Alberta has the world's largest stands of elms unaffected by the disease, and many streets and parks in Edmonton and Calgary are still lined with large numbers of healthy mature trees.

The city of Brighton & Hove on the South Coast of England has retained a high proportion of its Elms. In the 1970s the Parks and Gardens departments of the two towns (since amalgamated into one city) pursued a vigorous policy of spotting and clearing infected elms, which is continued today within the designated "Elm Disease Management Area". Among the many trees thus preserved are several magnificent examples in and around the Royal Pavilion Gardens.

Resistant trees

- See also: List of Elm cultivars, hybrids and hybrid cultivars

Efforts to develop resistant cultivars began in the Netherlands in 1928 and continued, uninterrupted by World War II, until 1992.[17] Similar programmes were initiated in North America (1937), Italy (1978), and Spain (1990s). Research has followed two paths:

1. Hybrid cultivars

Owing to their innate resistance to Dutch elm disease, Asiatic species have been crossed with European species, or with other Asiatic elms, to produce trees highly resistant to disease and tolerant of native climates. After a number of false dawns in the 1970s, this approach has produced a range of fine cultivars now commercially available in North America and Europe. [21] [18] [19] [20] [21] [14] [22] However, some of these trees, notably those with the Siberian Elm U. pumila in their ancestry, will probably have a comparatively small mature size and lack the forms for which the iconic American Elm and English Elm were prized. Moreover, several of these trees exported to northwestern Europe have proven unsuited to the maritime climate conditions, notably because of their intolerance of ponding on poorly drained soils in winter. Dutch hybridizations invariably included the Himalayan Elm U. wallichiana as a source of anti-fungal genes and have proven more tolerant of wet ground; they should also ultimately reach a greater size. A number of highly resistant cultivars have been released since 2000, notably 'Nanguen' (Lutèce). [23] [24]

2. Species and species cultivars

In North America, careful selection has produced a number of trees not only resistant to disease, but also the droughts and extremely cold winters afflicting the continent. Research in the USA has concentrated on the American Elm U. americana, resulting in the release of highly resistant clones, notably 'Valley Forge'. Much work has also been done into the selection of Asiatic species and cultivars.[25] [26] In Europe, it is the unique example of the European White Elm Ulmus laevis which has received the most attention. Whilst this elm has little innate resistance to Dutch elm disease, it is not favoured by the vector bark beetles and thus only becomes colonized and infected when there are no other choices, a rare situation in western Europe. Research in Spain has suggested that it may be the presence of a triterpene, alnulin, which makes the tree bark unattractive to the beetle species that spread the disease.[27] However this has not been conclusively proved.[28]

Disclaimer

Elms take many decades to grow to maturity, and as the introduction of these cultivars is relatively recent, their long-term performance and ultimate size cannot be predicted with certainty. However, the National Elm Trial has been underway since 2005 as a large-scale scientific effort to assess strengths and weaknesses of the leading cultivars over a 10-year period.

Notable elm trees

- Sherwood Forest — the "Langton Elm" was a large tree that "was for a long time so remarkable as to have a special keeper", according to a book published in 1881.[29]

- The Biscarrosse Elm. Planted in 1350, this Smooth-leafed Elm Ulmus minor subsp. minor survives in the centre of Biscarrosse in the Landes region of south-west France, well isolated from disease-carrying Scolytus beetles.

- Oxford — "Joe Pullen's Tree" was planted in about 1700 by the Rev. Josiah Pullen, vice president of Magdalen Hall. Josiah Pullen "used to Walk to that place every day, sometimes twice a day", according to diarist Thomas Hearne. The famous essayist Richard Steele (1672–1729) said his regular walks as an undergraduate to the elm with Pullen helped him to reach a "florid old age". The elm became famous at Oxford and its fame grew with its age. In November 1795, Gentleman's Magazine reported that "Joe Pullen, the famous elm, upon Headington hills, had one of its large branches torn off and carried to a great distance." When new parliamentary district boundaries were drawn after the Reform Act 1832, the tree was named as a landmark helping to mark the boundary of the Parliamentary Borough of Oxford. In early 1847, the owner of the property arranged to have the tree torn down, and work started on it before protests put an end to the plan. By 1892, however, rot had set in, and the tree was torn down to its (large and tall) "stump". Early in the morning of October 13, 1909, vandals set fire to the stump. A plaque was soon after installed on the side wall of Davenport House in Cuckoo Lane, marking the spot. It reads[30]: Near this spot stood the famous elm planted by the Rev. Josiah Pullen about 1680 and known as Jo Pullen's Tree. Destroyed by fire on 13 October 1909.

"Herbie", New England's oldest and tallest elm, prior to its spread being reduced in 2008

"Herbie", New England's oldest and tallest elm, prior to its spread being reduced in 2008 - "Herbie" in Yarmouth, Maine, stood by present-day East Main Street (Route 88) from 1793-2010.[31] At 110 feet in height, it was believed to be, between 1997 and the date of its felling,[32] the oldest[33] and tallest of its kind in New England.[34] The tree, which partially stood in the front yard of a private residence, also had a 20-foot circumference and (until mid-2008) a 93-foot crown spread.[34] As of 2003, only twenty of Yarmouth's original 739 elms had survived Dutch elm disease.[35] In August 2009 it was revealed that, after battling fifteen bouts of Dutch elm disease, the tree had lost, and on January 19, 2010 it was cut down.[36]

Penn and Indians with treaty under the elm

Penn and Indians with treaty under the elm - The "Treaty Elm" — In what is now Penn Treaty Park, the founder of Pennsylvania, William Penn, is said to have entered into a treaty of peace with native Indians under a picturesque elm tree immortalized in a painting by Benjamin West. West made the tree, already a local landmark, famous by incorporating it into his painting after hearing legends (of unknown veracity) about the tree being the location of the treaty. No documentary evidence exists of any treaty Penn signed beneath a particular tree. On March 6, 1810 a great storm blew the tree down. Measurements taken at the time showed it to have a circumference of 24 feet (7.3 m), and its age was estimated to be 280 years. Wood from the tree was made into furniture, canes, walking sticks and various trinkets that Philadelphians kept as relics.

- The Liberty Tree on Boston Common that was a rallying point for the growing resistance to the rule of England over the American colonies.

- The Great Elm on Boston Common, supposed to have been in existence before the settlement of Boston, at the time of its destruction by the storm of the 15th of February 1876 measured 22 ft. in circumference.[37][38]

- Cambridge, Massachusetts — George Washington is said to have taken command of the American Continental Army under "the Washington Elm" in Cambridge on July 3, 1775. The tree survived until the 1920s and "was thought to be a survivor of the primeval forest". In 1872, a large branch fell from it and was used to construct a pulpit for a nearby church.[39] The tree, an American White Elm, became a celebrated attraction, with its own plaque, a fence constructed around it and a road moved in order to help preserve it.[40] The tree was cut down (or fell — sources differ) in October 1920 after an expert determined it was dead. The city of Cambridge had plans for it to be "carefully cut up and a piece sent to each state of the country and to the District of Columbia and Alaska," according to The Harvard Crimson.[41] As late as the early 1930s, garden shops advertised that they had cuttings of the tree for sale, although the accuracy of the claims has been doubted. A Harvard "professor of plant anatomy" examined the tree rings days after the tree was felled and pronounced it between 204 and 210 years old, making it at most 62 years old when Washington took command of the troops at Cambridge. The tree would have been a bit more than two feet in diameter (at 30 inches above ground) in 1773.[42] In 1896, an alumnus of the University of Washington, obtained a rooted cutting of the Cambridge tree and sent it to Professor Edmund Meany at the university. The cutting was planted, cuttings were then taken from it, including one planted on February 18, 1932, the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Washington, for whom Washington state is named. That tree remains on the campus of the Washington State Capitol. Just to the west of the tree is a small elm from a cutting made in 1979.[40]

- Washington, D.C. — George Washington supposedly had a favorite spot under an elm tree near the United States Capitol Building from which he would watch construction of the building. The elm stood near the Senate wing of the Capitol building until 1948.[39]

- Brown University — "Elmo", a large elm which "once defined the Thayer Street entrance to Brown’s new Watson Institute for International Studies" on the campus of the Providence, Rhode Island school, contracted Dutch Elm disease and was torn down in December 2003, according to a campus news release. The tree "was thought to have been between 80 and 100 years old. Wood from the tree, one of the largest on campus, was used in various student art projects.[43]

- Association Island — the General Electric think tank organization, the Elfun Society, founded in 1928 at Association Island in the Thousand Islands area of northern New York state, is named after a "famous" elm tree on the 65 acre isle. The tree died in the 1970s, but it survives in the elm tree logo still used by Elfun.[44]

- Philipsburg Elm - 280 year old 30 meter elm in Philipsburg, Quebec, dubbed "the king of elms", which was cut down in March 2009 after death from Dutch elm disease.[45][46]

- University of Georgia — "The MooCoo Tree," which stands in front of Theta Chi Fraternity, is one of the only Dutch Elm trees east of the Mississippi. Students are known to engage in the "MooCoo Challenge," which consists climbing into the Elm and consuming twelve beers before coming down.[47]

- New Haven, Connecticut had the first public tree planting program in America, producing a canopy of mature trees (including some large elms) that gave New Haven the nickname "The Elm City".[48] This later gave rise to the Yale song, Neath the Elms.

- Preston Park, Brighton, UK is the home of the two oldest Ulmus procera in the world, the Preston Twins. Both trees are over 400 years old and exceed 6 metres in girth. They have been regularly pollarded for many years and both trunks are hollow. The smaller, nearer the A23 London Road, can be entered from the east side; two people can stand comfortably inside it. The trees may be associated with the Medieval Manorial Scrolls kept in the County Records Office in Lewes.

- Provo, Utah, USA — Next to the USU Utah County Extension Office resides possibly a one of a kind elm tree. Officially it is a specimen of Ulmus americana, but unusual because it grows sideways, making it a tabletop elm tree. The tree was planted in 1927, and currently its several branches are supported by specialized braces to allow movement and growth. Every fall seven dump truck loads are required to remove all the leaves.[49][50]

Elm monographs

- Wilkinson, Gerald: Epitaph for the Elm (Hutchinson, London, 1978; ISBN 0-09-921280-3 / 0-09-921280-3). A photographic and pictorial celebration and general introduction.

- Clouston, Brian, & Stansfield, Kathy, eds.: After the Elm (Heinemann, London, 1979; ISBN 0-434-13900-9 / 0-434-13900-9). A general introduction, with a history of Dutch elm disease and proposals for re-landscaping in the aftermath of the pandemic. Illustrated.

- Richens, R. H.: Elm (Cambridge University Press, 1983; ISBN 0-521-24916-3 / 0-521-24916-3). A scientific, historical and cultural study, with a thesis on elm-classification, followed by a systematic survey of elms in England, region by region. Illustrated.

- Dunn, Christopher P., ed.: The Elms: Breeding, Conservation, and Disease-Management (New York, 2000; ISBN 0-7923-7724-9 / 0-7923-7724-9).

- Coleman, Max, ed.: Wych Elm (Edinburgh, 2009; ISBN 978-1-906129-21-7). A study of the species, with particular reference to the wych elm in Scotland and its use by craftsmen.

Elm in English literature

The impact of the elm on the landscape and human imagination is reflected in its occurrence in literature written on both sides of the Atlantic. An anthology can be found at The Elm in English literature.

See also

- List of Elm cultivars, hybrids and hybrid cultivars

- List of Elm species and varieties by scientific name

- List of Lepidoptera that feed on elms

References

- ↑ Rackham, O. (1980). Ancient woodland: its history, vegetation and uses. Edward Arnold, London

- ↑ Bean, W. J. (1981). Trees and shrubs hardy in Great Britain, 7th edition. Murray, London

- ↑ Fu, L., Xin, Y. & Whittemore, A. (2002). Ulmaceae, in Wu, Z. & Raven, P. (eds) Flora of China, Vol. 5 (Ulmaceae through Basellaceae). Science Press, Beijing, and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, USA. [1]

- ↑ Elwes, H. J. & Henry, A. (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland. Vol. VII. pp 1848-1929. Private publication [2]

- ↑ Heybroek, H. M., Goudzwaard, L, Kaljee, H. (2009). Iep of olm, karakterboom van de Lage Landen (:Elm, a tree with character of the Low Countries). KNNV, Uitgeverij. ISBN 9709050112819

- ↑ Hiemstra et al., (2005). Belang en toekomst van de iep in Nederland. Praktijkonderzoek Plant & Omgeving, Wageningen UR

- ↑ Solla, A., Bohnens, J., Collin, E., Diamandis, S., Franke, A., Gil, L., Burón, M., Santini, A., Mittempergher, L., Pinon, J., and Vanden Broeck, A. (2005). Screening European Elms for Resistance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Forest Science 51(2) 2005. Society of American Foresters, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

- ↑ Pinon J., Husson C., Collin E. (2005). Susceptibility of native French elm clones to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Annals of Forest Science 62: 1-8

- ↑ Collin, E. (2001). Elm. In Teissier du Cros (Ed.) (2001) Forest Genetic Resources Management and Conservation. France as a case study. Min. Agriculture, Bureau des Ressources Genetiques CRGF, INRA-DIC, Paris: 38-39.

- ↑ Brummitt, R. K. (1992). Vascular Plant Families & Genera. Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, London, UK.

- ↑ Elm. Niche Timbers. Accessed 19-08-2009.

- ↑ Elm. Niche Timbers. Accessed 19-08-2009.

- ↑ Osborne, P. (1983). The influence of Dutch elm disease on bird population trends. Bird Study, 1983: 27-38.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Santini, A., Pecori, F., Pepori, A. L., Ferrini, F., Ghelardini, L. (In press). Genotype × environment interaction and growth stability of several elm clones resistant to Dutch elm disease. Forest Ecology and Management. Elsevier B. V., Netherlands.

- ↑ Brasier, C. M. & Mehotra, M. D. (1995). Ophiostoma himal-ulmi sp. nov., a new species of Dutch elm disease fungus endemic to the Himalayas. Mycological Research 1995, vol. 99 (2), pp. 205-215 (44 ref.) ISSN 0953-7562. Elsevier, Oxford, UK.

- ↑ Brasier, C. M. (1996). New horizons in Dutch elm disease control. Pages 20-28 in: Report on Forest Research, 1996. Forestry Commission. HMSO, London, UK. [3]

- ↑ Burdekin, D. A. & Rushforth, K. D. (Revised by Webber J. F. 1996). Elms resistant to Dutch elm disease. Arboricultural Research Note 2/96. Arboricultural Advisory and Information Service, Alice Holt, Farnham, UK.

- ↑ Santamour, J., Frank, S. & Bentz, S. (1995). Updated checklist of elm (Ulmus) cultivars for use in North America. Journal of Arboriculture, 21:3 (May 1995), 121-131. International Society of Arboriculture, Champaign, Illinois, USA

- ↑ Smalley, E. B. & Guries, R. P. (1993). Breeding Elms for Resistance to Dutch Elm Disease. Annual Review of Phytopathology Vol. 31 : 325-354. Palo Alto, California

- ↑ Heybroek, H. M. (1983). Resistant Elms for Europe. In Burdekin, D. A. (Ed.) Research on Dutch elm disease in Europe. For. Comm. Bull. 60. pp 108 - 113

- ↑ Heybroek, H. M. (1993). The Dutch Elm Breeding Program. In Sticklen & Sherald (Eds.) (1993). Dutch Elm Disease Research, Chapter 3. Springer Verlag, New York, USA

- ↑ Mittempergher, L. & Santini, A. (2004) The history of elm breeding. Investigacion agraria: Sistemas y recursos forestales 13(1): 161-177 (2004)

- ↑ Girard, S. (2007). Dossier: L'orme: nouveaux espoirs? Forêt entreprise No. 175, Juillet 2007, Institut pour le developpement forestier, Paris.

- ↑ Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique. Lutèce, a resistant variety brings elms back to Paris.[4], Paris, France.

- ↑ Ware, G. (1995). Little-known elms from China: landscape tree possibilities. Journal of Arboriculture, (Nov. 1995). International Society of Arboriculture, Champaign, Illinois, USA. [5].

- ↑ Biggerstaffe, C., Iles, J. K., & Gleason, M. L. (1999). Sustainable urban landscapes: Dutch elm disease and disease-resistant elms. SUL-4, Iowa State University

- ↑ Martín-Benito D., Concepción García-Vallejo M., Pajares J. A., López D. 2005. Triterpenes in elms in Spain. Can. J. For. Res. 35: 199–205 (2005). [6]

- ↑ Pajares, J. A., García, S., Díez, J. J., Martín, D. & García-Vallejo, M. C. 2004. Feeding responses by Scolytus scolytus to twig bark extracts from elms. Invest Agrar: Sist Recur For. 13: 217-225. [7]

- ↑ [8] Wheeler, William Adolphus and Wheeler, Charles Gardner, Familiar Allusions: A Hand-book of Miscellaneous Information, 1881, Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, page 268, accessed Google digitized version October 20, 2007

- ↑ [9] Web page titled "Pullen's tree, Pullen's Lane, Headington" at the "Headington Website", accessed October 20, 2007

- ↑ "Will elm trees make their way back?" - St. Joseph's College Magazine

- ↑ According to the plaque on its trunk.

- ↑ Images of America: Yarmouth, Hall, Alan M., Arcadia (2002)

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 The National Register of Big Trees: 2000-01

- ↑ "Champion of Trees" - American Profile

- ↑ "Farewell to Herbie and a 'beautiful' relationship'" - Portland Press Herald, January 19 2010

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Elm". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Elm". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Great Elm on Boston Common

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 [10] Platt, Rutherford, "1001 Questions Answered About Trees", 1992, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-27038-6, accessed October 20, 2007

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 [11] Web page titled "Arthur Lee Jacobson: Trees of the Washington State Capitol Campus" at the Web site of Arthur Lee Jacobson (author of Trees of Seattle), text was part of a brochure, "originally published in 1993 as a 14-page brochure produced by the Washington State House of Representatives", according to the Web page, accessed October 20, 2007

- ↑ [12]"Big Day for Curio Hunter When Famous Elm is Cut", no byline, article in The Harvard Crimson, October 23, 1920, accessed October 20, 2007

- ↑ [13] Jack, J. G., "The Cambridge Washington Elm", article in the "Bulletin of Popular Information" of Harvard University's Arnold Arboretum, December 10, 1931, accessed October 20, 2007

- ↑ [14]"The Elm Tree Project: Brown’s once-mighty 'Elmo' is preserved through artists’ project", May 14, 2004, "Contact Mary Jo Curtis", accessed October 20, 2007

- ↑ [15] Web page titled "Association Island's History" at the Web site of the Association Island resort, accessed October 20, 2007

- ↑ [16] Ottawa Citizen, accessed December 8, 2008

- ↑ Radio-Canada, accessed March 10, 2009

- ↑ [17] Georgia, accessed December 8, 2008

- ↑ They’re Putting The “Elm” Back In “Elm City”

- ↑ [18]

- ↑ [19]

External links

- The Sauble Elm (Ontario, Canada)

- [22]. Northern Arizona University: Elm trials.

- Tree Family Ulmaceae Diagnostic photos of Elm species at the Morton Arboretum