Ferrocene

| Ferrocene | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

ferrocene, bis(η5-cyclopentadienyl)iron

|

|

|

Other names

dicyclopentadienyl iron

|

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 102-54-5 |

| PubChem | 11985121 |

| ChEBI | 30672 |

|

InChI

InChI=InChI=1/2C5H5.Fe/c2*1-2-4-5-3-1;/h2*1-5H;

|

|

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C10H10Fe |

| Molar mass | 186.04 g/mol |

| Appearance | light orange powder |

| Density | 1.107 g/cm3 (0°C), 1.490 g/cm3 (20 °C)[1] |

| Melting point |

174 °C |

| Boiling point |

249 °C |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble in water, soluble in most organic solvents |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds | cobaltocene, nickelocene, chromacene, bis(benzene)chromium |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) |

|

| Infobox references | |

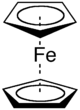

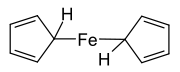

Ferrocene is an organometallic compound with the formula Fe(C5H5)2. It is the prototypical metallocene, a type of organometallic chemical compound consisting of two cyclopentadienyl rings bound on opposite sides of a central metal atom. Such organometallic compounds are also known as sandwich compounds.[2] The rapid growth of organometallic chemistry is often attributed to the excitement arising from the discovery of ferrocene and its many analogues.

Contents |

History

Ferrocene was first prepared unintentionally. In 1951, Pauson and Kealy at Duquesne University reported the reaction of cyclopentadienyl magnesium bromide and ferric chloride with the goal of oxidatively coupling the diene to prepare fulvalene. Instead, they obtained a light orange powder of "remarkable stability."[3][4] This stability was accorded to the aromatic character of the negative charged cyclopentadienyls, but the sandwich structure of the η5 (pentahapto) compound was not recognized by them.

Robert Burns Woodward and Geoffrey Wilkinson deduced the structure based on its reactivity.[5] Independently Ernst Otto Fischer also came to the conclusion of the sandwich structure and started to synthesize other metallocenes such as nickelocene and cobaltocene.[6][7] Ferrocene's structure was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography.[8][9] Its distinctive "sandwich" structure led to an explosion of interest in compounds of d-block metals with hydrocarbons, and invigorated the development of the flourishing study of organometallic chemistry. In 1973 Fischer of the Technische Universität München and Wilkinson of Imperial College London shared a Nobel Prize for their work on metallocenes and other aspects of organometallic chemistry.[10]

Structure and bonding

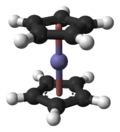

The iron atom in ferrocene is normally assigned to the +2 oxidation state, as can be shown using Mössbauer spectroscopy. Each cyclopentadienyl (Cp) ring is then allocated a single negative charge, bringing the number of π-electrons on each ring to six, and thus making them aromatic. These twelve electrons (six from each ring) are then shared with the metal via covalent bonding, which, when combined with the six d-electrons on Fe2+, results in the complex having an 18-electron, noble gas electron configuration.

The lack of individual bonds between the carbon atoms of the Cp ring and the Fe2+ ion results in the Cp rings to freely rotate about the Cp(centroid)-Fe-Cp(centroid) axis, as observed by nuclear magnetic resonance[11] and scanning tunneling microscopy.[12][13]

The carbon-carbon bond distances are 1.40 Å within the five membered rings, and the Fe-C bond distances are 2.04 Å.

Synthesis and handling properties

The first reported[14] synthesis of ferrocene used the Grignard reagent cyclopentadienyl magnesium bromide, which can be prepared by reacting cyclopentadiene with magnesium and bromethane in anhydrous benzene. Iron(II) chloride is then suspended in anhydrous diethyl ether and added to the Grignard reagent. The reaction sequence is:

- CH3CH2Br + Mg + C5H6 → C5H5MgBr + CH3CH3

- 2 C5H5MgBr + FeCl2 → Fe(C5H5)2 + MgCl2 + MgBr2

Numerous other syntheses have been reported, including the direct reaction of gas phase cyclopentadiene with metallic iron[15] at 623 K and with iron pentacarbonyl.[16]

- Fe + 2 C5H6(g) → Fe(C5H5)2 + H2(g)

- Fe(CO)5 + 2 C5H6(g) → Fe(C5H5)2 + 5 CO(g) + H2(g)

Modern and more efficient preparative methods are generally a modification of the original transmetalation sequence using either commercially available sodium cyclopentadienide[17] or freshly cracked cyclopentadiene and potassium hydroxide[18]

with anhydrous iron(II) chloride in ethereal solvents:

- 2 NaC5H5 + FeCl2 → Fe(C5H5)2 + 2 NaCl

- FeCl2.4H2O + 2 C5H6 + 2 KOH → Fe(C5H5)2 + 2 KCl + 6 H2O

As expected for a symmetric and uncharged species, ferrocene is soluble in normal organic solvents, such as benzene, but is insoluble in water. Ferrocene is an air-stable orange solid that readily sublimes, especially upon heating in a vacuum. It is stable to temperatures as high as 400 °C.[19] The following table gives typical values of vapor pressure of ferrocene at different temperatures:[20]

| pressure(Pa) | 1 | 10 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| temperature(K) | 298 | 323 | 353 |

Reactions

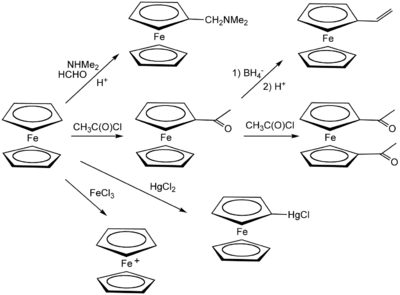

With electrophiles

Ferrocene undergoes many reactions characteristic of aromatic compounds, enabling the preparation of substituted derivatives. A common undergraduate experiment is the Friedel-Crafts reaction of ferrocene with acetic anhydride (or acetyl chloride) in the presence of phosphoric acid as a catalyst.

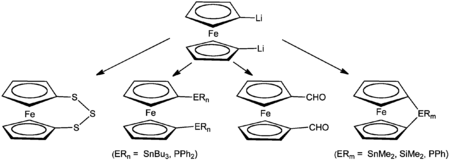

Lithiation

Ferrocene reacts readily with butyl lithium to give 1,1'-dilithioferrocene, which in turn is a versatile nucleophile. But reaction of Ferrocene with t-BuLi produces monolithioferrocene only. [21] These approaches are especially useful methods to introduce main group functionality, e.g. using S8, chlorophosphines, chlorosilanes. The strained compounds undergo ring-opening polymerization.[22]

Phosphorus derivatives

Many phosphine derivatives of ferrocenes are known and some are used in commercialized processes. Simplest and best known is 1,1'-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (dppf) prepared from dilithioferrocene. Other routes to such ligands are known. For example, in the presence of aluminium chloride Me2NPCl2 and ferrocene react to give ferrocenyl dichlorophosphine,[23] while treatment with phenyldichlorophosphine under similar conditions forms P,P-diferrocenyl-P-phenyl phosphine.[24] In common with anisole the reaction of ferrocene with P4S10 forms a dithiadiphosphetane disulfide.[25]

Redox chemistry

Unlike the majority of hydrocarbons, ferrocene undergoes a one-electron oxidation at a low potential, around 0.5 V vs. a saturated calomel electrode (SCE). It is also been used as standard in electrochemistry as Fc+/Fc = 0.64 V vs. NHE. Some electron rich hydrocarbons (e.g., aniline) also are oxidized at low potentials, but only irreversibly. Oxidation of ferrocene gives a stable cation called ferrocenium. On a preparative scale, the oxidation is conveniently effected with FeCl3 to give the blue-colored ion, [Fe(C5H5)2]+, which is often isolated as its PF6− salt. Alternatively, silver nitrate may be used as the oxidizer.

Ferrocenium salts are sometimes used as oxidizing agents, in part because the product ferrocene is fairly inert and readily separated from ionic products.[26] Substituents on the cyclopentadienyl ligands alters the redox potential in the expected way: electron withdrawing group such as a carboxylic acid shift the potential in the anodic direction (i.e. made more positive), whereas electron releasing groups such as methyl groups shift the potential in the cathodic direction (more negative). Thus, decamethylferrocene is much more easy to oxidise than ferrocene itself. Ferrocene is often used as an internal standard for calibrating redox potentials in non-aqeous electrochemistry.

Stereochemistry

A variety of substitution patterns are possible with ferrocene including substition at one or both of the rings. The most common substitution patterns are 1-substituted (one substituent on one ring) and 1,1'-disubstituted (one substituent on each ring). Usually the rings rotate freely, which simplifies the isomerism. Disubstituted ferrocenes can exist as either 1,2- and 1,1' isomers, which are not interconvertible. 1,2-Heterodisubstituted ferrocenes are chiral.

Applications of ferrocene and its derivatives

Ferrocene and its numerous derivatives have no large-scale applications, but have many niche uses that exploit the unusual structure (ligand scaffolds, pharmaceutical candidates), robustness (anti-knock formulations, precursors to materials), and redox (reagents and redox standards).

Fuel additives

Ferrocene and its derivatives are antiknock agents used in the fuel for petrol engines; they are safer than tetraethyllead, previously used.[27] It is possible to buy at Halfords in the UK, a petrol additive solution which contains ferrocene which can be added to unleaded petrol to enable it to be used in vintage cars which were designed to run on leaded petrol.[28] The iron containing deposits formed from ferrocene can form a conductive coating on the spark plug surfaces.

In diesel-fuelled engines, ferrocene reduces the production of soot.

Ferrocene is available under multiple brand names, including Ferox.

Pharmaceutical

Some ferrocenium salts exhibit anticancer activity, and an experimental drug has been reported which is a ferrocenyl version of tamoxifen.[29] The idea is that the tamoxifen will bind to the estrogen binding sites, resulting in a cytotoxicity effect.[29][30][31]

Materials chemistry

Ferrocene, being readily sublimed, can be used to deposit certain kinds of fullerenes, especially carbon nanotubes. Due to the fact that many organic reactions can be used to modify ferrocenes, it is the case that vinyl ferrocene can be made. The vinyl ferrocene can be made by a Wittig reaction of the aldehyde, a phosphonium salt and sodium hydroxide.[32] The vinyl ferrocene can be converted into a polymer which can be thought of as a ferrocenyl version of polystyrene (the phenyl groups are replaced with ferrocenyl groups).

Ferrocene is also used as a nano-sized "loom" in the manufacture of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene's very long fibers, which are used to manufacture newer types of bulletproof vest fabric.

As a ligand scaffold

Chiral ferrocenyl phosphines are employed as ligands for transition-metal catalyzed reactions. Some of them have found industrial applications in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. For example, the diphosphine 1,1'-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (dppf) is a valuable ligand for palladium-coupling reactions.

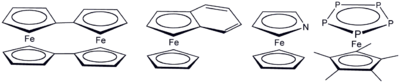

Derivatives and variations

Many other hydrocarbons can be used instead of cyclopentadienyl. For example, indenyl can be used in place of the cyclopentadienyl to form bisbenzoferrocene.[33]

The carbon atoms can be replaced by heteroatoms as illustrated by Fe(η5-C5Me5)(η5-P5) and Fe(η5-C5H5)(η5-C4H4N) ("azaferrocene"). Azaferrocene arises from decarbonylation of Fe(η5-C5H5)(CO)2(η1-pyrrole) in cyclohexane.[34] This compound on boiling under reflux in benzene is converted to ferrocene.[35]

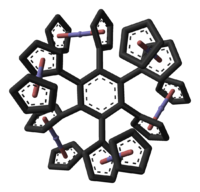

Because of the ease of substitution, many structurally unusual ferrocene derivatives have been prepared. For example, the penta(ferrocenyl)cyclopentadienyl ligand,[36] features a cyclopentadiene derivatised with five ferrocene substituents.

cyclopentadienyl.png)

In hexaferrocenylbenzene, all six positions on a benzene molecule have ferrocenyl substituents (R).[37] X-ray diffraction analysis of this compound confirms that the cyclopentadienyl ligands are not co-planar with the benzene core but have alternating dihedral angles of +30° and −80°. Due to steric crowding the ferrocenyls are slightly bent with angles of 177° and have elongated C-Fe bonds. The quaternary cyclopentadienyl carbon atoms are also pyramidalized.[38]

References

- ↑ "Ferrocene(102-54-5)". http://www.chemicalbook.com/ProductMSDSDetailCB1414721_EN.htm. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ Federman Neto, Alberto; Pelegrino, Alessandra Caramori; Darin, Vitor Andre (2004). "Ferrocene: 50 Years of Transition Metal Organometallic Chemistry — From Organic and Inorganic to Supramolecular Chemistry". ChemInform 35. doi:10.1002/chin.200443242.

- ↑ T. J. Kealy, P. L. Pauson (1951). "A New Type of Organo-Iron Compound". Nature 168: 1039. doi:10.1038/1681039b0.

- ↑ A second group independently discovered ferrocene. See: S. A. Miller, J. A. Tebboth, and J. F. Tremaine (1952) "Dicyclopentadienyliron," Journal of the Chemical Society (London) , pages 632-635. See also: Pierre Laszlo and Roald Hoffmann (2000) "Ferrocene: Ironclad History of Rashomon Tale?," Angewandte Chemie (International Edition), vol. 39, no. 1, pages 123-124.

- ↑ G. Wilkinson, M. Rosenblum, M. C. Whiting, R. B. Woodward (1952). "The Structure of Iron Bis-Cyclopentadienyl". Journal of the American Chemical Society 74: 2125–2126. doi:10.1021/ja01128a527.

- ↑ E. O. Fischer, W. Pfab (1952). "Zur Kristallstruktur der Di-Cyclopentadienyl-Verbindungen des zweiwertigen Eisens, Kobalts und Nickels". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B 7: 377–379.

- ↑ A third group independently determined the structure of ferrocene. See: P. F. Eiland and R. Pepinsky (1952) "X-ray examination of iron biscyclopentadienyl," Journal of the American Chemical Society, vol. 74, page 4971. See also: Pierre Laszlo and Roald Hoffmann (2000) "Ferrocene: Ironclad History of Rashomon Tale?," Angewandte Chemie (International Edition), vol. 39, no. 1, pages 123-124.

- ↑ J. Dunitz, L. Orgel, A. Rich (1956). "The crystal structure of ferrocene". Acta Crystallographica 9: 373–375. doi:10.1107/S0365110X56001091.

- ↑ Pierre Laszlo, Roald Hoffmann, (2000). "Ferrocene: Ironclad History or Rashomon Tale?". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 39: 123–124. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<123::AID-ANIE123>3.0.CO;2-Z.

- ↑ "Press Release: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1973". The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. 1973. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1973/press.html.

- ↑ E. W. Abel, N. J. Long, K. G. Orrell, A. G. Osborne, V. Sik (1991). "Dynamic NMR studies of ring rotation in substituted ferrocenes and ruthenocenes". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 403: 195–208. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(91)83100-I.

- ↑ L. F. N. Ah Qune, K. Tamada, M. Hara (2008). "Self-Assembling Properties of 11-Ferrocenyl-1-Undecanethiol on Highly Oriented Pyrolitic Graphite Characterized by Scanning Tunneling Microscopy". E-Journal of Surface Science and Nanotechnology 6: 119–123. doi:10.1380/ejssnt.2008.119.

- ↑ Self-Assembling Properties of 11-Ferrocenyl-1-Undecanethiol on Highly Oriented Pyrolitic Graphite Characterized by Scanning Tunneling Microscopy

- ↑ Kealy, T. J.; Pauson, P. L. (1951). Nature 168: 1039.

- ↑ Wilkinson, G.; Pauson, P. L.; Cotton, F. A. (1954). Journal of the American Chemical Society 76: 1970.

- ↑ Wilkinson, G.; Cotton, F. A. (1959). Progress in Inorganic Chemistry 1: 1-124.

- ↑ Geoffrey Wilkinson (1963), "Ferrocene", Org. Synth., http://www.orgsyn.org/orgsyn/orgsyn/prepContent.asp?prep=cv4p0473; Coll. Vol. 4: 473

- ↑ Jolly, W. L., The Synthesis and Characterization of Inorganic Compounds, Prentice-Hall: New Jersey, 1970.

- ↑ Solomons, Graham, and Craig Fryhle. Organic Chemistry. 9th ed. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006.

- ↑ Monte, Manuel J. S.; Santos, Luís M. N. B. F.; Fulem, Michal; Fonseca, José M. S.; Sousa, Carlos A. D. (2006). "New Static Apparatus and Vapor Pressure of Reference Materials: Naphthalene, Benzoic Acid, Benzophenone, and Ferrocene". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 51: 757. doi:10.1021/je050502y.

- ↑ F Rebierea, O Samuela and H.B Kagan "A convenient method for the preparation of monolithioferrocene" Tetrahedron Letters Volume 31, Issue 22, 1990, Pages 3121-3124. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94710-5

- ↑ David E. Herbert, Ulrich F. J. Mayer, Ian Manners “Strained Metallocenophanes and Related Organometallic Rings Containing pi-Hydrocarbon Ligands and Transition-Metal Centers” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, volume 46, 5060 - 5081. doi:10.1002/anie.200604409

- ↑ G.R. Knox, P.L. Pauson and D. Willison (1992). "Ferrocene derivatives. 27. Ferrocenyldimethylphosphine". Organometallics 11 (8): 2930–2933. doi:10.1021/om00044a038.

- ↑ G.P. Sollott, H.E. Mertwoy, S. Portnoy and J.L. Snead (1963). "Unsymmetrical Tertiary Phosphines of Ferrocene by Friedel-Crafts Reactions. I. Ferrocenylphenylphosphines". J. Org. Chem. 28: 1090–1092. doi:10.1021/jo01039a055.

- ↑ Mark R. St. J. Foreman, Alexandra M. Z. Slawin and J. Derek Woollins (1996). "2,4-Diferrocenyl-1,3-dithiadiphosphetane 2,4-disulfide; structure and reactions with catechols and [PtCl2(PR3)2](R = Et or Bun)". J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans.,: 3653 – 3657. doi:10.1039/DT9960003653.

- ↑ N. G. Connelly, W. E. Geiger (1996). "Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry". Chemical Reviews 96: 877–910. doi:10.1021/cr940053x.

- ↑ Application of fuel additives

- ↑ U.S. Patent 4,104,036

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 S. Top, A. Vessières, G. Leclercq, J. Quivy, J. Tang, J. Vaissermann, M. Huché and G. Jaouen (2003). "Synthesis, Biochemical Properties and Molecular Modelling Studies of Organometallic Specific Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs), the Ferrocifens and Hydroxyferrocifens: Evidence for an Antiproliferative Effect of Hydroxyferrocifens on both Hormone-Dependent and Hormone-Independent Breast Cancer Cell Lines". Chemistry, a European Journal 9 (21): 5223–36. doi:10.1002/chem.200305024. PMID 14613131.

- ↑ Ron Dagani (16 September 2002). "The Bio Side of Organometallics". Chemical and Engineering News 80 (37): 23–29. http://pubs.acs.org/cen/science/8037/8037sci1.html.

- ↑ S. Top, B. Dauer, J. Vaissermann and G. Jaouen (1997). "Facile route to ferrocifen, 1-[4-(2-dimethylaminoethoxy)]-1-(phenyl-2-ferrocenyl-but-1-ene), first organometallic analogue of tamoxifen, by the McMurry reaction". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 541: 355–361. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(97)00086-7.

- ↑ Liu, Wan-yi; Xu, Qi-hai; Ma, Yong-xiang; Liang, Yong-min; Dong, Ning-li; Guan, De-peng,J. Organomet. Chem., 2001, 625, 128 - 132

- ↑ Waldbaum, B (1999). "Novel organoiron compounds resulting from the attempted syntheses of dibenzofulvalene complexes". Inorganica Chimica Acta 291: 109. doi:10.1016/S0020-1693(99)00123-1.

- ↑ Zakrzewski, J (1990). "An improved photochemical synthesis of azaferrocene". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 388: 175. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(90)85359-7.

- ↑ Efraty, Avi.; Jubran, Nusrallah.; Goldman, Alexander. (1982). "Chemistry of some .eta.5-pyrrolyl- and .eta.1-N-pyrrolyliron complexes". Inorganic Chemistry 21: 868. doi:10.1021/ic00133a006.

- ↑ Y. Yu, A.D. Bond, P. W. Leonard, K. P. C. Vollhardt, G. D. Whitener (2006). "Syntheses, Structures, and Reactivity of Radial Oligocyclopentadienyl Metal Complexes: Penta(ferrocenyl)cyclopentadienyl and Congeners". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 45 (11): 1794–1799. doi:10.1002/anie.200504047.

- ↑ Yong Yu, Andrew D. Bond, Philip W. Leonard, Ulrich J. Lorenz, Tatiana V. Timofeeva, K. Peter C. Vollhardt, Glenn D. Whitener and Andrey A. Yakovenko (2006). "Hexaferrocenylbenzene". Chemical Communications: 2572–2574. doi:10.1039/b604844g.

- ↑ Also, the benzene core has a chair conformation with dihedral angles of 14° and displays bond length alternation between 142.7 pm and 141.1 pm, both indications of steric crowding of the substituents.

Further reading

- Announcement of the discovery of ferrocene, but with wrong structure

- Kealy, T. J., Pauson, P. L. (1951). "A New Type of Organo-iron Compound". Nature 168: 1039–40. doi:10.1038/1681039b0.

- Miller, S. A., Tebboth, J. A., Tremaine, J. F. (1952). "114. Dicyclopentadienyliron". Journal of the Chemical Society: 632–635. doi:10.1039/JR9520000632.

- Announcement of the correct 'sandwich' structure

- Wilkinson, G., Rosenblum, M., Whiting, M. C., Woodward, R. B. (1952). "The Structure of Iron Bis-Cyclopentadienyl". Journal of the American Chemical Society 74: 2125–2126. doi:10.1021/ja01128a527.

- Fischer, E. O., Pfab, W. (1952). "Cyclopentadien-Metallkomplexe, ein neuer typ metallorganischer Verbindungen". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B 7: 377–379.

- Others

- Dunitz, J. D., Orgel, L. E. (1953). "Bis-Cyclopentadienyl - A Molecular Sandwich". Nature 171: 121–122. doi:10.1038/171121a0.

- Pauson, P. L. (2001). "Ferrocene-how it all began". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 637-639: 637–639. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(01)01126-3.

- Gerard Jaouen (ed.) (2006). Bioorganometallics: Biomolecules, Labeling, Medicine. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-30990-0. (discussion of biological role of ferrocene and related compounds)