Haida

|

| Haida carver Saaduuts, 2007 |

| Total population |

|---|

| c. 2,000[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Canada (British Columbia) United States (Alaska) |

| Languages |

|

English, Haida |

The Haida are an indigenous nation of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Haida territories lie in both Canada and the United States, as do those of the Tlingit, and Tsimshian. The Haida territories comprise the archipelago of Haida Gwaii (formerly referred to as the Queen Charlotte Islands) in British Columbia. In the Haida language Haida Gwaii translates to "islands of the people"). Historically, and still today, "Kaigani Haida" families live in Southern Alaska and the southern half of Prince of Wales Island in the southernmost Alaska Panhandle.

The term "Haida Nation" refers both to the people as a whole and also to their government on Canadian territory, the Council of the Haida Nation; the government for those in the United States is the Central Council Tlingit Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska. Their ancestral language has erroneously been classified as one of the Na-Dene languages, but today is considered to be a language isolate.[2] In addition to those Haida residing on Haida Gwaii, Southern Alaska, and Prince of Wales Island, there are also many Haidas in various urban areas in the western United States.

Haida society continues to be very engaged in the production of a robust and highly stylized art form. While frequently expressed in large wooden carvings (totem poles), Chilkat weaving, or ornate jewellery, it is also moving quickly into the work of populist expression such as Haida manga. Haida art is a leading component of Northwest Coast art.

Contents |

History

The Canadian Museum of Civilization offers a detailed look at the Haida, who were known for their seamanship, their martial inclination and their practice of slavery. The Museum indicates that the Haida "created notions of wealth", and credits the Haida with the introduction of the totem pole and the bentwood box.[3]

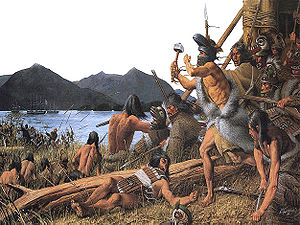

Haidas were traditionally known as ruthless warriors and slave traders, raiding as far as California. Haida oral narratives record journeys as far north as the Bering Sea, and one account implies that even Asia was visited by Haidas before Europeans entered the Pacific. The Haida's ability to travel was dependent upon a supply of ancient Western Red cedar trees that were carved and shaped into their famous Pacific Northwest Canoes. Haida warriors entered battle with red cedar armor, wooden shields, stone maces and atlatls. War helmets were carved. These techniques are unknown to anyone other than the Haida people as they have kept it secret for many years. It is still unknown how the Haida would carve their war helmets and how they looked.

The Haida were feared along the coast because of their practice of making lightning raids against which their enemies had little defense. Their great skills of seamanship, their superior craft and their relative protection from retaliation in their island fortress added to the aggressive posture of the Haida towards neighboring tribes. Diamond Jenness, an early anthropologist at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, caught their essence in his description of the Haida as the "Indian Vikings of the North West Coast":

Those were stirring times, about a century ago, when the big Haida war canoes, each hollowed out of a single cedar tree and manned by fifty or sixty warriors, traded and raided up and down the coast from Sitka in the north to the delta of the Fraser River in the south. Each usually carried a shaman or medicine man to catch and destroy the souls of enemies before an impending battle; and the women who sometimes accompanied the warriors fought as savagely as their husbands.

The Haida went to war to acquire objects of wealth, such as coppers and Chilkat blankets, that were in short supply on the islands, but primarily for slaves, who enhanced their productivity or were traded to other tribes. High-ranking hostages were also the source of other property received in ransom such as crest designs, dances and songs.

Even prehistorically, the Haida engaged in sea battles. Most tribes avoided sea battles with the Haida and tried to lure them ashore for a more equitable fight. The Tsimshian developed a signal-fire system to alert their villages on the Skeena River as soon as Haida invaders reached the mainland.

The incidence of warfare was undoubtedly accelerated in the half century from 1780 to 1830, when the Haida had no effective enemies except the many European and American traders on their shores who would rather trade than fight. During this period, the Haida successfully captured more than half a dozen ships. One was the ship Eleanora, taken by chiefs of the village of Skungwai (or Ninstints) in retaliation for the maltreatment Chief Koyah had received from its captain. An even more spectacular event was the capture of the ship Susan Sturgis.

In such conflicts, the Haida quickly learned the newcomers' fighting tactics, which they used to good effect in subsequent battles, as Jacob Brink notes:

As early as 1795, a British trading ship fired its cannons at a village in the central part of the archipelago because some of the crew had been killed by the inhabitants, and the survivors had to put hastily to sea when the Indians fired back at them. They found out later that the Indians had used a cannon and ammunition raided from an American Schooner a few years earlier.

Swivel guns were added to many Haida war canoes, although initially the recoil on discharge caused the hulls of many craft to split.

Fortified sites were part of the defensive strategy of all Northwest Coast groups for at least 2,000 years. Captain James Cook was so impressed with one Haida fort off the west coast of Graham Island that he called it Hippah Island after the Māori forts he had seen in New Zealand. Military defences at Haida forts included stout palisades, rolling top-log defences, heavy trapdoors and fighting platforms supplied with stores of large boulders to hurl at invaders.

The Haidas were two Northwest Coast Nations that excercised a great deal of control in preserving their culture & in their connections with foreigners in their respective territories during the sometimes hostile Maritime Fur Trade. During the sometimes racial fur trade, the Haidas retailiated against violence with enslaving or simply massacring Russian, European, and American trading vessels. The two Haida Nations confronted the economic invasion & manipulated it to serve their own ends. "The Kaigani were calculated savages," by Britain's standards, " and were the most dangerous Indians on the Northwest Coast to deal with." Russia first entered the Empire of the Tlingit Indians in 1741, followed by Spain in 1774, England in 1778, & finally, America, in 1788. These trespassers penetrated as far as the Haida Empires of Kaigani & Queen Charlotte Islands. Ballistic Weapons were bought from either the Spaniards or British.

The Battle of Sitka in 1804 was a significant year in history. The Napoleonic Wars were starting, with the participation of both England & Russia. During the Battles of Sitka, the Tlingit Empire, Tsimshian Empire, & Kaigani Empire formed an Alliance against Russia. Trespass by the Russian Empire was a strategic reason for the Alliance and their Declaration of War. Several American ships were destroyed by organized military asymmetric assaults from the Kaigani Empire during this time. Although the Russians took Sitka from the Tlingits, they were unsuccessful in taking any Haida and Tsimshian territory. After the Battles of Sitka, the Haidas had confrontations with outlaw gangs of the Alaskan Gold Rush, and they also continued conflict with the Tsimshian Empire.

While American gold miners were forced out of the Haida's territory during the 1850's, their slave trade "officially" ended in 1834, but the Haidas continued trading successfully with 585 slaves in 1880.

According to the Museum, like other groups on the Northwest Coast, the Haida defended themselves with fortifications, including palisades, trapdoors and platforms. They took to water in large ocean-going canoes, large enough to accommodate as many as 60 paddlers, each created from a single Western Red cedar tree. The aggressive tribe were particularly feared in sea battles, although they did respect rules of engagement in their conflicts.[3] The Haida developed effective weapons for boat-based battle, including a special system of stone rings weighing 18 to 23 kilograms (40 to 51 lb) which could destroy an enemy's dugout canoe and be reused after the Haida pulled it back with the attached cedar bark rope. The Haida took captives from defeated enemies. Between 1780 and 1830, the Haida turned their aggression towards European and American traders. Among the half-dozen ships the tribe captured were the Eleanor and the Susan Sturgis. The tribe made use of the weapons they so acquired, utilizing cannons and canoe-mounted swivel guns.[3]

In 1856, an expedition in search of a route across Vancouver Island was at the mouth of the Qualicum River when they observed a large fleet of Haida canoes approaching and hid in the forest. They observed these attackers holding human heads. When they came to the mouth of the river, they came upon the charred remains of the village of the Qualicum people and the mutilated bodies of its inhabitants, with only one survivor, an elderly woman, hiding terrified inside a tree stump. [4] Also in 1856, the USS Massachusetts was sent from Seattle to nearby Port Gamble, where indigenous raiding parties made up of Haida (from territory claimed by the British) and Tongass (from territory claimed by the Russians) had been attacking and enslaving the Coast Salish people there. When the Haida and Tongass (Cape Fox tribe Tlingit) warriors refused to acknowledge American jurisdiction and to hand over those among them who had attacked the Puget Sound communities, a battle ensued in which 26 Native Americans and one government soldier were killed. In the aftermath of this, Colonel Isaac Ebey, a US military officer and the first settler on Whidbey Island, was shot and beheaded on 11 August 1857 by a small Haida fleet, in retaliation for the killing of a respected Haida citizen during similar raids the year before. British authorities demurred to pursue or confront any northern indigenous nations as they passed northward through waters the British nevertheless claimed authority over and Ebey's killers were never caught.[5][6]

Villages

Historical Haida villages were[7]:

- Kiusta

- Kung

- Yan

- Hiellan

- Skidegate (Graham Island)

- Cha'atl

- Haina

- Kaisun

- Cumshewa (Moresby Island)

- Skedans aka Koona or Q'una.

- Tanu (New Clew), Louise Island

- Ninstints (Sgang Gway, aka Anthony Island)

- Masset The name Masset, received from pre British contact between Haidas and the Spanish, actually includes three separate and adjoining communities,

- Atewaas (white slope town)

- Jaahguhl

- Kayung

- Hlk'yah GaawGa (Windy Bay) (Lyell Island)[8]

- Klinkwan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Sukkwan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Howkan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Kasaan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

Calendar

The Haidas' calendar:

- April/May- Gansgee 7laa kongaas

- May/Early June- Wa.aay gwaalgee

- June/July- Kong koaas

- July/August- Sgaana gyaas

- August/September- K'ijaas

- September/October- K'alayaa Kongaas

- October/November- K'eed adii

- November/December- Jid Kongaas

- December/January- Kong gyaangaas

- January/February- Hlgiduum kongaas

- February/March- Taan kongaas

- March- Xiid gayaas

- April- Wiid gyaas

Notable Haidas

- Florence Davidson, artist and memoirist

- Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, artist

- Reg Davidson, carver

- Robert Davidson, carver

- Diane Douglas-Willard, basket weaver and educator

- Michael Douglas, lawyer

- Freda Diesing, carver

- Charles Edenshaw, carver, jeweler, and painter

- Gerry Marks, artist

- Bill Reid, carver, sculptor and jeweler

- Jay Simeon, artist

- Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw), artist and politician, current President of the Council of the Haida Nation

- Richard H. Carle, Sr., Chief Y'eil Iwaans (Big Raven)

- Delores Churchill, artist, basketweaver

Notable Haida in history

- Skaay, mythteller

- Cumshewa, chief

- Koyah, chief

- Cuneah, chief at Kiusta

- Captain Gold

- Chief Masset

- Chief Skidegate

Anthropologists and scholars

This is an incomplete list of anthropologists and scholars who have done research on the Haida.

- Marius Barbeau

- Robert Bringhurst

- Wilson Duff

- Christie Harris

- Bill Holm

- Marianne Boelscher Ignace

- John R. Swanton

- Frederick White

- John Enrico

- Clealls John Medicine Horse Kelly

- Gillian Crowther

- Emily Carr

- Mary Lee Stearns

- Charles F. Newcombe

- Frances Poole

- Daryl Fedje

- Kathleen E. Dalzell

- Nancy J. Turner

- George Peter Murdock

See also

- Haida Argillite Carvings

- Haida Islands (Central Coast)

- Haida language

- Haida manga

- Haida mythology

- HMCS Haida

Further reading

- Blackman, Margaret B. (1982; rev. ed., 1992) During My Time: Florence Edenshaw Davidson, a Haida Woman. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Boelscher, Marianne (1988) The Curtain Within: Haida Social and Mythical Discourse. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Bringhurst, Robert (2000) A Story as Sharp as a Knife: The Classical Haida Mythtellers and Their World. Douglas & McIntyre.

- Donald, Leland (1997) Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. University of California Press.

- Andersen, Doris (1974) Slave of the Haida. Macmillan Co. of Canada.

- Kushner, Howard (1975) Conflict on the Northwest Coast: American-Russian Rivalry in the Pacific Northwest. Greenwood Press.

- Nora Marks Dauenhauer, Richard Dauenhauer, Lydia T. Black (2008) "Anooshi Lingit Aani Ka/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 And 1804." University of Washington Press.

- Fisher, Robin (1992) "Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890." UBC Press.

- Geduhn, Thomas (1993) "Eigene und fremde Verhaltensmuster in der Territorialgeschichte der Haida." (Mundus Reihe Ethnologie, Band 71.) Bonn: Holos Verlag.

- Harris, Christie (1966) Raven's Cry. New York: Atheneum.

- Harrison, Charles (1925) Ancient Warriors of the North Pacific - The Haidas, Their Laws, Customs and Legends. H.F. & G. Witherby.

- Huteson, Pamela (2007) "Transformation Masks" Surrey, B.C. Canada: Hancock House Publishers LTD. ISBN- 13 978-0-88839-635-8 and ISBN- 10 0-88839-635-X

- Kan, Sergei (1993) SYMBOLIC IMMORTALITY; The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century Smithsonian.

- Snyder, Gary (1979) He Who Hunted Birds in His Father's Village. San Francisco: Grey Fox Press.

- Stearns, Mary Lee (1981) Haida Culture in Custody: The Masset Band. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- The Hydah mission, Queen Charlotte's Islands : an account of the mission and people, with a descriptive letter, Rev. Charles Harrison, publ. Church Missionary Society/Seeley, Jackson & Halliday, London, England, 1884.

- Yahgulanaas, Michael Nicoll (2008) "Flight of the Hummingbird" Vancouver; Greystone Books.

Notes

- ↑ Ethnologue. (2005). "Language Family Trees: Na-Dene, Haida." In Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th ed. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Online (2007). Retrieved on 2007-06-01. Follow links for ethnic population figures, as follows: Northern Haida—1,700 (1,100 in Canada, 600 in US); Southern Haida—500 (all in Canada).

- ↑ Schoonmaker, Peter K.; Bettina Von Hagen, Edward C. Wolf (1997). The Rain Forests of Home: Profile Of A North American Bioregion. Island Press. pp. 257. ISBN 1559634804.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Warfare". Canadian Museum of Civilization. http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/haida/havwa01e.shtml. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Elms p 20, citing William Wyford Walkem, Stories of Early British Columbia, "Adam Horne's trip across Vancouver Island" (Vancouver, BC: Published by News Advertiser, 1914) p 41.

- ↑ Beth Gibson, Beheaded Pioneer, Laura Arksey, Columbia, Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, Spring, 1988.

- ↑ Bancroft says they were Stikines, a Tlingit subgroup, and makes no mention of the Haida. History of Washington, Idaho, and Montana : 1845-1889, p.137 Hubert Howe Bancroft (1890)

- ↑ Canadian Museum of Civilization webpage on Haida villages

- ↑ Parks Canada website

References

- Macnair, Peter L.; Hoover, Alan L.; Neary, Kevin (1981) The Legacy – Continuing Traditions of Canadian Northwest Coast Indian Art