Lidice

| Lidice | |

| Village | |

|

Museum

|

|

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Region | Central Bohemian |

| District | Kladno |

| Little District | Kladno |

| Elevation | 343 m (1,125 ft) |

| Coordinates | |

| Area | 4.74 km² (1.83 sq mi) |

| Population | 435 (As of 2006[update]) |

| Density | 92 / km² (238 / sq mi) |

| First mentioned | 1318 |

| Mayor | Václav Zelenka |

| Postal code | 273 54 |

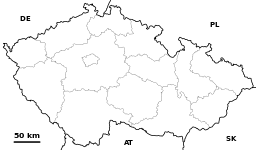

Location in the Czech Republic

|

|

| Wikimedia Commons: Lidice | |

| Website: www.obec-lidice.cz | |

Lidice (German: Liditz) is a village in the Czech Republic just north-west of Prague. It is built on the site of a previous village of the same name which, as part of the Nazi created Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, was, as per orders directly from Heinrich Himmler, completely destroyed by German forces in reprisal for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in the late spring of 1942. On June 10, 1942, all 192 men over 16 years of age from the village were murdered on the spot by the Germans in a much publicised atrocity. The rest of the population were sent to Nazi concentration camps where many women and nearly all the children were killed.

Contents |

History

The village is first mentioned in writing in 1318. After the industrialization of the area, many of its people worked in mines and factories in the neighboring cities of Kladno and Slaný.

Heydrich's assassination

In 1942, Reinhard Heydrich was the deputy Reichsprotektor of the Nazi German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. This area of the former Czechoslovakia had been occupied by Germany since 1939.

On the morning of May 27, 1942, Heydrich was being driven from his country villa at Panenské Břežany to his office at Prague Castle. When he reached the Holešovice area of Prague, his car was attacked by two Czechoslovak resistance fighters, Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš. These men, who had been trained in Great Britain, had parachuted into Bohemia in December 1941 as part of Operation Anthropoid. After Gabčík's Sten gun failed, Kubiš threw a bomb at Heydrich's car. Both parachutists managed to escape the scene of the assassination. On June 4, Heydrich died in Bulovka hospital in Prague from septicaemia caused by pieces of upholstery entering his body when the bomb exploded. Adolf Hitler ordered Kurt Daluege, Heydrich's successor, to `wade through blood` to find Heydrich's killers. The Germans began a massive and bloody retaliation campaign targeting the entire Czech population.

The mourning speeches at Heydrich's funeral in Berlin were not yet over, when on June 9 the decision was made to "make up for his death". Karl Hermann Frank, Secretary of State for the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, reported from Berlin that the Führer had commanded the following concerning any village found to have harboured Heydrich's killers:

- Execute all adult men

- Transport all women to a concentration camp

- Gather the children suitable for Germanization, then place them in SS families in the Reich and bring the rest of the children up in other ways

- Burn down the village and level it entirely

Massacre

Horst Böhme, SS Commander of the C division of the Einsatzgruppe, acted on the commands immediately. Members of the German Army field police and SD (Sicherheitsdienst) surrounded the village of Lidice, blocking all avenues of escape. The Nazi regime chose this village because of its residents' known hostility to the occupation, and because Lidice was suspected of harboring local resistance partisans.

All men of the village were rounded up and taken to the farmstead of the Horák family on the edge of the village. Mattresses were taken from neighbouring houses where they were stood up against the wall of the Horáks' barn. Shooting of the men commenced at about 7 a.m. At first the men were shot in groups of five, but Böhme thought the executions were proceeding too slowly and ordered that ten men be shot at a time. The dead were left lying where they fell and the newly brought out soon-to-be victims had to first walk past them and stand in front of them. The firing squad always took two steps back and the scene of horror repeated itself. The men were not blindfolded and were taken to the place of execution without bonds. This spectacle continued until the afternoon hours when there were 173 dead bodies lying in the Horák farm orchard. The next day, another nineteen men who had been working in a mine, along with seven women, were sent to Prague, where they were also shot.

All the women and children of the village were taken first to Lidice village school. They were then taken to the nearby town of Kladno where they were detained in the grammar school for three days. The children were then forcibly separated from their mothers. Four women were pregnant and were sent to the same hospital where Heydrich died. They were given forced abortions and then sent to different concentration camps. 184 women of Lidice were loaded on trucks on June 12, 1942, driven to Kladno railway station and forced into a special passenger train guarded by a large escort. In the morning of June 14, 1942 the train halted in the railway siding where it was met by several dozen armed women warders with dogs. Under constant shouting and verbal abuse, the Lidice women had reached their destination at the concentration camp at Ravensbrück. On their arrival the Lidice women were first isolated in a special block. The women were involved in leather processing, road building, textile and ammunition factories. At the ammunition factory the slightest offense was punishable by standing and starving for many hours, or being immersed in ice-cold water. Lack of hygiene, epidemics and contagious diseases spread and took most of the women. Some went mad and others were murdered.

Eighty-eight Lidice children were transported to the area of the former textile factory in Gneisenaustreet of Łódź. Their arrival was announced by a telegram from Horst Böhme's Prague office which ended with, the children are only bringing what they wear. No special care is desirable. The care was minimal. The children were not fed sufficiently and a few babies cared for by the older girls were constantly crying with hunger. The children slept on plain floors and covered themselves with coats if they had any brought from home. They suffered from a lack of hygiene and from illnesses. Under commands from the camp management, no medical care was given to the children. Shortly after their arrival in Łódź, officials from the Central Race and Settlement branch chose seven children at random for Germanisation.[1]

The furor over Lidice caused some hesitation over the fate of the remaining children,[1] but in late June Adolf Eichmann ordered the massacre of the remainder of the children. On July 1, 1942 the Lidice children were allowed to write postcards to their relatives. On July 2, 1942 all of the remaining 81 Lidice children were handed over to the Łódź Gestapo office, who in turn had them transported to the extermination camp at Chełmno 70 kilometres away, where they were gassed to death in Magirus gas vans. It is almost certain they were killed on the day of their arrival. Out of the 105 Lidice children, 82 died in Chełmno, six died in the German Lebensborn orphanages and 17 returned back home.

The village of Lidice was set on fire and the remains of the buildings were bulldozed, every last remaining piece of evidence being destroyed. Even those buried in the town cemetery were not spared. Their remains were dug up and destroyed. A film was made of the entire process by Franz Treml. A collaborator with German intelligence, Treml had run a Zeiss-Ikon shop in Lucerna Palace in Prague. After the German occupation he became a filming adviser for the National Socialist German Workers Party.

Altogether, about 340 people from Lidice died because of the German reprisal (192 men, 60 women and 88 children).

A small Czech village called Ležáky was also destroyed two weeks after Lidice. Here both men and women were shot, and children were sent to concentration camps or 'Aryanised'.

The death toll resulting from the effort to avenge the death of Heydrich is estimated at 1,300. This count includes relatives of the partisans, their supporters, Czech elites suspected of disloyalty and random victims like those from Lidice.

Nazi propaganda had openly, and proudly, announced the events in Lidice, unlike other massacres in occupied Europe which were kept secret. The information was instantly picked up by Allied media.

Commemorations

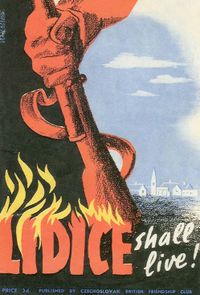

In September 1942, coal miners in Stoke-on-Trent in Great Britain founded the organisation Lidice Shall Live to raise funds for the rebuilding of the village after the war.[2]

Soon after the razing of the village, several towns in various countries were named after it (such as San Jerónimo-Lídice in Mexico City, Barrio Lídice and its hospital in Caracas, Venezuela, Lídice de Capira in Panama, and towns in Brazil), so that the name would live on in spite of Hitler's intentions. A neighborhood in Crest Hill, Illinois, was renamed from Stern Park to Lidice. A square in the English city of Coventry, itself devastated during World War II, is named after Lidice. An alley in downtown Santiago, Chile is named after the town of Lidice. A street in Sofia is named to commemorate the massacre.

In the wake of the massacre, Humphrey Jennings directed a movie about Lidice, The Silent Village (1943), using amateur actors from a Welsh mining village, Cwmgiedd. An American film was made in 1943 called Hitler's Madman, however it contained a number of inaccuracies in the story. A more accurate UK film, Operation Daybreak, starring Timothy Bottoms as Kubis and Anthony Andrews as Gabcík, was released in 1976.

American poet Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote a book-length verse play on the massacre, The Murder of Lidice that was printed in its entirety in the Oct. 19, 1942, edition of Life magazine and published as a book that same year by Harper.[3]

Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů composed his Memorial to Lidice (an 8-minute orchestral work full of grief and despair) in 1943 as a response to the massacre. The piece quotes from the Czech St Wenceslas Chorale, as well as, in the central climax of the piece, the opening notes (dot-dot-dot-dash = V in Morse code) of Beethoven's 5th Symphony.[4]

Lidice since 1945

Women from Lidice who survived imprisonment at Ravensbrück returned after the Second World War. They were re-housed in a new village of Lidice that was built overlooking the original site. The first part of the new village was completed in 1949.

Two men from Lidice were in the United Kingdom serving in the Royal Air Force at the time of the massacre. After 1945 Pilot Officer Josef Horák and Flight Lieutenant Josef Stříbrný returned to Czechoslovakia to serve in the Czechoslovak Air Force. However, after the Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948 the new Communist government would not allow them to apply to be housed in the new Lidice because they had served in the forces of one of the western powers. Horák and his family returned to Britain and the RAF but was killed in a flying accident in December 1948.[5]

A sculpture from the 1990s by academic sculptor Marie Uchytilová stands today overlooking the site of the old village of Lidice. Entitled "The Memorial to the Children Victims of the War" it comprises 82 bronze statues of children (42 girls and 40 boys) aged 1 to 16 to honour the children who were murdered at Chełmno in summer 1942. A cross with a crown of thorns marks the mass grave of the Lidice men. Overlooking the site is a "pious area" flanked by museum and a small exhibition hall.[1] The pious area is linked to the new village by an avenue of linden trees. In 1955 a "Rosarium" of 29,000 rose bushes was created beside the avenue of lindens overlooking the site of the old village. In the 1990s the Rosarium was neglected, but after 2001 a new Rosarium with 21,000 bushes was designed and created.[6] Situated 500 metres from the museum, in the new village, there is an art gallery which displays permanent and temporary exhibitions. The annual children's art competition attracts entries worldwide.

Sister cities

Khojaly (2010)[7]

Khojaly (2010)[7]

See also

- Collective punishment

- Operation Kutschera

- List of massacres

- Reprisal

- Sir Barnett Stross

- Lou Kenton

- Khatyn massacre

- German war crimes

- Oradour-sur-Glane

- Postoloprty

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p 254 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ↑ "Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 8". February 22, 1946

- ↑ Millay, Edna St. Vincent. The Murder of Lidice. New York: Harper: 1942.

- ↑ Mihule J. Liner note to Supraphon CD 11 1931-2 001, which includes the work played by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Karel Ančerl.

- ↑ David Vaughan. "Josef Horak, a twentieth century Czech hero". Český Rozhlas. July 24, 2002.

- ↑ "The History of Lidice Memorial Before Year 2000". Lidice Memorial.

- ↑ "A street in Lidice, Czechia to be named after Khojaly". APA. February 9, 2010.

Books

- Joan M. Wolf: Someone Named Eva. 2007. ISBN 0618535799

- Eduard Stehlík: Lidice, The Story of a Czech Village. 2004. ISBN 8086758141

- Zena Irma Trinka: A little village called Lidice: Story of the return of the women and children of Lidice. International Book Publishers, Western Office, Lidgerwood, North Dakota, 1947.

External links

- The Silent Village at the Internet Movie Database - The true story of the massacre of a small Czech village by the Nazis is retold as if it happened in Wales.

- Alan Heath : Fate of the children of Lidice

- (English) (Czech) (German) (Russian) Lidice Memorial

- (Czech) Official Website of Municipality

- (Czech) Recent (since 1990s) search for missing children

- (Czech) Photo series about destruction of Lidice by Reichsarbeitsdienst

|

|||||