MESSENGER

Technicians prepare MESSENGER for transfer to a hazardous processing facility prior to loading the spacecraft's complement of hypergolic propellants. |

|

| Operator | NASA |

|---|---|

| Major contractors | Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL) |

| Mission type | Fly-by(s)/orbit |

| Flyby of | Earth, Venus, Mercury |

| Satellite of | Mercury |

| Orbital insertion date | ETA: 2011-03-18 02:14:00 UTC |

| Launch date | 2004-08-03 06:15:56 UTC elapsed: 6 years, 6 months, and 11 days |

| Launch vehicle | Delta II 7925H-9.5 |

| Launch site | Space Launch Complex 17-A Cape Canaveral Air Force Station |

| COSPAR ID | 2004-030A |

| Homepage | messenger.jhuapl.edu |

| Mass | 1,093 kg (2,410 lb) |

| Power | 450 W (Mercury orbit nominal) |

The MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) probe is a NASA spacecraft, launched August 3, 2004 to study the characteristics and environment of Mercury from orbit. Specifically, the mission is to characterize the chemical composition of Mercury's surface, the geologic history, the nature of the magnetic field, the size and state of the core, the volatile inventory at the poles, and the nature of Mercury's exosphere and magnetosphere over a nominal orbital mission of one Earth year.

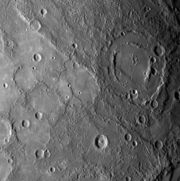

The mission is the first to visit Mercury in over 30 years; the only previous probe to visit Mercury was Mariner 10, which completed its mission in March 1975. The MESSENGER has vastly improved scanning capability, with cameras capable of resolving surface features to 18 m (59 ft) across compared to the 1.6 km (0.99 mi) resolution of the Mariner 10. MESSENGER is an orbital mission, and will spend over a year imaging the entire planet; Mariner 10 was a flyby mission and was only able to observe the one hemisphere that was lit during its flybys.

The contrived acronym MESSENGER was chosen because Mercury was the messenger of the gods according to Roman mythology.

Contents |

Travel to Mercury

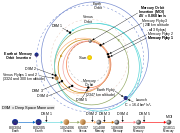

The Boeing Delta II rocket carrying MESSENGER lifted off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida at 02:15:56 EDT on August 3, 2004. An hour later, NASA confirmed that MESSENGER had successfully separated from the third stage booster and commenced its roundabout route to Mercury.

Travel to Mercury requires an extremely large velocity change, or delta-v, because Mercury lies deeper in the Sun's gravity well; a spacecraft traveling to Mercury is greatly accelerated as it falls toward the Sun, so there must be a mechanism to slow it. Mercury does not have an atmosphere thick enough to aerobrake on arrival. To make the trip feasible, MESSENGER makes extensive use of gravity assist maneuvers. These reduce the amount of rocket fuel needed to slow down, but greatly prolong the trip. For additional fuel savings, the thrust used for insertion into orbit about Mercury will be minimized, resulting in a notably elliptical orbit. Besides the advantage of saving fuel, such an orbit allows the spacecraft to measure solar wind and magnetic fields at a variety of distances from the planet, yet still get close-up measurements and photographs of the surface.

MESSENGER performed a successful Earth swing-by a year after launch, on 2 August 2005, with the closest approach at 19:13 UTC at an altitude of 2,347 kilometers (1,458 statute miles) over central Mongolia. On December 12, 2005, a 524 second long burn (Deep-Space Maneuver or DSM-1) of the large thruster adjusted the trajectory for the upcoming Venus swing-by.[1]

MESSENGER made its first flyby of Venus at 08:34 UTC on October 24, 2006 at an altitude of 2,992 kilometers (1,859 mi). A second flyby of Venus was made at 23:08 UTC on June 5, 2007 at an altitude of 338 kilometers (210 mi). On October 17, 2007, Deep-Space Maneuver 2 or DSM-2' was executed successfully, putting MESSENGER on target for its first flyby of Mercury.[2] MESSENGER made a flyby of Mercury on 14 January 2008 (closest approach 200 km above surface of Mercury at 19:04:39 UTC), followed by a second flyby on October 6, 2008.[3] MESSENGER executed one last flyby on September 29, 2009, that further slowed down the spacecraft. Both the second and third flybys were preceded by DSM-3 on 19 March 2008 at 19:30 UTC and DSM-4 on 04 Dececember, 2008 at 20:30 UTC to adjust the velocity of the spacecraft.[4][5] One last deep space maneuver, DSM-5 was executed on November 24, 2009 at 22:45 UTC to provide the required velocity change for the scheduled Mercury orbit insertion on March 18, 2011, marking the beginning of a year-long orbital mission.[6]

All along the way, numerous trajectory corrections were made to MESSENGER's course. The corrections numbered 35 as of 24, November 2009 and are referred to as TCM or Trajectory Correction Maneuver. TCM which use the large bi-propellant thrusters are also referred to as DSM or Deep Space Maneuver. DSM generally concern major ajustments to the spacecraft's velocity while TCM usually deal with modifying the craft's orientation with respect to the sun (crucial for thermal management) and targeting aim points for flybys of planets.[7]

During the Earth flyby, MESSENGER imaged the Earth and Moon and used its atmospheric and surface composition spectrometer to look at the Moon. The particle and magnetic field instruments investigated the Earth's magnetosphere.

The spacecraft was originally scheduled to launch during a 12-day window that opened May 11, 2004, but on March 26, 2004, NASA announced that a later launch window starting at July 30, 2004 with a length of 15 days would be used. This was to allow more time for testing and spacecraft processing.[8] This change significantly altered the trajectory of the mission and delayed the arrival at Mercury by two years. The original plan called for three fly-by maneuvers past Venus, with Mercury orbit insertion scheduled for 2009. The new trajectory features one Earth flyby, two Venus flybys, and three Mercury flybys before orbit insertion on March 18, 2011.

The navigation team is led by KinetX, Inc. of Tempe, AZ. KinetX is the first private company to be responsible for navigation of a NASA deep space mission. In that role, they are responsible for determining all trajectory adjustments throughout the probe's flight through the inner solar system ensuring that MESSENGER arrives at Mercury with the proper velocity for orbit insertion.

Mercury observation plan

The nominal orbit has a periapsis of 200 km (120 mi) at 60 degrees N latitude, and an apoapsis of 15,193 km (9,440 mi), a period of 12 hours and an inclination of 82.5 degrees. The periapsis will slowly rise due to solar perturbations to over 400 km (250 mi) at the end of 88 days (one Mercury year) at which point it will be readjusted to a 200 km (120 mi), 12 hour orbit via a two burn sequence.[9] Data will be collected from orbit for one Earth year, the nominal end of the primary mission. Global stereo image coverage at 250 meters/pixel resolution is expected. The mission should also yield global composition maps, a 3-D model of Mercury's magnetosphere, topographic profiles of the northern hemisphere, gravity field to degree and order 16, altitude profiles of elemental species, and a characterization of the volatiles in permanently shadowed craters at the poles.

Once there, scientists hope to test a theory that the planet is shrinking, contracting on itself as its core slowly freezes. The probe will look for signs of surface buckling on Mercury's unobserved hemisphere, as well as collect surface composition data on material that may have once spewed out of the planet's interior. The idea that Mercury's surface was somehow shrinking arose when Mariner 10 returned images of great scarps biting deep into the planet's surface. One such scarp, Discovery Rupes, cuts 1.6 km (1 mi) into Mercury's crust.

Spacecraft and subsystems

MESSENGER was designed and built by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL). It is a squat box (1.27 m × 1.42 m × 1.85 m) with a semi-cylindrical thermal shade for protection from the Sun and two solar panel wings extending radially. A 3.6 m (12 ft) magnetometer boom also extends from the craft. The total mass of the spacecraft is 1,093 kg (2,410 lb); 607.8 kg (1,340 lb) of this is propellant (hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide) and helium. The structure is primarily graphite cyanate ester (GrCE) composite and consists of two vertical panels which support two large fuel tanks and two vertical panels which support the oxidizer tank and plumbing panel. The four vertical panels make up the center column and are bolted at their aft ends to an aluminum adapter. A single top deck panel mounts the LVA (large velocity adjust) thruster, small thrusters, helium and auxiliary fuel tanks, star trackers and battery.

Main propulsion is via the 645 N (145 lbf), 317 s bipropellant LVA thruster. Four 22 N (4.9 lbf) monopropellant thrusters provide spacecraft steering during main thruster burns, and ten 4 N (0.9 lbf) monopropellant thrusters are used for attitude control. There is also a reaction wheel attitude control system. Information for attitude control is provided by star tracking cameras, an inertial measurement unit, and six solar sensors. Power is provided by solar panels which extend beyond the sunshade. They are rotatable to balance panel temperature and power generation and provide a nominal 450 watts in Mercury orbit. The panels are 70 percent optical solar reflectors and 30 percent GaAs/Ge cells. The power is stored in a common-pressure-vessel, 23-ampere-hour nickel hydrogen battery, with 11 vessels and two cells per vessel.

Communications uses two small deep space transponders (SDSTs) operating at X-band. Downlink is through two fixed phased array antenna clusters, and uplink and downlink through medium- and low-gain antennas on the forward and aft sides of the spacecraft. Passive thermal control, primarily a fixed opaque ceramic cloth sunshade, is utilized to maintain operating temperatures near the Sun. Radiators are built into the structure and the orbit is optimized to minimize infrared and visible light heating of the spacecraft from the surface of Mercury. Multilayer insulation, low conductivity couplings, and heaters are also used to maintain temperatures within operating limits.

Five science instruments are mounted externally on the bottom deck of the main body: the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer (GRNS), X-ray Spectrometer (XRS), Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA), and Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer (MASCS). The Energetic Particle and Plasma Spectrometer (EPPS) is mounted on the side and top deck and the magnetometer (MAG) is at the end of the 3.6 meter boom. Radio Science (RS) experiments will use the existing communications system (see:Radio Science Subsystem).

MESSENGER's onboard computer system is based on the Integrated Electronics Module (IEM), a device that combines core avionics in a single box. The spacecraft carries a pair of identical IEMs for backup purposes; both house a 25 megahertz main processor and 10 MHz fault protection processor. All four are radiation-hardened IBM RAD6000 processors, based on the IBM POWER1 CPU architecture (similar to that of older Macintoshes). The RAD computer is slow by current personal computer standards, but is capable of radiation tolerance required on the MESSENGER mission. For data storage, the spacecraft carries two solid-state recorders (one backup) able to store up to one gigabyte each. Its main processor collects, compresses, and stores on the recorder images and other data from MESSENGER's instruments, which can then be sent back to Earth.

Scientific results

MESSENGER performed its first Mercury flyby successfully on 14 January 2008, and its second flyby on 6 October 2008, taking pictures with both the wide angle and narrow angle cameras as well as using some of its other sensors. Preliminary image results from this first pass can be viewed at JHUAPL's MESSENGER Science Photos page.

On July 3, 2008, MESSENGER team member Thomas Zurbuchen announced that the probe discovered large amounts of water present in Mercury's exosphere. "Nobody expected that. I don't know a single person that did. We were astonished, just astonished," Zurbuchen stated.[10]

MESSENGER also provided visual evidence of volcanic activity on the surface of Mercury as well as evidence for a liquid planetary core.[10]

MESSENGER performed its third and last Mercury flyby on September 29, 2009 with the spacecraft coming within 142 mi (229 km) of the planet's surface. The inbound portion of the fly-by seems to have gone as planned, however sometime during the closest approach the spacecraft entered safe mode. Although this had no effect on the trajectory necessary for later orbit insertion it may have resulted in the loss of science data and images that were planned for the outbound leg of the fly-by. The spacecraft had fully recovered by about 7 hours later.[11]

References

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University (12 December 2005). "MESSENGER Engine Burn Puts Spacecraft on Track for Venus". Press release. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=18956. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University (17 October 2007). "Critical Deep-Space Maneuver Targets MESSENGER for Its First Mercury Encounter". Press release. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/2007/status_report_10_17_07.html. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University (14 January 2008). "Countdown to MESSENGER's Closest Approach with Mercury". Press release. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/gallery/sciencePhotos/image.php?gallery_id=2&image_id=115. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University (19 March 2008). "Critical Deep-Space Maneuver Targets MESSENGER for Its Second Mercury Encounter". Press release. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/details.php?id=96. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University (4 December 2008). "Deep-Space Maneuver Positions MESSENGER for Third Mercury Encounter". Press release. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/details.php?id=116. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University (24 November 2009). "Deep-Space Maneuver Positions MESSENGER for Mercury Orbit Insertion". Press release. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/details.php?id=140. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ Mission Design: Trajectory Correction Maneuvers, Johns Hopkins University, http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/maneuvers.html, retrieved 2010-04-20

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University (2004-03-24). "MESSENGER Launch Rescheduled.". Press release. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/2004/status_report_03_24_04.html. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ "MESSENGER Mission Design: Working from Orbit". Johns Hopkins University. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/orbit.html. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Emily Lakdawalla (3 July 2008). "MESSENGER Scientists 'Astonished' to Find Water in Mercury's Thin Atmosphere". The Planetary Society. http://www.planetary.org/news/2008/0703_MESSENGER_Scientists_Astonished_to.html. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ "MESSENGER Gains Critical Gravity Assist for Mercury Orbital Observations". MESSENGER Mission News. September 30, 2009. http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/details.php?id=136. Retrieved 2009-09-30.

External links

- JHUAPL homepage - official site.

- MESSENGER Mission Page - official information regarding the mission on the nasa.gov website.

- MESSENGER Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Mercury Flyby 1 Visualization Tool - see simulated views of the instrument observations planned during the flyby.

- Mercury Flyby 1 Actuals - compares the simulated views to the images actually acquired by MESSENGER during flyby 1

- Mercury Flyby 2 Visualization Tool - a simulation of what MESSENGER does on this historic flyby.

- Mercury Flyby 2 Actuals - compares the simulated views to the images actually acquired by MESSENGER during flyby 2

- MESSENGER Image Gallery - Check the latest Images from MESSENGER.

- NSSDC Master Catalog entry.

- Video from MESSENGER as it departs Earth.

- Mercury Data Collected by both Mariner 10 and MESSENGER.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||