Mead

Mead (pronounced /ˈmiːd/ meed) or honey wine is an alcoholic beverage, made from honey and water via fermentation with yeast. Its alcoholic content may range from that of a mild ale to that of a strong wine. It may be still, carbonated, or sparkling; it may be dry, semi-sweet, or sweet.[1]

Depending on local traditions and specific recipes, it may be brewed with spices, fruits, or grain mash. It may be produced by fermentation of honey with grain mash;[2] mead may also be flavored with hops[3] to produce a bitter, beer-like flavor.

Mead is independently multicultural. It is known from many sources of ancient history throughout Europe, Africa and Asia, although archaeological evidence of it is ambiguous.[4] Its origins are lost in prehistory; "it can be regarded as the ancestor of all fermented drinks," Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat has observed, "antedating the cultivation of the soil."[5] Claude Lévi-Strauss makes a case for the invention of mead as a marker of the passage "from nature to culture."[6]

Contents |

History

The earliest archaeological evidence for the production of mead dates to around 7000 BC. Pottery vessels containing a mixture of mead, rice and other fruits along with organic compounds of fermentation were found in Northern China.[7] In Europe, it is first attested in residual samples found in the characteristic ceramics of the Bell Beaker Culture.

The earliest surviving description of mead is in the hymns of the Rigveda,[8] one of the sacred books of the historical Vedic religion and (later) Hinduism dated around 1700–1100 BC. During the Golden Age of Ancient Greece, mead was said to be the preferred drink.[9] Aristotle (384–322 BC) discussed mead in his Meteorologica and elsewhere, while Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79) called mead militites in his Naturalis Historia and differentiated wine sweetened with honey or "honey-wine" from mead.[10] The Spanish-Roman naturalist Columella gave a recipe for mead in De re rustica, about AD 60.

Around AD 550, the Brythonic speaking bard Taliesin wrote the Kanu y med or "Song of Mead."[11] The legendary drinking, feasting and boasting of warriors in the mead hall is echoed in the mead hall Dyn Eidyn (modern day Edinburgh), and in the epic poem Y Gododdin, both dated around AD 700. In the Old English epic poem Beowulf, the Danish warriors drank Honey mead. Mead was the historical beverage par excellence and commonly brewed by the Germanic tribes in Northern Europe. Later, heavy taxation and regulations governing the ingredients of alcoholic beverages led to commercial mead becoming a more obscure beverage until recently.[12] Some monasteries kept up the old traditions of mead-making as a by-product of beekeeping, especially in areas where grapes could not be grown.

Etymology

The English word mead derives from the Old English medu, from Proto-Germanic meduz. Slavic med / miod , which means both "honey" and "mead", (Slovak, Serbian, Macedonian, Croatian: med vs. medovina, Polish 'miód' pronounce [mju:t] - honey, mead) and Baltic midus, which means "mead", also derive from the same Proto-Indo-European root (cf. Welsh medd, Old Irish mid, and Sanskrit madhu).[13]

Distribution

Mead was also popular in Central Europe and in the Baltic states. In the Polish language mead is called miód pitny ([ˈmiut ˈpitnɨ]), meaning "drinkable honey". In Russia mead remained popular as medovukha and sbiten long after its decline in the West. Sbiten is often mentioned in the works of 19th-century Russian writers, including Gogol, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy.

In Finland a sweet mead called Sima (cognate with zymurgy) is still an essential seasonal brew connected with the Finnish Vappu (May Day) festival. It is usually spiced by adding both the pulp and rind of a lemon. During secondary fermentation, raisins are added to control the amount of sugars and to act as an indicator of readiness for consumption; they will rise to the top of the bottle when the drink is ready.

Ethiopian mead is called tej (ጠጅ, IPA: [ˈtʼədʒ]) and is usually home-made. It is flavored with the powdered leaves and bark of gesho, a hop-like bittering agent which is a species of buckthorn. A sweeter, less-alcoholic version called berz, aged for a shorter time, is also made. The traditional vessel for drinking tej is a rounded vase-shaped container called a berele.

Mead known as iQhilika is traditionally prepared by the Xhosa of South Africa.

Varieties

Mead can have a wide range of flavors, depending on the source of the honey, additives (also known as "adjuncts" or "gruit"), including fruit and spices, the yeast employed during fermentation, and aging procedure. Mead can be difficult to find commercially. Some producers have marketed white wine with added honey as mead, often spelling it "meade." This is closer in style to a Hypocras. Blended varieties of mead may be known by either style represented. For instance, a mead made with cinnamon and apples may be referred to as either a cinnamon cyser or an apple metheglin.

A mead that also contains spices (such as cloves, cinnamon or nutmeg), or herbs (such as oregano, hops, or even lavender or chamomile), is called a metheglin (pronounced /mɨˈθɛɡlɪn/).[14][15]

A mead that contains fruit (such as raspberry, blackberry or strawberry) is called a melomel,[16] which was also used as a means of food preservation, keeping summer produce for the winter. A mead that is fermented with grape juice is called a pyment.[16]

Mulled mead is a popular drink at Christmas time, where mead is flavored with spices (and sometimes various fruits) and warmed, traditionally by having a hot poker plunged into it.

Some meads retain some measure of the sweetness of the original honey, and some may even be considered as dessert wines. Drier meads are also available, and some producers offer sparkling meads. There are a number of faux-meads, which are actually cheap wines with large amounts of honey added, to produce a cloyingly sweet liqueur.

Historically, meads were fermented by wild yeasts and bacteria (as noted in the below quoted recipe) residing on the skins of the fruit or within the honey itself. Wild yeasts generally provide inconsistent results, and in modern times various brewing interests have isolated the strains now in use. Certain strains have gradually become associated with certain styles of mead. Mostly, these are strains that are also used in beer or wine production. However, several commercial labs, such as White Labs, WYeast, Vierka, have developed yeast strains specifically for mead. Mead yeasts are better suited to preserve the delicate honey flavors than a wine or beer yeast.

Mead can be distilled to a brandy or liqueur strength. A version of this called "honey jack" can be made by partly freezing a quantity of mead and pouring off the liquid without the ice crystals (a process known as freeze distillation), in the same way that applejack is made from cider.

Mead variants

- Acan — A Native Mexican version of mead.

- Acerglyn — A mead made with honey and maple syrup.

- Bochet — A mead where the honey is caramelized or burned separately before adding the water. Gives toffee, chocolate, marshmallow flavors.

- Braggot — Braggot (also called bracket or brackett). Originally brewed with honey and hops, later with honey and malt — with or without hops added. Welsh origin (bragawd).

- Black mead — A name sometimes given to the blend of honey and blackcurrants.

- Capsicumel — A mead flavored with chile peppers.

- Chouchenn — A kind of mead made in Brittany.

- Cyser — A blend of honey and apple juice fermented together; see also cider.

- Czwórniak (TSG) — A Polish mead, made using three units of water for each unit of honey

- Dandaghare — A mead from Nepal, combines honey with Himalayan herbs and spices. It has been brewed since 1972 in the city of Pokhara.

- Dwójniak(TSG) — A Polish mead, made using equal amounts of water and honey

- Great mead — Any mead that is intended to be aged several years. The designation is meant to distinguish this type of mead from "short mead" (see below).

- Gverc or Medovina — Croatian mead prepared in Samobor and many other places. The word “gverc” or “gvirc” is from the German "Gewürze" and refers to various spices added to mead.

- Hydromel — Hydromel literally means "water-honey" in Greek. It is also the French name for mead. (Compare with the Spanish hidromiel and aquamiel, Italian idromele and Portuguese hidromel). It is also used as a name for a very light or low-alcohol mead.

- Medica — Slovenian, Croatian, variety of Mead.

- Medovina — Czech, Serbian, Bulgarian, Bosnian and Slovak for mead. Commercially available in Czech Republic, Slovakia and presumably other Central and Eastern European countries.

- Medovukha — Eastern Slavic variant (honey-based fermented drink).

- Myod — Traditional Russian mead, historically available in three major varieties: aged mead ("мёд ставленный") — a mixture of honey and water and/or (preferably) berry juices, subject to a very slow (12-50 years) anaerobic fermentation in airtight vessels in a process similar to the traditional balsamic vinegar, similarly creating very rich and complex, much praised, but extremely expensive product; drinking mead ("мёд питный") — a kind of honey wine made from diluted honey by traditional fermentation; and boiled mead ("мёд варёный") — a drink closer to beer, brewed from boiled wort of diluted honey and herbs, very similar to modern medovukha.

- Melomel — Melomel is made from honey and any fruit. Depending on the fruit-base used, certain melomels may also be known by more specific names (see cyser, pyment, morat for examples).

- Metheglin — Metheglin starts with traditional mead but has herbs and/or spices added. Some of the most common metheglins are ginger, tea, orange peel, nutmeg, coriander, cinnamon, cloves or vanilla. Its name indicates that many metheglins were originally employed as folk medicines. The Welsh word for mead is medd, and the word "metheglin" derives from meddyglyn, a compound of meddyg, "healing" + llyn, "liquor."

- Midus — Lithuanian for mead, made of natural bee honey and berry juice. Infused with carnation blossom, acorn, poplar buds, juniper berries and other herbs, it is often made as a mead distillate or mead nectar, some of the varieties having as much as 75% of alcohol.

- Morat — Morat blends honey and mulberries.

- Mulsum — Mulsum is not a true mead, but is unfermented honey blended with a high-alcohol wine.

- Omphacomel — A mediæval mead recipe that blends honey with verjuice; could therefore be considered a variety of pyment (qv).

- Oxymel — Another historical mead recipe, blending honey with wine vinegar.

- Pitarrilla — Mayan drink made from a fermented mixture of wild honey, balché tree bark and fresh water.

- Pyment — Pyment blends honey and red or white grapes. Pyment made with white grape juice is sometimes called "white mead."

- Półtorak(TSG) — A Polish great mead, made using two units of honey for each unit of water

- Rhodomel — Rhodomel is made from honey, rose hips, petals or rose attar and water.

- Sack mead — This refers to mead that is made with more copious amounts of honey than usual. The finished product retains an extremely high specific gravity and elevated levels of sweetness. It derives its name, according to one theory, from the fortified dessert wine Sherry (which is sometimes sweetened after fermentation and in England once bore the nickname of "sack");[17] another theory is that the term derived from the Japanese drink sake, being introduced by Spanish and Portuguese traders.[18]

- Short mead — Also called "quick mead." A type of mead recipe that is meant to age quickly, for immediate consumption. Because of the techniques used in its creation, short mead shares some qualities found in cider (or even light ale): primarily that it is effervescent, and often has a cidery taste. It can also be champagne-like.

- Show mead — A term which has come to mean "plain" mead: that which has honey and water as a base, with no fruits, spices or extra flavorings. Since honey alone often does not provide enough nourishment for the yeast to carry on its lifecycle, a mead that is devoid of fruit, etc. will sometimes require a special yeast nutrient and other enzymes to produce an acceptable finished product. In most competitions including all those using the BJCP style guidelines as well as the International Mead Fest, the term "traditional mead" is used for this variety. It should be considered, however, that since mead is historically a very variable product, such recent (and artificial) guidelines apply mainly to competition judging as a means of providing a common language; style guidelines, per se, do not really apply to commercial and historical examples of this or any type of mead.

- Sima - a quickly fermented low-alcoholic Finnish variety, seasoned with lemon and associated with the festival of vappu.

- Tej — Tej is an Ethiopian mead, fermented with wild yeasts (and bacteria), and with the addition of gesho. Recipes vary from family to family, with some recipes leaning towards braggot with the inclusion of grains.

- Trójniak(TSG) — A Polish mead, made using two units of water for each unit of honey.

- White mead — A mead that is colored white, either from herbs or fruit used or sometimes egg whites.

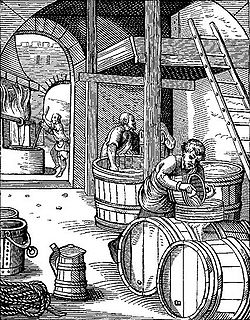

Recipes

| “ | Take of spring water what quantity you please, and make it more than blood-warm, and dissolve honey in it till 'tis strong enough to bear an egg, the breadth of a shilling; then boil it gently near an hour, taking off the scum as it rises; then put to about nine or ten gallons seven or eight large blades of mace, three nutmegs quartered, twenty cloves, three or four sticks of cinnamon, two or three roots of ginger, and a quarter of an ounce of Jamaica pepper; put these spices into the kettle to the honey and water, a whole lemon, with a sprig of sweet-briar and a sprig of rosemary; tie the briar and rosemary together, and when they have boiled a little while take them out and throw them away; but let your liquor stand on the spice in a clean earthen pot till the next day; then strain it into a vessel that is fit for it; put the spice in a bag, and hang it in the vessel, stop it, and at three months draw it into bottles. Be sure that 'tis fine when 'tis bottled; after 'tis bottled six weeks 'tis fit to drink.[19] | ” |

Festivals

- International Mead Festival — Sponsored by the International Mead Association, this festival is held every year often on the weekend closest to Valentine's Day in or near Boulder, Colorado. It claims to be the largest and most prestigious mead festival in the world. Both professional and home-brewed meads are judged.[20]

- Real Ale Festival in Chicago, Illinois, includes categories for mead as well as cider and perry.[21]

- Woodbridge International Mead Festival - Sponsored by local residents, it claims to be the only mead festival east of the Mississippi. While there are relatively few types of mead available, all are home-brewed and go through a rigorous judging process.

In literature

Mead features prominently in many Germanic myths and folktales such as Beowulf, and well as other popular in works that draw on these myths. Notable examples include books by Tolkien and Neil Gaiman. It is often featured in books using a historical Germanic setting, such as the viking era.

See also: Mead of Poetry (Norse mythology)

See also

- History of alcohol

- Mead hall

References

- ↑ Rose, Anthony H. (1977). Alcoholic Beverages. Michigan: Academic Press. pp. 413.

- ↑ Beer is produced by the fermentation of grain, but grain can be used in mead provided it is strained off immediately. As long as the primary substance fermented is still honey, the drink is still mead. Fitch, Edward (1989). Rites of Odin. St. Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn Worldwide. pp. 290. ISBN 0875422241, 9780875422244.

- ↑ Hops are better known as the bitter ingredient of beer. However, they have also been used in mead both anciently and in modern times. The Legend of Frithiof mentions hops: Mohnike, G.C.F. (September 1828 – January 1829). "Tegner's Legend of Frithiof". The Foreign Quarterly Review (Treuttel and Würtz, Treuttel, Jun and Richter) III. "He next ... bids ... Halfdan recollect ... that to produce mead hops must be mingled with the honey;". That this formula is still in use is shown by the recipe for "Real Monastery Mead" in Molokhovets, Elena; Joyce Stetson (Translator) (1998). Classic Russian Cooking. Indiana University Press. pp. 474. ISBN 0253212103, ISBN 9780253212708.

- ↑ Hornsey, Ian (2003). A History of Beer and Brewing. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 7. ISBN 9780854046300. "...mead was known in Europe long before wine, although archaeological evidence of it is rather ambiguous. This is principally because the confirmed presence of beeswax or certain types of pollen ... is only indicative of the presence of honey (which could have been used for sweetening some other drink) - not necessarily of the production of mead."

- ↑ Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat (Anthea Bell, tr.) The History of Food, 2nd ed. 2009:30.

- ↑ Lévi-Strauss, J. and D. Weightman, tr. From Honey to Ashes, London:Cape 1973 (Du miel aux cendres, Paris 1960)

- ↑ McGovern, PE; Zhang, J; Tang, J; Zhang, Z; Hall, GR; Moreau, RA; Nuñez, A; Butrym, ED et al. (December 6, 2004). "Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - Early Edition 101 (51): 17593–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. PMID 15590771. PMC 539767. http://www.pnas.org/content/101/51/17593.abstract?sid=0111bfc3-e87b-411a-b12c-8d99d0efbfd9.

- ↑ Rigveda Book 5 v. 43:3–4, Book 8 v. 5:6, etc

- ↑ Kerenyi, Karl (1976). Dionysus: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life. Princeton University Press. pp. 35. ISBN 0-691-09863-8.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. Natural History XIV. XII:85 etc.

- ↑ Llyfr Taliesin XIX

- ↑ Buhner, Stephen Harrod (1998). Sacred and Herbal Healing Beers: The Secrets of Ancient Fermentation. Siris Books. ISBN 0-937381-66-7.

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary entry for 'mead'

- ↑ Tayleur, W.H.T.; Michael Spink (1973). The Penguin Book of Home Brewing and Wine-Making. Penguin. pp. 292. ISBN 0140461906.

- ↑ Aylett, Mary. Country Wines, Odhams Press, 1953, p.79

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Tayleur, p.291

- ↑ Sack in the Oxford Companion to Wine

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Spencer, Edward (1903). The Flowing Bowl. pp. 32–33.

- ↑ International Mead Festival official website

- ↑ Real Ale Festival official website

Further reading

- Schramm, Ken (2003). The Compleat Meadmaker. Brewers Publications. ISBN 0-937381-82-9.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1976). Dionysus: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09863-8.

- Digby, Kenelm; Jane Stevenson, Peter Davidson (1997). The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kt Opened 1669. Prospect Books. ISBN 0-907325-76-9.

- Gayre, Robert; Papazian, Charlie (1986). Brewing Mead: Wassail! In Mazers of Mead. Brewers Publications. ISBN 0-937381-00-4.

External links

- Got Mead - Mead (honeywine) making, mead drinking, mead recipes

- Miod pitny - traditional Polish mead

- The Joy of Mead Mead Making Tutorial

- Mead Made Easy

- Washington Wine Maker A Simple Mead Recipe

- Barat's Mead Page Detailed step-by-step mead making instructions for beginner to intermediate mead makers

- FermentBrussels Experimental mead prepared only with ingredients found in the urban environment.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||