Measles

| Measles | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

|

|

| ICD-10 | B05. |

| ICD-9 | 055 |

| DiseasesDB | 7890 |

| MedlinePlus | 001569 |

| eMedicine | derm/259 emerg/389 ped/1388 |

| MeSH | D008457 |

| Measles virus | |

|---|---|

| Measles virus | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group V ((-)ssRNA) |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Paramyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Morbillivirus |

| Type species | |

| Measles virus |

|

Measles, also known as Rubeola, is an infection of the respiratory system caused by a virus, specifically a paramyxovirus of the genus Morbillivirus. Morbilliviruses, like other paramyxoviruses, are enveloped, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA viruses. Symptoms include fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes and a generalized, maculopapular, erythematous rash.

Measles (sometimes known as English Measles) is spread through respiration (contact with fluids from an infected person's nose and mouth, either directly or through aerosol transmission), and is highly contagious—90% of people without immunity sharing a house with an infected person will catch it. The infection has an average incubation period of 14 days (range 6–19 days) and infectivity lasts from 2–4 days prior, until 2–5 days following the onset of the rash (i.e. 4–9 days infectivity in total).[1]

An alternative name for measles in English-speaking countries is rubeola, which is sometimes confused with rubella (German measles); the diseases are unrelated.[2][3]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

The classical symptoms of measles include four day fevers, the three Cs—cough, coryza (runny nose) and conjunctivitis (red eyes). The fever may reach up to 40 °C (104 °F). Koplik's spots seen inside the mouth are pathognomonic (diagnostic) for measles but are not often seen, even in real cases of measles, because they are transient and may disappear within a day of arising.

The characteristic measles rash is classically described as a generalized, maculopapular, erythematous rash that begins several days after the fever starts. It starts on the head before spreading to cover most of the body, often causing itching. The rash is said to "stain", changing colour from red to dark brown, before disappearing.

Complications

Complications with measles are relatively common, ranging from relatively mild and less serious diarrhea, to pneumonia and encephalitis (subacute sclerosing panencephalitis), corneal ulceration leading to corneal scarring.[4] Complications are usually more severe amongst adults who catch the virus.

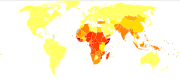

The fatality rate from measles for otherwise healthy people in developed countries is 3 deaths per thousand cases, or 0.3%.[5] In underdeveloped nations with high rates of malnutrition and poor healthcare, fatality rates have been as high as 28%.[5] In immunocompromised patients (e.g. people with AIDS) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.[6]

Cause

Patients with the measles should be placed on respiratory precautions.[7]

Humans are the only known natural host of measles, although the virus can infect some non-human primate species.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of measles requires a history of fever of at least three days together with at least one of the three C's (cough, coryza, conjunctivitis). Observation of Koplik's spots is also diagnostic of measles.

Alternatively, laboratory diagnosis of measles can be done with confirmation of positive measles IgM antibodies or isolation of measles virus RNA from respiratory specimens. In children, where phlebotomy is inappropriate, saliva can be collected for salivary measles specific IgA test. Positive contact with other patients known to have measles adds strong epidemiological evidence to the diagnosis. The contact with any infected person in any way, including semen through sex, saliva, or mucus can cause infection.

Prevention

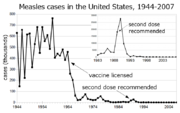

In developed countries, most children are immunized against measles by the age of 18 months, generally as part of a three-part MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella). The vaccination is generally not given earlier than this because children younger than 18 months usually retain anti-measles immunoglobulins (antibodies) transmitted from the mother during pregnancy. A second dose is usually given to children between the ages of four and five, in order to increase rates of immunity. Vaccination rates have been high enough to make measles relatively uncommon. Even a single case in a college dormitory or similar setting is often met with a local vaccination program, in case any of the people exposed are not already immune.

In developing countries where measles is highly endemic, the WHO recommend that two doses of vaccine be given at six months and at nine months of age. The vaccine should be given whether the child is HIV-infected or not.[8] The vaccine is less effective in HIV-infected infants, but the risk of adverse reactions is low.

Unvaccinated populations are at risk for the disease. After vaccination rates dropped in northern Nigeria in the early 2000s due to religious and political objections, the number of cases rose significantly, and hundreds of children died.[9]

In 1998 the MMR vaccine controversy in the United Kingdom regarding a potential link between the combined MMR vaccine (vaccinating children from mumps, measles and rubella) and autism prompted a reemergence of the "measles party", where parents deliberately expose their child to measles in the hope of building up the child's immunity without an injection. This practice poses many health risks to the child, and has been discouraged by the public health authorities.[10] Scientific evidence provides no support for the hypothesis that MMR plays a role in causing autism.[11] In 2009, The Sunday Times reported that Wakefield had manipulated patient data and misreported results in his 1998 paper, creating the appearance of a link with autism.[12] The Lancet fully retracted the 1998 paper on 2 February 2010.[13] In January 2010, another study of Polish children found that vaccination with the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine was not a risk factor for development of autistic disorder, in fact the vaccinated patients had a slightly reduced risk of autistic disorder, although the mechanism of action behind that is unknown, and this result may have been coincidental.[14]

The autism related MMR study in Britain caused use of the vaccine to plunge, and measles cases came back: 2007 saw 971 cases in England and Wales, the biggest rise in occurrence in measles cases since records began in 1995.[15] A 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana was attributed to children whose parents refused vaccination.[16]

The joint press release by members of the Measles Initiative brings to light another benefit of the fight against measles: "Measles vaccination campaigns are contributing to the reduction of child deaths from other causes. They have become a channel for the delivery of other life-saving interventions, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, de-worming medicine and vitamin A supplements. Combining measles immunization with other health interventions is a contribution to the achievement of Millennium Development Goal Number 4: a two-thirds reduction in child deaths between 1990 and 2015."[17]

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for measles. Most patients with uncomplicated measles will recover with rest and supportive treatment. It is, however, important to seek medical advice if the patient becomes more unwell as they may be developing complications.

Some patients will develop pneumonia as a sequel to the measles. Other complications include ear infections, bronchitis, and encephalitis. Acute measles encephalitis has a mortality rate of 15%. While there is no specific treatment for measles encephalitis, antibiotics are required for bacterial pneumonia, sinusitis, and bronchitis that can follow measles.

All other treatment is symptomatic, with ibuprofen, or acetaminophen (also called paracetamol) to reduce fever and pain and, if required, a fast-acting bronchodilator for cough. Note that young children should never be given aspirin without medical advice due to the risk of inducing a disease known as Reye's syndrome.

The use of Vitamin A in treatment has been investigated. A systematic review of trials into its use found no significant reduction in overall mortality, but that it did reduce mortality in children aged under 2 years.[18][19][20]

Prognosis

While the vast majority of patients survive measles, complications occur fairly frequently and may include bronchitis, pneumonia, otitis media, hemorrhagic complications, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, acute measles encephalitis, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (sspe), blindness, deafness, and death. Statistically out of 1000 measles cases, 2-3 patients die, and 5-105 suffer complications. In patients who do not develop complications, the prognosis is generally excellent. However, although most patients survive, it is still important to get vaccinated, as up to 15 percent of measles patients experience complications, some fairly mild, others (such as subacute sclerosing panencephalitis) typically fatal. Also, even if the patient is not concerned about death or sequela from the measles, the person may spread the disease to an immunocompromised patient, for whom the risk of death is much higher, due to complications such as giant cell pneumonia. Acute measles encephalitis is another serious risk of measles virus infection. It typically occurs 2 days to one week after the breakout of the measles exanthem, and begins with very high fever, severe headache, convulsions, and altered mentation. Patient may become comatose, and death or brain injury may occur.[21]

Epidemiology

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), measles is a leading cause of vaccine-preventable childhood mortality. Worldwide, the fatality rate has been significantly reduced by a vaccination campaign led by partners in the Measles Initiative: the American Red Cross, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Foundation, UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO). Globally, measles fell 60% from an estimated 873,000 deaths in 1999 to 345,000 in 2005.[17] Estimates for 2008 indicate deaths fell further to 164,000 globally, with 77% of the remaining measles deaths in 2008 occurring within the South-East Asian region.[22]

Five out of six WHO regions have set goals to eliminate measles, and at the 63rd World Health Assembly in May 2010, delegates agreed a global target of a 95% reduction in measles mortality by 2015 from the level seen in 2000, as well as to move towards eventual eradication. However, no specific global target date for eradication has yet been agreed as of May 2010.[23][24]

History and culture

History

The Antonine Plague, 165-180 AD, also known as the Plague of Galen, who described it, was probably smallpox or measles. Disease killed as much as one-third of the population in some areas, and decimated the Roman army.[25] The first scientific description of measles and its distinction from smallpox and chickenpox is credited to the Persian physician, Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi (860-932), known to the West as "Rhazes", who published a book entitled The Book of Smallpox and Measles (in Arabic: Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah).[26]

Measles is an endemic disease, meaning that it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations that have not been exposed to measles, exposure to a new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox. Two years later measles was responsible for the deaths of half the population of Honduras, and had ravaged Mexico, Central America, and the Inca civilization.[27]

In roughly the last 150 years, measles has been estimated to have killed about 200 million people worldwide.[28] During the 1850s, measles killed a fifth of Hawaii's people.[29] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[30] In the 19th century, the disease decimated the Andamanese population.[31] In 1954, the virus causing the disease was isolated from an 11-year old boy from the United States, David Edmonston, and adapted and propagated on chick embryo tissue culture.[32] To date, 21 strains of the measles virus have been identified.[33] While at Merck, Maurice Hilleman developed the first successful vaccine[34]. Licensed vaccines to prevent the disease became available in 1963.

Recent outbreaks

Since the beginning of September, 2009, Johannesburg, a city in Gauteng, South Africa reported about 48 cases of measles. Soon after the outbreak, the Government ordered that all children be vaccinated. Vaccination programs were then initiated in all schools and parents of young children were advised to have them vaccinated.[35] Many people were not willing to have the vaccination done, as it is believed to be unsafe and ineffective. The Health Department assured the public that their program was indeed safe. Speculation arose as to whether or not new needles were being used.[36] By mid-October there were at least 940 recorded cases, and 4 deaths.[37]

On February 19, 2009, 505 measles cases were reported in twelve provinces in the North of Vietnam, with Hanoi accounting for 160 cases.[38] A high rate of complications including meningitis & encephalitis has worried health workers[39] and the U.S. CDC recommended that all travelers be immune to measles.[40]

On The 1st of April 2009, an outbreak has happened in two schools in North Wales. Ysgol John Bright and Ysgol Ffordd Dyffryn in Wales have had the outbreak and are making sure every pupil has had the Measles vaccine.

In 2007, a large measles outbreak in Japan caused a number of universities and other institutions to close in an attempt to contain the disease.[41][42]

Approximately 1000 cases of the disease were reported in Israel between August 2007 and May 2008 (in sharp contrast to just some dozen cases the year before). Many children in ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities were affected due to low vaccination coverage.[43][44] As of 2008 the disease is endemic in the United Kingdom with 1,217 cases diagnosed in 2008 [45] and epidemics have been reported in Austria, Italy and Switzerland.[46]

In March 2010, Philippines declared an epidemic about the continuously rising cases of measles.

The Americas

Indigenous measles were declared to have been eliminated in North, Central, and South America; the last endemic case in the region was reported on November 12, 2002, with only Northern Argentina and rural Canada, particularly in the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta having minor endemic status.[47] Outbreaks are still occurring, however, following importations of measles viruses from other world regions. In June 2006, an outbreak in Boston resulted after a resident became infected in India,[48] and in October 2007, a Michigan girl who had been vaccinated contracted the disease in Sweden.[49]

Between January 1 and April 25, 2008, a total of 64 confirmed measles cases were preliminarily reported in the United States to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[50][51] the most reported by this date for any year since 2001. Of the 64 cases, 54 were associated with importation of measles from other countries into the United States, and 63 of the 64 patients were unvaccinated or had unknown or undocumented vaccination status.[52]

By July 9, 2008, a total of 127 cases were reported in 15 states (including 22 in Arizona),[53] making it the largest U.S. outbreak since 1997 (when 138 cases were reported).[54] Most of the cases were acquired outside of the United States and afflicted individuals who had not been vaccinated.

By July 30, 2008, the number of cases had grown to 131. Of these, about half involved children whose parents rejected vaccination. The 131 cases occurred in 7 different outbreaks. There were no deaths, and 15 hospitalizations. 11 of the cases had received at least one dose of the measles vaccine. 122 of the cases involved children who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown. Some of these were under the age of one year old and below the age when vaccination is recommended, but in 63 cases the vaccinations had been refused for religious or philosophical reasons.

Additional images

Intra oral rash of measles |

Measles in African Child |

This European child shows a classic day-4 rash with measles. |

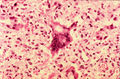

Histopathology of measles pneumonia. Giant cell |

See also

- Autism

- Infectious disease

- List of epidemics

- MMR vaccine

- Mumps

- Paramyxovirus

- Roseola ("baby measles")

- Rubella (German measles)

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

- Vaccine

References

- ↑ "Measles". http://www.patient.co.uk/showdoc/40000391/.

- ↑ Merriam-webster:Rubeola. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ T. E. C. Jr. Letters to the editor Pediatrics Vol. 49 No. 1 January 1972, pp. 150-151.

- ↑ Web.archive.org

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Perry, Robert T.; Halsey, Neal A. (May 1, 2004). "The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review". The Journal of Infectious Diseases (Infectious Diseases Society of America) 189 (S1): 1547–1783. doi:10.1086/377712. PMID 15106083. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/377712. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Sension, MG; Quinn, TC; Markowitz, LE; Linnan, MJ; Jones, TS; Francis, HL; Nzilambi, N; Duma, MN et al. (1988). "Measles in hospitalized African children with human immunodeficiency virus.". American journal of diseases of children (1960) 142 (12): 1271–2. PMID 3195521.

- ↑ Bekhor, D. Prevention and treatment of measles. in: UpToDate, Baslow, DS (ed.), Waltham, MA, 2009

- ↑ Helfand RF, Witte D, Fowlkes A, et al. (2008). "Evaluation of the immune response to a 2-dose measles vaccination schedule administered at 6 and 9 months of age to HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Malawi". J Infect Dis 198 (10): 1457–1465. doi:10.1086/592756. PMID 18828743.

- ↑ "Measles kills more than 500 children so far in 2005". IRIN. 2005-03-21. http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=53506. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ Dillner L (2001-07-26). "The return of the measles party". Guardian (London). http://lifeandhealth.guardian.co.uk/health/story/0,,1610704,00.html. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ Rutter M (2005). "Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning". Acta Paediatr 94 (1): 2–15. doi:10.1080/08035250410023124. PMID 15858952.

- ↑ Timesonline.co.uk

- ↑ NEWS.BBC.co.uk

- ↑ Reuters.com

- ↑ Torjesen I (2008-04-17). "Disease: a warning from history". Health Serv J: 22–4. PMID 18533314. http://www.hsj.co.uk/insideknowledge/features/2008/03/ingrid_torjesen_on_the_diseases_we_thought_had_gone_away.html.

- ↑ Parker A, Staggs W, Dayan G et al. (2006). "Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States". N Engl J Med 355 (5): 447–55. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060775. PMID 16885548.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 UNICEF Joint Press Release

- ↑ Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M (2005). "Vitamin A for treating measles in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD001479. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001479.pub3. PMID 16235283.

- ↑ D'Souza RM, D'Souza R (2002). "Vitamin A for treating measles in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001479. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001479. PMID 11869601.

- ↑ D'Souza RM, D'Souza R (April 2002). "Vitamin A for preventing secondary infections in children with measles--a systematic review". J. Trop. Pediatr. 48 (2): 72–7. doi:10.1093/tropej/48.2.72. PMID 12022432. http://tropej.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12022432.

- ↑ Merck.com

- ↑ WHO Weekly Epidemiology Record, 4th December 2009 WHO.int

- ↑ "Sixty-third World Health Assembly Agenda provisional agenda item 11.15 Global eradication of measles.". http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_18-en.pdf. Retrieved 02 June 2010.

- ↑ "Sixty-third World Health Assembly notes from day four". http://www.who.int/mediacentre/events/2010/wha63/journal4/en/index.html. Retrieved 02 June 2010.

- ↑ Plague in the Ancient World

- ↑ Harminder S. Dua, Ahmad Muneer Otri, Arun D. Singh (2008). "Abu Bakr Razi". British Journal of Ophthalmology (BMJ Group) 92: 1324.

- ↑ Mariner.org. Retrieved October 15, 2006.

- ↑ Torrey EF and Yolken RH. 2005. Their bugs are worse than their bite. Washington Post, April 3, p. B01.

- ↑ Migration and Disease. Digital History.

- ↑ Fiji School of Medicine

- ↑ Measles hits rare Andaman tribe. BBC News. May 16, 2006.

- ↑ "Live attenuated measles vaccine". EPI Newsl 2 (1): 6. 1980. PMID 12314356.

- ↑ Rima BK, Earle JA, Yeo RP, et al. (1995). "Temporal and geographical distribution of measles virus genotypes". J. Gen. Virol. 76 (5): 1173–80. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-76-5-1173. PMID 7730801. http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7730801.

- ↑ Offit PA (2007). Vaccinated: One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases. Washington, DC: Smithsonian. ISBN 0-06-122796-X.

- ↑ "Measles Outbreak In Joburg". http://www.news24.com/Content/SouthAfrica/News/1059/42cd42bfbe5545f8bccdfce63c0db184/29-09-2009-11-01/Measles_outbreak_in_Joburg.

- ↑ "Childhood Vaccinations Peak In 2009, But Uneven Distribution Persists". http://www.theinternationalonline.com/articles/98-childhood-vaccinations-peak-in-2009-but.

- ↑ "Measles Vaccination 'safe'". http://news24.com/Content/SouthAfrica/News/1059/54adfc32c0904c0ba92f92b021d68b3a/21-10-2009-11-27/Measles_vaccinations_safe.

- ↑ "Measles spreads to 12 provinces". Look At Vietnam. 20 February 2009. http://www.lookatvietnam.com/2009/02/measles-spreads-to-12-provinces.html.

- ↑ "Measles outbreak hits North Vietnam". Saigon Gia Phong. 4 February 2009. http://www.saigon-gpdaily.com.vn/Health/2009/2/68224/.

- ↑ AmCham Vietnam | Public Notice: Measles immunization recommendation

- ↑ "The Public Health Agency of Canada Travel Advisory". http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tmp-pmv/2007/measjap070601_e.html. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ Norrie, Justin (May 27, 2007). "Japanese measles epidemic brings campuses to standstill". The Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/japanese-measles-epidemic-brings-campuses-to-standstill/2007/05/27/1180205052602.html. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ Stein-Zamir, C.; G. Zentner, N. Abramson, H. Shoob, Y. Aboudy, L. Shulman and E. Mendelson (February 2008). "Measles outbreaks affecting children in Jewish ultra-orthodox communities in Jerusalem". Epidemiology and Infection 136 (2): 207–214. doi:10.1017/S095026880700845X. PMID 17433131.

- ↑ Rotem, Tamar (August 11, 2007). "Current measles outbreak hit ultra-Orthodox the hardest". Haaretz. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/921836.html. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ Batty, David (Friday 9 January 2009 15.38 GMT). "Record number of measles cases sparks fear of epidemic". London: guardian.co.uk. http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2009/jan/09/measles-record-numbers. Retrieved January 15th, 2009.

- ↑ Eurosurveillance - View Article

- ↑ North York: Measles outbreak may bring new strategy, May 2008

- ↑ "Measles outbreak shows a global threat - The Boston Globe". 2006-06-10. http://www.boston.com/yourlife/health/diseases/articles/2006/06/10/measles_outbreak_shows_a_global_threat/. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ↑ Jesse, David (October 4, 2007). "Measles outbreak may have spread". The Ann Arbor News. http://blog.mlive.com/study_hall/2007/10/measles_outbreak_may_have_spre.html. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ "CDC.gov". http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm57e501a1.htm?s_cid=mm57e501a1_e. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ JS Online: Measles outbreak brewing, city health officials say

- ↑ "cdc.gov MeaslesUpdate". http://www.cdc.gov/Features/MeaslesUpdate/. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ Rotstein, Arthur (July 9, 2008). "Response curtailed measles outbreak". Associated Press. http://www.tucsoncitizen.com/daily/local/90471.php. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ Dunham, Will (July 9, 2008). "Measles outbreak hits 127 people in 15 states". Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/newsOne/idUSN0943743120080709. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

External links

- WHO.int - 'Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR): Measles', World Health Organization (WHO)

- Measles FAQ from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States

- Case of an adult male with measles (facial photo)

- Clinical pictures of measles

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||