Mi'kmaq

|

| Grand Council Flag of the Mi'kmaq Nation [1] |

| Total population |

|---|

| 40,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Canada (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec), United States (Maine) |

| Languages |

| Religion |

|

Christianity, Míkmaq Traditionalism and Spirituality, others |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

other Algonquian peoples |

The Míkmaq (pronounced [miːɡmax]) are a First Nations (Native American) people, indigenous to northeastern New England, Canada's Atlantic Provinces, and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec. The nation has a population of about 40,000 of whom nearly 11,000 speak the Algonquian language Lnuísimk, more commonly known as "Micmac".[2][3][4] Once written in Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing, Lnuísimk is now written using most letters of the standard Latin alphabet.

Their name has traditionally been spelled Micmac in English (pronounced /ˈmɪkmæk/), but the natives have used different spellings: Mi’kmaq (singular Mi’kmaw) by the Míkmaq of Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia, Miigmaq (Miigmao) by the Míkmaq of New Brunswick, Mi’gmaq by the Listuguj Council in Quebec, or Mìgmaq (Mìgmaw) in some native literature.[5] Until the 1980s, "Micmac" remained the most common spelling in English. Although still used, for example, in Ethnologue, this spelling has fallen out of favour in recent years. Most scholarly publications use the preferred native spelling of Mi'kmaq.[6] The Míkmaq prefer to use one of the three current Míkmaq orthographies when writing in English or French.[7] They consider the English spelling to be "colonially tainted."[5]

Contents |

Etymology

Lnu (the adjectival and singular noun, previously spelled "L'nu"; the plural is Lnúk, Lnu’k, Lnu’g, or Lnùg) is the self-recognized term for the Míkmaq of New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Maine, meaning "human being" or "the people".[8]

Various explanations exist for the origin of the term Míkmaq. The Mi'kmaw Resource Guide states that "Míkmaq" means "the family":

The definite article "the" suggests that "Mi'kmaq" is the undeclined form indicated by the initial letter "m". When declined in the singular it reduces to the following forms: nikmaq - my family; kikmaq - your family; wikma - his/her family. The variant form Mi'kmaw plays two grammatical roles: 1) It is the singular of Mi'kmaq and 2) it is an adjective in circumstances where it precedes a noun (e.g. mi'kmaw people, mi'kmaw treaties, mi'kmaw person, etc.)[9]

However, there are other hypotheses:

The name "Micmac" was first recorded in a memoir by de La Chesnaye in 1676. Professor Ganong in a footnote to the word megamingo (earth), as used by Marc Lescarbot, remarked "that it is altogether probable that in this word lies the origin of the name Micmac." As suggested in this paper on the customs and beliefs of the Micmacs, it would seem that megumaagee the name used by the Micmacs, or the Megumawaach, as they called themselves, for their land, is from the words megwaak, "red", and magumegek, "on the earth", or as Rand recorded, "red on the earth," megakumegek, "red ground," "red earth." The Micmacs, then, must have thought of themselves as the Red Earth People, or the People of the Red Earth. Others seeking a meaning for the word Micmac have suggested that it is from nigumaach, my brother, my friend, a word that was also used as a term of endearment by a husband for his wife... Still another explanation for the word Micmac suggested by Stansbury Hagar in "Micmac Magic and Medicine" is that the word megumawaach is from megumoowesoo, the name of the Micmacs' legendary master magicians, from whom the earliest Micmac wizards are said to have received their power.[10]

Members of the Mi'kmaq First Nation historically referred to themselves as Lnu, but used the term níkmaq (my kin) as a greeting. The French initially referred to the Míkmaq as Souriquois"[11] and later as Gaspesiens or (through English) "Mickmakis". The British originally referred to them as Tarrantines.[12]

History

The Mi'kmaw territory was divided into seven traditional "districts". Each district had its own independent government and boundaries. The independent governments had a district chief and a council. The council members were band chiefs, elders, and other worthy community leaders. The district council was charged with performing all the duties of any independent and free government by enacting laws, justice, apportioned fishing and hunting grounds, made war, and sued for peace, etc.

The Seven Mi'kmaq Districts are Kespukwitk, Sikepnékatik, Eskíkewaq, Unamákik, Piktuk aqq Epekwitk, Sikniktewaq, and Kespékewaq.

In addition to the district councils, there was also a Grand Council or Santé Mawiómi. The Grand Council composed of "Keptinaq", or Captains in English, who were the district chiefs. Also Elders, the Putús (Wampum belt reader, historian, and dealt with the treaties with the non-natives and other Native tribes), the women council, and the Grand Chief. The Grand Chief was a title given to one of the district chiefs, which was usually from the Mi'kmaq district of Unamáki or Cape Breton Island. This title was hereditary and usually went to the Grand Chief's eldest son. The Grand Council met on a little island on the Bras d'Or lake in Cape Breton called "Mniku", on a reserve today call Chapel Island or Potlotek. To this day, the Grand Council still meet at the Mniku to discuss current issues within the Mi'kmaq Nation.

The Mi'kmaq were members of the Wapnáki (Wabanaki Confederacy), an alliance with four other Algonquian-language nations: the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet. The allied tribes ranged from present-day New England in the United States to the Maritime Provinces of Canada. At the time of contact with the French (late 16th century), they were expanding from their maritime base westward along the Gaspé Peninsula /St. Lawrence River at the expense of Iroquoian Mohawk tribes, hence the Míkmaq name for this peninsula, Kespek ("last-acquired"). On 24 June 1610, Grand Chief Membertou converted to Catholicism and was baptised. He concluded an alliance with the French Jesuits which affirmed the right of Mi'kmaq to choose Catholicism, Mi'kmaw tradition, or both.

The Mi'kmaq, as allies with the French, were amenable to limited French settlement in their midst. After France lost political control of Acadia in 1710, the Mí'kmaq engaged in intermittent warfare with the British. For example, along with Acadians, the Mi'kmaq used military force to resist the founding of British (protestant) settlements in Dartmouth and Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. During the French and Indian War, the Mi'kmaq assisted the Acadians in resisting the British during the Expulsion of the Acadians. The military resistance ended with the French defeat at the Siege of Louisbourg (1758) in Cape Breton. After the war, the Mi'kmaq soon found themselves overwhelmed by the British, who seized much of their land without payment.

Between 1725 and 1779, the Mí'kmaq signed a series of peace and friendship treaties with Great Britain, but none of these were land cession treaties. The nation historically consisted of seven districts, which was later expanded to eight with the ceremonial addition of Great Britain at the time of the 1749 treaty.

Later the Mí'kmaq also settled Newfoundland as the unrelated Beothuk tribe became extinct. Mí'kmaq delegates concluded the first international treaty with the United States soon after its declaration of independence, the Treaty of Watertown, in July 1776. These delegates did not officially represent the Mi'kmaq government, although many individual Mi'kmaq did privately join the Continental army as a result.

On August 31, 2010, the governments of Canada and Nova Scotia signed an historic agreement with the Mi'kmaq Nation, etablishing a process whereby they must consult with the Mi'kmaq Grand Council before engaging in any activities or projects that affect the Mi'kmaq in Nova Scotia — which covers most, if not all, actions these governments might take within that jurisdiction. This is the first such collaborative agreement in Canadian history including all the First Nations within an entire province.[13]

Míkmaq First Nation subdivisions

Míkmaw names in the table are spelled according to several orthographies. The Míkmaw orthographies in use are Míkmaw pictographs, the orthography of Silas Tertius Rand, the Pacifique orthography, and the most recent Smith-Francis orthography, which has been adopted throughout Nova Scotia and in most Míkmaw communities.

| Community | Province/State | Town/Reserve | Est. Pop. | Míkmaq name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abegweit First Nation | Scotchfort, Rocky Point, Morell | 396 | Epekwitk | |

| Acadia | Yarmouth | 996 | Malikiaq | |

| Annapolis Valley | Cambridge Station | 219 | Kampalijek | |

| Aroostook Band of Micmac | Presque Isle | 920 | Ulustuk | |

| Bear River First Nation | Bear River | 272 | Lsetkuk | |

| Buctouche First Nation | Buctouche | 80 | Puktusk | |

| Burnt Church First Nation | Burnt Church 14 | 1,488 | Esk |

|

| Chapel Island First Nation | Chapel Island | 576 | Potlotek | |

| Eel Ground First Nation | Eel Ground | 844 | Natuaqanek | |

| Eel River Bar First Nation | Eel River Bar | 589 | Ugpi'gangij | |

| Elsipogtog First Nation | Big Cove | 3000+ | Lsipuktuk | |

| Eskasoni First Nation | Eskasoni | 3,800+ | Wékistoqnik | |

| Fort Folly First Nation | Dorchester | 105 | Amlamkuk Kwesawék | |

| Micmacs of Gesgapegiag | Maria | 1,174 | Keskapekiaq | |

| Nation Micmac de Gespeg | Fontenelle | 490 | Kespék | |

| Glooscap First Nation | Hantsport | 360 | Pesikitk | |

| Indian Island First Nation | Indian Island | 145 | Lnui Menikuk | |

| Lennox Island First Nation | Lennox Island | 700 | Lnui Mnikuk | |

| Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation | Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation | 3,166 | Listikujk | |

| Membertou First Nation | Sydney | 1,051 | Maupeltuk | |

| Metepenagiag Mi'kmaq Nation | Red Bank | 527 | Metepnákiaq | |

| Miawpukek First Nation | Conne River | 2,366 | Miawpukwek | |

| Millbrook First Nation | Truro | 1400 | Wékopekwitk | |

| Pabineau First Nation | Bathurst | 214 | Kékwapskuk | |

| Paq’tnkek First Nation | Afton | 500 | Paqtnkek | |

| Pictou Landing First Nation | Trenton | 547 | Puksaqtéknékatik | |

| Indian Brook First Nation | Indian Brook (Shubenacadie) | 2,120 | Sipekníkatik | |

| Wagmatcook First Nation | Wagmatcook | 623 | Waqm |

|

| Waycobah First Nation | Whycocomagh | 900 | Wékoqmáq |

Demographics

| Year | Population | Verification |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 4,500 | Estimation |

| 1600 | 3,000 | Estimation |

| 1700 | 2,000 | Estimation |

| 1750 | 3,000 | Estimation |

| 1800 | 3,100 | Estimation |

| 1900 | 4,000 | Census |

| 1940 | 5,000 | Census |

| 1960 | 6,000 | Census |

| 1972 | 10,000 | Census |

| 1998 | 15,000 | SIL |

| 2006 | 20,000 | Census |

The pre-contact population is estimated at 50,000-100,000. In 1616, Father Biard believed the Míkmaq population to be in excess of 3,000, but he remarked that, because of European diseases, there had been large population losses during the 16th century. Smallpox, wars and alcoholism led to a further decline of the native population, which was probably at its lowest in the middle of the 17th century. Then the numbers grew slightly again, apparently stable during the 19th century. During the 20th century, the population was on the rise again. The average growth from 1965 to 1970 was about 2.5%.

Celebrations

In the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador, October is celebrated as Míkmaq History Month and the entire Nation celebrates Treaty Day annually on October 1. This was first signified in the year, 1752, with the Peace and Friendship Treaty (also called the Treaty of 1752) signed by Chief Cope of Shubenacadie, representing all of the Míkmaq people, and the king's representative. It was stated that if the natives would be given gifts annually,"as long as they continued in Peace."[14]

Notable Míkmaq

- Noel Jeddore, Saqmaw forced into exile (1865–1944)

- Kevin Cloud

- Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, activist (1946–1976)

- Henri Membertou, kji-saqmaw/puowin (c.1525-1611)

- Rita Joe, poet

- Donald Marshall Jr.

- Chad Denny, ice hockey player for the Lewiston MAINEiacs and Atlanta Thrashers draftee

- Ashton Bernard, ice hockey player for the Cape Breton Screaming Eagles and New Jersey Devils draftee

- Lionel Little Eagle Pinn, Kitpoviosee, Writer

- Sandy McCarthy, played for the Calgary Flames ice hockey team

- Everett Sanipass, played for the Quebec Nordiques ice hockey team

- Ciara Loyer, played for the kickboxing team in British Columbia

- Lee (Harvey) Cremo, musician (1938–1999)

- Chief Noel Doucette (1938–1996)

- Noel Knockwood, Mi'kmaq Grand Council member and spiritual leader of the Mi'kmaq People

- L'kimu, legendary Mi'kmaq Chief

Pre-Contact Culture

Housing

Mi'kmaq people lived in structures called wigwams. Saplings, which were usually spruce, were cut down and bent over a circle drawn on the ground. These saplings were lashed together at the top, and then covered with birch bark. The Mi'kmaq had two different sizes of wigwams, the smaller size, could hold 10-15 people, and the larger size, could hold 15-20 people. Wigwams could be either conical or domed in shape.

Food/Hunting

The Mi'kmaq were semi-nomadic. During the summer they spent most of their time on the shores harvesting seafood; during the winter they would move inland to the woods to hunt. The most important animal hunted by the Mi'kmaq was the moose which provided food, clothing, cordage, and other things. Other animals hunted/trapped included deer, caribou, bear, rabbit, beaver, and others. The weapon used most for hunting was the bow and arrow. The Mi'kmaq made their bows from maple.

Hunting a moose

The moose was the most important animal to the Mi'kmaq, it was their main meat, clothing, and cordage source, all crucial things to the well-being of the community. The Mi'kmaq usually hunted moose in groups of 3-5 men. Before the moose hunt, the Mi'kmaq would starve their dogs for 2 days, this way they would be fierce in helping to finish off the moose. To kill the moose, they would injure it first, by using a bow and arrow, or other weapons, and after it was down, they would move in on it and finish it off with spears, and their attacking dogs. The guts would then be fed to the dogs. During this whole process, the men would try to direct the moose in the direction of the camp, this way the women would not have to go as far to drag the moose back. A boy became a man in the eyes of the community after he had killed his first moose. It was only then he had earned the right to marry.

Other

One spiritual capital of the Míkmaq nation is Mniku, the gathering place of the Míkmaq Grand Council or Santé Mawiómi, Chapel Island in the Bras d'Or Lakes of Cape Breton Island. The island is also the site of the St. Anne Mission, an important pilgrimage site for the Míkmaq. The island has been declared a historic site.[15]

See also

- Treaty of Watertown

- Elsipogtog First Nation

- Canada Post French Settlement Series

- Alquimou

Notes

- ↑ Flags of the World

- ↑ Ethnologue

- ↑ Statistics Canada 2006

- ↑ Indigenous Languages Spoken in the United States

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Emmanuel Metallic et al., 2005, The Metallic Mìgmaq-English Reference Dictionary

- ↑ Mi'kmaq Landscapes by Anne-Christine Hornborg (2008), p. 3

- ↑ "it is now the preferred choice of our People." Daniel Paul, We Were Not the Savages, 2000, p. 10

- ↑ The Nova Scotia Museum's Míkmaq Portraits database

- ↑ Mi'kmaw Resource Guide, Eastern Woodlands Publishing (1997)

- ↑ cited in Paul to Marion Robertson, Red Earth: Tales of the Micmac, with an introduction to their customs and beliefs (1965) p. 5.

- ↑ Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France

- ↑ Lydia Affleck and Simon White. "Our Language". Native Traditions. http://www.peicaps.org/betweengen/circle/language.html. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- ↑ Mi'kmaq of Nova Scotia, Province of Nova Scotia and Canada Sign Landmark Agreement

- ↑ Treaty of 1752|http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/al/hts/tgu/pubs/pft1752/pft1752-eng.asp

- ↑ CBCnews. Cape Breton Míkmaq site recognized

References

- Bock, Philip K. 1978. "Micmac." pp. 109–122. In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Bruce G. Trigger, editor. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Davis, Stephen A. 1998. Míkmaq: Peoples of the Maritimes, Nimbus Publishing.

- Paul, Daniel N. 2000. We Were Not the Savages: A Míkmaq Perspective on the Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations, Fernwood Pub.

- Prins, Harald E. L. 1996. The Míkmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival (Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology), Wadsworth.

- Rita Joe, Lesley Choyce. 2005. The Míkmaq Anthology, Nimbus Publishing (CN), 2005, ISBN 1-895900-04-2

- Robinson, Angela 2005. Tán Teli-Ktlams

itasit (Ways of Believing): Míkmaw Religion in Eskasoni, Nova Scotia. Pearson Education, ISBN 0-13-177067-5. - Whitehead, Ruth Holmes. 2004. The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts from Míkmaq History 1500-1950, Nimbus Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-921054-83-1

- Wicken, William C. 2002. Míkmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior, University of Toronto Press.

http://www.cmmns.com/KekinamuekPdfs/Ch2screen.pdf

Documentary film

- Our Lives in Our Hands (Míkmaq basketmakers and potato diggers in northern Maine, 1986) [1]

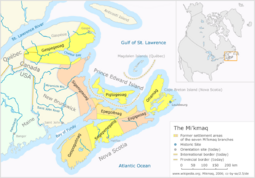

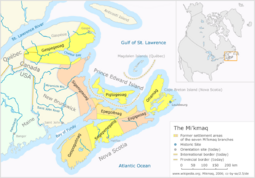

Maps

Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

Mi'kmaq |

Maliseet, Passamaquoddy |

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket) |

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook |

External links

- First Nations Profiles

- Micmac History

- Míkmaq Portraits Collection

- Míkmaq Dictionary Online

- The Micmac of Megumaagee

- Míkmaq Learning Resource

"Micmacs". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Micmacs". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.- glooscapheritagecentre.com

- Unama'ki Institute of Natural Resources