Miracle

A miracle is an unexpected event attributed to divine intervention. Sometimes an event is also attributed (in part) to a miracle worker, saint, or religious leader. A miracle is sometimes thought of as a perceptible interruption of the laws of nature. Others suggest that God may work with the laws of nature to perform what people perceive as miracles.[1] Theologians say that, with divine providence, God regularly works through created nature yet is free to work without, above, or against it as well.[2]

A miracle is often considered a fortuitous event: compare with an Act of God.

In casual usage, "miracle" may also refer to any statistically unlikely but beneficial event, (such as surviving a natural disaster), or simply a "wonderful" occurrence, regardless of likelihood, such as a birth. Other miracles might be: survival of a terminal illness, escaping a life threatening situation or 'beating the odds.' Some coincidences are perceived to be miracles.[3]

Supernatural acts

In one view, a miracle is a phenomenon not fully explainable by known "laws" of nature, or an act by some supernatural entity or unknown, outside force. Some scientist-theologians such as John Polkinghorne suggest that miracles are not violations of the laws of nature but "exploration of a new regime of physical experience".[4]

The logic behind an event being deemed a miracle varies significantly. Often a religious text, such as the Bible or Quran, states that a miracle occurred, and believers accept this as a fact. However, C.S. Lewis noted that one cannot believe a miracle occurred if one had already drawn a conclusion in one's mind that miracles are not possible at all. He cites the example of a woman he knew who had seen a ghost, who had discounted her experience; claiming it to be some sort of hallucination (because she did not believe in ghosts).

Many conservative religious believers hold that in the absence of a plausible, parsimonious scientific theory, the best explanation for these events is that they were performed by a supernatural being, and cite this as evidence for the existence of a god or gods. However, atheist Richard Dawkins criticises this kind of thinking as a subversion of Occam's Razor.[5] Some adherents of monotheistic religions assert that miracles, if established, are evidence for the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent God.

Finally, miracles would contradict the hypothesis of the Non Overlapping Magisteria proposed by Stephen Jay Gould, in that they would both be evidence for supernatural beings in the theological magisterium, and also subject to scientific investigation.

Religious texts

Hebrew Bible

Descriptions of miracles (Hebrew Ness, נס) appear in the Tanakh. Examples include prophets, such as Elijah who performed miracles like the raising of a widow's dead son (1 Kings 17:17–24) and Elisha whose miracles include multiplying the poor widow's jar of oil (2 Kings 4:1-7) and restoring to life the son of the woman of Shunem (2 Kings 4:18-37).

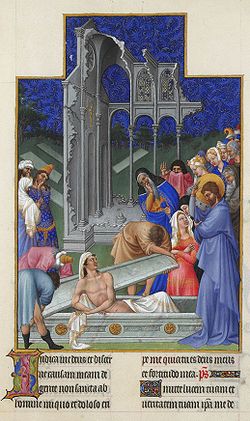

New Testament

The descriptions of most miracles in the Christian New Testament are often the same as the commonplace definition of the word: God intervenes in the laws of nature. In St John's Gospel the miracles are referred to as "signs" and the emphasis is on God demonstrating his underlying normal activity in remarkable ways.[6]

Jesus explains in the New Testament that miracles are performed by faith in God. "If you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mountain, 'move from here to there' and it will move." (Gospel of Matthew 17:20). After Jesus returned to heaven, the book of Acts records the disciples of Jesus praying to God to grant that miracles be done in his name, for the purpose of convincing onlookers that he is alive. (Acts 4:29-31). Other passages mention false prophets who will be able to perform miracles to deceive "if possible, even the elect of Christ" (Matthew 24:24, 2 Thes 2:9, Revelation 13:13).

Qur'an

Miracle in the Qur'an can be defined as a supernatural intervention in the life of human beings.[7] According to this definition, Miracles are present "in a threefold sense: in sacred history, in connection with Muhammad himself and in relation to revelation."[7] The Qur'an does not use the technical Arabic word for miracle (Muʿd̲j̲iza) literally meaning "that by means of which [the Prophet] confounds, overwhelms, his opponents". It rather uses the term 'Ayah' (literally meaning sign).[8] The term Ayah is used in the Qur'an in the above mentioned threefold sense: it refers to the "verses" of the Qur'an (believed to be the divine speech in human language; presented by Muhammad as his chief Miracle); as well as to miracles of it and the signs (particularly those of creation).[7][8]

To defend the possibility of miracles and God's omnipotence against the encroachment of the independent secondary causes, some medieval Muslim theologians such as Al-Ghazali rejected the idea of cause and effect in essence, but accepted it as something that facilitates humankind's investigation and comprehension of natural processes. They argued that the nature was composed of uniform atoms that were "re-created" at every instant by God. Thus if the soil was to fall, God would have to create and re-create the accident of heaviness for as long as the soil was to fall. For Muslim theologians, the laws of nature were only the customary sequence of apparent causes: customs of God.[9]

Events planned by God

In rabbinic Judaism, many rabbis mentioned in the Talmud held that the laws of nature were inviolable. The idea of miracles that contravened the laws of nature were hard to accept; however, at the same time they affirmed the truth of the accounts in the Tanakh. Therefore some explained that miracles were in fact natural events that had been set up by God at the beginning of time.

In this view, when the walls of Jericho fell, it was not because God directly brought them down. Rather, God planned that there would be an earthquake (or some such other natural disaster) at that place and time, so that the city would fall to the Israelites. Instances where rabbinic writings say that God made miracles a part of creation include Midrash Genesis Rabbah 5:45; Midrash Exodus Rabbah 21:6; and Ethics of the Fathers/Pirkei Avot 5:6.

Philosophers' explanations

Fundamentally, no philosopher sticking to the scientific world view could explain the existence or not of miracles, since miracles are incompatible with it by definition. What philosophers discuss is the fact that they could be taken or not as a justification to the existence of supernatural forms of expression different from those given to reason and experience, or in minor intellectual approaches, to what is considered to be fair and unfair from a human God's perspective to be given to the common human claims for palliation of suffering.

Aristotelian and Neo-Aristotelian

Aristotle rejected the idea that God could or would intervene in the order of the natural world. Jewish neo-Aristotelian philosophers, who are still influential today, include Maimonides, Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon, and Gersonides. Directly or indirectly, their views are still prevalent in much of the religious Jewish community.

Baruch Spinoza

In his Theologico-Political Treatise Spinoza claims that miracles are merely lawlike events whose causes we are ignorant of. We should not treat them as having no cause or of having a cause immediately available. Rather the miracle is for combating the ignorance it entails, like a political project. See Epistemic theory of miracles.

David Hume

According to the philosopher David Hume, a miracle is "a transgression of a law of nature by a particular volition of the Deity, or by the interposition of some invisible agent.".[10] The crux of his argument is this: "No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact which it endeavours to establish."

Søren Kierkegaard

The philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, following Hume and Johann Georg Hamann, a Humean scholar, agrees with Hume's definition of a miracle as a transgression of a law of nature,[11] but Kierkegaard, writing as his pseudonym Johannes Climacus, regulates any historical reports to be less than certain, including historical reports of such miracle transgressions, as all historical knowledge is always doubtful and open to approximation.[12]

James Keller

James Keller, along with many other philosophers, states that "The claim that God has worked a miracle implies that God has singled out certain persons for some benefit which many others do not receive implies that God is unfair.”[13] An example would be "If God intervenes to save your life in a car crash, then what was he doing in Auschwitz?". Thus an all-powerful, all-knowing and just God, predicated in Christianity, would not perform miracles.

Nonliteral interpretations of the biblical story

Biblical literalism is not rigidly believed by all scholars: Non-literal interpretations of some scripture are held by both classical and modern thinkers. This may include the use of figure of speech, allegory, and exegesis.

In Numbers 22 is the story of Balaam and the talking donkey. Many hold that for miracles such as this, one must either assert the literal truth of this biblical story, or one must then reject the story as false. However, some Jewish commentators (e.g. Saadiah Gaon and Maimonides) hold that stories such as these were never meant to be taken literally in the first place. Rather, these stories should be understood as accounts of a prophetic experience, which are dreams or visions. (Of course, such dreams and visions could themselves be considered miracles.)

Joseph H. Hertz, a 20th century Jewish biblical commentator, writes that these verses "depict the continuance on the subconscious plane of the mental and moral conflict in Balaam's soul; and the dream apparition and the speaking donkey is but a further warning to Balaam against being misled through avarice to violate God's command."

Products of creative art and social acceptance

In this view, miracles do not really occur. Rather, they are the product of creative story tellers. They use them to embellish a hero or incident with a theological flavor. Using miracles in a story allows characters and situations to become bigger than life, and to stir the emotions of the listener more than the mundane and ordinary.

Misunderstood commonplace events

Littlewood's law states that individuals can expect miracles to happen to them, at the rate of about one per month. By its definition, seemingly miraculous events are actually commonplace. In other words, miracles do not exist, but are rather examples of low probability events that are bound to happen by chance from time to time.

Religious groups

Claims of miracles in Christianity

C.S. Lewis, Norman Geisler, William Lane Craig, and other Christians have argued that miracles are reasonable and plausible. For example, C.S. Lewis says that a miracle is something that comes totally out of the blue. If for thousands of years a woman can become pregnant only by sexual intercourse with a man, then if she were to become pregnant without a man, it would be a miracle.[14][15][16]

There have been numerous claims of miracles in Christianity. This includes the Roman Catholic Church, Christian Science, Protestant, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Evangelical, Pentecostal, Charismatic and others. The types of miracles that are claimed to occur by these denominations are faith healings and casting out demons.

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church recognizes miracles as being works of God, either directly or through the prayers and intercession of a specific Saint or Saints. There is usually a specific purpose connected to a miracle, e.g. the conversion of a person or persons to the Catholic faith or the construction of a church desired by God. The Church tries to be very cautious to approve the validity of putative miracles. It maintains particularly stringent requirements in validating the miracle's authenticity.[17] The process is overseen by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.[18]

The Catholic Church claims to have confirmed the validity of a number of miracles, some of them occurring in modern times and having withstood the test of modern scientific scrutiny. Among the more notable miracles approved by the Church are several Eucharistic miracles wherein the Sacred Host is transformed visibly into Christ's living Flesh and Blood, bleeds, hovers in the air, radiates light, and/or displays the image of Christ. The first example of the Host being visibly changed into human flesh and blood occurred at Lanciano, Italy around 700 A.D. Unlike some miracles of a more transient nature, the Flesh and Blood remain in Lanciano to this day, having been scientifically examined as recently as 1971.

According to 17th-century documents, a young Spanish man's leg was miraculously restored to him in 1640 after having been amputated two and a half years earlier[19] (see miracle of Calanda).

Another miracle approved by the Church is the Miracle of the Sun, which occurred near Fátima, Portugal on October 13, 1917. Anywhere between 70,000 and 100,000 people, who were gathered at a cove near Fátima, witnessed the sun dim, change colors, spin, dance about in the sky, and appear to plummet to earth, radiating great heat in the process. After the ten-minute event, the ground and the people's clothing, which had been drenched by a previous rainstorm, were both dry.

In addition to these, the Catholic Church attributes miraculous causes to many otherwise inexplicable phenomena on a case-by-case basis. Only after all other possible explanations have proven inadequate may the Church assume Divine intervention and declare the miracle worthy of veneration by the faithful. The Church does not, however, enjoin belief in any extra-Scriptural miracle as an article of faith or as necessary for salvation.

Hinduism

The Hindu milk miracle was a phenomenon considered by many Hindus as a miracle that occurred on September 21, 1995.

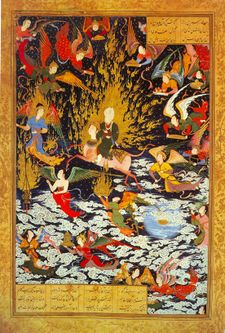

Islam

Sufi biographical literature records claims of miraculous accounts of men and women. The miraculous prowess of the Sufi holy men includes firasa(clairvoyance), the ability to disappear from sight, to become completely invisible and practice buruz(exteriorization). The holy men reportedly tame wild beasts and traverse short distances in a very short time span. They could also produce food and rain in seasons of drought, heal the sick and help barren women become pregnant.[20][21]

Criticism

Thomas Paine, one of the Founding Fathers of the American Revolution, wrote “All the tales of miracles, with which the Old and New Testament are filled, are fit only for impostors to preach and fools to believe”.[22]

Thomas Jefferson, principle author of the Declaration of Independence of the United States, edited a version of the Bible in which he removed sections of the New Testament containing supernatural aspects as well as perceived misinterpretations he believed had been added by the Four Evangelists.[23] [24] Jefferson wrote, "The establishment of the innocent and genuine character of this benevolent moralist, and the rescuing it from the imputation of imposture, which has resulted from artificial systems, [footnote: e.g. The immaculate conception of Jesus, his deification, the creation of the world by him, his miraculous powers, his resurrection and visible ascension, his corporeal presence in the Eucharist, the Trinity; original sin, atonement, regeneration, election, orders of Hierarchy, etc. —T.J.] invented by ultra-Christian sects, unauthorized by a single word ever uttered by him, is a most desirable object, and one to which Priestley has successfully devoted his labors and learning."[25]

Robert Ingersoll wrote, "Not 20 people were convinced by the reported miracles of Christ, and yet people of the nineteenth century were coolly asked to be convinced on hearsay by miracles which those who are supposed to have seen them refused to credit."[26]

Writer Christopher Hitchens, when asked for his favorite Bible story replied “Casting the first stone” is a lovely story, even though we’ve found out how much it wasn’t in the Bible to begin with. And the first of the miracles. Jesus changes water into wine. You can’t object to that."[27]

John Adams, second President of the United States, wrote, "The question before the human race is, whether the God of nature shall govern the world by his own laws, or whether priests and kings shall rule it by fictitious miracles?"[28]

Elbert Hubbard, American writer, publisher, artist, and philosopher, wrote "A miracle is an event described by those to whom it was told by people who did not see it."[29]

American Revolutionary War patriot and hero Ethan Allen wrote "In those parts of the world where learning and science have prevailed, miracles have ceased; but in those parts of it as are barbarous and ignorant, miracles are still in vogue."[30]

See also

- Aikido

- Akhtar Raza

- Apollonius of Tyana

- Audrey Marie Santo

- Buddha

- Cessationism

- A Course in Miracles

- Divine Providence

- Escrava Anastacia

- Intercession of saints

- Jacob Cochran

- The Lourdes effect

- Međugorje

- Magic and religion

- Miracles attributed to Jesus

- Magnets

- Mansur Al-Hallaj

- Miracles at Lourdes

- Occasionalism

- Sabbas the Sanctified

- Sai Baba of Shirdi

- Sathya Sai Baba

- Sarkar Waris Pak

- Signs and wonders

- Spontaneous remission ("medical miracles")

- Snake handling

- Superstition

- Swami Premananda

- Anomaly

- Paranormal

- Vespasian

Notes and references

- ↑ Sproule, R C (1992). Essential Truths of the Christian Faith. Tyndale. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-8423-2001-6.

- ↑ McLaughlin, R (May 2002). "Do Miracles Happen Today?". IIIM Online. Reformed Perspectives Magazine. http://www.thirdmill.org/newfiles/ra_mclaughlin/TH.Mclaughlin.miracles.html. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Halbersam, Yitta (1997). Small Miracles. Adams Media Corp. ISBN 1-55850-646-2.

- ↑ John Polkinghorne Faith, Science and Understanding p.59

- ↑ The God Delusion

- ↑ see e.g. Polkinghorne op cit. and a commentary on the Gospel of John, such as William Temple's Readings in St John's Gospel (see e.g. p. 33) or Tom Wright's John for Everyone

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Denis Gril, Miracles, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 A.J. Wensinck, Muʿd̲j̲iza, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ Robert G. Mourison, The Portrayal of Nature in a Medieval Qur’an Commentary, Studia Islamica, 2002

- ↑ Miracles on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Hume and Kierkegaard by Richard Popkin

- ↑ Kierkegaard on Miracles

- ↑ Keller, James. “A Moral Argument against Miracles,” Faith and Philosophy. vol. 12, no 1. Jan 1995. 54-78

- ↑ "Are Miracles Logically Impossible?". Come Reason Ministries, Convincing Christianity. http://www.comereason.org/phil_qstn/phi060.asp. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "“Miracles are not possible,” some claim. Is this true?". ChristianAnswers.net. http://www.christiananswers.net/q-eden/edn-t011.html. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ↑ Paul K. Hoffman. "A Jurisprudential Analysis Of Hume’s “in Principal” Argument Against Miracles" (PDF). Christian Apologetics Journal, Volume 2, No. 1, Spring, 1999; Copyright ©1999 by Southern Evangelical Seminary. http://www.ses.edu/journal/articles/2.1Hoffman.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ↑ Pathfinder.com

- ↑ 30giorni.it (Italian)

- ↑ Messori, Vittorio (2000): Il miracolo. Indagine sul più sconvolgente prodigio mariano. - Rizzoli: Bur.

- ↑ The heirs of the prophet: charisma and religious authority in Shi'ite Islam By Liyakatali Takim

- ↑ [http://www.sufismjournal.org/history/history.html SAINTS AND MIRACLES]

- ↑ The Writings of Thomas Paine, Volume 4, page 289, Putnam & Sons, 1896

- ↑ Jeremy Kosselak (November 1998). The Exaltation of a Reasonable Deity: Thomas Jefferson’s Bible of Christianity. (Communicated by: Dr. Patrick Furlong). Indiana University South Bend - Department of History. IUSB.edu, Retrieved 2007-02-19

- ↑ R.P. Nettelhorst. Notes on the Founding Fathers and the Separation of Church and State. Quartz Hill School of Theology. Theology.edu Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ↑ Letter to William Short (31 October 1819), published in "The Works of Thomas Jefferson in Twelve Volumes", Federal Edition, Paul Leicester Ford, ed., New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1904, Vol. 12, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ New York Times, p. 8, April 24, 1882

- ↑ New York Magazine, April 26, 2007

- ↑ John Adams, letter to Thomas Jefferson, June 20, 1815

- ↑ Elbert Hubbard, The Philistine (1909)

- ↑ Ethan Allen, Reason, the Only Oracle of Man, 1784

General references and books

- Colin Brown. Miracles and the Critical Mind. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1984. (Good survey).

- Colin J. Humphreys, Miracles of Exodus. Harper, San Francisco, 2003.

- Krista Bontrager, "It’s a Miracle! Or, is it?", Reasons.org

- Eisen, Robert (1995). Gersonides on Providence, Covenant, and the Chosen People. State University of New York Press.

- Goodman, Lenn E. (1985). Rambam: Readings in the Philosophy of Moses Maimonides. Gee Bee Tee.

- Kellner, Menachem (1986). Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought. Oxford University Press.

- C. S. Lewis. Miracles: A Preliminary Study. New York, Macmillan Co., 1947.

- C. F. D. Moule (ed.). Miracles: Cambridge Studies in their Philosophy and History. London, A.R. Mowbray 1966, ©1965 (Good survey of Biblical miracles as well).

- Graham Twelftree. Jesus the Miracle Worker: A Historical and Theological Study. IVP, 1999. (Best in its field).

- Woodward, Kenneth L. (2000). The Book of Miracles. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82393-4.

- M. Kamp, MD. Bruno Gröning. The miracles continue to happen. 1998, (Chapters 1-4), Bruno-Groening.org

Further reading

- Houdini, Harry Miracle Mongers and Their Methods: A Complete Expose Prometheus Books; Reprint edition (March 1993) originally published in 1920 ISBN 0-87975-817-1.

- Andrew Dickson White (1896 first edition. A classic work constantly reprinted) A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, See chapter 13, part 2, Growth of Legends of Healing: the life of Saint Francis Xavier as a typical example.

- Rory Roybal Miracles or Magic?. Xulon Press, 2005.

External links

- SMAjournalonline.com, the history of thinking about miracles in the West

- Mukto-mona.com, an Indian Skeptic's explanation of miracles: By Yuktibaadi, compiled by Basava Premanand

- Skepdic.com, skeptic's dictionary on miracles

- Andrew Lang, Psychanalyse-paris.com, "Science and 'Miracles'", The Making of Religion Chapter II, Longmans, Green, and Co., London, New York and Bombay, 1900, pp. 14–38.

- Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.- "Miracle" in the Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science.

- CBN Video: Living a Life of Miracles

- CBN Video: Miracles Outside the Church Walls

- Testimonies on iBethel.tv

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||