Nasreddin

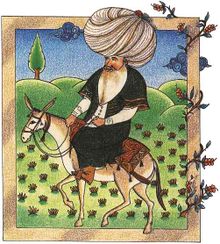

Nasreddin is a fictional legendary satirical Sufi figure who is believed by some to have existed during the Middle Ages (around 13th century), in Akşehir, and later in Konya, under the Seljuq rule. Nasreddin was a populist philosopher and wise man, remembered for his funny stories and anecdotes.[1]

Contents |

Nomenclature, orthography and etymology

Nomenclature

Nasreddin (Turkish "Nasrettin Hoca", Turkmen "Hoja Nasretdin" or "Ependi", Persian ملا نصرالدین, Tajik "Khoja Nasreddin" or "Afandi", Azeri"Molla Nəsrəddin", Kurdish "Mella Nasredîn", Arabic: جحا juḥā, نصرالدين naṣr ad-dīn meaning "Victory of the faith" (i.e. Islam), transl.: Malai Mash-hoor, Albanian "Nastradin Hoxha" or just "Nastradini", Bosnian "Nasrudin Hodža", Chinese 阿凡提, Uzbek "Nasriddin Afandi" or just "Afandi", Kazakh: Қожанасыр "Khozhanasir", Uyghur "Näsirdin Äfänti", Greek Ναστραντίν Χότζας or Νασρεντίν Χότζας, Romanian "Nastratin Hogea" [2][3][4] )[1]

Orthography

Etymology

Detail

Many nations of the Near, Middle East and Central Asia claim the Nasreddin as their own, but if Nasreddin did truly exist, it is most likely that he was Turkish (i.e. Turks,[1][5][6][7] Afghans,[5] Iranians,[1][8] and Uzbeks)[9], and his name is spelled differently in various cultures—and often preceded or followed by titles "Hodja", "Mullah", or "Effendi".

1996–1997 was declared International Nasreddin Year by UNESCO[10].

Origin & legacy

Nasreddin lived in Anatolia, Turkey; he was born in Hortu Village in Sivrihisar, Eskişehir in the 13th century, then settled in Akşehir, and later in Konya, where he died (probably born in 1209 CE and died 1275/6 or 1285/6 CE).[6][9]

As generations went by, new stories were added, others were modified, and the character and his tales spread to other regions. The themes in the tales have become part of the folklore of a number of nations and express the national imaginations of a variety of cultures. Although most of them depict Nasreddin in an early small-village setting, the tales (like Aesop's fables) deal with concepts that have a certain timelessness. They purvey a pithy folk wisdom that triumphs over all trials and tribulations. The oldest manuscript of Nasreddin was found in 1571.

Today, Nasreddin stories are told in a wide variety of regions, and have been translated into many languages. Some regions independently developed a character similar to Nasreddin, and the stories have become part of a larger whole. In many regions, Nasreddin is a major part of the culture, and is quoted or alluded to frequently in daily life. Since there are thousands of different Nasreddin stories, one can be found to fit almost any occasion.[11] Nasreddin often appears as a whimsical character of a large Albanian, Arab, Armenian, Azeri, Bengali, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Greek, Chinese, Russian, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Romanian, Serbian, Turkish and Urdu folk tradition of vignettes, not entirely different from zen koans. He is also very popular in Greece for his wisdom and his judgement; he is also known in Bulgaria, although in a different role, see below. He has been very popular in China for many years, and still appears in variety of movies, cartoons, and novels.

The "International Nasreddin Hodja Festival" is held annually in Akşehir between July 5–10.[12]

Tales

.jpg)

The Nasreddin stories are known throughout the Middle East and have touched cultures around the world. Superficially, most of the Nasreddin stories may be told as jokes or humorous anecdotes. They are told and retold endlessly in the teahouses and caravanserais of Asia and can be heard in homes and on the radio. But it is inherent in a Nasreddin story that it may be understood at many levels. There is the joke, followed by a moral — and usually the little extra which brings the consciousness of the potential mystic a little further on the way to realization.[13]

Examples

Delivering a sermon

- Once Nasreddin was invited to deliver a sermon. When he got on the pulpit, he asked, "Do you know what I am going to say?" The audience replied "no", so he announced, "I have no desire to speak to people who don't even know what I will be talking about!" and left.

- The people felt embarrassed and called him back again the next day. This time, when he asked the same question, the people replied "yes". So Nasreddin said, "Well, since you already know what I am going to say, I won't waste any more of your time!" and left.

- Now the people were really perplexed. They decided to try one more time and once again invited the Mullah to speak the following week. Once again he asked the same question - "Do you know what I am going to say?" Now the people were prepared and so half of them answered "yes" while the other half replied "no". So Nasreddin said "Let the half who know what I am going to say, tell it to the half who don't," and left.

Who do you trust

- A neighbour came to the gate of Mulla Nasreddin's yard. The Mulla went to meet him outside.

- "Would you mind, Mulla," the neighbour asked, "lending me your donkey today? I have some goods to transport to the next town."

- The Mulla didn't feel inclined to lend out the animal to that particular man, however. So, not to seem rude, he answered:

- "I'm sorry, but I've already lent him to somebody else."

- All of a sudden the donkey could be heard braying loudly behind the wall of the yard.

- "But Mulla," the neighbour exclaimed. "I can hear it behind that wall!"

- "Who do you believe," the Mulla replied indignantly. "The donkey or your Mulla?"

Taste the same

- Some children saw Nasreddin coming from the vineyard with two basketfuls of grapes loaded on his donkey. They gathered around him and asked him to give them a taste.

- Nasreddin picked up a bunch of grapes and gave each child a grape.

- "You have so much, but you gave us so little," the children whined.

- "There is no difference whether you have a basketful or a small piece. They all taste the same," Nasreddin answered, and continued on his way.

European and Western folk tales, literary works and pop culture

In some Bulgarian and Macedonian folk tales that originated during the Ottoman period, the name appears as an antagonist to a local wise man, named Sly Peter. In Sicily the same tales involve a man named Giufà.[14] In Sephardi Jewish culture, spread throughout the Ottoman Empire, there is a character that appears in many folk tales named Djohá.[15][16]

While Nasreddin is mostly known as a character from anecdotes, whole novels and stories have later been written and an animated feature film was almost made.[17] In 1943 Soviet film Nasreddin in Bukhara was directed by Yakov Protazanov.

In Russia Nasreddin is known mostly because of the novel "Tale of Hodja Nasreddin" written by Leonid Solovyov (English translations: "The Beggar in the Harem: Impudent Adventures in Old Bukhara," 1956, and "The Tale of Hodja Nasreddin: Disturber of the Peace," 2009 [18]). Composer Shostakovich celebrates Nasreddin, among other figures, in the second movement (Yumor, 'Humor') of his Symphony No. 13. The text, by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, portrays humor as a weapon against dictatorship and tyranny. Shostakovich's music shares many of the 'foolish yet profound' qualities of Nasreddin's sayings listed above.

Uzbek Nasriddin Afandi

For Uzbek people Nasriddin is one of their own. In gatherings, family meetings, parties they tell each other stories about him that are called "latifa" of "afandi".

There are at least two collections of stories related to Nasriddin Afandi.

Books on him:

- "Afandining qirq bir passhasi" - (Forty-one flies of Afandi) - Zohir A'lam, Tashkent

- "Afandining besh xotini" - (Five wives of Afandi)

Even a film was produced by Uzbekistan SSR called "Nasriddin Buxoroda" ("Nasriddin in Bukhara")

Collections

- 600 Mulla Nasreddin Tales, collected by Mohammad Ramazani (Popular Persian Text Series: 1) (in Persian).

- The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin, by Idries Shah, illustrated by Richard Williams

- The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin, by Idries Shah, illustrated by Richard Williams.

- The Pleasantries of the Incredible Mulla Nasrudin, by Idries Shah, illustrated by Richard Williams and Errol Le Cain

- Mullah Nasiruddiner Galpo (Tales of Mullah Nasreddin) collected and retold by Satyajit Ray, in Bengali

- The Wisdom of Mulla Nasruddin, by Shahrukh Husain

Name

Nasreddin's name is also commonly spelled Nasrudeen, Nasruddin, Nasr ud-Din, Nasredin, Naseeruddin, Nasruddin, Nasr Eddin, Nastradhin, Nasreddine, Nastratin, Nusrettin, Nasrettin, Nostradin and Nastradin (lit.: Victory of the Deen).

His name is sometime preceded or followed by a title of wisdom used in the corresponding cultures: "Hoxha", "Khwaje", "Hodja", "Hojja","Hodscha", "Hodža", "Hoca", "Hogea".

In Arabic-speaking countries this character is known as "Juha", "Djoha", "Djuha", "Dschuha", "Giufà", "Chotzas", "Goha" (جحا juḥā), "Mullah", "Mulla", "Mula", "Molla", "Maulana", "Efendi", "Afandi", "Ependi" (أفندي ’afandī), "Hajji". In several cultures his name is just the title.

In the Swahili culture many of his stories are being told under the name of "Abunuwasi", though this confuses Nasreddin with an entirely different man - the poet Abu Nuwas, known for homoerotic verse.

In China, where stories of him are well known, he is known by the various transliterations from his Uyghur name, 阿凡提 (Āfántí) and 阿方提 (Āfāngtí). Shanghai Animation Film Studio produced a 13-episode Nasreddin related Animation called 'The Story of Afanti'/ 阿凡提 (电影) in 1979, which became one of the most influential animations in China's history.

In Central Asia, he is commonly known as "Afandi".

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 The outrageous Wisdom of Nasruddin, Mullah Nasruddin; accessed February 19, 2007.

- ↑ "Afanti de gu shi" (A collection of the Uighur people's folktales as well as information about their customs and life styles) ISBN 957-691-004-8

- ↑ J.C. Yang, Xenophobes Guide to the Chinese, Oval Books, ISBN 1-902825-22-5

- ↑ "The Effendi And The Pregnant Pot - Uygur Tales from China"; New World Press; Beijing, China

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sysindia.com, Mulla Nasreddin Stories, accessed February 20, 2007.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Nasreddin Hoca". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. http://www.kultur.gov.tr/EN/BelgeGoster.aspx?17A16AE30572D3138DF7C92FCA5B4D0584F186FD0FCCD518. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ Silk-road.com, Nasreddin Hoca

- ↑ "First Iranian Mullah who Was a Master in Anecdotes". Persian Journal. http://www.iranian.ws/iran_news/publish/printer_28786.shtml. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Fiorentini, Gianpaolo (2004). "Nasreddin, una biografia possibile". Storie di Nasreddin. Torino: Libreria Editrice Psiche. ISBN 8885142710. http://www.psiche.info/estratti/psiche/StorieDiNasreddin.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ [http://www.rri.ro/art.shtml?lang=1&sec=170&art=27256 "...UNESCO declared 1996-1997 the International Nasreddin Year, and a festival bearing Nastratin’s name is held each year in Akshehir, in July. ..."]

- ↑ Ohebsion, Rodney (2004) A Collection of Wisdom, Immediex Publishing, ISBN 1-932968-19-9.

- ↑ Akşehir's International Nasreddin Hoca Festival and Aviation Festival - Turkish Daily News Jun 27, 2005

- ↑ Idris Shah (1964), The Sufis, London: W. H. Allen ISBN 0-385-07966-4. :D

- ↑ Google Books Search

- ↑ Tripod.com, Djoha - Personaje - Ponte en la Area del Mediterraneo

- ↑ Sefarad.org, European Sephardic Institute

- ↑ Dobbs, Mike (1996), "An Arabian Knight-mare", Animato! (35)

- ↑ Solovyov, Leonid (2009). The Tale of Hodja Nasreddin: Disturber of the Peace. Toronto, Canada: Translit Publishing. ISBN 9780981269504. http://translit.ca/books.html#disturber.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||