Noh

Noh (能 Nō), or Nogaku (能楽 Nōgaku)[1] is a major form of classical Japanese musical drama that has been performed since the 14th century. Many characters are masked, with men playing male and female roles. The repertoire is normally limited to a specific set of historical plays. A Noh performance often lasts all day and consists of five Noh plays interspersed with shorter, humorous kyōgen pieces.

While the field of Noh performance is extremely codified with an emphasis on tradition rather than innovation, some performers do compose new plays or revive historical ones that are not a part of the standard repertoire. Works blending Noh with other theatrical traditions have also been produced.

Contents |

History

Together with the closely related kyōgen farce, it evolved from various popular, folk and aristocratic art forms, including Dengaku, Shirabyoshi, and Gagaku.

Kan'ami and his son Zeami brought Noh to its present-day form during the Muromachi period under the patronage of the powerful Ashikaga clan. It would later influence other dramatic forms such as Kabuki and Butoh. During the Meiji era, although its governmental patronage was lost, Noh and Kyōgen received official recognition as two of the three national forms of drama.

By tradition, Noh actors and musicians never rehearse for performances together. Instead, each actor, musician, and choral chanter practices his or her fundamental movements, songs, and dances independently or under the tutelage of a senior member of the school. Thus, the tempo of a given performance is not set by any single performer but established by the interactions of all the performers together. In this way, Noh exemplifies the traditional Japanese aesthetic of transience, called by Sen no Rikyu "ichi-go ichi-e".

Roles

There are four major categories of Noh performers: shite, waki, kyōgen, and hayashi.[2]

- Shite (仕手, シテ), literally "doers" are the most common roles in Noh.

- Shite (primary actor). In plays where the shite appears first as a human and then as a ghost, the first role is known as the maeshite and the later as the nochishite.

- Shitezure (仕手連れ, シテヅレ). The shite's companion. Sometimes shitezure is abbreviated to tsure (連れ, ツレ), although this term refers to both the shitezure and the wakizure.

- Kōken (後見) are stage hands, usually one to three people.

- Jiutai (地謡) is the chorus, usually comprising six to eight people.

- Waki (脇, ワキ) performs the role that is the counterpart or foil of the shite.

- Wakizure (脇連れ, ワキヅレ) or Waki-tsure is the companion of the waki.

- Kyōgen (狂言) perform the aikyōgen (相狂言) interludes during plays. Kyōgen actors also perform in separate plays between individual noh plays.

- Hayashi (囃子) or hayashi-kata (囃子方) are the instrumentalists who play the four instruments used in Noh theater: the transverse flute (笛 fue), hip drum (大鼓 okawa or ōtsuzumi), the shoulder-drum (小鼓 kotsuzumi), and the stick-drum (太鼓 taiko ). The flute used for noh is specifically called nōkan or nohkan (能管).

A typical Noh play will involve four or five categories of actors and usually takes 30-120 minutes. Noh actors were almost exclusively male.

Plays

There are approximately 250 plays in the current repertoire, which can be divided according to a variety of schemes. The most common is according to content, but there are several other methods of organization.[3]

Categories

- Kami mono (神物) or waki nō (脇能) typically feature the shite in the role of a human in the first act and a deity in the second and tell the mythic story of a shrine or praise a particular spirit.

- Shura mono (修羅物) or ashura nō (阿修羅能, warrior plays) have the shite often appearing as a ghost in the first act and a warrior in full battle regalia in the second, re-enacting the scene of his death.

- Katsura mono (鬘物, wig plays) or onna mono (女物, woman plays) depict the shite in a female role and feature some of the most refined songs and dances in all of Noh.

- There are about 94 "miscellaneous" plays, including kyōran mono (狂乱物) or madness plays, onryō mono (怨霊物) or vengeful ghost plays, and genzai mono (現在物), plays which depict the present time, and which do not fit into the other categories.

- Kiri nō (切り能, final plays) or oni mono (鬼物, demon plays) usually feature the shite in the role of monsters, goblins, or demons, and are often selected for their bright colors and fast-paced, tense finale movements.

Mood

- Mugen nō (夢幻能) usually deals with spirits, ghosts, phantasms, and supernatural worlds. Time is often depicted as passing in a non-linear fashion, and action may switch between two or more timeframes from moment to moment.

- Genzai nō (現在能), as mentioned above, depicts normal events of the everyday world. However, when contrasted with mugen instead of with the other four categories, the term encompasses a somewhat broader range of plays.

Style

- Geki nō (劇能) or drama plays are based around the advancement of plot and the narration of action.

- Furyū nō (風流能) or dance plays focus rather on the aesthetic qualities of the dances and songs which are performed.

Okina (or Kamiuta) is a unique play which combines dance with Shinto ritual. It is considered the oldest type of Noh play, and is probably the most often performed. It will generally be the opening work at any programme or festival.

Sources

The Tale of the Heike, a medieval tale of the rise and fall of the Taira clan, originally sung by blind monks who accompanied themselves on the biwa, is an important source of material for Noh (and later dramatic forms), particularly warrior plays. Another major source is The Tale of Genji, an eleventh century work of profound importance to the later development of Japanese culture. Authors also drew on Nara and Heian period Japanese classics, and Chinese sources.

Some famous plays

- For a more comprehensive list, see List of Noh plays: A-M N-Z.

- Plays with a separate article are listed here.

The following categorization is that of the Kanze school.

| Name | Kanji | Meaning | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aoi no Ue | 葵上 | Lady Aoi | 4 (misc.) |

| Aya no Tsuzumi | 綾鼓 | The Damask Drum | 4 (misc.) |

| Dōjōji | 道成寺 | Dōjōji | 4 (misc.) |

| Hagoromo | 羽衣 | The Feather Mantle | 3 (woman) |

| Izutsu | 井筒 | The Well Cradle | 3 (woman) |

| Kagekiyo | 景清 | Kagekiyo | 4 (misc.) |

| Kanawa | 鉄輪 | The Iron Ring/Crown | 4 (misc.) |

| Kumasaka | 熊坂 | Kumasaka/The Robber | 5 (demon) |

| Matsukaze | 松風 | The Wind in the Pines | 3 (woman) |

| Nonomiya | 野宮 | The Shrine in the Fields | 3 (woman) |

| Sekidera Komachi | 関寺小町 | Komachi at Sekidera | 3 (woman) |

| Semimaru | 蝉丸 | Semimaru | 4 (misc.) |

| Shakkyō | 石橋 | Stone Bridge | 5 (demon) |

| Shōjō | 猩々 | The Tippling Elf | 5 (demon) |

| Sotoba Komachi | 卒都婆小町 | Komachi at the Gravepost | 3 (woman) |

| Takasago | 高砂 | At Takasago | 1 (deity) |

| Tsunemasa | 経政 | Tsunemasa | 2 (warrior) |

| Yorimasa | 頼政 | Yorimasa | 2 (warrior) |

| Yuya | 熊野 | Yuya | 3 (woman) |

Performance elements

Noh performance combines a variety of elements into a stylistic whole, with each particular element the product of generations of refinement according to the central Buddhist, Shinto, and minimalist aspects of Noh's aesthetic principles.

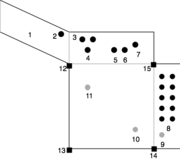

Stage

The traditional Noh stage consists of a pavilion whose architectural style is derived from that of the traditional kagura stage of Shinto shrines, and is normally composed almost entirely of hinoki (Japanese cypress) wood. The four pillars are named for their orientation to the prominent actions during the course of the play: the waki-bashira in the front, right corner near the waki's standing point and sitting point; the shite-bashira in the rear, left corner, next to which the shite normally performs; the fue-bashira in the rear, right corner, closest to the flute player; and the metsuke-bashira, or "looking-pillar", so called because the shite is typically faced toward the vicinity of the pillar.

The floor is polished to enable the actors to move in a gliding fashion, and beneath this floor are buried giant pots or bowl-shaped concrete structures to enhance the resonant properties of the wood floors when the actors stomp heavily on the floor. As a result, the stage is elevated approximately three feet above the ground level of the audience.

The only ornamentation on the stage is the kagami-ita, a painting of a pine-tree at the back of the stage. The two most common beliefs are that it represents either a famous pine tree of significance in Shinto at the Kasuga Shrine in Nara, or that it is a token of Noh's artistic predecessors which were often performed to a natural backdrop.

Another unique feature of the stage is the hashigakari, the narrow bridge to the right of the stage that the principal actors use to enter the stage. This would later evolve into the hanamichi in kabuki.

All stages which are solely dedicated to Noh performances also have a hook or loop in ceiling, which exists only to lift and drop the bell for the play Dōjōji. When that play is being performed in another location, the loop or hook will be added as a temporary fixture.

Costumes

The garb worn by actors is typically adorned quite richly and steeped in symbolic meaning for the type of role (e.g. thunder gods will have hexagons on their clothes while serpents have triangles to convey scales). Costumes for the shite in particular are extravagant, shimmering silk brocades, but are progressively less sumptuous for the tsure, the wakizure, and the aikyōgen.

For centuries, in accordance with the vision of Zeami, Noh costumes emulated the clothing that the characters would genuinely wear, whether that be the formal robes of a courtier or the street clothing of a peasant or commoner. It was not until the late sixteenth century that stylized Noh costumes following certain symbolic and stylistic conventions became the norm[4].

The musicians and chorus typically wear formal montsuki kimono (black and adorned with five family crests) accompanied by either hakama (a skirt-like garment) or kami-shimo, a combination of hakama and a waist-coat with exaggerated shoulders (see illustrations). Finally, the stage attendants are garbed in virtually unadorned black garments, much in the same way as stagehands in contemporary Western theater.

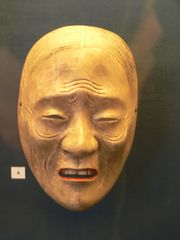

Masks

The masks in Noh (能面 nō-men or 面 omote, feature) all have names. They are made out of materials such as clay, dry lacquer, cloth, paper, and wood.

Usually only the shite, the main actor, wears a mask. However, in some cases, the tsure may also wear a mask, particularly for female roles. The Noh masks portray female or nonhuman (divine, demonic, or animal) characters. There are also Noh masks to represent youngsters or old men. On the other hand, a Noh actor who wears no mask plays a role of an adult man in his twenties, thirties, or forties. The side player, the waki, wears no mask either.

Several types of masks, in particular those for female roles, are designed so that slight adjustments in the position of the head can express a number emotions such as fear or sadness due to the variance in lighting and the angle shown towards the audience. With some of the more extravagant masks for deities and monsters, however, it is not always possible to convey emotion. Usually, however, these characters are not frequently called to change emotional expression during the course of the scene, or show emotion through larger body language.

The rarest and most valuable Noh masks are not held in museums even in Japan, but rather in the private collections of the various "heads" of Noh schools; these treasures are usually only shown to a select few and only taken out for performance on the rarest occasions. This does no substantial harm to the study and appreciation of Noh masks, as tradition has established a few hundred standard mask designs, which can further be categorized as being one of about a dozen different types.

Props

The most commonly used prop in Noh is the fan, as it is carried by all performers regardless of role. Chorus singers and musicians may carry their fan in hand when entering the stage, or carry it tucked into the obi. In either case, the fan is usually placed at the performer's side when he or she takes position, and is often not taken up again until leaving the stage.

Several plays have characters who wield mallets, swords, and other implements. Nevertheless, during dance sequences, the fan is typically used to represent any and all hand-held props, including one such as a sword which the actor may have tucked in his sash or ready at hand nearby.

When hand props other than fans are used, they are usually introduced or retrieved by stage attendants who fulfill a similar role to stage crew in contemporary theater. Like their Western counterparts, stage attendants for Noh traditionally dress in black, but unlike in Western theater they may appear on stage during a scene, or may remain on stage during an entire performance, in both cases in plain view of the audience.

Stage properties in Noh including the boats, wells, altars, and the aforementioned bell from Dōjōji, are typically carried onto the stage before the beginning of the act in which they are needed. These props normally are only outlines to suggest actual objects, although the great bell, a perennial exception to most Noh rules for props, is designed to conceal the actor and to allow a costume change during the aikyogen interlude.

Chant and Music

Noh theatre is accompanied by a chorus and a hayashi ensemble (Noh-bayashi 能囃子). Noh is a chanted drama, and a few commentators have dubbed it "Japanese opera." However, the singing in Noh involves a limited tonal range, with lengthy, repetitive passages in a narrow dynamic range. Clearly, melody is not at the center of Noh singing. Still, texts are poetic, relying heavily on the Japanese seven-five rhythm common to nearly all forms of Japanese poetry, with an economy of expression, and an abundance of allusion.

It is important to note that the chant is not always performed "in character"; that is, sometimes the actor will speak lines or describe events from the perspective of another character or even a disinterested narrator. Far from breaking the rhythm of the performance, this is actually in keeping with the other-worldy feel of many Noh plays, especially those characterized as mugen.

Noh hayashi ensemble consists of four musicians, also known as the "hayashi-kata". There are three drummers, which play the shime-daiko, ōtsuzumi (hip drum), and kotsuzumi (shoulder drum) respectively, and a shinobue flautist.

Jo, Ha, Kyū

One of the most subtle performance elements of Noh is that of Jo-ha-kyū, which originated as the three movements of courtly gagaku. However, rather than simply dividing a whole into three parts, within Noh the concept incorporates not only the play itself, but the songs and dances within the play, and even the individual steps, motions, and sounds that actors and musicians make. Furthermore, from a higher perspective, the entire traditional Noh program of five plays also manifests this concept, with the first type play being the jo, the second, third, and fourth plays the ha (with the second play being referred to as the jo of the ha, the third as the ha of the ha, and the fourth as the kyū of the ha), and finally the fifth play the kyū. In general, the jo component is slow and evocative, and ha component or components detail transgression or the disordering of the natural way and the natural world, and the kyū resolves the element with haste or suddenness (note, however, that this only means kyū is fast in comparison with what came before it, and those unfamiliar with the concepts of Noh may not even realize the acceleration occurred).

Actors

There are about 1500 professional Noh actors in Japan today, and the art form continues to thrive. Actors begin their training as young children, traditionally at the age of three. Historically, the performers were exclusively male. In the modern day, a few women (many daughters of established Noh actors) have begun to perform professionally. Many people also study Noh on an amateur basis. While the field of Noh performance is extremely codified with an emphasis on tradition rather than innovation, some performers do compose new plays or revive historical ones that are not a part of the standard repertoire. Works blending Noh with other theatrical traditions have also been produced.

The five extant schools of Noh shite acting are the Kanze (観世), Hōshō (宝生), Komparu (金春), Kita (喜多), and Kongō (金剛) schools. Each school has a leading family known as the sōke, and the head of each family is entitled to create new plays or edit existing songs.

The society of Noh strictly protects the traditions passed down from their ancestors (see iemoto). However, several secret documents of the Kanze school written by Zeami, and of the Komparu school written by Komparu Zenchiku have been diffused throughout the community of scholars of Japanese theater.

Actors normally follow a strict progression through the course of their lives from roles considered the most basic to those considered the most complex or difficult; the role of Yoshitsune in Funa Benkei is one of the most prominent roles a child actor performs in Noh.

Influence in the West

Western artists influenced by Noh include:

Theatre practitioners

- Bertolt Brecht

- Peter Brook

- Jacques Lecoq

- Jacques Copeau

- Eugenio Barba

- Jerzy Grotowski

- Heiner Müller

- Eugene O'Neill

- Osvobozené divadlo

Composers

- William Henry Bell

- Benjamin Britten

- Carlo Forlivesi

- Olivier Messiaen

- Karlheinz Stockhausen

- Iannis Xenakis

- David Byrne

Poets

Aesthetic terminology

Zeami and Zenchiku describe a number of distinct qualities that are thought to be essential to the proper understanding of Noh as an art form.

- Hana (花, flower): the true Noh performer seeks to cultivate a rarefied relationship with his audience similar to the way that one cultivates flowers. What is notable about hana is that, like a flower, it is meant to be appreciated by any audience, no matter how lofty or how coarse his upbringing. Hana comes in two forms. Individual hana is the beauty of the flower of youth, which passes with time, while "true hana" is the flower of creating and sharing perfect beauty through performance.

- Yūgen (幽玄): an aesthetic term used to describe much of the art of the 13th and 14th centuries in Japan, but used specifically in relation to Noh to mean the profound beauty of the transcendental world, including mournful beauty involved in sadness and loss.

- Kokoro or shin (both 心): Defined as "heart," "mind," or both. The kokoro of noh is that which Zeami speaks of in his teachings, and is more easily defined as "mind." To develop hana the actor must enter a state of no-mind, or mushin.

- Rōjaku (老弱): the final stage of performance development of the Noh actor, in which as an old man he eliminates all unnecessary action or sound in his performance, leaving only the true essence of the scene or action being imitated.

- Myō (妙): the "charm" of an actor who performs flawlessly and without any sense of imitation; he effectively becomes his role.

- Monomane (物真似, imitation or mimesis): the intent of a Noh actor to accurately depict the motions of his role, as opposed to purely aesthetic reasons for abstraction or embellishment. Monomane is sometimes contrasted with yūgen, although the two represent endpoints of a continuum rather than being completely separate.

- Kabu-isshin (歌舞一心, "song-dance-one heart"): the theory that the song (including poetry) and dance are two halves of the same whole, and that the Noh actor strives to perform both with total unity of heart and mind.

See also

- Iemoto

- Kitayama Bunka

- Higashiyama Bunka

- Shuhari

References

- ↑ "Nogaku". Dictionary.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Nogaku.

- ↑ "Enjoying Noh and Kyōgen". The Nohgaku performers' association. p. 3. http://www.nohgaku.or.jp/download/guide_english.pdf.

- ↑ Ortolani, Benito. The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism. Princeton University Press. p. 132. ISBN 0691043337. http://books.google.com/books?id=ge8cWl8OT3gC&pg=PA132&dq=mugen-no+Genzai-no+waki-no#v=onepage&q=mugen-no%20Genzai-no%20waki-no&f=false.

- ↑ Morse, Anne Nishimura, et al. MFA Highlights: Arts of Japan. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Publications, 2008. p109.

Bibliography

- James R. Brandon (editor). "Nō and kyōgen in the contemporary world." (foreword by Ricardo D. Trimillos) Honolulu : University of Hawaiʻi Press. 1997.

- Karen Brazell. Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays. New York: Columbia University Press. 1998.

- Eric Rath. The Ethos of Noh: Actors and Their Art. Harvard University Asia Center Press, 2004.

- Royall Tyler (ed. & trans.). Japanese Nō Dramas. London: Penguin Books. 1992 ISBN 0-14-044539-0

- Arthur Waley. Noh plays of Japan. Tuttle Shokai Inc. 2009 ISBN-10 4805310332 ISBN-13 978-4805310335

External links

- Noh Stories in English Ohtsuki Noh Theatre Foundation

- Nō Plays -Translations of thirteen Noh plays- Japanese Text Initiative, University of Virginia Library

- Virtual Reality and Virtual Irreality On Noh-Plays and Icons

- "Noh & Kyogen". Japan Arts Council. http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/unesco/noh/en/index.html.

- Page on the variable expressions of Noh masks

- Noh plays Photo Story and Story Paper