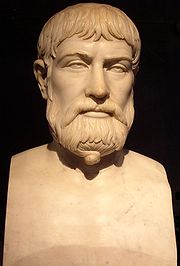

Pindar

Pindar (Greek: Πίνδαρος, Pindaros; Latin: Pindarus) (ca. 522–443 BC), was an Ancient Greek lyric poet. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, Pindar is the one whose work is best preserved. Quintilian described him as "by far the greatest of the nine lyric poets, in virtue of his inspired magnificence, the beauty of his thoughts and figures, the rich exuberance of his language and matter, and his rolling flood of eloquence".[1]

|

However, not all the ancients shared Quintilian's enthusiasm. The Athenian comic playwright Eupolis is said to have remarked that the poems of Pindar "are already reduced to silence by the disinclination of the multitude for elegant learning".[2]

Pindar's 'elegant learning' has often discouraged modern interest as well, particularly up until the end of the nineteenth century. The discovery in 1896 of some poems by his rival Bacchylides then allowed for useful comparisons and it was found that some idiosyncrasies, evident in Pindar's Victory Odes, were typical of the genre rather than of the poet himself. From then on, the brilliance of Pindar's poetry began to be more widely appreciated by modern scholars and yet there are still peculiarities in his style that challenge the casual reader and he continues to be a largely unread, even if much admired poet.[3]

Pindar is the first Greek poet whose works reflect extensively on the nature of poetry and on the poet's role.[4] Like other poets of the Archaic Age, he reveals a deep sense of the vicissitudes of life and yet, unlike them, he also articulates a passionate faith in what men can achieve by the grace of the gods, most famously expressed in his conclusion to one of his Victory Odes:[5]

Pindar's poetry illustrates the beliefs and values of Archaic Greece at the dawn of the classical period.[8]

Biography

Sources

Five ancient sources contain all the recorded details of Pindars life. One of them is a short biography that was discovered in 1961 on an Egyptian papyrus dating from at least 200 AD (P.Oxy.2438).[9] The other four are historic collections that weren't finalized until some 1600 years after Pindar's death:

- Commentaries on Pindar by Eustathius of Thessalonica;

- Vita Vratislavensis, found in a manuscript at Breslau, author unknown;

- a text by Thomas Magister;

- some meagre writings attributed to the lexicographer Suidas.

Although these sources are based on a much older literary tradition, going as far back as Chamaeleon of Heraclea in the 4th century BC, they are widely viewed with scepticism today: much of the ancient material is clearly fanciful.[10][11] Scholars both ancient and modern have turned to Pindar's own work – his victory odes in particular – as a source of biographical information: many of the poems can be dated accurately and they often touch on historic events. However even the poems began to seem unreliable sources after the 1962 publication of Elroy Bundy's ground-breaking work Pindarica. For Bundy, and for a generation of scholars influenced by him, the odes do not commemorate Pindar's personal thoughts and feelings but are public statements "dedicated to the single purpose of eulogizing men and communities."[12] It seemed that scholars pre-1962 had been seduced by a "fatal conjunction" of historicism and Romanticism[13] and yet the pendulum of intellectual fashion has now swung back at least some of the way: a limited and cautious use of the poems for biographical purposes is considered acceptable again.[14][15]

The biography in this article is an amalgam of old and new approaches – it is naive in its reliance on the odes as biographical sources and it even includes a few clearly fanciful elements from ancient accounts.[16][17] Some of the problematic aspects of this traditional approach are then illustrated in notes at the end of relevant paragraphs. Moreover, the biography progresses backwards in time as an example of Pindar's unique literary methods – he often demonstrated particular themes by narrating episodes from traditional myths, sometimes in reverse chronological order.

Post mortem

Greeks long cherished the memory of Pindar. His house in Thebes became one of the city's landmarks, especially after Alexander The Great demolished every other house there — he left the poet's house spectacularly intact out of gratitude for some verses praising his ancestor, king Alexander I of Macedon.[18] Some of Pindar's verses became a scenic attraction in Lindos, Rhodes, where they were inscribed in letters of gold on a temple wall. At Delphi, the priests of Apollo exhibited an iron chair on which the poet used to sit during the festival of the Theoxenia. "Let Pindar the poet go unto the supper of the gods!" they intoned every night while closing the temple doors (he had once been elected to the priesthood there). One of his female relatives claimed that he had dictated to her some verses in honour of Persephone — after he had been dead for several days!

Death and old age

Pindar lived to about eighty years of age and died sometime around 440 BC while attending a festival at Argos. His ashes were taken back home to Thebes by his musically-gifted daughters, Eumetis and Protomache. Nothing is recorded about his wife and son except their names, Megacleia and Daiphantus. In one of his last odes (Pythian 8), celebrating a victory by an athlete from Aegina, Pindar reveals that he lived near a shrine to the oracle Alcmaeon and that he stored some of his wealth there. He says in the same ode that he had recently received a prophecy from Alcmaeon during a journey to Delphi — "...he met me and proved the skills of prophecy that all his race inherit"[19] — but he doesn't reveal what the long-dead prophet said to him nor in what form he appeared.

- Note: Pindar doesn't necessarily refer to himself when he uses the first person singular. A large proportion of his 'I' statements seem to be generic, indicating somebody engaged in the role of a singer i.e. a 'bardic' I. Other 'I' statements articulate values typical of the audience and some are spoken on behalf of the subject celebrated in the poem.[20] The 'I' that received the prophecy in Pythian 8 might thus have been the athlete from Aegina, not Pindar. In that case, the prophecy probably concerned his victory in the Pythian Games and the property stored at the shrine was just a votive offering.[21]

Fame as a poet involved Pindar in the world of Greek politics, drawing him into conflicting loyalties. Athens, for example, was the dominant force in Greece throughout his poetic career and it happened to be a long-term rival both of his home city, Thebes, and of the island state Aegina, whose leading citizens commissioned about a quarter of his Victory Odes. There is no open condemnation of the Athenians in any of Pindar's poems but sometimes he smuggles in some criticism. For example, the victory ode mentioned above (Pythian 8) covertly celebrates a recent defeat of Athens by Thebes at the Battle of Coronea (447 BC), represented imaginatively as the downfall of the giants Porphyrion and Typhon[22] and the poem ends with a prayer for Aegina's freedom (long threatened by Athenian ambitions).

- Note: Covert allusions to rivalry with Athens (traditionally located in odes such as Pythian 8, Nemean 8 and Isthmian 7) are now considered highly unlikely even by scholars who allow for some biographical and historical interpretations of the poems.[23]

Middle age

Pindar seems to have used his odes to advance his personal interests and those of his friends.[24] In 462 BC he composed two odes in honour of Arcesilas, king of Cyrene, (Pythians 4 and 5), pleading for the return from exile of a friend, Demophilus. In the latter ode Pindar proudly mentions his own ancestry, which he shared with the king, as an Aegeid or descendent of Aegeus, the legendary king of Athens. The clan was influential in many parts of the Greek world, having intermarried with ruling families in Thebes, in Lacedaemonia and in cities that claimed Lacedaemonian descent, such as Cyrene and Thera. The historian Herodotus considered the clan important enough to deserve mention (Histories IV.147). Membership in the clan contributed to Pindar's success as the poet of an international elite and it informed his political views, marked by a conservative preference for oligarchic governments of the Doric kind.

- Note: Pindar's claim to be an Aegeid may be doubted on the grounds that 'I' statements do not necessarily refer to the poet. On the other hand, the Aegeid clan did have a branch in Thebes and it is possible that Pindar's reference to "my ancestors" in Pythian 5 could have been spoken on behalf of both Arcesilas and Pindar – the poet might have used such ambivalences to establish a personal link with his patrons.[25]

He was possibly the Theban proxenos or consul for Aegina and/or Molossia, as indicated in another of his odes, Nemean 7,[26] in which he glorifies Neoptolemus, a national hero of both Aegina and Molossia. According to tradition, Neoptolemus died in a disgraceful fight with priests at the temple in Delphi over their share of some sacrificial meat. Pindar diplomatically glosses over this. The ode ends mysteriously with an ernest protestation of innocence – "But shall my heart never admit that I with words none can redeem dishonoured Neoptolemus" – and possibly this was said in response to anger among Aeginetans and/or Molossians over his portrayal of Neoptolemus in an earlier poem, Paean 6, which had been commissioned by the priests at Delphi and which depicted the hero's death in traditional terms, as divine retribution for his past crimes.

- Note: This biographical interpretation of Nemean 7 is doubted on a variety of grounds: it is largely based on some marginal comments by scholiasts yet Pindaric scholiasts are generally unreliable; it has no relevance to the poem as a song of praise for the victor of an athletic contest; the fact that Pindar gave different versions of the one myth simply reflects the needs of different genres and does not necessarily indicate a personal dilemma.[27] Nemean 7 in fact is the most controversial and obscure of Pindar's victory odes and scholars ancient and modern have exercised ingenuity and imagination in their attempts to explain it, so far without agreed success.[28]

In his first Pythian ode, composed in 470 BC in honour of the Sicilian tyrant Hieron, Pindar celebrated a series of stunning victories by Greeks against foreign invaders: Athenian and Spartan-led victories against Persia at Salamis and Plataea, and victories by the western Greeks led by Theron of Acragas and by Hieron against the Carthaginians and Etruscans at the battles of Himera and Cumae. Such celebrations were not appreciated by his fellow Thebans: they had sided with the Persians and they had incurred many losses and privations as a result of their defeat. His praise of Athens with such epithets as bullwark of Hellas (fragment 76) and city of noble name and sunlit splendour (Nemean 5) once induced the authorities in Thebes to fine him 5000 drachmae, to which the astute Athenians are said to have responded with a gift of 10000 drachmae. According to another account,[29] the Athenians even made him their proxenus or consul in Thebes, though this claim is now largely discredited.[30] His association with the fabulously rich Hieron was another source of annoyance at home. It was probably in response to Theban sensitivities over this issue that he denounced the rule of tyrants (i.e. rulers like Hieron) in an ode composed shortly after a visit to Hieron's sumptuous court in 476–75 BC (Pythian 11).[31]

- Note: Pindar's actual phrasing in Pythian 11 was "I deplore the lot of tyrants" and though this was traditionally interpreted as an apology for his dealings with Sicilian tyrants like Hieron, an alternative date for the ode led some scholars to conclude that it was in fact a covert reference to the tyrannical behaviour of the Athenians, and yet this interpretation too is ruled out if we accept the earlier note about covert references. According to yet another interpretation, Pindar is simply delivering a formulaic warning to the successful athlete to avoid hubris.[32]

Lyric verse was conventionally accompanied by music and dance and Pindar himself wrote the music and choreographed the dances for his victory odes. Sometimes he trained the performers at his home in Thebes and sometimes he trained them at the venue where they performed. Commissions took him to all parts of the Greek world – to the Panhellenic festivals in mainland Greece (Olympia, Delphi, Corinth and Nemea), westwards to Sicily, eastwards to the seaboard of Asia Minor, north to Macedonia and Abdera (Paean 2) and south to Cyrene on the African coast. Other poets attended the same venues and vied with him for the favours of patrons. His poetry sometimes reflects this rivalry. Thus for example Olympian 2 and Pythian 2, composed in honour of the Sicilian tyrants Theron and Hieron following his visit to their courts in 476–75 BC, refer respectively to ravens and an ape, apparently signifying rivals engaged in a campaign of smears against him – possibly even the celebrated poets Simonides and his nephew Bacchylides.[33] Pindar's original treatment of narrative myth, often relating events in reverse chronological order, is said to have been a favourite target for criticism.[34] Simonides was known to charge high fees for his work and Pindar is said to have alluded to this in Isthmian 2, where he refers to the Muse as "a hireling journeyman".

- Note: It was assumed by ancient sources that Pindar's odes were performed by a chorus – this has been challenged by some modern scholars who argue that the odes were in fact performed solo.[35] It is not known how commissions were arranged, nor if the poet travelled widely: even when poems include statements like "I have come", it is not certain that this was meant literally.[36] Uncomplimentary references to Bacchylides and Simonides were found by scholiasts but there is no reason to accept their interpretation of the odes.[37] In fact some scholars have interpreted the allusions to fees in Isthmian 2 as a request by Pindar for payment of fees owed to himself.[38]

Adulthood to infancy

The early to middle years of Pindar's career coincided with the Persian invasions of Greece in the reigns of Darius and Xerxes. During the invasion in 480/79 BC, when Pindar was almost forty years old, Thebes was occupied by Xerxes' general, Mardonius, with whom many Theban aristocrats subsequently perished at the Battle of Plataea. It is possible that Pindar spent much of this time at Aegina. His choice of residence during the earlier invasion in 490 BC is not known but he was able to attend the Pythian Games for that year, where he first met the Sicilian prince, Thrasybulus, nephew of Theron of Acragas. Thrasybulus had driven the winning chariot and he and Pindar were to form a lasting friendship, paving the way for his subsequent visit to Sicily.

Pindar was about twenty years old in 498 BC when he was commissioned by the ruling family in Thessaly to compose his first victory ode (Pythian 10). He studied the art of lyric poetry in Athens, where his tutor was Lasos of Hermione, and he is also said to have received some helpful criticism from Corinna. It is reported moreover that he was stung on the mouth by a bee in his youth and this was the reason he became a poet of honey-like verses (an identical fate has been ascribed to other poets of the archaic period). He was probably born in 522 BC or 518 BC (the 65th Olympiad) in Cynoscephalae, a village in Boeotia, not far from Thebes. His father's name is variously given as Daiphantus, Pagondas or Scopelinus and his mother's name was Cleodice.[10]

Works

Pindar's original and strongly individual genius is apparent in all his extant compositions but, unlike Simonides and Stesichorus for example, he created no new lyrical genres.[39] He was however innovative in his employment of the genres he inherited – for example, in one of his victory odes (Olympian 3), he announces his invention of a new type of musical accompaniment, combining lyre, flute and human voice (though our knowledge of Greek music is too sketchy to allow us to understand the full nature of this innovation).[40] He probably spoke Boeotian Greek but he composed in a literary language fairly typical of archaic Greek poetry, relying on Doric dialect more consistently than his rival Bacchylides, for example, but less insistently than Alcman. There is an admixture of other dialects, especially Aeolic and epic forms, and there is an occasional use of some Boeotian words.[41] He composed choral songs of several types which, according to a Late Antique biographer, were subsequently grouped into seventeen books by scholars at the Library of Alexandria. They were, by genre:[42]

- 1 book of humnoi – "hymns"

- 1 book of paianes – "paeans"

- 2 books of dithuramboi – "dithyrhambs"

- 2 books of prosodia – "processionals"

- 3 books of parthenia – "songs for maidens"

- 2 books of huporchemata – "songs for light dances"

- 1 book of enkomia – "songs of praise"

- 1 book of threnoi – "laments"

- 4 books of epinikia – "victory odes"

Of this vast and varied corpus, only the epinikia — odes written to commemorate athletic victories — survive in complete form; the rest survive only by quotations in other ancient authors or from papyrus scraps unearthed in Egypt. Even in fragmentary form, however, the various genres reveal the same complexity of thought and language that are found in the victory odes.[43]

Victory odes

Almost all Pindar's victory odes are celebrations of triumphs gained by competitors in Panhellenic festivals such as the Olympian Games. The establishment of these athletic and musical festivals was among the greatest achievements of the Greek aristocracies. Even in the fifth century, when there was an increased tendency towards professionalism, they were predominantly aristocratic assemblies, reflecting the expense and the leisure needed to attend such events either as a competitor or spectator. Attendance was an opportunity for display and self-promotion, and the prestige of victory, requiring commitment in time and/or wealth, went far beyond anything that accrues to athletic victories today, even in spite of the modern preoccupation with sport.[44] Pindar's odes capture something of the prestige and the aristocratic grandeur of the moment of victory, as in this stanza from one of his Isthmian Odes, here translated by Geoffrey S. Conway:

-

-

-

-

- If ever a man strives

-

- With all his soul's endeavour, sparing himself

- Neither expense nor labour to attain

- True excellence, then must we give to those

- Who have achieved the goal, a proud tribute

-

- Of lordly praise, and shun

- All thoughts of envious jealousy.

-

- To a poet's mind the gift is slight, to speak

- A kind word for unnumbered toils, and build

- For all to share a monument of beauty. (Isthmian I, antistrophe 3)[45]

-

-

His victory odes are grouped into four books named after the Olympian, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games – Panhellenic festivals held respectively at Olympia, Delphi, Corinth and Nemea. This reflects the fact that most of the odes were composed in honour of boys, youths and men who had recently enjoyed victories in athletic (and sometimes musical) contests at those festivals. In a few odes, however, much older victories and even victories in lesser games are sometimes celebrated, often being used as a pretext for addressing other issues or achievements. For example, Pythian 3, composed in honour of Hieron of Syracuse, briefly mentions an old victory he had once enjoyed at the Pythian Games, but it is actually intended to console him for his chronic illness. Nemean 9 and Nemean 10 celebrate victories in games at Sicyon and Argos, and Nemean 11 celebrates a victory in a municipal election on Tenedos (though it includes mention of some obscure athletic victories). These three odes are the final odes in the Nemean book of odes and there is a reason for their inclusion there. In the original manuscripts, the four books of odes were arranged in the order of importance assigned to the festivals, with the Nemean festival, considered least important, coming last. Any victory odes that lacked the aura of a Panhellenic subject were then bundled together at the end of the book of Nemean odes.[40]

Style

As mentioned in the introduction, Pindar's poetic style is unique and highly individualised even when the peculiarities of the genre are set aside. The odes typically feature a grand and arresting opening, often with architectural metaphor or a resounding invocation to a place or goddess. He makes rich use of decorative language and florid compound adjectives.[46] Sentences are compressed to the point of obscurity, unusual words and periphrases give the language an esoteric quality, transitions in meaning often seem erratic, and images seem to burst out – it's a style that baffles reason and which makes his poetry vivid and unforgettable.[47]

"Pindar's power does not lie in the pedigrees of ... athletes, ... It lies in a splendour of phrase and imagery that suggests the gold and purple of a sunset sky." – F.L. Lucas[48]

"He has that force of imagination which can bring clear-cut and dramatic figures of gods and heroes into vivid relief...he has that peculiar and inimitable splendour of style which, though sometimes aided by magnificent novelties of diction, is not dependent on them, but can work magical effects with simple words; he has also, at frequent moments, a marvellous swiftness, alike in the succession of images, and in the transitions from thought to thought; and his tone is that of a prophet who can speak with a voice as of Delphi." – Richard Claverhouse Jebb[49]

His odes were animated by..."one burning glow which darted out a shower of brilliant images, leapt in a white-hot spark across gaps unbridgeable by thought, passed through a commonplace leaving it luminous and transparent, melted a group of heterogeneous ideas into a shortlived unity and, as suddenly as a flame, died." - Gilbert Highet[50]

Such qualities can be found, for example, in this stanza from Pythian 2, composed in honour of Hieron:

-

-

- God achieves all his purpose and fulfills

- His every hope, god who can overtake

- The winged eagle, or upon the sea

- Outstrip the dolphin; and he bends

- The arrogant heart

- Of many a man, but gives to others

- Outstrip the dolphin; and he bends

- Eternal glory that will never fade.

- Now for me is it needful that I shun

-

- The fierce and biting tooth

-

- Of slanderous words. For from old have I seen

- Sharp-tongued Archilochus in want and struggling,

-

- Grown fat on the harsh words

- Of hate. The best that fate can bring

-

- Is wealth joined with the happy gift of wisdom.[51][52]

-

The stanza begins with a universalizing movement, taking in the sky, sea, god and the human struggle for justice, then abruptly shifts to a darker, more allusive train of thought, featuring a highly individual, even eccentric condemnation of a renowned poet, Archilochus with curious phrasing such as Grown fat on the harsh words of hate. Archilochus took a sardonic and often humorous view of his own and other people's faults – a regrettable tendency from the viewpoint of Pindar, whose own persona is intensely earnest, preaching to high achievers like Hieron the need for moderation (wealth with wisdom) and submission to the divine will. The reference to the embittered poet appears to be Pindar's meditative response to some intrigues at Hieron's court, possibly by his personal rivals, condemned elsewhere as a pair of ravens (Olympian 2). The intensity of the stanza suggests that it is the culmination and climax of the poem. In fact, the stanza occupies the middle of Pythian 2 and the intensity is sustained throughout the poem from beginning to end. It is the sustained intensity of his poetry that Quintilian refers to above as a rolling flood of eloquence and Horace below refers to as the uncontrollable momentum of a river that has burst its banks. Longinus likens him to a vast fire[53] and Athenaeus refers to him as the great-voiced Pindar.[54]

Pindar's treatment of myth is another unique aspect of his style, often involving variations on the traditional stories.[55] Myths enabled him to develop the kind of themes and lessons that pre-occupied him – in particular mankind's exulted relation with the gods via heroic ancestors and, in contrast, the limitations and uncertainties of human existence – but sometimes the traditional stories were an embarrassment and they needed to be carefully edited, as for example: "Be still my tongue: here profits not / to tell the whole truth with clear face unveiled," (Nemean 5, epode 1); "Away, away this story! / Let no such tale fall from my lips! / For to insult the gods is a fool's wisdom," (Olympian 9, strophe 2); "Senseless, I hold it, for a man to say / the gods eat mortal flesh. / I spurn the thought," (Olympian 1, epode 2).[56] His mythical accounts are also edited for dramatic and graphic effects, usually unfolding through a few grand gestures against a background of large, often symbolic elements such as sea, sky, darkness, fire or mountain.[57]

Structure

Pindar's odes typically begin with an invocation to a god or the Muses, followed by praise of the victor and often of his family, ancestors and home-town. Then follows a narrated myth, usually occupying the central and longest section of the poem, exemplify a moral while also aligning the world of the poet and his audience with the world of gods and heroes.[58] The ode usually ends in more eulogies, as for example of trainers (if the victor is a boy), and of relatives who have won past events, as well as with prayers or expressions of hope for future success.[40] The event where the victory was gained is never described in detail but there is often some brief mention of the hard work needed to bring the victory about.

A lot of modern criticism is concerned with finding hidden structure or some unifying principle within the odes. 19th century criticism favoured 'gnomic unity' i.e. each ode is bound together by the kind of moralizing or philosophic vision typical of archaic Gnomic poetry. Later critics sought for unity in the way certain words or images are repeated and developed within any particular ode. For others, the odes really are just celebrations of men and their communities, in which the elements such as myths, piety and ethics are stock themes that the poet introduces without much real thought. Some have concluded that the requirement for unity is too modern to have informed Pindar's ancient approach to a traditional craft.[41]

The great majority of the odes are triadic in structure – i.e. stanzas are grouped together in threes as a lyrical unit. Each triad comprises two stanzas identical in length and meter (called 'strophe' and 'antistrophe') and a third stanza (called an 'epode'), differing in length and meter but rounding off the lyrical movement in some way. The shortest odes comprise a single triad, the largest (Pythian 4) comprises thirteen triads. Seven of the odes however are monostrophic (i.e. each stanza in the ode is identical in length and meter). The monostrophic odes seem to have been composed for victory marches or processions, whereas the triadic odes appear suited to choral dances.[40] Pindar's metrical rhythms are nothing like the simple, repetitive rhythms familiar to readers of English verse – typically the rhythm of any given line recurs infrequently (for example, only once every ten, fifteen or twenty lines). This adds to the aura of complexity that surrounds Pindar's work. In terms of meter, the odes fall roughly into two categories – about half are in dactylo-epitrites (a meter found for example in the works of Stesichorus, Simonides and Bacchylides) and the other half are in Aeolic metres based on iambs and choriambs.[41]

Chronological order

Modern editors (e.g. Snell and Maehler in their Teubner edition), have assigned dates, securely or tentatively, to Pindar's victory odes, based on ancient sources and other grounds. The date of an athletic victory is not always the date of composition but often serves merely as a terminus post quem. Many dates are based on comments by ancient sources who had access to published lists of victors, such as the Olympic list compiled by Hippias of Elis, and lists of Pythian victors made by Aristotle and Callisthenes. There were however no such lists for the Isthmian and Nemean Games[59] – Pausanias (6.13.8) complained that the Corinthians and Argives never kept proper records. The resulting uncertainty is reflected in the chronology below, with question marks clustered around Nemean and Isthmian entries, and yet it still represents a fairly clear general timeline of Pindar's career as an epinician poet. The code M denotes monostrophic odes (odes in which all stanzas are metrically identical) and the rest are triadic (i.e. featuring strophes, antistrophes, epodes):

| Date BC | Ode | Victor | Event | Focusing Myth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 498 | Pythian 10 | Hippocles of Thessaly | Boy's Long Foot-Race | Perseus, Hyperboreans |

| 490 | Pythian 6 (M) | Xenocrates of Acragas | Chariot-Race | Antilochus, Nestor |

| 490 | Pythian 12 (M) | Midas of Acragas | Flute-Playing | Perseus, Medusa |

| 488 (?) | Olympian 14 (M) | Asopichus of Orchomenos | Boys' Foot-Race | None |

| 486 | Pythian 7 | Megacles of Athens | Chariot-Race | None |

| 485 (?) | Nemean 2 (M) | Timodemus of Acharnae | Pancration | None |

| 485 (?) | Nemean 7 | Sogenes of Aegina | Boys' Pentathlon | Neoptolemus |

| 483 (?) | Nemean 5 | Pythias of Aegina | Youth's Pancration | Peleus, Hippolyta, Thetis |

| 480 | Isthmian 6 | Phylacides of Aegina | Pancration | Heracles, Telamon |

| 478 (?) | Isthmian 5 | Phylacides of Aegina | Pancration | Aeacids, Achilles |

| 478 | Isthmian 8 (M) | Cleandrus of Aegina | Pancration | Zeus, Poseidon, Thetis |

| 476 | Olympian 1 | Hieron of Syracuse | Horse-Race | Pelops |

| 476 | Olympians 2 & 3 | Theron of Acragas | Chariot-Race | 2.Isles of the Blessed 3.Heracles, Hyperboreans |

| 476 | Olympian 11 | Agesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris | Boys' Boxing Match | Heracles, founding of Olympian Games |

| 476 (?) | Nemean 1 | Chromius of Aetna | Chariot-Race | Infant Heracles |

| 475 (?) | Pythian 2 | Hieron of Syracuse | Chariot-Race | Ixion |

| 475 (?) | Nemean 3 | Aristocleides of Aegina | Pancration | Aeacides, Achilles |

| 474 (?) | Olympian 10 | Agesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris | Boys' Boxing Match | None |

| 474 (?) | Pythian 3 | Hieron of Syracuse | Horse-Race | Asclepius |

| 474 | Pythian 9 | Telesicrates of Cyrene | Foot-Race in Armour | Apollo, Cyrene |

| 474 | Pythian 11 | Thrasydaeus of Thebes | Boys' Short Foot-Race | Orestes, Clytemnestra |

| 474 (?) | Nemean 9 (M) | Chromius of Aetna | Chariot-Race | Seven Against Thebes |

| 474/3 (?) | Isthmian 3 & 4 | Melissus of Thebes | Chariot Race & Pancration | 3.None 4.Heracles, Antaeus |

| 473 (?) | Nemean 4 (M) | Timisarchus of Aegina | Boys' Wrestling Match | Aeacids, Peleus, Thetis |

| 470 | Pythian 1 | Hieron of Aetna | Chariot-Race | Typhon |

| 470 (?) | Isthmian 2 | Xenocrates of Acragas | Chariot-Race | None |

| 468 | Olympian 6 | Agesias of Syracuse | Chariot-Race with Mules | Iamus |

| 466 | Olympian 9 | Epharmus of Opous | Wrestling-Match | Deucalion, Pyrrha |

| 466 | Olympian 12 | Ergoteles of Himera | Long Foot-Race | Fortune |

| 465 (?) | Nemean Ode 6 | Alcimidas of Aegina | Boys' Wrestling Match | Aeacides, Achilles, Memnon |

| 464 | Olympian 7 | Diagoras of Rhodes | Boxing-Match | Tlepolemus |

| 464 | Olympian 13 | Xenophon of Corinth | Short Foot-Race & Pentathlon | Bellerephon, Pegasus |

| 462/1 | Pythian 4 & 5 | Arcesilas of Cyrene | Chariot-Race | 4.Argonauts 5.Battus |

| 460 | Olympian 8 | Alcimidas of Aegina | Boys' Wrestling-Match | Aeacus, Troy |

| 459 (?) | Nemean 8 | Deinis of Aegina | Foot-Race | Ajax |

| 458 (?) | Isthmian 1 | Herodotus of Thebes | Chariot-Race | Castor, Iolaus |

| 460 or 456 (?) | Olympian 4 & 5 | Psaumis of Camarina | Chariot-Race with Mules | 4.Erginus 5.None |

| 454 (?) | Isthmian 7 | Strepsiades of Thebes | Pancration | None |

| 446 | Pythian 8 | Aristomenes of Aegina | Wrestling-Match | Amphiaraus |

| 446 (?) | Nemean 11 | Aristagoras of Tenedos | Inauguration as Prytanis | None |

| 444 (?) | Nemean 10 | Theaius of Argos | Wrestling-Match | Castor, Pollux |

Horace's tribute

The great Latin poet, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, was an eloquent admirer of Pindar's style. He described it in these terms in one of his Sapphic poems, addressed to a friend, Julus Antonius:

-

-

-

- Pindarum quisquis studet aemulari,

- Iule, ceratis ope Daedalea

- nititur pennis vitreo daturus

- nomina ponto.

-

-

-

-

-

- monte decurrens velut amnis, imbres

- quem super notas aluere ripas,

- fervet immensusque ruit profundo

- Pindarus ore... (C.IV.II)

-

-

Translated by James Michie:[60]

-

-

-

- Julus, whoever tries to rival Pindar,

- Flutters on wings of wax, a rude contriver

- Doomed like the son of Daedalus to christen

- Somewhere a shining sea.

-

-

-

-

-

- A river bursts its banks and rushes down a

- Mountain with uncontrollable momentum,

- Rain-saturated, churning, chanting thunder –

- There you have Pindar's style...

-

-

Manuscripts, shreds and quotes

Pindar's verses have come down to the modern age in a variety of ways. Some are preserved only as fragments via quotes by ancient sources and papyri unearthed by archeologists, as at Oxyrhynchus – in fact the extant works of the other canonic lyric poets have survived only in this tattered form. Pindar's extant verses are unique in that the bulk of them – the victory odes – have been preserved through a manuscript tradition i.e. generations of scribes copying from earlier copies, possibly originating in a single archetypal copy and sometimes graphically demonstrated by modern scholars in the form of a stemma codicum, resembling a 'family tree'. Pindar's victory odes are preserved as a single corpus in just two manuscripts but various incomplete collections are located in many others, all dating from the mediaeval period. Some scholars have traced a stemma through these manuscripts, as for example Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, who inferred from them the existence of a common source or archetype dated no earlier than the second century AD, while others, such as C.M. Bowra, have argued that there are too many discrepancies between manuscripts to identify a specific lineage, even while accepting the existence of an archetype somewhere. Otto Schroeder identified two families of manuscripts but, following on the work of Polish-born classicist, Alexander Turyn,[61] Bowra rejected this also.[62] Different scholars have interpreted the extant manuscripts differently. Thus Bowra for example singled out seven manuscripts as his primary sources (see below), all more or less featuring errors and/or gaps due to loss of folios and careless copying, and one arguably characterized by the dubious interpolations of Byzantine scholars. These he cross-referenced then supplemented or verified by reference to other, still more doubtful manuscripts and even to some papyral fragments – a combination of sources on which he based his own edition of the odes and fragments. His general method of selection he defined as follows:

"Where all the codices agree, there perhaps the true reading shines out. Where however they differ, the preferred reading is that which best fits the sense, meter, scholia and grammatic conventions. Wherever moreover two or more readings of equal weight are found in the codices, I have chosen that which smacks most of Pindar. Yet this difficulty rarely occurs and in many places the true reading will be found if you examine and compare the language of the codices with that of other Greek poets and especially of Pindar himself."[63]

-

-

-

- Selected manuscripts – a sample of preferred sources (Bowra's choice, 1947)

-

-

| Code | Source | Format | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | codex Ambrosianus C 222inf. | paper 35x25.5 cm | 13–14th century | Comprises Olympian Odes 1–12, with some unique readings that Bowra considered reliable, and including scholia. |

| B | codex Vaticanus graeca 1312 | silk 24.3x18.4 cm | 13th century | Comprises odes Olympian 1 to Isthmian 8 (entire corpus), but with some leaves and verses missing, and includes scholia; Zacharias Callierges based his 1515 Roman eddition on it, possibly with access to the now missing material. |

| C | codex Parasinus graecus 2774 | silk 23x15 cm | 14th century | Comprises odes Olympian 1 to Pythian 5, including some unique readings but also with many Byzantine interpolations/conjectures (Turyn rejected this codex accordingly), and written in a careless hand. |

| D | codex Laurentianus 32, 52 | silk 27x19 cm | 14th century | Comprises odes Olympian 1 to Isthmian 8 (entire corpus), including a fragment (Frag. 1) and scholia, written in a careless hand. |

| E | codex Laurentianus 32, 37 | silk 24x17cm | 14th century | Comprises odes Olympian 1 to Pythian 12, largely in agreement with B, including scholia but with last page removed and replaced with paper in a later hand. |

| G | codex Gottingensis philologus 29 | silk 25x17 cm | 13th century | Comprises odes Olympian 2 to Pythian 12, largely in agreement with B (thus useful for comparisons), including Olympian 1 added in 16th century. |

| V | codex Parasinus graecus 2403 | silk 25x17 cm | 14th century | Comprises odes Olympian 1 to Nemean 4, including some verses from Nemean 6; like G, useful for supporting and verifying B. |

Influence and Legacy

Pindar was much read, quoted and copied during the Byzantine Era. For example, Christophoros Mytilenaios of the 11th century parodied a chariot race in his sixth poem employing explicit allusions to Pindar [64].

References

- ↑ Quintilian 10.1.61; cf. Pseudo-Longinus 33.5.

- ↑ Eupolis F366 Kock, 398 K/A, from Athenaeus 3a, (Deipnosophistae, epitome of book I)

- ↑ 'Some Aspects of Pindar's Style', Lawrence Henry Baker, The Sewanee Review Vol 31 No. 1 January 1923, page 100 preview

- ↑ 'A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets', Douglas E. Gerber, Brill 1997, page 261

- ↑ 'A Short History of Greek Literature', Jacqueline de Romilly, University of Chicage Press 1985, page 37

- ↑ 'Pindari Carmina Cum Fragmentis, Editio Altera', C. M. Bowra, Oxford University Press 1947, Pythia VIII, lines 95–7

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', translated by Geoffrey S. Conway, Everyman's University Library, 1972, page 144

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', translated by Geoffrey S. Conway, Everyman's University Library, 1972, Introduction page xv

- ↑ William H.Race, Pindar:Olympian Odes, Pythian Odes, Loeb Classical Library (1997), page 4

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 'A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets', Douglas E. Gerber, Brill (1997) page 253

- ↑ 'Pindar', Francis David Morice, Bibliobazaar, LLC (2009), page 211-15

- ↑ E.Bundy, Studia Pindarica, Berkeley (1962), page 35

- ↑ Lloyd-Jones, 'Pindar' in Proceedings of the British Academy 68 (1982), page 145

- ↑ Simon Hornblower, Thucydides and Pindar – Historical Narrative and the World of Epinikian Poetry, Oxford University Press (2004), pages 38, 59, 67 inter alia

- ↑ Bruno Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes, Oxford University Press (2005), pages 11–13

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', Geoffrey S. Conway, J.M.Dent and Sons (1972), Introduction and Notes

- ↑ 'Pindar', Francis David Morice, Bibliobazaar, LLC (2009) pages 31–8

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Alexander 11.6.; Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri 1.9.10

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', Geoffrey S. Conway, J.M.Dent and Sons (1972), page 142

- ↑ Bruno Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes, Oxford University Press (2005), pages 20

- ↑ Douglas E. Gerber, A Companion to the Greek lyric poets, Brill (1997) pages 268–9

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', Geoffrey S. Conway, John Dent and Sons (1972) page 138

- ↑ Charles Segal, 'Choral Lyric in the Fifth Century', in The Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek Literature, P.Easterling and B.Knox (eds), Cambridge University Press (1985), pages 231–2)

- ↑ T.K.Hubbard, 'Remaking Myth and Rewriting History: Cult Tradition in Pindar's Ninth Nemean', HSCP' 94 (1992), page 78

- ↑ Douglas E. Gerber, A Companion to the Greek lyric poets, Brill (1997) pages 270

- ↑ 'Thucydides and Pindar: Historical Narratives and the World of Epinikian Poetry', Simon Hornblower, Oxford University Press (2004), pages 177–80

- ↑ Ian Rutherford, Pindar's Paeans, Oxford University Press (2001), pages 321–22

- ↑ Leonard Woodbury, 'Neoptolemus at Delphi: Pindar, Nem.7.30ff, Pheonix Vol 33 No 2 (Summer 1979), pages 95–133

- ↑ Isocrates 15.166

- ↑ Simon Hornblower, Thucydides and Pindar – Historical Narrative and the World of Epinikian Poetry, Oxford University Press (2004), page 57 n.20

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', Geoffrey S. Conway, John Dent and Sons (1972) page 158

- ↑ Simon Hornblower, Thucydides and Pindar – Historical Narrative and the World of Epinikian Poetry, Oxford University Press (2004), page 59

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', Geoffrey S. Conway, John Dent and Sons (1972) pages 10, 88–9

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', Geoffrey S. Conway, John Dent and Sons (1972), Introduction page XIII

- ↑ Simon Hornblower, Thucydides and Pindar – Historical Narrative and the World of Epinikian Poetry, Oxford University Press (2004), page 16

- ↑ William H.Race, Pindar:Olympian Odes, Pythian Odes, Loeb Classical Library (1997) pages 10–11

- ↑ David Campbell, Greek Lyric III, Loeb Classical Library (1992), page 6

- ↑ 'The Odes of Pindar', Geoffrey S. Conway, John Dent and Sons (1972), page 239

- ↑ Richard Jebb, Bacchylides: the poems and fragments, Cambridge University Press 1905, page 41

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Geoffrey S. Conway, 'The Odes of Pindar', J.M. Dent and Sons (1972), page 17

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Douglas E. Gerber, 'A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets', Brill (1997) page 255

- ↑ M.M. Willcock: Pindar: Victory Odes (p. 3). Cambridge UP, 1995.

- ↑ Ewen Bowie, 'Lyric and Elegiac Poetry' in The Oxford History of the Classical World, J.Boardman, J.Griffin and O.Murray (eds), Oxford University Press (1986) page 110

- ↑ Antony Andrewes, Greek Society, Pelican Books (1971), pages 219–22

- ↑ Geoffrey S. Conway, 'The Odes of Pindar', J.M. Dent and Sons (1972), page 235

- ↑ Charles Segal, 'Choral Lyric in the Fifth Century', in The Cambridge History of Classical Greek Literature: Greek Literature, P.Easterling and B.Knox (eds), Cambridge University Press (1985), page 232

- ↑ Jacqueline de Romilly, 'A Short History of Greek Literature', University of Chicago Press (!985), page 38

- ↑ Lucas, F. L.. Greek Poetry for Everyman. Macmillan Company, New York. pp. 262.

- ↑ Richard Jebb, Bacchylides: the poems and fragments, Cambridge University Press 1905, page 41 digitalized Google version

- ↑ Gilbert Highet, The Classical Tradition, Oxford University Press (1949), page 225

- ↑ Geoffrey S. Conway, 'The Odes of Pindar', J.M.Dent and Sons (1972), pages 92–3

- ↑ C.M.Bowra, 'Pindari Carmina cum Fragmentis, editio altera', Oxford University Press (1968), Pythia II 49–56

- ↑ De Subl. 33.5

- ↑ Athenaeus 13.5.64c

- ↑ Ewen Bowie, 'Lyric and Elegiac Poetry' in The Oxford History of the Classical World, J.Boardman, J.Griffin and O.Murray (eds), Oxford University Press (1986) pages 107–8

- ↑ Geoffrey S. Conway, 'The Odes of Pindar', J.M.Dent and Sons (1972), pages 192, 54, 4 respectively

- ↑ Charles Segal, 'Choral Lyric in the Fifth Century', in The Cambridge History of Classical Greek Literature: Greek Literature, P.Easterling and B.Knox (eds), Cambridge University Press (1985), page 232

- ↑ Ewen Bowie, 'Lyric and Elegiac Poetry', in The Oxford History of the Classical World, eds. J.Boardman, J.Griffin and O.Murray (1986) page 108

- ↑ Bruno Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes, Oxford University Press (2005), page 25

- ↑ The Odes of Horace James Michie (translator), Penguin Classics 1976

- ↑ 'Alexander Turyn', Miroslav Marcovich, Gnomon, 54, Bd.,H.1 (1982) pp 97–98 [1]

- ↑ C.M. Bowra (ed),Pindari Carmina Cum Fragmentis, editio altera, Oxford University Press (1947), Praefatio iii–iv, vii

- ↑ C.M. Bowra (ed),Pindari Carmina Cum Fragmentis, editio altera, Oxford University Press (1947), Praefatio iv

- ↑ F. Lauritzen, Readers of Pindar and students of Mitylinaios, Byzantion 2010

Further reading

- Nisetich, Frank J., Pindar's Victory Songs. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: translations and extensive introduction, background and critical apparatus.

- Revard, Stella P., Politics, Poetics, and the Pindaric Ode 1450–1700, Turnhout, Brepols Publishers, 2010, ISBN 978-2-503-52896-0

- Race, W. H. Pindar. 2 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Bundy, Elroy L. (2006) [1962] (PDF). Studia Pindarica (digital version ed.). Berkeley, California: Department of Classics, University of California, Berkeley. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ucbclassics/bundy/. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- Barrett, W. S., Greek Lyric, Tragedy, and Textual Criticism: Collected Papers, edited M. L. West (Oxford & New York, 2007): papers dealing with Pindar, Stesichorus, Bacchylides and Euripides

- Kiichiro Itsumi, Pindaric Metre: 'The Other Half' (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

External links

- Works by Pindar at Project Gutenberg

- Selected odes, marked up to show selected rhetorical and poetic devices

- Olympian 1, read aloud in Greek, with text and English translation provided

- Pythian 3, translated by Frank J. Nisetich

- Pythian 8, 'Approaching Pindar' by William Harris (text, translation, analysis)

- Pindar by Gregory Crane, in the Perseus Encyclopedia

- Pindar's Life by Basil L. Gildersleeve, in Pindar: The Olympian and Pythian Odes

- Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Pindar, Olympian Odes, I, 1–64; read by William Mullen

- Perseus Digital Library Lexicon to Pindar, William J. Slater, De Gruyter 1969: scholarly dictionary for research into Pindar

Historic editions

- The Odes of Pindar translated into English with notes, D.W.Turner, A Moore, Bohm Classical Library (1852), digitalized by Google

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 11th ed. 1911 Vol.21 'Pindar'

- Pindar – translations and notes by Reverend C.A.Wheelwright, printed by A.J.Valpy, M.A., London (1830): digitalized by Google

|

|||||