Printmaking

Printmaking is the process of making artworks by printing, normally on paper. Printmaking normally covers only the process of creating prints with an element of originality, rather than just being a photographic reproduction of a painting. Except in the case of monotyping, the process is capable of producing multiples of the same piece, which is called a 'print'. Each piece produced is not a copy but considered an original since it is not a reproduction of another work of art and is technically (more correctly) known as an 'impression'. Printmaking (other than monotyping) is not chosen only for its ability to produce multiple copies, but rather for the unique qualities that each of the printmaking processes lends itself to.

Prints are created from a single original surface, known technically as a matrix. Common types of matrices include: plates of metal, usually copper or zinc for engraving or etching; stone, used for lithography; blocks of wood for woodcuts, linoleum for linocuts and fabric plates for screen-printing. But there are many other kinds of matrix substrates and related processes discussed below.

Works printed from a single plate create an edition, in modern times usually each signed and numbered to form a limited edition. Prints may also be published in book form, as artist's books. A single print could be the product of one or multiple techniques.

Contents |

Techniques

Overview

Printmaking techniques can be divided into the following basic families or categories:

- relief printing, where the ink goes on the original surface of the matrix. Relief techniques include: woodcut or woodblock as the Asian forms are usually known, wood engraving, linocut and metalcut;

- intaglio, where the ink goes beneath the original surface of the matrix. Intaglio techniques include: engraving, etching, mezzotint, aquatint, chine-collé and drypoint;

- planographic, where the matrix retains its entire surface, but some parts are treated to make the image. Planographic techniques include: lithography, monotyping, and digital techniques.

- stencil, including: screen-printing and pochoir

- Viscosity printing

Other types of printmaking techniques outside these groups include collography and foil imaging. Collography is a technique used in printmaking where any textured found material is adhered to the printing plate. This texture is captured on the paper after the print is created. Modern printing technology may be included such as Digital printers, photographic mediums and combination of both digital process and conventional processes.

Many of these techniques can also be combined, especially within the same family. For example Rembrandt's prints are usually referred to as "etchings" for convenience, but very often include work in engraving and drypoint as well, and sometimes have no etching at all.

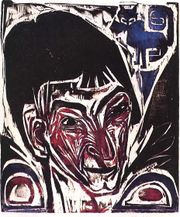

Woodcut

Albrecht Dürer, Werner Drewes, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Dulah Marie Evans, Hiroshige, Hokusai, Gustave Baumann, Hannah Tompkins, Hussein El Gebaly

Woodcut, a type of relief print, is the earliest printmaking technique, and the only one traditionally used in the Far East. It was probably first developed as a means of printing patterns on cloth, and by the 5th century was used in China for printing text and images on paper. Woodcuts of images on paper developed around 1400 in Europe, and slightly later in Japan. These are the two areas where woodcut has been most extensively used purely as a process for making images without text.

The artist draws a sketch either on a plank of wood, or on paper which is transferred to the wood. Traditionally the artist then handed the work to a specialist cutter, who then uses sharp tools to carve away the parts of the block that he/she does not want to receive the ink. The raised parts of the block are inked with a brayer, then a sheet of paper, perhaps slightly damp, is placed over the block. The block is then rubbed with a baren or spoon, or is run through a press. If in color, separate blocks can be used for each color,or a technique called reduction printing can be used.

Reduction printing is a name used to describe the process of using one block to print several layers of color on one print. This usually involves cutting a small amount of the block away, and then printing the block many times over on different sheets before washing the block, cutting more away and printing the next color on top. This allows the previous color to show through. This process can be repeated many times over. The advantages of this process is that only one block is needed, and that different components of an intricate design will line up perfectly. The disadvantage is that once the artist moves on to the next layer, no more prints can be made.

Another variation of woodcut printmaking is the cukil technique, made famous by the Taring Padi underground community in Java, Indonesia. Taring Padi Posters usually resemble intricately printed cartoon posters embedded with political messages. Images--usually resembling a visually complex scenario--are carved unto a wooden surface called cukilan, then smothered with printer's ink before pressing it unto media such as paper or canvas.

Engraving

.jpg)

The process was developed in Germany in the 1430s from the engraving used by goldsmiths to decorate metalwork. Engravers use a hardened steel tool called a burin to cut the design into the surface of a metal plate, traditionally made of copper. Engraving using a burin is generally a difficult skill to learn.

Gravers come in a variety of shapes and sizes that yield different line types. The burin produces a unique and recognizable quality of line that is characterized by its steady, deliberate appearance and clean edges. Other tools such as mezzotint rockers, roulets and burnishers are used for texturing effects.

To make a print, the engraved plate is inked all over, then the ink is wiped off the surface, leaving only ink in the engraved lines. The plate is then put through a high-pressure printing press together with a sheet of paper (often moistened to soften it). The paper picks up the ink from the engraved lines, making a print. The process can be repeated many times; typically several hundred impressions (copies) could be printed before the printing plate shows much sign of wear, except when drypoint, which gives much shallower lines, is used.

In the 20th century, true engraving was revived as a serious art form by artists including Stanley William Hayter.

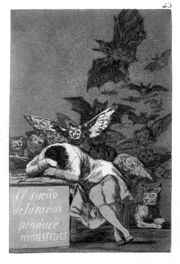

Etching

Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, Francisco Goya, Whistler, Otto Dix, James Ensor, Edward Hopper, Käthe Kollwitz, Pablo Picasso, Cy Twombly, Lucas van Leyden.

Etching is part of the intaglio family (along with engraving, drypoint, mezzotint, and aquatint.) The process is believed to have been invented by Daniel Hopfer (circa 1470-1536) of Augsburg, Germany, who decorated armour in this way, and applied the method to printmaking. Etching soon came to challenge engraving as the most popular printmaking medium. Its great advantage was that, unlike engraving which requires special skill in metalworking, etching is relatively easy to learn for an artist trained in drawing.

Etching prints are generally linear and often contain fine detail and contours. Lines can vary from smooth to sketchy. An etching is opposite of a woodcut in that the raised portions of an etching remain blank while the crevices hold ink. In pure etching, a metal (usually copper, zinc or steel) plate is covered with a waxy or acrylic ground. The artist then draws through the ground with a pointed etching needle. The exposed metal lines are then etched by dipping the plate in a bath of etchant (e.g. nitric acid or ferric chloride). The etchant "bites" into the exposed metal, leaving behind lines in the plate. The remaining ground is then cleaned off the plate, and the printing process is then just the same as for engraving.

Mezzotint

An intaglio variant of engraving where the plate first is roughened evenly all over; the image is then brought out by scraping smooth the surface, creating the image by working from dark to light. It is possible to create the image by only roughening the plate selectively, so working from light to dark.

Mezzotint is known for the luxurious quality of its tones: first, because an evenly, finely roughened surface holds a lot of ink, allowing deep solid colors to be printed; secondly because the process of smoothing the texture with burin, burnisher and scraper allows fine gradations in tone to be developed.

The mezzotint printmaking method was invented by Ludwig von Siegen (1609-1680). The process was especially widely used in England from the mid-eighteenth century, to reproduce portraits and other paintings.

Aquatint

A technique used in Intaglio etchings. Like etching, aquatint technique involves the application of acid to make marks in a metal plate. Where the etching technique uses a needle to make lines that retain ink, aquatint relies on powdered rosin which is acid resistant in the ground to create a tonal effect. The rosin is applied in a light dusting by a fan booth, the rosin is then cooked until set on the plate. At this time the rosin can be burnished or scratched out to affect its tonal qualities. The tonal variation is controlled by the level of acid exposure over large areas, and thus the image is shaped by large sections at a time.

Goya used aquatint for most of his prints.

Drypoint

A variant of engraving, done with a sharp point, rather than a v-shaped burin. While engraved lines are very smooth and hard-edged, drypoint scratching leaves a rough burr at the edges of each line. This burr gives drypoint prints a characteristically soft, and sometimes blurry, line quality. Because the pressure of printing quickly destroys the burr, drypoint is useful only for very small editions; as few as ten or twenty impressions. To counter this, and allow for longer print runs, electro-plating (here called steelfacing) has been used since the nineteenth century to harden the surface of a plate.

The technique appears to have been invented by the Housebook Master, a south German fifteenth century artist, all of whose prints are in drypoint only. Among the most famous artists of the old master print: Albrecht Dürer produced 3 drypoints before abandoning the technique; Rembrandt used it frequently, but usually in conjunction with etching and engraving.

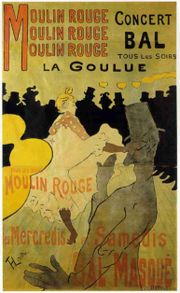

Lithography

Honoré Daumier, George Bellows, Pierre Bonnard, Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, Pablo Picasso, Odilon Redon, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Salvador Dalí, M. C. Escher, Willem de Kooning, Joan Miró, Stow Wengenroth

Lithography is a technique invented in 1798 by Alois Senefelder and based on the chemical repulsion of oil and water. A porous surface, normally limestone, is used; the image is drawn on the limestone with a greasy medium. Acid is applied, transferring the grease to the limestone, leaving the image 'burned' into the surface. Gum arabic, a water soluble substance, is then applied, sealing the surface of the stone not covered with the drawing medium. The stone is wetted, with water staying only on the surface not covered in grease-based residue of the drawing; the stone is then 'rolled up', meaning oil ink is applied with a roller covering the entire surface; since water repels the oil in the ink, the ink adheres only to the greasy parts, perfectly inking the image. A sheet of dry paper is placed on the surface, and the image is transferred to the paper by the pressure of the printing press. Lithography is known for its ability to capture fine gradations in shading and very small detail.

A variant is photo-lithography, in which the image is captured by photographic processes on metal plates; printing is carried out in the same way.

Screen-printing

Josef Albers, Chuck Close, Ralston Crawford, Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, Julian Opie, Robert Rauschenberg, Bridget Riley, Edward Ruscha, and Andy Warhol.

Screen-printing (also known as "screenprinting", "silk-screening", or "serigraphy") creates prints exhibiting a stenciled, complex deposit of ink through the utilization of a fabric stencil technique. Printmakers generally place it in the "planographic" category of printing due to the fact that no impression is actually made- the ink is simply pushed through the stencil against the surface of the paper, rather than kissing off of a surface being pushed into the paper. The general technique is accepted as involving one of many various types of 'mesh' stretched across a rectangular 'frame'- this looks much like a stretched canvas. The mesh can be made of many different types of material, from actual silk, to nylon monofilament and multifilament polyester, to even stainless steel ([1]). While commercial screen printing often involves high-tech, mechanical apparatuses and calibrated materials, printmakers often seem to prize it for the Do It Yourself quality of production and the low technical requirement, high quality results. The essential tools required are a squeegee, a mesh, a frame, a stencil, and a substrate- unlike many other printmaking processes, presses need not be involved on the most basic scale, as screen printing is essentially stencil printing. Stencil printing is arguably the oldest and simplest form of graphic arts. Screen-printing lends itself well to printing on a variety of materials, from canvas to rubber to glass and metal. Artists have used it to print on an incredibly varied type of substrates, from works on bottles to large pieces of granite, directly onto walls, and to make images on objects like textiles which would distort under pressure from printing presses.

Digital prints

Istvan Horkay, Ralph Goings, Enrique Chagoya

Digital prints refers to editions of images printed using a digital printer instead of a traditional printing press. These images can be printed to a variety of substrates including paper and cloth or plastic canvas. Accurate color reproduction and the type of ink used (see below) are key to distinguishing high quality from low quality digital prints. Metallics (silvers, golds) are particularly difficult to reproduce accurately because they reflect light back to digital scanners. High quality digital prints typically are reproduced with very high-resolution data files with very high-precision printers. The substrate used has an effect on the final colors and cannot be ignored when selecting a color palette.

Pigment-based vs. Dye-based inks

Unlike pigment, dyes dissolve when mixed into a liquid. Dyes are organic (not mineral). Although most are synthetic, derived from petroleum, they can be made from vegetable or animal sources. Dyes are well suited for textiles where the liquid dye penetrates and chemically bonds to the fiber. Because of the deep penetration, more layers of material must lose their color before the fading is apparent. Dyes, however, are not suitable for the relatively thin layers of ink laid out on the surface of a print.

Pigment is a finely ground, particulate substance which, when mixed or ground into a liquid to make ink or paint, does not dissolve, but remains dispersed or suspended in the liquid. Pigments are categorized as either inorganic (mineral) or organic (synthetic).[1]

A pigment, such as red iron oxide (rust) is simply an oxidized form of iron. One could leave iron, lead, or gold in the sun for a million years and they would never change color or change into another substance. In contrast, man-made synthetic and vegetable water-soluble dyes can fade rapidly, often within one to six months.

"Giclée" prints

The term Giclée, a made up marketing word from the French "to spurt", is sometimes used in the fine art print community to describe the ink-jet printing processes listed above. It was originally associated with Iris printing process. Today fine art prints produced on inkjet machines using the CcMmYK color model are generally called "Giclée".

Foil imaging

In art, foil imaging is a printmaking technique made using the Iowa Foil Printer, developed by Virginia A. Myers from the commercial foil stamping process. This uses gold leaf and acrylic foil in the printmaking process.

Color

Printmakers apply color to their prints in many different ways. Often color in printmaking that involves etching, screenprinting, woodcut, or linocut is applied by either using separate plates, blocks or screens or by using a reductionist approach. In multiple plate color techniques, a number of plates, screens or blocks are produced, each providing a different color. Each separate plate, screen, or block will be inked up in a different color and applied in a particular sequence to produce the entire picture. On average about 3 to 4 plates are produced, but there are occasions where a printmaker may use up to seven plates. Every application of another plate of color will interact with the color already applied to the paper, and this must be kept in mind when producing the separation of colors. The lightest colors are often applied first, and then darker colors successively until the darkest.

The reductionist approach to producing color is to start with a lino or wood block that is either blank or with a simple etching. Upon each printing of color the printmaker will then further cut into the lino or woodblock removing more material and then apply another color and reprint. Each successive removal of lino or wood from the block will expose the already printed color to the viewer of the print. Picasso is often cited as the inventor of reduction printmaking, although there is evidence of this method in use 25 years before Picasso's linocuts.[2]

With some printing techniques like chine-collé or monotyping the printmaker may sometimes just paint into the colors they want like a painter would and then print.

The subtractive color concept is also used in offset or digital print and is present in bitmap or vectorial software in CMYK or other color spaces.

Registration

In printmaking processes requiring more than one application of ink or other medium, the problem exists as to how to line up properly areas of an image to receive ink in each application. The most obvious example of this would be a multi-color image in which each color is applied in a separate step. The lining up of the results of each step in a multistep printmaking process is called "registration." Proper registration results in the various components of an image being in their proper place. But, for artistic reasons, improper registration is not necessarily the ruination of an image.

This can vary considerably from process to process. It generally involves placing the substrate, generally paper, in correct alignment with the printmaking element that will be supplying it with coloration.[3]

Protective printmaking equipment

Protective clothing is very important for printmakers who engage in etching and lithography (closed toed shoes and long pants). In the past, many printmakers did not live far past 35 to 40 years of age because of their exposure to various acids, solvents, particles, and vapors inherent in the printmaking process.

Whereas in the past printmakers put their plates in and out of acid baths with their bare hands, today printmakers use rubber gloves. They also wear industrial respirators for protection from caustic vapors. Most acid baths are built with ventilation hoods above them.

Often, an emergency cold shower or eye wash station is nearby in case of acid spillages, as well as soda ash- which neutralizes most acids. Some printmakers wear goggles when dealing with acid.

Protective respirators and masks should have particle filters, particularly for aquatinting. As a part of the aquatinting process, a printmaker is often exposed to rosin powder. Rosin is a serious health hazard, especially to printmakers who, in the past, simply used to hold their breath using an aquatinting booth.

Barrier cream is often used upon a printmaker's hands both when putting them inside the protective gloves and if using their hands to wipe plates (wipe ink into the grooves of the plate and remove excess).

Sterile plasters and bandages should always be available to treat cuts and scrapes. For example, zinc plates can be extremely sharp when their edges are not beveled.

Gallery

Felix Vallotton, La raison probante (The Cogent Reason), woodcut from the series Intimités, 1898 |

||

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-portrait, etching, c.1630 |

Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Preaching, (The Hundred Guilder print); etching c.1648 |

.jpg) Francisco Goya, There is No One To Help Them, Disasters of War series, aquatint c.1810 |

Contemporary Printmaking. Catalogue of the 29 Mini Print International of Cadaques. 2009

See also

- Artist's proof

- Banhua, Chinese printmaking

- Carborundum printmaking

- Edition

- Graphic design

- Iowa Biennial Exhibition & Archive of Contemporary Prints

- Line engraving

- Old master print

- Shin hanga

- Sosaku hanga

- Ukiyo-e

- Viscosity printing

- List of Printmakers

Printmakers by nationality

- Engravers by nationality

- Etchers by nationality

- Printmakers by nationality

Notes

References

- What is a Print?, from the Museum of Modern Art

- Bamber Gascoigne: How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet (ISBN 0-500-28480-6)

- Multi-Color Block Prints: Wood/Linoleum - Reduction Method Technique, by Hannah Tompkins

Further reading

- Grabowski, Beth and Fick, Bill, "Printmaking: A Complete Guide to Materials & Processes." Prentice Hall, 2009. ISBN 0205664539

- Anderson, Donna, Experience Printmaking. Worcester, MA: Davis Publications, 2009. ISBN 9780871929822

- Gill Saunders and Rosie Miles Prints Now: Directions and Definitions Victoria and Albert Museum (May 1, 2006) ISBN 1-85177-480-7

- Griffiths, Antony, Prints and Printmaking, British Museum Press, 2nd ed, 1996 ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- Hults, Linda The Print in the Western World: An Introductory History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-299-13700-7

- Ivins, William Jr. Prints and Visual Communication. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1953. ISBN 0-262-59002-6

- Watrous, James A Century of American Printmaking. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984. ISBN 0-299-09680-7

External links

History, glossaries

- Museum of Modern Art, New York: What Is a Print?

- Thompson, Wendy. "The Printed Image in the West: History and Techniques". In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 – . (October 2003)

- André Béguin's dictionary;enormous dictionary of terms, relating more to the printing than the creation of the image

- Another glossary - for modern prints

- Large list of links to museum etc. online images of prints

- Bill Fisher's Links

- Judging the Authenticity of Prints by The Masters by art historian David Rudd Cycleback

Organizations, etc.

- SGC International (formerly Southern Graphics Council)

- Seattle Print Arts

- Bellebyrd - The Print Australia blogspot by art historian Josephine Severn.

- Iowa Biennial - Exhibition & Archive of Contemporary Prints

- Site dedicated to the activity of printmaking and thinking creatively. Includes footage of well-known artists working at Crown Point Press in San Francisco.

- Prints and Printmaking: Site devoted to Australian and Pacific printmaking practice and history

- Mini Print International of Cadaques Site of the longest running international print exhibition and competition, catalogues, archive, winners, exhibitions, jury...

|

|||||