Quinoa

| Quinoa | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Core eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Amaranthaceae |

| Subfamily: | Chenopodioideae |

| Genus: | Chenopodium |

| Species: | C. quinoa |

| Binomial name | |

| Chenopodium quinoa Willd. |

|

- For the town with a similar name, see Quinua, Peru. Quinoa is also a title of a 1992 music album by Tangerine Dream.

Quinoa (pronounced /ˈkiːnoʊ.ə/ or /kwɨˈnoʊ.ə/, Spanish quinua, from Quechua kinwa), a species of goosefoot (Chenopodium), is a grain-like crop grown primarily for its edible seeds. It is a pseudocereal rather than a true cereal, or grain, as it is not a member of the grass family. As a chenopod, quinoa is closely related to species such as beets, spinach, and tumbleweeds. Its leaves are also eaten as a leaf vegetable, much like amaranth, but the commercial availability of quinoa greens is currently limited.

Contents |

Overview

Quinoa originated in the Andean region of South America,[1] where it has been an important food for 6,000 years. Its name is the Spanish spelling of the Quechua name. Quinoa is generally undemanding and altitude-hardy, so it can be easily cultivated in the Andes up to about 4,000 meters. Even so, it grows best in well-drained soils and requires a relatively long growing season. In eastern North America, it is susceptible to a leaf miner that may reduce crop success; this leaf miner also affects the common weed and close relative Chenopodium album, but C. album is much more resistant.

Similar Chenopodium species, such as pitseed goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri) and fat hen (Chenopodium album), were grown and domesticated in North America as part of the Eastern Agricultural Complex before maize agriculture became popular. Fat hen, which has a widespread distribution in the Northern Hemisphere, produces edible seeds and greens much like quinoa, but in lower quantities.

Quinoa greens |

Quinoa before flowering |

Quinoa in flower |

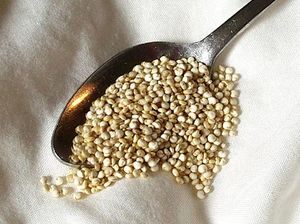

Harvested quinoa seeds |

Wild distribution

Chenopodium quinoa (and a related species from Mexico, Chenopodium nuttalliae) is most familiar as a fully domesticated plant, but it was believed to have been domesticated in the Andes from wild populations of Chenopodium quinoa.[2] There are non-cultivated quinoa plants (Chenopodium quinoa var. melanospermum) which grow in the same area where it is cultivated; those are probably related to quinoa's wild predecessors, but could instead be descendants of cultivated plants.[3]

History and culture

| World Quinoa Production - 2005 (thousand metric ton) |

|

|---|---|

| 32.6 | |

| 25.2 | |

| 0.7 | |

| World Total | 58.4 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) Current figures from FAO |

|

The Incas, who held the crop to be sacred,[4] referred to quinoa as chisaya mama or mother of all grains, and it was the Inca emperor who would traditionally sow the first seeds of the season using 'golden implements'.[4] During the European conquest of South America quinoa was scorned by the Spanish colonists as food for Indians, and even actively suppressed, due to its status within indigenous non-Christian ceremonies. In fact, the conquistadors forbade quinoa cultivation for a time and the Incas were forced to grow corn instead.

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,539 kJ (368 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 64 g |

| Starch | 52 g |

| Dietary fibre | 7 g |

| Fat | 6 g |

| polyunsaturated | 3.3 g |

| Protein | 14 g |

| Water | 13 g |

| Thiamine (Vit. B1) | 0.36 mg (28%) |

| Riboflavin (Vit. B2) | 0.32 mg (21%) |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.5 mg (38%) |

| Folate (Vit. B9) | 184 μg (46%) |

| Vitamin E | 2.4 mg (16%) |

| Iron | 4.6 mg (37%) |

| Magnesium | 197 mg (53%) |

| Phosphorus | 457 mg (65%) |

| Zinc | 3.1 mg (31%) |

| Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient database |

|

Quinoa was of great nutritional importance in pre-Columbian Andean civilizations, being secondary only to the potato, and was followed in importance by maize. In contemporary times, this crop has become highly appreciated for its nutritional value, as its protein content is very high (12%–18%). Unlike wheat or rice (which are low in lysine), and like oats, quinoa contains a balanced set of essential amino acids for humans, making it an unusually complete protein source among plant foods.[5] It is a good source of dietary fiber and phosphorus and is high in magnesium and iron. Quinoa is gluten-free and considered easy to digest. Because of all these characteristics, quinoa is being considered a possible crop in NASA's Controlled Ecological Life Support System for long-duration manned spaceflights.[5]

Saponin content

Quinoa in its natural state has a coating of bitter-tasting saponins, making it unpalatable. Most quinoa sold commercially in North America has been processed to remove this coating.[1] Some have speculated this bitter coating may have caused the Europeans who first encountered quinoa to reject it as a food source, since they adopted other indigenous food plants of the Americas like maize and potatoes. This bitterness has beneficial effects during cultivation, as the plant is unpopular with birds and thus requires minimal protection. There have been attempts to lower the saponin content of quinoa through selective breeding to produce sweeter, more palatable varieties. However, when new varieties were developed by agronomists, native growers in the high plateau rejected the new varieties despite their high projected yields; because the seeds no longer had a bitter coating, birds had consumed the entire crop after just one season.

The saponins in quinoa can be mildly toxic, as can be the oxalic acid in the leaves of all the Chenopodium family. Reports of numbness of the lips and tongue have been reported after eating cooked but unwashed quinoa. The risks associated with quinoa are minimal, provided it is properly prepared and leaves are not eaten to excess.

Preparation

Quinoa has a light, fluffy texture when cooked, and its mild, slightly nutty flavor makes it an alternative to white rice or couscous.

The first step in preparing quinoa is to remove the saponins, a process that requires soaking the grain in water for a few hours, then changing the water and resoaking, or rinsing it in ample running water either in a fine strainer or in cheesecloth. Removal of the saponin helps with digestion; the soapy nature of the compound makes it act as a laxative. Most boxed quinoa has been pre-rinsed for convenience.

A common cooking method is to treat quinoa much like rice, bringing two cups of water to a boil with one cup of grain, covering at a low simmer and cooking for 14–18 minutes or until the germ separates from the seed. The cooked germ looks like a tiny curl and should have a slight bite to it (like al dente pasta). As an alternative, one can use a rice cooker to prepare quinoa, treating it just like white rice (for both cooking cycle and water amounts).

Vegetables and seasonings can also be added to make a wide range of dishes. Chicken or vegetable stock can be substituted for water during cooking, adding flavor. It is also suited to vegetable pilafs, complementing bitter greens like kale.

Quinoa can serve as a high-protein breakfast food mixed with honey, almonds, or berries; it is also sold as a dry product, much like corn flakes. Quinoa flour can be used in wheat-based and gluten-free baking.

Quinoa may be germinated in its raw form to boost its nutritional value. Germination activates its natural enzymes and multiplies its vitamin content.[6] In fact, quinoa has a notably short germination period: Only 2–4 hours resting in a glass of clean water is enough to make it sprout and release gases, as opposed to, e.g., 12 hours overnight with wheat. This process, besides its nutritional enhancements, softens the grains, making them suitable to be added to salads and other cold foods.

Name

This crop is known as quinoa in English and, according to Merriam-Webster, the primary pronunciation is with two syllables with the accent on the first (English pronunciation: /ˈkiːnwɑː/) (KEEN-wah).[7] It may also be pronounced with three syllables, with the stress on either the first syllable (/ˈkiːnoʊ.ə/ KEE-noe-ə) or on the second (/kwɨˈnoʊ.ə/ kwi-NOE-ə). In Spanish, the spelling and pronunciation vary by region. The accent may be on the first syllable, in which case it is usually spelled quinua [ˈkinwa], with quínoa [ˈkinoa] being a variant; or on the second syllable: [kiˈnoa]), in which case it is spelled quinoa. The name derives from the Quechua kinwa, pronounced in the standard dialect [ˈkinwa]. There are multiple other native names in South America:

- Quechua: ayara, kiuna, kuchikinwa, achita, kinua, kinoa, chisaya mama

- Aymara: supha, jopa, jupha, juira, ära, qallapi, vocali

- Chibchan: Suba, pasca

- Mapudungun: dawe, sawe

See also

- Deficit irrigation

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Quinoa". Alternative Field Crops Manual. University of Wisconsin Extension and University of Minnesota. January 20, 2000. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/NEWCROP/AFCM/quinoa.html.

- ↑ Barbara Pickersgill (August 31, 2007). "Domestication of Plants in the Americas: Insights from Mendelian and Molecular Genetics". Annals of Botany 100 (5): 925. doi:10.1093/aob/mcm193. PMID 17766847. PMC 2759216. http://aob.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/mcm193v1.

- ↑ Charles B. Heiser Jr. and David C. Nelson (September 1974). "On the origin of the cultivated chenopods (Chenopodium)". Genetics 78 (1): 503–5. doi:10.1093/aob/mcm193. PMID 4442716. PMC 1213209. http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/abstract/78/1/503.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Popenoe, Hugh (1989). Lost crops of the Incas: little-known plants of the Andes with promise for worldwide cultivation. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-309-04264-X. http://books.google.com/books?id=jMlxpytjZq0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Lost+crops+of+the+Incas&hl=en&ei=QJ97TN6cC8fKjAeexKyfDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=quinoa&f=false.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Greg Schlick and David L. Bubenheim (November 1993). "Quinoa: An Emerging "New" Crop with Potential for CELSS (NASA Technical Paper 3422)" (PDF). http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19940015664_1994015664.pdf.

- ↑ Deep Nutrition: Why Your Genes Need Traditional Foods, Catherine Shanahan, MD, Luke Shanahan (2008) pp148-151

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary, quinoa

External links

- Quinoa at the Open Directory Project

- Geerts S, Raes D (2009). "Deficit irrigation as an on-farm strategy to maximize crop water productivity in dry areas". Agric. Water Manage 96: 1275–84. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2009.04.009.

- Geerts S, Raes D, Garcia M, Vacher J, Mamani R, Mendoza J, Huanca R, Morales B, Miranda R, Cusicanqui J, Taboada C (2008). "Introducing deficit irrigation to stabilize yields of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.)". Eur. J. Agron. 28: 427–436. doi:10.1016/j.eja.2007.11.008.

- Geerts S, Raes D, Garcia M, Mendoza J, Huanca R (2008). "Indicators to quantify the flexible phenology of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) in response to drought stress". Field Crop. Res. 108: 150–6. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2008.04.008.

- Geerts S, Raes D, Garcia M, Condori O, Mamani J, Miranda R, Cusicanqui J, Taboada C, Vacher J (2008). "Could deficit irrigation be a sustainable practice for quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) in the Southern Bolivian Altiplano?". Agric. Water Manage 95: 909–917. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2008.02.012.

- Geerts S, Raes D, Garcia M, Taboada C, Miranda R, Cusicanqui J, Mhizha T, Vacher J (2009). "Modeling the potential for closing quinoa yield gaps under varying water availability in the Bolivian Altiplano.". Agric. Water Manage 96: 1652–1658. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2009.06.020.

- Geerts S, Raes D, Garcia M, Miranda R, Cusicanqui J, Taboada C, Mendoza J, Huanca R, Mamani A, Condori O, Mamani J, Morales B, Osco V, Steduto P (2009). "Simulating Yield Response of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) to Water Availability with AquaCrop.". Agron. J. 101: 499–508. doi:10.2134/agronj2008.0137s.

- AquaCrop: the new crop water productivity model from FAO

|

|||||