STS-1

| STS-1 |

Mission insignia

|

| Mission statistics |

| Mission name |

STS-1 |

| Space shuttle |

Columbia |

| Crew size |

2 |

| Launch pad |

Kennedy Space Center, Florida

LC 39A |

| Launch date |

12 April 1981 12:00:03 (1981-04-12T12:00:03) UTC |

| Landing site |

Edwards AFB, Runway 23 |

| Landing |

14 April 1981 18:20:57 (1981-04-14T18:20:58) UTC |

| Mission duration |

2d/6:20:53 |

| Number of orbits |

37 |

| Apogee |

156 mi (251 km) |

| Perigee |

149 mi (240 km) |

| Orbital period |

89.4 min |

| Orbital altitude |

307 km (191 mi) |

| Orbital inclination |

40.3 degrees |

| Distance traveled |

172,800,000 kilometres (107,400,000 mi) |

| Crew photo |

|

| Crew members John W. Young (left) and Robert L. Crippen pose in ejection escape suits (EES) with small model of the space shuttle orbiter. |

| Related missions |

| Previous mission |

Subsequent mission |

Approach and Landing Tests Approach and Landing Tests |

STS-2 STS-2 |

|

STS-1 was the first orbital flight of the United States Space Shuttle, launched on 12 April 1981, and returning to Earth 14 April. Space Shuttle Columbia orbited the earth 37 times in this 54.5-hour mission. It was the first US manned space flight since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project on 15 July 1975. STS-1 was the only US manned maiden test flight of a new spacecraft system, although it was the culmination of atmospheric testing of the Space Shuttle orbiter.

Crew

| Position |

Astronaut |

| Commander |

John W. Young

Fifth spaceflight |

| Pilot |

Robert Crippen

First spaceflight |

Backup crew

| Position |

Astronaut |

| Commander |

Joe Engle |

| Pilot |

Richard Truly |

Mission parameters

- Mass:

- Orbiter Liftoff: 219,256 lb (99,453 kg)

- Orbiter Landing: 195,466 lb (88,662 kg)

- DFI payload: 10,822 lb (4,909 kg)

- Perigee: 149 mi (240 km)

- Apogee: 156 mi (251 km)

- Inclination: 40.3°

- Period: 89.4 min

Mission highlights

The first launch of the Space Shuttle occurred on 12 April 1981, exactly 20 years after the first manned space flight, when the orbiter Columbia, with two crew members, astronauts John W. Young, commander, and Robert L. Crippen, pilot, lifted off from Pad A, Launch Complex 39, at the Kennedy Space Center — the first of 24 launches from Pad A. It was exactly 7 a.m. EST. A launch attempt 2 days earlier was scrubbed because of a timing problem in one of Columbia’s general purpose computers.

Not only was this the first launch of the Space Shuttle, but it marked the first time that solid-fuel rockets were used for a U.S. manned launch. (Note that all Mercury and Apollo astronauts had relied on a solid-fuel motor in the escape tower.) It was also the first U.S. manned space vehicle launched without an unmanned powered test flight. The STS-1 orbiter, Columbia, also holds the record for the amount of time spent in the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) before launch — 610 days, time needed for replacement of many of its heat shield tiles.

Primary mission objectives of the maiden flight were to check out the overall Shuttle system, accomplish a safe ascent into orbit and to return to Earth for a safe landing. The only payload carried on the mission was a Development Flight Instrumentation (DFI) package which contained sensors and measuring devices to record orbiter performance and the stresses that occurred during launch, ascent, orbital flight, descent and landing. All of these objectives were met successfully, and the Shuttle's worthiness as a space vehicle was verified.

The STS-1 Shuttle reached an orbital altitude of 166 nautical miles. The 37-orbit, 1,074,567-mile-long flight lasted 2 days, 6 hours, 20 minutes and 53 seconds. Landing occurred on Runway 23 at Edwards Air Force Base, California at 10:21 a.m. PST, 14 April 1981.[1] Columbia was returned to Kennedy Space Center from California on April 28 atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft.

Mission anomalies

STS-1 was the first test flight of what was, at the time, probably the most complex spacecraft ever built. There were numerous problems – 'anomalies' in NASA parlance – on the flight, as many systems could not be adequately tested on the ground or independently. Some of the more serious or interesting were:

- According to Space.com[2], STS-1 was the only Shuttle to launch after T-0. Video of the launch corroborates this.[3]

- A tile next to the right-hand External Tank (ET) door on the underside of the shuttle was incorrectly installed, leading to excessive re-entry heating and melting of part of the ET door latch.

- Inspection by astronauts while in orbit showed significant damage to the thermal protection tiles on the OMS/RCS pods at the orbiter aft end, and John Young reported that two tiles on the nose looked like someone had taken 'big bites out of them'.[4] Post-flight inspection of Columbia's heat shield revealed that an overpressure wave from the Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) ignition resulted in the loss of 16 tiles and damage to 148 others.

- The same overpressure wave pushed the body flap below the main engines at the rear of the shuttle well past the point where damage to the hydraulic system would be expected, which would have made a safe re-entry impossible. The crew were unaware of this until after the flight, and John Young reportedly said that if they had been aware of the potential damage at the time, they would have flown the shuttle up to a safe altitude and ejected, causing Columbia to have been lost on the first flight.[5]

- Bob Crippen reported that all through the first stage of the launch up to SRB separation, he saw 'white stuff' coming off the External Tank and splattering the windows, which was probably the white paint covering the ET thermal foam.[4]

- The toilet suffered from 'low urinal flow and a feces separation problem'.[6]

- Columbia's aerodynamics at high Mach number were found to differ significantly in some respects from those estimated in pre-flight testing. A misprediction of the location of the center of pressure (due to using an ideal gas model instead of a real gas model) caused the computer to extend the body flap by sixteen degrees rather than the expected eight or nine, and side-slip during the first bank reversal maneuver was twice as high as predicted.[7]

- During remarks at a 2003 gathering, John Young stated that a protruding tile gap filler ducted hot gas into the right main landing gear well, which caused significant damage including buckling of the landing gear[8]. Buckling of the door, but not the landing gear, is documented in the post-flight anomaly report[9].

Despite these problems, STS-1 was a successful test, and in most respects Columbia came through with flying colors. After some modifications to the shuttle and to the launch and re-entry procedures, Columbia would fly the next four Shuttle missions.

Mission insignia

The artwork for the official mission insignia was designed by artist Robert McCall. It is a symbolic representation of the shuttle. The image does not depict the black wing roots present on the actual shuttle.

Anniversary

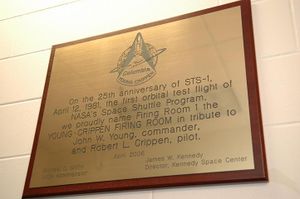

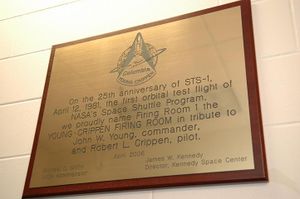

The plaque of the Young-Crippen Firing Room in the Launch Control Center at Kennedy Space Center

The ultimate launch date of STS-1 fell on the 20th anniversary of Vostok 1, the first manned spaceflight. Yuri's Night is an international celebration held on April 12 every year to commemorate the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, as well as the first Space Shuttle launch.

In tribute to the 25th anniversary of the first flight of Space Shuttle, Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control Center at Kennedy Space Center was renamed to the Young-Crippen Firing Room, dedicating the firing room that launched the historic flight and the crew of STS-1.

NASA described the mission as: "The boldest test flight in history".[10]

External tank

STS-1 was one of only two shuttle flights to have its External Tank (ET) painted white. In an effort to reduce the Shuttle's overall weight, all flights from STS-3 onward used an unpainted tank. The use of an unpainted tank provides a weight savings of approximately 272 kilograms (600 lb),[11] and gives the ET the distinctive orange color which is now associated with the Space Shuttle.

Cultural references

The song "Countdown", by Rush, from the 1982 album Signals, was written about STS-1 and the inaugural flight of Columbia.[12] The song was "dedicated with thanks to astronauts Young and Crippen and all the people of NASA for their inspiration and cooperation".

Hail Columbia!

IMAX cameras filmed the launch, landing, and mission control during the flight, for a film entitled Hail Columbia!, which debuted in 1982 and is now available on DVD. The title of the film comes from the pre-1930s unofficial American national anthem, also titled Hail, Columbia.

Wake-up calls

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, which was first used to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15.[13] This special musical track at the start of each day in space was chosen, sometimes by their families, to have a special meaning to an individual member of the crew or to the day's planned activities.[14]

| Flight Day |

Song |

Artist/Composer |

Day 2

|

"Blast-Off Columbia" |

Roy McCall |

Day 3

|

"Reveille" |

Houston DJs Hudson and Harrigan |

Gallery

See also

- Space science

- Space shuttle thermal protection system

- Space Shuttle program

- List of space shuttle missions

- List of human spaceflights chronologically

References

- ↑ STS-1 Overview

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 STS-1 Technical Crew Debriefing, page 4-4

- ↑ "Cosmic log". MSNBC. April 12, 2006. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12243173/#060412b. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ STS-1 In-Flight Anomaly report, page 22

- ↑ Kenneth Iliff and Mary Shafer, Space Shuttle Hypersonic Aerodynamic and Aerothermodynamic Flight Research and the Comparison to Ground Test Results, Page 5-6

- ↑ Space Review

- ↑ STS-1 In-Flight Anomaly report, page 33

- ↑ http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/sts1/index.html

- ↑ National Aeronautics and Space Administration "NASA Takes Delivery of 100th Space Shuttle External Tank." Press Release 99-193. 16 August 1999.

- ↑ "25 years later, JSC remembers shuttle’s first flight". JSC Features. Johnson Spaceflight Center. issue 502. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/jscfeatures/articles/000000502.html. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ↑ Fries, Colin (June 25, 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/wakeup%20calls.pdf. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ NASA (May 11, 2009). "STS-1 Wakeup Calls". NASA.

External links

|

Space Shuttle Columbia (OV-102) |

|

| Flights |

STS-1 · STS-2 · STS-3 · STS-4 · STS-5 · STS-9 · STS-61-C · STS-28 · STS-32 · STS-35 · STS-40 · STS-50 · STS-52 · STS-55 · STS-58 · STS-62 · STS-65 · STS-73 · STS-75 · STS-78 · STS-80 · STS-83 · STS-94 · STS-87 · STS-90 · STS-93 · STS-109 · STS-107

|

|

| Status |

Out of service: destroyed 1 February 2003 (STS-107) |

|

| See also |

Columbia Accident Investigation Board · STS-144

|

|

|

U.S. Space Shuttle missions |

|

| Completed flights |

STS-1 · STS-2 · STS-3 · STS-4 · STS-5 · STS-6 · STS-7 · STS-8 · STS-9 · STS-41-B · STS-41-C · STS-41-D · STS-41-G · STS-51-A · STS-51-C · STS-51-D · STS-51-B · STS-51-G · STS-51-F · STS-51-I · STS-51-J · STS-61-A · STS-61-B · STS-61-C · STS-51-L · STS-26 · STS-27 · STS-29 · STS-30 · STS-28 · STS-34 · STS-33 · STS-32 · STS-36 · STS-31 · STS-41 · STS-38 · STS-35 · STS-37 · STS-39 · STS-40 · STS-43 · STS-48 · STS-44 · STS-42 · STS-45 · STS-49 · STS-50 · STS-46 · STS-47 · STS-52 · STS-53 · STS-54 · STS-56 · STS-55 · STS-57 · STS-51 · STS-58 · STS-61 · STS-60 · STS-62 · STS-59 · STS-65 · STS-64 · STS-68 · STS-66 · STS-63 · STS-67 · STS-71 · STS-70 · STS-69 · STS-73 · STS-74 · STS-72 · STS-75 · STS-76 · STS-77 · STS-78 · STS-79 · STS-80 · STS-81 · STS-82 · STS-83 · STS-84 · STS-94 · STS-85 · STS-86 · STS-87 · STS-89 · STS-90 · STS-91 · STS-95 · STS-88 · STS-96 · STS-93 · STS-103 · STS-99 · STS-101 · STS-106 · STS-92 · STS-97 · STS-98 · STS-102 · STS-100 · STS-104 · STS-105 · STS-108 · STS-109 · STS-110 · STS-111 · STS-112 · STS-113 · STS-107 · STS-114 · STS-121 · STS-115 · STS-116 · STS-117 · STS-118 · STS-120 · STS-122 · STS-123 · STS-124 · STS-126 · STS-119 · STS-125 · STS-127 · STS-128 · STS-129 · STS-130 · STS-131 · STS-132 |

|

| Upcoming flights |

STS-133 · STS-134 · STS-135

|

|

| Future Launch on Need rescue mission |

STS-3xx

|

|

| Cancelled missions |

STS-41-F · STS-62-A · STS-61-M · STS-61-H · STS-144 · STS-3xx · STS-400

|

|

| Operational orbiters |

|

|

| Orbiters no longer in service |

|

|