Scrotum

| Scrotum | |

|---|---|

| Human scrotum | |

| Gray's | subject #258 1237 |

| Artery | Anterior scrotal artery & Posterior scrotal artery |

| Vein | Testicular vein |

| Nerve | Posterior scrotal nerves, Anterior scrotal nerves, genital branch of genitofemoral nerve, perineal branches of posterior femoral cutaneous nerve |

| Lymph | Superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Precursor | labioscrotal folds |

| MeSH | Scrotum |

In some male mammals the scrotum (also referred to as the cod) is a dual-chambered protuberance of skin and muscle containing the testicles and divided by a septum. It is an extension of the abdomen, and is located between the penis and anus. In humans and some other mammals, the base of the scrotum becomes covered with curly pubic hairs at puberty. The scrotum is homologous to the labia majora in females.

Contents |

Function

The function of the scrotum appears to be to keep the testes at a temperature slightly lower than that of the rest of the body. For human beings, the temperature should be one or two degrees Celsius below body temperature (37 degrees Celsius or 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit); higher temperatures may be damaging to sperm count. The temperature is controlled by the scrotum moving the testicles closer to the abdomen when the ambient temperature is cold, and further away when it is hot. Moving the testes away from the abdomen and increasing the exposed surface area allow a faster dispersion of excess heat. This is done by means of contraction and relaxation of the cremaster muscle in the abdomen and the dartos fascia (muscular tissue under the skin) in the scrotum.

However, this may not be the main function of the scrotum. The volume of sperm produced by the testes is small (0.1-0.2 ml). It has been suggested that if testes were situated within the abdominal cavity that they would be subjected to the regular changes in abdominal pressure that is exerted by the abdominal muscles. This squeezing and relaxing would result in the more rapid emptying of the testes and epididymis of sperm before the spermatozoa were matured sufficiently for fertilization. Some mammals—elephants and marine mammals, for example—do keep their testes within the abdomen and there may be mechanisms to prevent this inadvertent emptying.

Contraction of the abdominal muscles, and changes in intra-abdominal pressure, often can lift and lower the testicles within the scrotum. Contraction of the muscle fibers of the dartos tunic (or fascia) is completely involuntary and results in the appearance of increased wrinkling and thickening of the scrotal skin. The testicles are not directly attached to the skin of the scrotum, so this dartos contraction results in their sliding toward the abdomen. They also, in some men, can be lifted the same way by tightening the anus and pelvic muscles, doing Kegel exercises.

Although the ideal temperature for sperm growth varies between species, it usually appears, in warm-blooded species, to be a bit cooler than internal body temperature, necessitating the scrotum. Since this leaves the testicles vulnerable in many species, there is some debate on the evolutionary advantage of such a system. One theory is that the impregnation of females who are ill is less likely when sperm is highly sensitive to elevated body temperatures. An alternative explanation is to protect the testes from jolts and compressions associated with an active lifestyle. Animals that have 'stately' movements—such as elephants, whales, and marsupial moles—have internal testes and no scrotum.[1]

Health issues

A common problem of the scrotum is the development of masses. Common scrotal masses include

- Sebaceous cyst, also called an epidermal cyst

- hydrocele

- hematocele

- spermatocele

- varicocele

Other conditions include:

- contact dermatitis: may cause redness, burning, swelling, and itching of the entire scrotum. Can result from soaps, solvents, detergents, and natural irritants such as poison ivy.

- inguinal hernia

- yeast infection

- swelling resulting from conditions external to the scrotum, including:

- heart failure

- kidney or liver disease

- Cherry angioma

- testicular torsion

References

Additional images

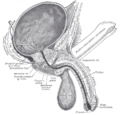

Structure of the male genitalia. |

Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra. |

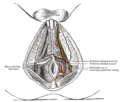

The superficial branches of the internal pudendal artery. |

constricted human scrotum (eplilated), with the raphe clearly exposed |

See also

- Perineal raphe

- Erogenous zone

- Sex organ

- Castration

- Blue balls

- Scrotoplasty

- Scrotum inflation

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||