Sol-gel

The sol-gel process, also known as chemical solution deposition, is a wet-chemical technique widely used in the fields of materials science and ceramic engineering. Such methods are used primarily for the fabrication of materials (typically a metal oxide) starting from a chemical solution which acts as the precursor for an integrated network (or gel) of either discrete particles or network polymers. Typical precursors are metal alkoxides and metal chlorides, which undergo various forms of hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions.

Contents |

Introduction

In this chemical procedure, the 'sol' (or solution) gradually evolves towards the formation of a gel-like diphasic system containing both a liquid phase and solid phase whose morphologies range from discrete particles to continuous polymer networks. In the case of the colloid, the volume fraction of particles (or particle density) may be so low that a significant amount of fluid may need to be removed initially for the gel-like properties to be recognized. This can be accomplished in any number of ways. The simplest method is to allow time for sedimentation to occur, and then pour off the remaining liquid. Centrifugation can also be used to accelerate the process of phase separation.

Removal of the remaining liquid (solvent) phase requires a drying process, which is typically accompanied by a significant amount of shrinkage and densification. The rate at which the solvent can be removed is ultimately determined by the distribution of porosity in the gel. The ultimate microstructure of the final component will clearly be strongly influenced by changes imposed upon the structural template during this phase of processing.

Afterwards, a thermal treatment, or firing process, is often necessary in order to favor further polycondensation and enhance mechanical properties and structural stability via final sintering, densification and grain growth. One of the distinct advantages of using this methodology as opposed to the more traditional processing techniques is that densification is often achieved at a much lower temperature.

The precursor sol can be either deposited on a substrate to form a film (e.g., by dip coating or spin coating), cast into a suitable container with the desired shape (e.g., to obtain monolithic ceramics, glasses, fibers, membranes, aerogels), or used to synthesize powders (e.g., microspheres, nanospheres). The sol-gel approach is a cheap and low-temperature technique that allows for the fine control of the product’s chemical composition. Even small quantities of dopants, such as organic dyes and rare earth elements, can be introduced in the sol and end up uniformly dispersed in the final product. It can be used in ceramics processing and manufacturing as an investment casting material, or as a means of producing very thin films of metal oxides for various purposes. Sol-gel derived materials have diverse applications in optics, electronics, energy, space, (bio)sensors, medicine (e.g., controlled drug release), reactive material and separation (e.g., chromatography) technology.

The interest in sol-gel processing can be traced back in the mid-1880s with the observation that the hydrolysis of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) under acidic conditions led to the formation of SiO2 in the form of fibers and monoliths. Sol-gel research grew to be so important that in the 1990s more than 35,000 papers were published worldwide on the process. [1] [2] [3]

Particles and polymers

The sol-gel process is a wet-chemical technique used for the fabrication of both glassy and ceramic materials. In this process, the sol (or solution) evolves gradually towards the formation of a gel-like network containing both a liquid phase and a solid phase. Typical precursors are metal alkoxides and metal chlorides, which undergo hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions to form a colloid. The basic structure or morphology of the solid phase can range anywhere from discrete colloidal particles to continuous chain-like polymer networks. [4][5]

The term colloid is used primarily to describe a broad range of solid-liquid (and/or liquid-liquid) mixtures, all of which contain distinct solid (and/or liquid) particles which are dispersed to various degrees in a liquid medium. The term is specific to the size of the individual particles, which are larger than atomic dimensions but small enough to exhibit Brownian motion. If the particles are large enough, then their dynamic behavior in any given period of time in suspension would be governed by forces of gravity and sedimentation. But if they are small enough to be colloids, then their irregular motion in suspension can be attributed to the collective bombardment of a myriad of thermally agitated molecules in the liquid suspending medium, as described originally by Albert Einstein in his dissertation. Einstein concluded that this erratic behavior could adequately be described using the theory of Brownian motion, with sedimentation being a possible long term result. This critical size range (or particle diameter) typically ranges from tens of angstroms (10−10 m) to a few micrometres (10−6 m).[6]

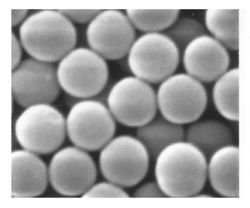

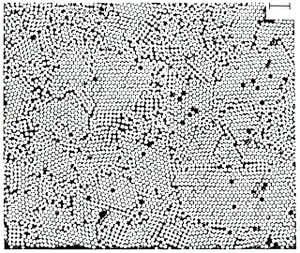

- Under certain chemical conditions (typically in base-catalyzed sols), the particles may grow to sufficient size to become colloids, which are affected both by sedimentation and forces of gravity. Stabilized suspensions of such sub-micrometre spherical particles may eventually result in their self-assembly—yielding highly ordered microstructures reminiscent of the prototype colloidal crystal: precious opal. [7][8]

- Under certain chemical conditions (typically in acid-catalyzed sols), the interparticle forces have sufficient strength to cause considerable aggregation and/or flocculation prior to their growth. The formation of a more open continuous network of low density polymers exhibits certain advantages with regard to physical properties in the formation of high performance glass and glass/ceramic components in 2 and 3 dimensions. [9]

In either case (discrete particles or continuous polymer network) the sol evolves then towards the formation of an inorganic network containing a liquid phase (gel). Formation of a metal oxide involves connecting the metal centers with oxo (M-O-M) or hydroxo (M-OH-M) bridges, therefore generating metal-oxo or metal-hydroxo polymers in solution.

In both cases (discrete particles or continuous polymer network), the drying process serves to remove the liquid phase from the gel, yielding a micro-porous amorphous glass or micro-crystalline ceramic. Subsequent thermal treatment (firing) may be performed in order to favor further polycondensation and enhance mechanical properties.

With the viscosity of a sol adjusted into a proper range, both optical quality glass fiber and refractory ceramic fiber can be drawn which are used for fiber optic sensors and thermal insulation, respectively. In addition, uniform ceramic powders of a wide range of chemical composition can be formed by precipitation.

Polymerization

Metal alkoxides are members of the family of organometallic compounds, which are organic compounds which have one or more metal atoms in the molecule. Metal alkoxides (R-O-M) are like alcohols (R-OH) with a metal atom, M, replacing the hydrogen H in the hydroxyl group. They constitute the class of chemical precursors most widely used in sol-gel synthesis. The formation of a metal oxide involves connecting the metal centers with oxo (M-O-M) or hydroxo (M-OH-M) bridges, therefore generating metal-oxo or metal-hydroxo polymers in solution.

The most common mineral in the earth’s crust is silicon dioxide (or silica), SiO2. There are at least seven different crystalline forms of silica, including quartz. The basic building block of all of these crystalline forms of silica is the SiO4 tetrahedron. Since each tetrahedron shares 2 of its edges with other SiO4 tetrahedra, the overall ratio of oxygen to silicon is 2:1 instead of 4:1 (thus SiO2). The intricate and highly specific geometry of this network of tetrahedra takes years to form under incredible terrestrial pressures at great depth. That is why SiO2 is such a good glass former. Crystallization in a reasonable amount of time under the most ideal laboratory conditions is highly unlikely. Thus, amorphous silica is the major component of nearly all window glass.

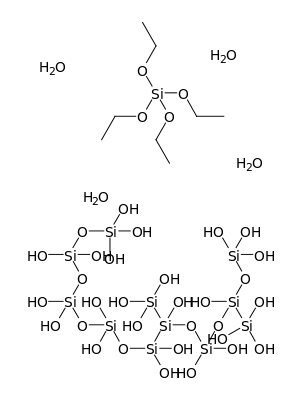

A well studied alkoxide is silicon tetraethoxide, or tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS). The chemical formula for TEOS is given by: Si(OC2H5)4, or Si(OR)4 where the alkyl group R = C2H5. Alkoxides are ideal chemical precursors for sol-gel synthesis because they react readily with water. The reaction is called hydrolysis, because a hydroxyl ion becomes attached to the silicon atom as follows:

- Si(OR)4 + H2O → HO-Si(OR)3 + R-OH

Depending on the amount of water and catalyst present, hydrolysis may proceed to completion, so that all of the OR groups are replaced by OH groups, as follows:

- Si(OR)4 + 4 H2O → Si(OH)4 + 4 R-OH

Any intermediate species [(OR)2–Si-(OH)2] or [(OR)3–Si-(OH)] would be considered the result of partial hydrolysis. In addition, two partially hydrolyzed molecules can link together in a condensation reaction to form a siloxane [Si–O–Si] bond:

- (OR)3–Si-OH + HO–Si-(OR)3 → [(OR)3Si–O–Si(OR)3] + H-O-H

or

- (OR)3–Si-OR + HO–Si-(OR)3 → [(OR)3Si–O–Si(OR)3] + R-OH

Thus, polymerization is associated with the formation of a 1, 2, or 3- dimensional network of siloxane [Si–O–Si] bonds accompanied by the production of H-O-H and R-O-H species.

By definition, condensation liberates a small molecule, such as water or alcohol. This type of reaction can continue to build larger and larger silicon-containing molecules by the process of polymerization. Thus, a polymer is a huge molecule (or macromolecule) formed from hundreds or thousands of units called monomers. The number of bonds that a monomer can form is called its functionality. Polymerization of silicon alkoxide, for instance, can lead to complex branching of the polymer, because a fully hydrolyzed monomer Si(OH)4 is tetrafunctional (can branch or bond in 4 different directions). Alternatively, under certain conditions (e.g., low water concentration) fewer than 4 of the OR or OH groups (ligands) will be capable of condensation, so relatively little branching will occur. The mechanisms of hydrolysis and condensation, and the factors that bias the structure toward linear or branched structures are the most critical issues of sol-gel science and technology. [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16][17]

Nanomaterials

In the processing of fine ceramics, the irregular particle sizes and shapes in a typical powder often lead to non-uniform packing morphologies that result in packing density variations in the powder compact. Uncontrolled agglomeration of powders due to attractive van der Waals forces can also give rise to microstructural inhomogeneities. [18][19]

Differential stresses that develop as a result of non-uniform drying shrinkage are directly related to the rate at which the solvent can be removed, and thus highly dependent upon the distribution of porosity. Such stresses have been associated with a plastic-to-brittle transition in consolidated bodies, [20] and can yield to crack propagation in the unfired body if not relieved.

In addition, any fluctuations in packing density in the compact as it is prepared for the kiln are often amplified during the sintering process, yielding inhomogeneous densification. Some pores and other structural defects associated with density variations have been shown to play a detrimental role in the sintering process by growing and thus limiting end-point densities. Differential stresses arising from inhomogeneous densification have also been shown to result in the propagation of internal cracks, thus becoming the strength-controlling flaws.[21][22][23][24][25]

It would therefore appear desirable to process a material in such a way that it is physically uniform with regard to the distribution of components and porosity, rather than using particle size distributions which will maximize the green density. The containment of a uniformly dispersed assembly of strongly interacting particles in suspension requires total control over particle-particle interactions. Monodisperse colloids provide this potential. [26] [27] [28]

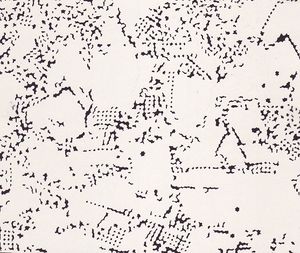

Monodisperse powders of colloidal silica, for example, may therefore be stabilized sufficiently to ensure a high degree of order in the colloidal crystal or polycrystalline colloidal solid which results from aggregation. The degree of order appears to be limited by the time and space allowed for longer-range correlations to be established. Such defective polycrystalline structures would appear to be the basic elements of nanoscale materials science, and, therefore, provide the first step in developing a more rigorous understanding of the mechanisms involved in microstructural evolution in inorganic systems such as sintered ceramic nanomaterials. [29] [30]

Applications

The applications for sol gel-derived products are numerous. [31][32][33][34][35][36] For example, scientists have used it to produce the world’s lightest materials and also some of its toughest ceramics. One of the largest application areas is thin films, which can be produced on a piece of substrate by spin coating or dip coating. Other methods include spraying, electrophoresis, inkjet printing or roll coating.

With the viscosity of a sol adjusted into a proper range, both optical and refractory ceramic fibers can be drawn which are used for fiber optic sensors and thermal insulation, respectively. Thus, many ceramic materials, both glassy and crystalline, have found use in various forms from bulk solid-state components to high surface area forms such as thin films, coatings and fibers. [9] [37] Protective and decorative coatings, and electro-optic components can be applied to glass, metal and other types of substrates with these methods. Cast into a mold, and with further drying and heat-treatment, dense ceramic or glass articles with novel properties can be formed that cannot be created by any other method.

Ultra-fine and uniform ceramic powders can be formed by precipitation. These powders of single and multiple component compositions can be made in sub-micrometre particle size for dental and biomedical applications. Composite powders have been patented for use as agrochemicals and herbicides. Powder abrasives, used in a variety of finishing operations, are made using a sol-gel type process. One of the more important applications of sol-gel processing is to carry out zeolite synthesis. Other elements (metals, metal oxides) can be easily incorporated into the final product and the silicate sol formed by this method is very stable.

Another application in research is to entrap biomolecules for sensory (biosensors) or catalytic purposes, by physically or chemically preventing them from leaching out and, in the case of protein or chemically-linked small molecules, by shielding them from the external environment yet allowing small molecules to be monitored. The major disadvantages are that the change in local environment may alter the functionality of the protein or small molecule entrapped and that the synthesis step may damage the protein. To circumvent this, various strategies have been explored, such as monomers with protein friendly leaving groups (e.g. glycerol) and the inclusion of polymers which stabilize protein (e.g. PEG).[38]

Other products fabricated with this process include various ceramic membranes for microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, pervaporation and reverse osmosis. If the liquid in a wet gel is removed under a supercritical condition, a highly porous and extremely low density material called aerogel is obtained. Drying the gel by means of low temperature treatments (25-100 °C), it is possible to obtain porous solid matrices called xerogels. In addition, a sol-gel process was developed in the 1950s for the production of radioactive powders of UO2 and ThO2 for nuclear fuels, without generation of large quantities of dust.

Opto-mechanical

Macroscopic optical elements and active optical components as well as large area hot mirrors, cold mirrors, lenses and beam splitters all with optimal geometry can be made quickly and at low cost via the sol-gel route. In the processing of high performance ceramic nanomaterials with superior opto-mechanical properties under adverse conditions, the size of the crystalline grains is determined largely by the size of the crystalline particles present in the raw material during the synthesis or formation of the object. Thus a reduction of the original particle size well below the wavelength of visible light (~ 0.5 µm or 500 nm) eliminates much of the light scattering, resulting in a translucent or even transparent material.

Furthermore, results indicate that microscopic pores in sintered ceramic nanomaterials, mainly trapped at the junctions of microcrystalline grains, cause light to scatter and prevented true transparency. it has been observed that the total volume fraction of these nanoscale pores (both intergranular and intragranular porosity) must be less than 1% for high-quality optical transmission. I.E. The density has to be 99.99% of the theoretical crystalline density. [39] [40]

One example of such a material is that which has ben developed by researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Ceramic Technologies and Sintered Materials. This sintered alumina nanomaterial is very hard and virtually transparent over a range of wavelengths. Yet like other sintered materials using larger particles of larger diameter and less sophisticated processing methodologies, it can be produced at temperatures (1000-1200 °C) much lower than its melting point (2070 °C).

Tests have clearly shown that the transparent nanomaterials have exceeded all expectations. For example, the amount of scattered light in the nanomaterials is similar to that measured from single crystalline Nd:YAG components. This is due primarily to the fact that grain boundaries, which act as the primary scattering centers in this theoretically dense material, measure something less than 1 nm in average width. In addition, the nanomaterials have exhibited no more wavefront distortion than that expected from surface polishing.

One research team has found that laser amplifier slabs made from nanomaterials offer several advantages over those made from single crystals. Perhaps most basic is that these slabs can be obtained in a regular, timely fashion without unexpected additional costs. Nanomaterials are more easily fabricated into larger sizes for greater pwoer and they can also be made any size and shape -- limited only by the size of the sintering furnace. The time required to produce such slabs of optically transparent nanomaterials is much shorter than the time to grow crystal boules of the same chemical composition. E.G. Nanomaterials may be fabricated in several days, whereas it would take several weeks to grow single crystals of similar chemical composition.[41]

Slabs made form nanomaterials are exhibit a higher value of fracture toughness (and stress intensity factor, KIc) than single-seed crystal slabs and musch laess prone to undergo a catastrophic failure or fracture. I.E. When a crstalline slab fractures, the propagation of primary crack is virtually unimpeded, yielding a large (and fairly linear) path of least resistance. Thus, the crack can eaisly "run", extending some distance from the original crack site and often branching or making a random turn towards the center of the crystal in order to relieve internal stress. In fine-grained nanomaterials, because crack propagation is impeded by grain boundaries, resistance to fracture is significant. Nanomaterials also exhibit lower residual stress, as evidenced by the increased distortion of the laser beam in crystalline materials, which can be a contributing factor to failure of the materials.[41]

Nanomaoterials can accommodate higher concentrations of dopaants (rare earth ions such as neodymium Nd3+ or yterbium Yb3+) which could permit pumping at wavelengths that might otherwise be impractical. Dopant concntraitons are quite homogeneous in nanomaterials and be prisely controlled. In crystals, dopants tend to segregate preferentially towards the bottom of the growing boule.[41]

Nanomaterials also provide the possibility of novel composite stuctures. The different materials would be co-sintered in order to produce a single (monolithic) integral structure. Another possible approach is to embed different powders with the same host before sintering the slab in order to create a progressive and continuous concentration gradient of the dopant ions -- a molecular configuration evidenced in some phase transformations in solids which proceed by the mechanism of spinodal decomposition.[41]

See also

- Ceramic engineering

- Colloidal crystal

- Glass transition

- Nanomaterials

- Nanoparticle

- Nanotechnology

- Optical fiber

- Photonic crystal

- Physics of glass

- Polymer

- Polymerization

- Rheology

- Transparent ceramics

- Transparent materials

References

- ↑ Brinker, C.J.; G.W. Scherer (1990). Sol-Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol-Gel Processing. Academic Press. ISBN 0121349705.

- ↑ Hench, L.L.; J.K. West (1990). "The Sol-Gel Process". Chemical Reviews 90: 33.

- ↑ Klein, L. (1994). Sol-Gel Optics: Processing and Applications. Springer Verlag. ISBN 0792394240. http://books.google.com/?id=wH11Y4UuJNQC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Klein, L.C. and Garvey, G.J., "Kinetics of the Sol-Gel Transition" Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, Vol. 38, p.45 (1980)

- ↑ Brinker, C.J., et al., "Sol-Gel Transition in Simple Silicates", J. Non-Crystalline Solids, Vol.48, p.47 (1982)

- ↑ Einstein, A., Ann. Phys., Vol. 19, p. 289 (1906), Vol. 34 p.591 (1911)

- ↑ Allman III, R.M., Structural Variations in Colloidal Crystals, M.S. Thesis, UCLA (1983)

- ↑ Allman III, R.M. and Onoda, G.Y., Jr. (Unpublished work, IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, 1984)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sakka, S. et al., "The Sol-Gel Transition: Formation of Glass Fibers & Thin Films", J. Non-Crystalline Solids, Vol. 48, p.31 (1982)

- ↑ Dislich, H., Glass. Tech. Berlin., Vol.44, p.1 (1971); Dislich, Helmut (1971). "New Routes to Multicomponent Oxide Glasses". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 10: 363. doi:10.1002/anie.197103631.

- ↑ Matijevic, Egon. (1986). "Monodispersed colloids: art and science". Langmuir 2: 12. doi:10.1021/la00067a002.

- ↑ Brinker, C. J.; Mukherjee, S. P. (1981). "Conversion of monolithic gels to glasses in a multicomponent silicate glass system". Journal of Materials Science 16: 1980. doi:10.1007/BF00540646.

- ↑ Sakka, S; Kamiya, K (1980). "Glasses from metal alcoholates". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 42: 403. doi:10.1016/0022-3093(80)90040-X.

- ↑ Yoldas, B. E. (1979). "Monolithic glass formation by chemical polymerization". Journal of Materials Science 14: 1843. doi:10.1007/BF00551023.

- ↑ Prochazka, S.; Klug, F. J. (1983). "Infrared-Transparent Mullite Ceramic". Journal of the American Ceramic Society 66: 874. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb11004.x.

- ↑ Ikesue, Akio; Kinoshita, Toshiyuki; Kamata, Kichiro; Yoshida, Kunio (1995). "Fabrication and Optical Properties of High-Performance Polycrystalline Nd:YAG Ceramics for Solid-State Lasers". Journal of the American Ceramic Society 78: 1033. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1995.tb08433.x.

- ↑ Ikesue, A (2002). "Polycrystalline Nd:YAG ceramics lasers". Optical Materials 19: 183. doi:10.1016/S0925-3467(01)00217-8.

- ↑ Onoda, G.Y. and Hench, L.L., Ceramic Processing Before Firing (Wiley & Sons, New York, 1979)

- ↑ Aksay, I.A., Lange, F.F., Davis, B.I. (1983). "Uniformity of Al2O3-ZrO2 Composites by Colloidal Filtration". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 66: C-190. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb10550.x.

- ↑ Franks, G.V. and Lange, F.F. (1996). "Plastic-to-Brittle Transition of Saturated, Alumina Powder Compacts". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 79: 3161. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1996.tb08091.x.

- ↑ Evans, A.G. and Davidge, R.W. (1969). "The strength and fracture of fully dense polycrystalline magnesium oxide". Phil. Mag. 20 (164): 373. doi:10.1080/14786436908228708.

- ↑ Evans, A.G. and Davidge, R.W. (1970). "Strength and fracture of fully dense polycrystalline magnesium oxide". Journal of Materials Science 5: 314.

- ↑ J Mat. Sci. 5: 314. 1970.

- ↑ Lange, F.F. and Metcalf, M. (1983). "Processing-Related Fracture Origins: II, Agglomerate Motion and Cracklike Internal Surfaces Caused by Differential Sintering". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 66: 398. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb10069.x.

- ↑ Evans, A.G. (1987). "Considerations of Inhomogeneity Effects in Sintering". Journal of the American Ceramics Society 65: 497.

- ↑ Allman III, R.M., Structural Variations in Colloidal Crystals, M.S. Thesis, UCLA (1983)

- ↑ Allman III, R.M. in Microstructural Control Through Colloidal Consolidation, Aksay, I.A., Adv. Ceram., Vol. 9, p. 94, Proc. Amer. Ceramic Soc. (Columbus, OH 1984)

- ↑ Allman III, R.M. and Onoda, G.Y., Jr. (Unpublished work, IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, 1984)

- ↑ Whitesides, G.M., et al. (1991). "Molecular Self-Assembly and Nanochemistry: A Chemical Strategy for the Synthesis of Nanostructures". Science 254: 1312. doi:10.1126/science.1962191.

- ↑ Dubbs D. M, Aksay I.A. (2000). "Self-Assembled Ceramics". Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 51: 601. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.601. PMID 11031294.

- ↑ Wright, J.D. and Sommerdijk, N.A.J.M., Sol-Gel Materials: Chemistry and Applications

- ↑ Aegerter, M.A. and Mennig, M., Sol-Gel Technologies for Glass Producers and Users

- ↑ Philippou, J., Sol-Gel: A Low temperature Process for the Materials of the New Millennium (2000)

- ↑ Brinker, C.J. and Scherer, G.W., Sol-Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol-Gel Processing, (Academic Press, 1990)

- ↑ German Patent 736411 (Granted 6 May 1943) Anti-Reflective Coating (W. Geffcken and E. Berger, Jenaer Glasswerk Schott)

- ↑ Klein, L.C., Sol-Gel Optics: Processing and Applications, Springer Verlag (1994)

- ↑ Patel, P.J., et al., (2000) "Transparent ceramics for armor and EM window applications", Proc. SPIE, Vol. 4102, p. 1, Inorganic Optical Materials II, Marker, A.J. and Arthurs, E.G., Eds.

- ↑ Gupta R, Chaudhury NK (2007). "Entrapment of biomolecules in sol-gel matrix for applications in biosensors: problems and future prospects". Biosens Bioelectron 22 (11): 2387. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2006.12.025. PMID 17291744.

- ↑ Yoldas, B. E. (1979). "Monolithic glass formation by chemical polymerization". Journal of Materials Science 14: 1843. doi:10.1007/BF00551023.

- ↑ Prochazka, S.; Klug, F. J. (1983). "Infrared-Transparent Mullite Ceramic". Journal of the American Ceramic Society 66: 874. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb11004.x.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Transparent Ceramics Spark Laser Technology, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories (S&TR, 2006)

Further reading

- Colloidal Dispersions, Russel, W.B., et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press (1989)

- Glasses and the Vitreous State, Zarzycki. J., Cambridge University Press, 1991

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||