Spica

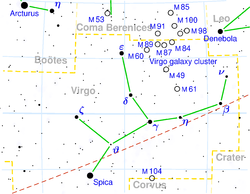

Location of Spica (bottom left of center) |

|

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 |

|

|---|---|

| Constellation | Virgo |

| Pronunciation | /ˈspaɪkə/ |

| Right ascension | 13h 25m 11.5793s[1] |

| Declination | −11° 09′ 40.759″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +1.04 |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | B1 III-IV/B2 V[2] |

| U−B color index | −0.94[3] |

| B−V color index | −0.24[3] |

| Variable type | β Cep, Rotating ellipsoid |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +1.0[4] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −42.50[1] mas/yr Dec.: −31.73[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 12.44 ± 0.86[1] mas |

| Distance | 260 ± 20 ly (80 ± 6 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −3.55 (−3.5/−1.5)[5] |

| Orbit[6] | |

| Period (P) | 4.0145898 d |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.067 ± 0.014 |

| Inclination (i) | 54 ± 6° |

| Periastron epoch (T) | 2440678.09 |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) |

140 ± 10° |

| Details | |

| Primary | |

| Mass | 10.25 ± 0.68[6] M☉ |

| Radius | 7.40 ± 0.57[6] R☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 3.7 ± 0.1[5] |

| Luminosity | 12,100[7] L☉ |

| Temperature | 22,400[5] K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 199 ± 5[6] km/s |

| Secondary | |

| Mass | 6.97 ± 0.4[6] M☉ |

| Radius | 3.64 ± 0.28[6] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 1,500[7] L☉ |

| Temperature | 18,500[7] K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 87 ± 6[6] km/s |

| Other designations | |

Spica (α Vir / α Virginis / Alpha Virginis) is the brightest star in the constellation Virgo, and the 15th brightest star in the nighttime sky. It is 260 light years distant from Earth. A blue giant, it is a variable of the Beta Cephei type.

Contents |

Observation history

Spica is believed to be the star that provided Hipparchus with the data which enabled him to discover precession of the equinoxes.[9] A temple to Menat (an early Hathor) at Thebes was oriented with reference to Spica when it was constructed in 3200 BC and, over time, precession resulted in a slow but noticeable change in the location of Spica relative to the temple.[10] Nicolaus Copernicus made many observations of Spica with his home-made triquetrum for his researches on precession.[11][12]

As one of the nearest massive binary star systems to the Sun, Spica has been the subject of many observational studies.[13]

Characteristics

Spica is a close binary star system that orbit about each other every four days. They remain sufficiently close together that they can not be resolved as individual stars through a telescope. The changes in the orbital motion of this pair results in a Doppler shift in the absorption lines of their respective spectra, making them a double-lined spectroscopic binary.[6] Initially, the orbital parameters for this system were inferred using spectroscopic measurements. Between 1966 and 1970, the Narrabri interferometer was used to observe the pair, and to directly measure the orbital characteristics and the angular diameter of the primary. The latter was determined to be (0.90 ± 0.04) × 10−3 arcseconds, while the angular size of the semimajor axis of the orbit was found to be only slightly larger at (1.54 ± 0.05) × 10−3 arcseconds.[5]

The primary star has a stellar classification of B1 III-IV. The luminosity class matches the spectrum of a star that is midway between a subgiant and a giant star, and it is no longer a B-type main sequence star.[2] This is a massive star with more than 10 times the mass of the Sun and seven times the Sun's radius. The total luminosity of this star is about 12,100 times that of the Sun, and eight times the luminosity of its companion. The primary is one of the nearest stars to the Sun that has sufficient mass to end its life in a Type II supernova explosion.[7]

The primary is classified as a Beta Cephei type variable star that varies in brightness over a 0.1738 day period. The spectrum shows a radial velocity variation with the same period, indicating that the surface of the star is regularly pulsating outward and then contracting. This star is rotating rapidly, with a rotational velocity of 199 km/s along the equator.[6]

The secondary member of this system is one of the few stars to display the Struve-Sahade Effect. This is an anomalous change in the strength of the spectral lines over the course of an orbit, where the lines become weaker as the star is moving away from the observer.[13] It may be caused by a strong stellar wind from the primary scattering the light from secondary when it is receding.[14] This star is smaller than the primary, with about 7 times the mass of the Sun and 3.6 times the Sun's radius.[6] It's stellar classification is B2 V, making this a main sequence star.[2]

Spica is a rotating ellipsoidal variable, which is a non-eclipsing close binary star system where the stars are mutually distorted through their gravitational interaction. This effect causes the apparent magnitude of the star system to vary by 0.03 over a time interval that matches the orbital period. This slight dip in magnitude is barely noticeable visually.[15] The rotation rates of both stars are faster than their mutual orbital period. This lack of synchronization and the high ellipticity of their orbit may indicate that this is a young star system. Over time, the mutual tidal interaction of the pair may lead to rotational synchronization and orbit circularization.[16]

Visibility

Located close to the ecliptic, Spica can be occulted by the Moon and sometimes by the planets. The last planetary occultation of Spica occurred when Venus passed in front of the star (as seen from Earth) on November 10, 1783. The next occultation will occur September 2, 2197, when Venus again passes in front of Spica. The Sun passes a little more than 2° north of Spica around October 16 every year, and the star's heliacal rising occurs about two weeks later. Every 8 years, Venus passes Spica around the time of the star's heliacal rising, as in 2009 when it passed 3.5° north of the star on November 3.[17]

A method of finding Spica is to follow the arc of the handle of the Big Dipper to Arcturus, and then continue on the same angular distance to Spica. This can be recalled by the mnemonic phrase, "follow the arc to Arcturus and speed on to Spica."

Etymology and cultural significance

The name Spica derives from Latin spīca virginis "Virgo's ear of grain" (usually wheat). In Chinese astronomy, the star is known as Jiao Xiu 1 (角宿一) in Jiao Xiu, one of the Chinese constellations. In Hindu astronomy, Spica corresponds to the Nakshatra Chitra. The 17th century German astronomer Bayer and others referred to the star as Arista.

Medieval names include Azimech, from Arabic السماك الأعزل al-simāk al-a‘zal 'the Undefended', and Alarph, Arabic for 'the Grape Gatherer'.

In medieval astrology, it was a Behenian fixed star, associated with the emerald and sage. In his De Occulta Philosophia, Cornelius Agrippa attributes its kabbalistic symbol ![]() to Hermes Trismegistus.

to Hermes Trismegistus.

A blue star represents Spica on the flag of the Brazilian state of Pará. Spica is also the star representing Pará on the Brazilian flag.

Spica was used in the novel Pushing Ice by Alastair Reynolds as the distant star to which the protagonists are carried by alien technology.

The Japanese manga and series Twin Spica was named after the star. Spica is two stars that circle each other, though from a distance they appear as one, which parallels the series' running theme of friendship.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Perryman, M. A. C.; et al. (April 1997). "The HIPPARCOS Catalogue". Astronomy & Astrophysics 323: L49–L52. Bibcode: 1997A&A...323L..49P.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Schnerr, R. S.; et al. (June 2008). "Magnetic field measurements and wind-line variability of OB-type stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 483 (3): 857–867. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077740. Bibcode: 2008A&A...483..857S. http://remote.science.uva.nl/~rschnerr/papers/OBstars.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Pfleiderer, J.; Mayer, U. (October 1971). "Near-ultraviolet surface photometry of the southern Milky Way". Astronomical Journal 76: 691. doi:10.1086/111186. Bibcode: 1971AJ.....76..691P.

- ↑ Wilson, Ralph Elmer (1953). General Catalogue of Stellar Radial Velocities. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. Bibcode: 1953QB901.W495......

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Herbison-Evans, D.; Hanbury Brown, R.; Davis, J.; Allen, L. R. (1971). "A study of alpha Virginis with an intensity interferometer". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 151: 161−176. Bibcode: 1971MNRAS.151..161H.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Harrington, David; Koenigsberger, Gloria; Moreno, Edmundo; Kuhn, Jeffrey (October 2009). "Line-profile Variability from Tidal Flows in Alpha Virginis (Spica)". The Astrophysical Journal 704 (1): 813–830. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/704/1/813. Bibcode: 2009ApJ...704..813H.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Kaler, Jim. "Spica". Stars. http://stars.astro.illinois.edu/sow/spica.html. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ↑ "V* alf Vir -- Variable Star of beta Cep type". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=alf+Vir. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. Oxford University Press. pp. 259. ISBN 0195095391.

- ↑ Allen, Richard Hinckley (2003). Star Names and Their Meanings. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 468. ISBN 0766140288.

- ↑ Rufus, W. Carl (April 1943). "Copernicus, Polish Astronomer, 1473–1543". The Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 37 (4): 134. Bibcode: 1943JRASC..37..129R.

- ↑ Moesgaard, Kristian P. (1973). "Copernican influence on Tycho Brahe". In Jerzy Dobrzycki. The reception of Copernicus' heliocentric theory: proceedings of a symposium organized by the Nicolas Copernicus Committee of the International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science. Toruń, Poland: Studia Copernicana, Springer. ISBN 9027703116. http://books.google.com/books?id=tAWp34_GYLAC&pg=PA35&dq=copernicus+spica#v=onepage&q=copernicus%20spica&f=false.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Riddle, R. L.; Bagnuolo, W. G.; Gies, D. R. (December 2001). "Spectroscopy of the temporal variations of α Vir". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 33: 1312. Bibcode: 2001AAS...199.0613R.

- ↑ Gies, Douglas R.; Bagnuolo, William G., Jr.; Penny, Laura R. (April 1997). "Photospheric Heating in Colliding-Wind Binaries". Astrophysical Journal 479: 408. doi:10.1086/303848. Bibcode: 1997ApJ...479..408G.

- ↑ Morris, S. L. (August 1985). "The ellipsoidal variable stars". Astrophysical Journal, Part 1 295: 143–152. doi:10.1086/163359. Bibcode: 1985ApJ...295..143M.

- ↑ Beech, M. (August 1986). "The ellipsoidal variables. III - Circularization and synchronization". Astrophysics and Space Science 125 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1007/BF00643972. Bibcode: 1986Ap&SS.125...69B.

- ↑ Breit, Derek C. (March 12, 2010). "Diary of Astronomical Phenomena 2010". Poyntsource.com. http://www.poyntsource.com/New/Diary.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||