Spitsbergen

Map of Svalbard with Spitsbergen in the west emphasised |

|

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Arctic Ocean |

| Archipelago | Svalbard |

| Area | 39,044 km2 (15,075 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 36th |

| Highest elevation | 1,717 m or 5,633 ft |

| Highest point | Newtontoppen |

| Country | |

|

Norway

|

|

| Largest city | Longyearbyen |

Spitsbergen is a Norwegian island, the largest island of the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. The island of Spitsbergen covers approximately 39,044 km² (15,075 square miles).[1] This name was also formerly applied to the entire archipelago of Svalbard and occasionally still is. It is around 450 km (280 miles) long and between 40 and 225 km (25 and 140 miles) wide. As Spitsbergen lies far within the arctic circle, the Sun is always above the horizon from late April to late August. From 26 October to 15 February the Sun is always below the horizon, and from 12 November to the end of January there is civil polar night, when it is always so dark that artificial light must be used at all times.

Contents |

Etymology

Spitsbergen was named by its discoverer Willem Barentsz in 1596, the name meaning “pointed mountains” (from the Dutch Spits - "pointed", Bergen-"mountains")), the name being applied to both the main island and the island group as a whole. The islands were known as "Greenland" in English during the 17th Century [2] They were referred to as Spitzbergen in a translation of a text by Martens, in 1694, and this became the English name thereafter. The Arctic explorer WM Conway, in 1906, was of the opinion this was incorrect [3] though this had little effect on British practice[4] [5] In 1920 the treaty determining the fate of the islands was entitled the "Spitsbergen Treaty", and the islands were referred to in the USA as "Spitsbergen" from that time,[6] though "Spitzbergen" remained the common British spelling throughout the 20th century.[7] Under Norwegian governance the islands were named "Svalbard" in 1925, the main island becoming "Spitsbergen", and by the end of the 20th century this usage had become general.

History

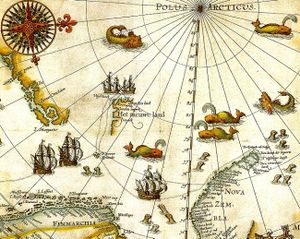

The first confirmed sighting of the island was by Willem Barentsz, who came across it while searching for the Northern Sea Route in 1596. However, this archipelago may have been known to Russian Pomor hunters as early as the 14th or 15th century, though solid evidence from before the 17th century is lacking. Following the English whalers and others in referring to the archipelago as Greenland, they named it Grumant (Грумант). The name Svalbard is first mentioned in Icelandic sagas of the 10th and 11th centuries, but they more likely refer to Jan Mayen or even Greenland.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Early claims

Early whaling expeditions to Svalbard in general and Spitsbergen in particular tended, because of currents and fauna, to cluster around the western coast of Spitsbergen and the islands off-shore. Shortly after whaling began (1611), the Danish crown claimed ownership (1616) of Jan Mayen and the Spitsbergen islands, as all of Svalbard was then known. But in 1613, the English Muscovy Company had done the same. The primary and most profitable whaling grounds of this joint-stock company came to be centered around Spitsbergen in the early 17th Century, and the company's royal charter of 1613 granted a monopoly on whaling in Spitsbergen, based on the (erroneous) claim that Hugh Willoughby had discovered the land in 1553.[8][9] Not only had they wrongly assumed a 1553 English voyage had reached the area, but on 27 June 1607, during his first voyage in search of a "northeast passage" on behalf of the company, Henry Hudson sighted "Newland" (i.e. Spitsbergen), near the mouth of the great bay Hudson later simply named the Great Indraught (Isfjorden). In this way the English hoped to head off expansion by the Dutch in the region, at the time their major rival.[10][11] Initially the English tried to drive away competitors; but after disputes with the Dutch (1613–24), they, for the most part, only claimed the bays south of Kongsfjorden.[12]

Danish expansion

From 1617 onwards, a Danish-chartered company began sending whaling fleets to Spitsbergen.[13] This successful expansion by Copenhagen into the North Atlantic has recently been cited by historians as the first step of the Danish-Norwegian state into overseas colonialism, which eventually built a small 17th century empire of East Indian trade posts, North Atlantic possessions (such as Greenland and Iceland) and a small Atlantic trade route between possessions on the Guinea Coast (in modern Ghana) and what is now the U.S. Virgin Islands.[14][15]

The entire Svalbard archipelago, nominally ruled first by Denmark–Norway, and later the Norwegians (as Union between Sweden and Norway from 1814–1905, independent Norway from 1905), remained a source of riches for fishery and whaling vessels from many nations. The islands also became the launching point for a number of Arctic explorers, including Roald Amundsen and Ernest Shackleton.

Spitsbergen Treaty

The Spitsbergen Treaty of February 9, 1920, recognises the full and absolute sovereignty of Norway over all the arctic archipelago of Svalbard. The exercise of sovereignty is, however, subject to certain stipulations, and not all Norwegian law applies. Originally limited to nine signatory nations, over 40 are now signatories of the treaty. Citizens of any of the signatory countries may settle in the archipelago. Currently, only Norway and Russia make use of this right.

Once named Spitsbergen for its largest island, the Svalbard was made a part of Norway—not a dependency—by the Svalbard Act of 1925. Since this date it has been a portion of Norway, with a Norwegien appointed Governor resident at the capitol of Longyearbyen, albeit with limitiations on the imposition of certain Norwegian laws as outlined in the Spitsbergen Treaty.

The largest settlement on Spitsbergen is the Norwegian town of Longyearbyen, while the second largest settlement is the Russian coal mining settlement of Barentsburg (which was sold by the Netherlands in 1932 to the Soviet company Arktikugol). Other settlements on the island include the former Russian mining communities of Grumantbyen and Pyramiden (abandoned in 1961 and 1998, respectively), a Polish research station at Hornsundet, and the remote northern settlement of Ny-Ålesund.[16]

World War II

Allied soldiers were stationed on the island in 1941 to prevent Nazi Germany from occupying the islands. While the island had officially been ceded to Norway in the 1920s, that country fell under German occupation in 1940. The majority of inhabitants on the island were Russian (Soviet Union had a non-aggression pact with Germany until June 22, 1941). The United Kingdom and Canada sent military forces to the island to destroy installations, mainly Soviet coal mines, and prevent the Germans from occupying it.[17]

The German battleship Tirpitz and an escort flotilla shelled and destroyed the Allied weather station there in Operation Sizilien in 1943. On 6 September, a squadron consisting of Tirpitz, Scharnhorst and nine destroyers weighed anchor in Altenfjord and Kåfjord and headed for Spitsbergen, to attack the Allied base there. At dawn on 8 September 1943 Tirpitz and Scharnhorst opened fire against the two 3-in guns which comprised the defences of Barentsburg, and the destroyers ran inshore with landing parties. Before noon it was all over. Some prisoners had been taken, a supply dump destroyed, the wireless station wrecked and the landing parties had returned on board. The German ships returned safely to Altenfjord and Kåfjord on 9 September 1943. Although those on board did not yet know it, Tirpitz had carried out her last operation.[18]

Ecology

Polar bears are found in the Spitsbergen area, particularly on Storfjorden coast vicinity.[19] moreover, the sub-population of Ursus maritimus found here is a genetically distinct taxon of polar bears associated with the Barents Sea region.[20] Edgeøya lies to the southeast of Spitsbergen. This uninhabited island is the largest part of the South East Svalbard Nature Reserve, home to polar bears and reindeer.

Kvadehuksletta, on western Spitsbergen, is notable for its unique stone structures, including very circular stones and labyrinthine patterns ("patterned ground"). These structures are believed to be the result of frost heaving.

Polish Polar Station

The station was erected in July 1957 by the Polish Academy of Sciences Expedition within the framework of the International Geophysical Year. The expedition was led by Stanislaw Siedlecki, geologist, explorer and climber, a veteran of Polish Arctic expeditions in the 1930s (including the first traverse of West Spitsbergen island). A reconnaissance group searching the area for the future station site had been working in Hornsund in the previous summer, and selected the flat marine terrace in Isbjørnhamna. The research station was constructed during three summer months in 1957.

The station was modernized in 1978, in order to resume a year-round activity. Since then, the Institute of Geophysics of the Polish Academy of Sciences has been responsible for organising year-round and seasonal research expeditions to the station.

Seed Vault

The Norwegian government has built a "doomsday" seed bank to store seeds from as many of the world's plant species as possible. The bank was created by hollowing out a 120-metre (390 ft) tunnel on Spitsbergen cut into rock with a natural temperature of −6 °C (21 °F), refrigerating it to −18 °C (−0 °F), and then storing seeds donated by the 1,400 crop repositories maintained by countries around the world. The vault has top security blast-proof doors and two airlocks. The number of seeds stored depends on the number of countries participating in the project, but the first seeds arrived late in 2007. The point of this project is to save plants (wild, agricultural, etc.) from becoming extinct as a side-effect of crop gene manipulation, or due to a global catastrophe such as climate change (the tunnel is 130 metres above sea-level) or nuclear war.[21]

Fossil Find

Between 2007-2008, researchers from the University of Oslo uncovered the fossil remains of the largest known pliosaur on Spitsbergen. The team held off on announcing the discovery until two sets were found. The find, for now dubbed "Predator X", probably represents a new genus, and possibly a new family of pliosaurs.[22]

The island's three-week excavation season and difficult field conditions mean that the fossil resources have so far gone largely untapped. However, a member of the expedition said that Spitsbergen has "one of the most important localities of extinct marine reptiles in the world."[22]

In popular culture

- In the fairy tale, The Snow Queen, this is the location of the Snow Queen's palace.

- In The Call of the Wild, by Jack London; Ch. 1, Into the Primitive: "In the 'tween-decks of the Narwhal, Buck and Curly joined two other dogs. One of them was a big, snow-white fellow from Spitzbergen who had been brought away by a whaling captain, and who had later accompanied a Geological Survey into the Barrens."

- Spitsbergen is the location of the fictional 'Spitzbergen Static', from Predator's Gold by Phillip Reeve

- The film Far North (2007), directed by Asif Kapadia from a short story by Sara Maitland, was filmed at Spitsbergen.[23].

See also

- Polish Polar Station, Hornsund - Hornsund fjord, operated since 1957

- Russenorsk language

- List of islands of Norway by area

- Vnukovo Airlines Flight 2801 - worst Norwegian air accident

Sources

- West Spitsbergen. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 16, 2005, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service.

References and notes

- ↑ Areas are taken from the Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1986. ISBN none. Various references provide slight differences in values.

- ↑ Fotherby, (1613) P45 re-published by Haven, S (1860).

- ↑ "Spitsbergen is the only correct spelling; Spitzbergen is a relatively modern blunder. The name is Dutch, not German. The second S asserts and commemorates the nationality of the discoverer." – Sir Martin Conway, No Man’s Land, 1906.

- ↑ Lockyer, N The Conway expedition to Spitzbergen Nature (1896)

- ↑ British documents onforeign affairs British Foreign Office (1908)

- ↑ TIME magazine NORWAY: Formal Annexation

- ↑ Hansard (1977)

- ↑ Hudson, Henry; Georg Michael Asher (1860). Henry Hudson the Navigator: The Original Documents in which His Career is Recorded, Collected, Partly Translated, and Annotated. London: Hakluyt Society. pp. clix-clx.

- ↑ Schokkenbroek, Joost C.A. (2008). Trying-out: An anatomy of Dutch Whaling and Sealing in the Nineteenth Century, 1815-1885. p. 27.

- ↑ pp.1-22. Georg Michael Asher,(1860). Henry Hudson the Navigator. Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, 27. ISBN 1402195583.

- ↑ William Martin Conway, (1906). No Man's Land: A History of Spitsbergen from Its Discovery in 1596 to the Beginning of the Scientific Exploration of the Country. Cambridge, At the University Press.

- ↑ Schokkenbroek, p. 28.

- ↑ pp. 18-20 in Már Jónsson. Denmark-Norway as a Potential World Power in the Early Seventeenth Century. Itinerario, Volume 33, Issue 02, July 2009, pp 17-27.

- ↑ Már Jónsson (2009) passim.,

- ↑ Pernille Ipsen and Gunlög Fur. Introduction to Scandinavian Colonialism. Itinerario, Volume 33, Issue 02, July 2009, pp 7-16.

- ↑ Northern Townships: Spitsbergen - article published in hidden europe magazine, 10 (September 2006), pp.2-5

- ↑ Operation article at lonesentry.com

- ↑ Sizilien article at www.bismarck-class.dk

- ↑ Oysten Wiig and Kjell Isaksen Seasonal Distribution of Harbour Seals, Bearded Seals, White Whales and Polar Bears in the Barents Sea

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, Globaltwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

- ↑ Norway Reveals Design of Doomsday' Seed Vault; Nature; Volume 445; 15 February 2007 BBC News; Work starts on Arctic seed vault, CNN

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "From Arctic Soil, Fossils of a Goliath That Ruled the Jurassic Seas". 2009-03-17. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/17/science/17foss.html.

- ↑ http://www.eyeforfilm.co.uk/feature.php?id=455 retrieved 14/12/2008

External links

- Photoseries from Dutch travel photographer Thijs Heslenfeld

- The Svalbard Pages

- General information on Spitsbergen

- Spitsbergen (photos, geographical and practical information, traveling reports and literature)

- Information on the nature of Spitsbergen, with many pictures

- Spitsbergen Maps

- Stone circles explained, with pictures of stones in Kvadehuksletta

- Spitsbergen Banknotes

- Captioned photos from Spitsbergen's Longyearbyen and Pyramiden

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||