Thermometer

A thermometer (from the Greek θερμός (thermo) meaning "warm" and meter, "to measure") is a device that measures temperature or temperature gradient using a variety of different principles. A thermometer has two important elements: the temperature sensor (e.g. the bulb on a mercury thermometer) in which some physical change occurs with temperature, plus some means of converting this physical change into a value (e.g. the scale on a mercury thermometer). Thermometers increasingly use electronic means to provide a digital display or input to a computer.

Contents |

Primary and secondary thermometers

Thermometers can be divided into two separate groups according to the level of knowledge about the physical basis of the underlying thermodynamic laws and quantities. For primary thermometers the measured property of matter is known so well that temperature can be calculated without any unknown quantities. Examples of these are thermometers based on the equation of state of a gas, on the velocity of sound in a gas, on the thermal noise (see Johnson–Nyquist noise) voltage or current of an electrical resistor, and on the angular anisotropy of gamma ray emission of certain radioactive nuclei in a magnetic field. Primary thermometers are relatively complex.

Secondary thermometers are most widely used because of their convenience. Also, they are often much more sensitive than primary ones. For secondary thermometers knowledge of the measured property is not sufficient to allow direct calculation of temperature. They have to be calibrated against a primary thermometer at least at one temperature or at a number of fixed temperatures. Such fixed points, for example, triple points and superconducting transitions, occur reproducibly at the same temperature.

Temperature

While an individual thermometer can measure degrees of hotness, the readings on two thermometers cannot be compared unless they conform to an agreed scale. There is today an absolute thermodynamic temperature scale. Internationally agreed temperature scales are designed to approximate this closely, based on fixed points and interpolating thermometers. The most recent official temperature scale is the International Temperature Scale of 1990. It extends from 0.65 K (−272.5 °C; −458.5 °F) to approximately 1,358 K (1,085 °C; 1,985 °F).

Early history

Various authors have credited the invention of the thermometer to Cornelius Drebbel, Robert Fludd, Galileo Galilei or Santorio Santorio. The thermometer was not a single invention, however, but a development.

Philo of Byzantium and Hero of Alexandria knew of the principle that certain substances, notably air, expand and contract and described a demonstration in which a closed tube partially filled with air had its end in a container of water.[1] The expansion and contraction of the air caused the position of the water/air interface to move along the tube.

Such a mechanism was later used to show the hotness and coldness of the air with a tube in which the water level is controlled by the expansion and contraction of the air. These devices were developed by several European scientists in the 16th and 17th centuries, notably Galileo Galilei.[2]. As a result, devices were shown to produce this effect reliably, and the term thermoscope was adopted because it reflected the changes in sensible heat (the concept of temperature was yet to arise).[2] The difference between a thermoscope and a thermometer is that the latter has a scale.[3] Though Galileo is often said to be the inventor of the thermometer, what he produced were thermoscopes.

Galileo also discovered that objects (glass spheres filled with aqueous alcohol) of slightly different densities would rise and fall, which is nowadays the principle of the Galileo thermometer (shown). Today such thermometers are calibrated to a temperature scale.

The first clear diagram of a thermoscope was published in 1617 by Giuseppe Biancani: the first showing a scale and thus constituting a thermometer was by Robert Fludd in 1638. This was a vertical tube, with a bulb at the top and the end immersed in water. The water level in the tube is controlled by the expansion and contraction of the air, so it is what we would now call an air thermometer.[4]

The first person to put a scale on a thermoscope is variously said to be Francesco Sagredo[5] or Santorio Santorio[6] in about 1611 to 1613.

The word thermometer (in its French form) first appeared in 1624 in La Récréation Mathématique by J. Leurechon, who describes one with a scale of 8 degrees.[7]

The above instruments suffered from the disadvantage that they were also barometers, i.e. sensitive to air pressure. In about 1654 Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, made sealed tubes part filled with alcohol, with a bulb and stem, the first modern-style thermometer, depending on the expansion of a liquid, and independent of air pressure.[7] Many other scientists experimented with various liquids and designs of thermometer.

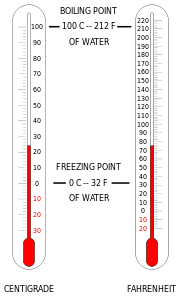

However, each inventor and each thermometer was unique—there was no standard scale. In 1665 Christiaan Huygens suggested using the melting and boiling points of water as standards, and in 1694 Carlo Renaldini proposed using them as fixed points on a universal scale. In 1701 Isaac Newton proposed a scale of 12 degrees between the melting point of ice and body temperature. Finally in 1724 Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit produced a temperature scale which now (slightly adjusted) bears his name. He could do this because he manufactured thermometers, using mercury (which has a high coefficient of expansion) for the first time and the quality of his production could provide a finer scale and greater reproducibility, leading to its general adoption. In 1742 Anders Celsius proposed a scale with zero at the boiling point and 100 degrees at the melting point of water,[8] though the scale which now bears his name has them the other way around.[9]

In 1866 Sir Thomas Clifford Allbutt invented a clinical thermometer that produced a body temperature reading in five minutes as opposed to twenty.[10] In 1999 Dr. Francesco Pompei of the Exergen Corporation introduced the world's first temporal artery thermometer, a non-invasive temperature sensor which scans the forehead in about 2 seconds and provides a medically accurate body temperature.[11][12]

Calibration

Thermometers can be calibrated either by comparing them with other calibrated thermometers or by checking them against known fixed points on the temperature scale. The best known of these fixed points are the melting and boiling points of pure water. (Note that the boiling point of water varies with pressure, so this must be controlled.)

The traditional method of putting a scale on a liquid-in-glass or liquid-in-metal thermometer was in three stages:

- Immerse the sensing portion in a stirred mixture of pure ice and water at 1 Standard atmosphere (101.325 kPa ; 760.0 mmHg) and mark the point indicated when it had come to thermal equilibrium.

- Immerse the sensing portion in a steam bath at 1 Standard atmosphere (101.325 kPa ; 760.0 mmHg) and again mark the point indicated.

- Divide the distance between these marks into equal portions according to the temperature scale being used.

Other fixed points were used in the past are the body temperature (of a healthy adult male) which was originally used by Fahrenheit as his upper fixed point (96 °F (36 °C) to be a number divisible by 12) and the lowest temperature given by a mixture of salt and ice, which was originally the definition of 0 °F (−18 °C).[13] (This is an example of a Frigorific mixture). As body temperature varies, the Fahrenheit scale was later changed to use an upper fixed point of boiling water at 212 °F (100 °C).[14]

These have now been replaced by the defining points in the International Temperature Scale of 1990, though in practice the melting point of water is more commonly used than its triple point, the latter being more difficult to manage and thus restricted to critical standard measurement. Nowadays manufacturers will often use a thermostat bath or solid block where the temperature is held constant relative to a calibrated thermometer. Other thermometers to be calibrated are put into the same bath or block and allowed to come to equilibrium, then the scale marked, or any deviation from the instrument scale recorded.[15] For many modern devices calibration will be stating some value to be used in processing an electronic signal to convert it to a temperature.

Precision, accuracy, and reproducibility

The precision or resolution of a thermometer is simply to what fraction of a degree it is possible to make a reading. For high temperature work it may only be possible to measure to the nearest 10°C or more. Clinical thermometers and many electronic thermometers are usually readable to 0.1°C. Special instruments can give readings to one thousandth of a degree. However, this precision does not mean the reading is true.

Thermometers which are calibrated to known fixed points (e.g. 0 and 100°C) will be accurate (i.e. will give a true reading) at that point. Most thermometers are originally calibrated to a constant-volume gas thermometer. In between a process of interpolation is used, generally a linear one.[15] This may give significant differences between different types of thermometer at points far away from the fixed points. For example the expansion of mercury in a glass thermometer is slightly different from the change in resistance of a platinum resistance of the thermometer, so these will disagree slightly at around 50°C.[16] There may be other causes due to imperfections in the instrument, e.g. in a liquid-in-glass thermometer if the capillary varies in diameter.[16]

For many purposes reproducibility is important. That is, does the same thermometer give the same reading for the same temperature (or do replacement or multiple thermometers give the same reading)? Reproducible temperature measurement means that comparisons are valid in scientific experiments and industrial processes are consistent. Thus if the same type of thermometer is calibrated in the same way its readings will be valid even if it is slightly inaccurate compared to the absolute scale.

An example of a reference thermometer used to check others to industrial standards would be a platinum resistance thermometer with a digital display to 0.1°C (its precision) which has been calibrated at 5 points against national standards (-18, 0, 40, 70, 100°C) and which is certified to an accuracy of ±0.2°C.[17]

According to a British Standard, correctly calibrated, used and maintained liquid-in-glass thermometers can achieve a measurement uncertainty of ±0.01°C in the range 0 to 100°C, and a larger uncertainty outside this range: ±0.05°C up to 200 or down to -40°C, ±0.2°C up to 450 or down to -80°C.[18]

Uses

There are a number of uses for thermometers. Thermometers have been built which utilize a range of physical effects to measure temperature. Temperature sensors are used in a wide variety of scientific and engineering applications, especially measurement systems. Temperature systems are primarily either electrical or mechanical, occasionally inseparable from the system which they control (as in the case of a mercury thermometer). Alcohol thermometers, infrared thermometers, mercury-in-glass thermometers, recording thermometers, thermistors, and Six's thermometers are used outside in areas which are well-exposed to the elements at various levels of the Earth's atmosphere and within the Earth's oceans is necessary within the fields of meteorology and climatology. Airplanes use thermometers and hygrometers to determine if atmospheric icing conditions exist along their flight path, and these measurements are used to initialize weather forecast models. Thermometers are used within roadways in cold weather climates to help determine if icing conditions exist. Indoors, thermistors are used in climate control systems such as air conditioners, freezers, heaters, refrigerators, and water heaters.[19] Galileo thermometers are used to measure indoor air temperature, due to their limited measurement range.

Bi-metallic stemmed thermometers, thermocouples, infrared thermometers, and thermisters are handy during cooking in order to know if meat has been properly cooked. Temperature of food is important because if it sits within environments with a temperature between 5 °C (41 °F) and 57 °C (135 °F) for four hours or more, bacteria can multiply leading to foodborne illnesses.[19] Thermometers are used in the production of candy. Medical thermometers such as mercury-in-glass thermometers,[20] infrared thermometers,[21] pill thermometers, and liquid crystal thermometers are used within health care to determine if individuals have a fever or are hypothermic. Liquid crystal thermometers can also be used to measure the temperature of water in fish tanks. Fiber Bragg grating temperature sensors are used within nuclear power facilities to monitor reactor core temperatures and avoid the possibility of nuclear meltdowns.[22]

Other types of thermometers

- Beckmann differential thermometer

- Bi-metal mechanical thermometer

- Coulomb blockade thermometer

- Galileo thermometer

- Resistance thermometer

- Reversing thermometer

- Silicon bandgap temperature sensor

- Phosphor thermometry

See also

- Automated airport weather station

- Timeline of temperature and pressure measurement technology

- Temperature conversion

References

- ↑ T. D. McGee (1988) Principles and Methods of Temperature Measurement ISBN 0471627674

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 R. S Doak (2005) Galileo: astronomer and physicist ISBN 0756508134 p36

- ↑ T. D. McGee (1988) Principles and Methods of Temperature Measurement page 3, ISBN 0471627674

- ↑ T. D. McGee (1988) Principles and Methods of Temperature Measurement, pages 2-4 ISBN 0471627674

- ↑ J. E. Drinkwater (1832)Life of Galileo Galilei page 41

- ↑ The Galileo Project: Santorio Santorio

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 R. P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8 page 4

- ↑ R. P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8 page 6

- ↑ Linnaeus' thermometer

- ↑ Sir Thomas Clifford Allbutt, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ http://www.exergen.com/about.htm

- ↑ http://patents.justia.com/inventor/FRANCESCOPOMPEI.html

- ↑ R. P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8, page 5

- ↑ J. Lord (1994) Sizes ISBN 0 06 273228 5 page 293

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 R. P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8, chapter 11 "Calibration of Temperature Sensors"

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 T. Duncan (1973) Advanced Physics: Materials and Mechanics (John Murray, Lodon) ISBN 0 7195 2844 5

- ↑ Peak Sensors Reference Thermometer

- ↑ BS1041-2.1:1985 Temperature Measurement- Part 2: Expansion thermometers. Section 2.1 Guide to selection and use of liquid-in-glass thermometers

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Angela M. Fraser, Ph.D. (2006-04-24). "Food Safety: Thermometers". North Carolina State University. pp. 1–2. http://www.foodsafetysite.com/resources/pdfs/EnglishServSafe/ENGSection5.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ↑ S. T. Zengeya and I. Blumenthal (December 1996). "Modern electronic and chemical thermometers used in the axilla are inaccurate". European Journal of Pediatrics 155 (12): 1005–1008. doi:10.1007/BF02532519. ISSN 1432-1076. http://www.springerlink.com/content/e321364274471520/. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ↑ E. F. J. Ring (January 2007). "The historical development of temperature measurement in medicine". Infrared Physics & Technology 49 (3): 297–301. doi:10.1016/j.infrared.2006.06.029. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TJ9-4MC71WT-1&_user=10&_coverDate=01%2F31%2F2007&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1224134065&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=f3dc94acfa466afad39e45d2f66f084a. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ↑ Alberto Fernandez Fernandez , Ez Fern , Member Spie , Andrei I. Gusarov , Benoît Brichard , Serge Bodart , Koen Lammens , Francis Berghmans , Member Spie , Marc Decréton , Patrice Mégret , Michel Blondel , Alain Delchambre (2002). "Temperature Monitoring of Nuclear Reactor Cores with Multiplexed Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors". Pennsylvania State University. doi:10.1.1.59.1761. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.59.1761. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

References

- History Channel - Invention - Notable Modern Inventions and Discoveries

- About - Thermometer - Thermometers - Early History, Anders Celsius, Gabriel Fahrenheit and Thomson Kelvin.

- Thermometers and Thermometric Liquids - Mercury and Alcohol.

- The NIST Industrial Thermometer Calibration Laboratory

Further reading

- Middleton, W. E. K. (1966). A history of the thermometer and its use in meteorology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted ed. 2002, ISBN 0801871530.

- The NIST Industrial Thermometer Calibration Laboratory

External links

- History of Temperature and Thermometry

- The Chemical Educator, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2000) The Thermometer—From The Feeling To The Instrument

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||