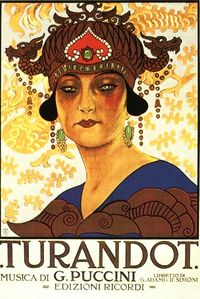

Turandot

| Giacomo Puccini |

|---|

|

|

Operas

|

Turandot (Italian pronunciation: [turan ˈdɔt]) is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini, set to a libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni. Though Puccini's first interest in the subject was based on his reading of Friedrich Schiller's[1] adaptation of the play, his work is most nearly based on the earlier text Turandot by Carlo Gozzi. Turandot was unfinished at the time of Puccini's death and was later completed by Franco Alfano. The first performance was held at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan on April 25, 1926 and conducted by Arturo Toscanini. This performance included only Puccini's music and not Alfano's additions. The first performance of the opera, as completed by Alfano, was conducted by Ettore Panizza.[2]

Contents |

Origin of the name

Turandot is a Persian word and name meaning "the daughter of Turan", Turan being a region of Central Asia which used to be part of the Persian Empire.

In Persian, the fairy tale is known as Turandokht, with "dokht" being a contraction for dokhtar (meaning daughter), and both the "kh" and "t" are clearly pronounced. However, according to Puccini scholar Patrick Vincent Casali, the final "t" should not be sounded in the pronunciation of the opera's name or when referring to the title character. Puccini never pronounced the final "t", according to soprano Rosa Raisa, who was the first singer to interpret the title role. Furthermore, Dame Eva Turner, the most renowned Turandot of the inter-war period, insisted on pronouncing the word as "Turan-do" (i.e. without the final "t"), as television interviews with her attest. As Casali notes, too, the musical setting of many of Calaf's utterances of the name makes sounding the final "t" all but impossible.[3] However Simonetta Puccini, Puccini's granddaughter and keeper of the Villa Puccini and Mausoleum, has stated that the final "t" must be pronounced.

Composition history

The story of Turandot was taken from a Persian collection of stories called The Book of One Thousand and One Days [4] or Hezar o-yek shab (1722 French translation Les Mille et un jours by François Petis de la Croix — not to be confused with its sister work The Book of One Thousand and One Nights), where the character of "Turandokht" as a cold Turk (Uygur) princess was found.[5] The story of Turandokht is one of the best known from de la Croix's translation. The plot respects the classical unities of time, space and action.

Puccini first began working on Turandot in March 1920 after meeting with librettists Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni. He began composition in January 1921. By March 1924 he had completed the opera up to the final duet. However, he was unsatisfied with the text of the final duet, and did not continue until October 8, when he chose Adami's fourth version of the duet text. On October 10 he was diagnosed with throat cancer and on November 24 went to Brussels, Belgium for treatment. There he underwent a new and experimental radiation therapy treatment. Puccini and his wife never knew how serious the cancer was, as the news was only revealed to his son. He died of complications on November 29, 1924.

He left behind 36 pages of sketches on 23 sheets for the end of Turandot, together with instructions that Riccardo Zandonai should finish the opera. Puccini's son Tonio objected, and eventually Franco Alfano was chosen to flesh out the sketches after Vincenzo Tommasini (who had completed Boito's Nerone after the composer’s death) and Pietro Mascagni were rejected. Puccini's editor Giovanni Ricordi decided on Alfano because his opera La leggenda di Sakùntala resembled Turandot in its setting and heavy orchestration.[2] Alfano provided a first version of the ending with a few passages of his own, and even a few sentences added to the libretto which was not considered complete even by Puccini himself. After the severe criticisms by Ricordi and the conductor Arturo Toscanini, he was forced to write a second, strictly censored version that followed Puccini's sketches more closely, to the point where he did not set some of Adami's text to music because Puccini had not indicated how he wanted it to sound. Ricordi's real concern was not the quality of Alfano's work, but that he wanted the end of Turandot to sound as if it had been written by Puccini, and Alfano's editing had to be seamless. Of this version, about three minutes were cut for performance by Toscanini and it is this shortened version that is usually performed.

The premiere of Turandot was at La Scala, Milan, on Sunday April 25, 1926, with Rosa Raisa in the title role one year and five months after Puccini's death. It was conducted by Arturo Toscanini. In the middle of Act III, two measures after the words "Liù, poesia!", the orchestra rested. Toscanini stopped and laid down his baton. He turned to the audience and announced: "Qui finisce l'opera, perché a questo punto il maestro è morto" ("Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died"). The curtain was lowered slowly. [6] Toscanini apparently never conducted the opera again.[2] The second and subsequent performances at the 1926 La Scala season were conducted by Ettore Panizza[2] and they included Alfano's ending. (As discussed in Ashbrook and Powers [7], the music for Liù's death was not in fact Puccini's final composition, but had been orchestrated some nine months earlier). Tenors Miguel Fleta and Franco Lo Giudice alternated in the role of Prince Calàf in the original production, although Fleta had the honor of singing the role for the opera's opening night.

Performance history

Turandot quickly spread to other venues: Rome (Teatro Costanzi, April 29, four days after the Milan premiere), Buenos Aires (Teatro Colón, June 23), Dresden (September 6, in German), Venice (La Fenice, September 9), Vienna (October 14; Mafalda Salvatini in the title role), Berlin (November 8), New York (Metropolitan Opera, November 16), Brussels (La Monnaie, 17 December, in French), Naples (Teatro San Carlo, January 17, 1927), Parma (February 12), Turin (March 17), London (Covent Garden, June 7), San Francisco (September 19), Bologna (October 1927), Paris (March 29, 1928), Moscow (Bolshoi Theatre, 1931).

Turandot is a staple of the standard operatic repertoire and it appears as number twelve on Opera America's list of the 20 most-performed operas in North America.[8]

For many years, the Government of the People's Republic of China forbade performance of Turandot because they said it portrayed China and the Chinese unfavourably. [9][10] In the late 1990s they relented, and in September 1998 the opera was performed for eight nights at the Forbidden City, complete with opulent sets and soldiers from the People's Liberation Army as extras. It was an international collaboration, with director Zhang Yimou as choreographer and Zubin Mehta as conductor. The singing roles saw Giovanna Casolla, Audrey Stottler, and Sharon Sweet as Princess Turandot; Sergej Larin and Lando Bartolini as Calàf; and Barbara Frittoli, Cristina Gallardo Domas, and Barbara Hendricks as Liù.

As with Madama Butterfly, Puccini strove for a semblance of Asian authenticity (at least to Western ears) by using music from the region in question. Up to eight of the themes used in Turandot appear to be based on traditional Chinese music, and the melody of a Chinese song named "Mò Li Hūa (茉莉花)", or "Jasmine", is included as a motif for the princess. [11]

Alfano's original ending

The debate over which version of the ending is better is still open,[7] but the consensus generally tends towards Alfano's first score. Scrutiny of the sketches, which Ricordi later allowed scholars to analyze (and sometimes publish), showed how Alfano actually did not even try to use most of the short sketches on the sheets, with the exception of those with an obvious placement and one short theme he freely transformed, and used for the sake of stylistic continuity. From 1976 to 1988 the American composer Janet Maguire, convinced that the whole ending is coded in the sketches left by Puccini, composed a new ending, but this has never been performed. In 2001 Luciano Berio made a new sanctioned completion, using Puccini's sketches but also expanding the musical language, but this has received a mixed reception.

The opera with Alfano's original ending has been recorded more than once. The first definitely known live performance of the opera with Alfano's original ending was not mounted until November 3, 1982, at the Barbican, London. It may have been staged in Germany in the early years, since Ricordi had commissioned a German translation of the text and a number of scores were printed in Germany with the full final scene included. This includes the aria "Del primo pianto", which is not usually performed. Recordings of this aria by the inter-war singers Anna Roselle and Lotte Lehmann exist, which suggests they may have sung the original ending on stage, but no other evidence is available.[2]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere Cast, April 25, 1926 (Conductor: Arturo Toscanini) |

|---|---|---|

| Princess Turandot | soprano | Rosa Raisa |

| The Emperor Altoum, her father | tenor | Francesco Dominici |

| Timur, the deposed King of Tartary | bass | Carlo Walter |

| The Unknown Prince (Calàf), his son | tenor | Miguel Fleta |

| Liù,[12] a slave girl | soprano | Maria Zamboni |

| Ping, Lord Chancellor | baritone | Giacomo Rimini |

| Pang, Majordomo | tenor | Emilio Venturini |

| Pong, Head chef of the Imperial Kitchen | tenor | Giuseppe Nessi |

| A Mandarin | baritone | Aristide Baracchi |

| The Prince of Persia | tenor | Not named in the original program |

| The Executioner (Pu-Tin-Pao) | silent | Not named in the original program |

| Imperial guards, the executioner's men, boys, priests, mandarins, dignitaries, eight wise men,Turandot's handmaids, soldiers, standard-bearers, musicians, ghosts of suitors, crowd | ||

Synopsis

- Place: Peking, China

- Time: Legendary times

Act 1

In front of the imperial palace

A Mandarin announces the law of the land (Popolo di Pechino! - "Any man who desires to wed Turandot must first answer her three riddles. If he fails, he will be beheaded"). The Prince of Persia has failed and is to be beheaded at moonrise. As the crowd surges towards the gates of the palace, the imperial guards brutally repulse them, a blind old man is pushed to the ground. His slave-girl, Liù, cries for help. A young man hears her cry and recognizes the old man as his long-lost father, Timur, the deposed king of Tartary. The young Prince of Tartary is overjoyed at seeing his father alive but urges him not to speak his name because he fears the Chinese rulers who have conquered Tartary. Timur tells his son that, of all his servants, only Liù has remained faithful to him. When the Prince asks her why, she tells him that once, long ago in the palace, he smiled upon her (The crowd, Liù, Prince of Tartary, Timur: Indietro, cani!).

The moon rises, and the crowd's cries for blood turn into silence. The doomed Prince of Persia is led before the crowd on his way to execution. The young Prince is so handsome that the crowd and the Prince of Tartary are moved to compassion and call on Turandot to spare his life (The crowd, Prince of Tartary: O giovinetto!). She appears, and with a single imperious gesture orders the execution to continue. The Prince of Tartary, who has never seen Turandot before, falls immediately in love. He cries out Turandot's name (three times) with joy, and the Prince of Persia echoes his final cry. The crowd screams in horror as the Prince of Persia is beheaded.

The Prince of Tartary is dazzled by Turandot's beauty. He is about to rush towards the gong and strike it three times— the symbolic gesture of whoever wishes to marry Turandot—when the ministers Ping, Pong, and Pang appear and urge him cynically (Fermo, che fai?) not to lose his head for Turandot but to go back to his own country. Timur urges his son to desist, and Liù, who is secretly in love with the Prince, pleads with him (Signore, ascolta! - "My lord, listen!") not to attempt the riddles. Liù's words touch his heart. The Prince tells Liù to make exile more bearable and never to abandon his father if the Prince fails to answer the riddles (Non piangere, Liù - "Don't cry, Liù"). The three ministers, Timur, and Liù try one last time to hold the Prince ( Ah! Per l'ultima volta! ) but he refuses to listen.

He calls Turandot's name three times, and each time Liù, Timur, and the ministers reply, "Death!", and the crowd declars "we're already digging your grave!" Rushing to the gong that hangs in front of the palace, he strikes it three times, declaring himself a suitor. From the palace balcony, Turandot accepts the challenge, as Ping, Pang and Pong laugh at the prince's foolishness.

Act 2

Scene 1: A pavilion in the imperial palace. Before sunrise

Ping, Pang, and Pong lament their place as ministers, poring over palace documents and presiding over endless rituals. They prepare themselves for either a wedding or a funeral (Ping, Pang, Pong: Ola, Pang!). Ping suddenly longs for his country house in Honan, with its small lake surrounded by bamboo. Pong remembers his grove of forests near Tsiang, and Pang recalls his gardens near Kiu. The three share fond memories of life away from the palace (Ping, Pang, Pong: Ho una casa nell'Honan) but are shaken back to the realities of Turandot's bloody reign. They continually accompany young men to death and recall their ghastly fate. As the palace trumpet sounds, the ministers ready themselves for another spectacle as they await the entrance of the Emperor.

Scene 2: The courtyard of the palace. Sunrise

The Emperor Altoum, father of Turandot, sits on his grand throne in his palace. He urges the Prince to withdraw his challenge but the Prince refuses (Altoum, the Prince: Un giuramento atroce). Turandot enters and explains (In questa reggia) that her ancestress of millennia past, Princess Lo-u-Ling, reigned over her kingdom "in silence and joy, resisting the harsh domination of men" until she was ravished and murdered by an invading foreign prince. Lo-u-Ling now lives again in Turandot and out of revenge she has sworn never to let any man possess her. She warns the Prince to withdraw, but again he refuses. The Princess presents her first riddle: Straniero, ascolta! - "... What is born each night and dies each dawn?" The Prince correctly replies, "Hope." The Princess, unnerved, presents her second riddle (Guizza al pari di fiamma - "What flickers red and warm like a flame, but is not fire?") The Prince thinks for a moment before replying, Sangue - "Blood". Turandot is shaken. The crowd cheers the Prince, provoking Turandot's anger. She presents her third riddle (Gelo che ti da foco - "What is like ice, but burns like fire?"). As the prince thinks, Turandot taunts him "what is the ice that makes you burn? The taunt makes him see the answer and proclaimes "It is Turandot!"

The crowd cheers for the triumphant Prince. Turandot throws herself at her father's feet and pleads with him not to leave her to the Prince's mercy. The Emperor insists that an oath is sacred, and it is Turandot's duty to wed the Prince (Turandot, Altoum, the Prince: Figlio del cielo). As she cries out in despair, the Prince stops her, saying that he has a proposal for her: Tre enigmi m'hai proposto - "You do not know my name. Bring me my name before sunrise, and at sunrise, I will die" Turandot accepts. The Emperor declares that he hopes to call the Prince his son come sunrise.

Act 3

Scene 1: The palace gardens. Night

In the distance, heralds call out Turandot's command: Cosi comanda Turandot - "This night, none shall sleep in Peking! The penalty for all will be death if the Prince's name is not discovered by morning". The Prince waits for dawn and anticipates his victory: Nessun dorma - "Nobody shall sleep!... Nobody shall sleep! Even you, O Princess"

Ping, Pong, and Pang appear and offer the Prince women and riches if he will only give up Turandot (Tu che guardi le stelle), but he refuses. A group of soldiers then drag in Timur and Liù. They have been seen speaking to the Prince, so they must know his name. Turandot enters and orders Timur and Liù to speak. The Prince feigns ignorance, saying they know nothing. Liù declares that she alone knows the Prince's name, but she will not reveal it. Ping demands the Prince's name, and when she refuses, she is tortured. Turandot is clearly taken by Liù's resolve and asks her who put so much strength in her heart. Liù answers "Princess, Love!". Turandot demands that Ping tear the Prince's name from Liù, and he orders her to be tortured further. Liù counters Turandot (Tu che di gel sei cinta - "You who are begirdled by ice"), saying that she too shall learn love. Having spoken, Liù seizes a dagger from a soldier's belt and stabs herself. As she staggers towards the Prince and falls dead, the crowd screams for her to speak the Prince's name. Since Timur is blind, he must be told about Liù's death, and he cries out in anguish. Timur warns that the gods will be offended by this outrage, and the crowd is subdued with shame and fear. The grieving Timur and the crowd follow Liù's body as it is carried away. Everybody departs leaving the Prince and Turandot. He reproaches Turandot for her cruelty (The Prince, Turandot: Principessa di morte - "Princess of death") and then takes her in his arms and kisses her in spite of her resistance. Here Puccini's work ends. The remainder of the music was completed by Franco Alfano.[13]

The Prince tries to convince Turandot to love him. At first she is disgusted, but after he kisses her, she feels herself turning towards passion. She asks him to ask for nothing more and to leave, taking his mystery with him. The Prince however, reveals his name, "Calàf, son of Timur" and places his life in Turandot's hands. She can now destroy him if she wants (Turandot, Calàf: Del primo pianto).

Scene 2: The courtyard of the palace. Dawn

Turandot and Calàf approach the Emperor's throne. She declares that she knows the Prince's name: Diecimila anni al nostro Imperatore! - "It is ... love!" The crowd cheers and acclaims the two lovers (O sole! Vita! Eternità).

Critical response

Whilst long recognised as the most tonally adventurous of Puccini's operas,[14] Turandot has also been considered a flawed masterpiece, and some critics have been unreservedly hostile. Joseph Kerman states:

- "Nobody would deny that dramatic potential can be found in this tale. Puccini, however, did not find it; his music does nothing to rationalize the legend or illuminate the characters."[15]

Kerman also wrote that while Turandot is more "suave" musically than Puccini's earlier opera, Tosca, "dramatically it is a good deal more depraved."[16] Some of this criticism is possibly due to the standard Alfano ending (Alfano II), in which Liù's death is followed almost immediately by Calaf's 'rough wooing' of Turandot, and the 'bombastic' end to the opera. The Berio version is considered to overcome some of these criticisms, but critics such as Michael Tanner have failed to be wholly convinced by the new ending, noting that the criticism by the Puccini advocate Julian Budden still applies:

- "Nothing in the text of the final duet suggests that Calaf's love for Turandot amounts to anything more than a physical obsession: nor can the ingenuities of Simoni and Adami's text for 'Del primo pianto' convince us that the Princess's submission is any less hormonal."[17]

Ashbrook and Powers[7] consider it was an awareness of this problem — an inadequate buildup for Turandot's change of heart, combined with an overly successful treatment of the secondary character (Liù) — which contributed to Puccini's inability to complete the opera.

Concerning the compelling believability of the self-sacrificial Liù character in contrast to the two mythic protagonists, biographers note echoes in Puccini's own life. He had had a servant named Doria, whom his wife accused of sexual relations with Puccini. The accusations escalated until Doria killed herself — though the autopsy revealed she died a virgin. In Turandot, Puccini lavished his attention on the familiar sufferings of Liù, as he had on his many previous suffering heroines. However, in the opinion of Father Owen Lee, Puccini was out of his element when it came to resolving the tale of his two allegorical protagonists: Finding himself completely outside his normal genre of verismo, he was incapable of completely grasping and resolving the necessary elements of the mythic, unable to "feel his way into the new, forbidding areas the myth opened up to him"[18] — and thus unable to finish the opera in the two years before his unexpected death.

Instrumentation

Turandot is scored for the following large orchestra:

- woodwinds: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets in B-flat, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 onstage Alto saxophones in E-flat

- brass: 4 horns in F, 3 trumpets in F, 3 trombones, contrabass trombone, 6 onstage trumpets in B-flat, 3 onstage trombones, onstage bass trombone

- percussion: timpani, cymbals, gong, triangle, snare drum, bass drum, tam-tam, glockenspiel, xylophone, bass xylophone, tubular bells, tuned Chinese gongs[19], onstage wood block, onstage large gong

Recordings

References

- ↑ List of Friedrich Schiller's works

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Turandot: Concert Opera Boston

- ↑ For a discussion about the pronunciation of the name, cf. Patrick Vincent Casali (1997). "The Pronunciation of Turandot: Puccini's Last Enigma". Opera Quarterly 13 (4): 77–91. ISSN 0736-0053 / Online ISSN 1476-2870. http://oq.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/13/4/77/.

- ↑ based on a story by the Persian poet Nizemi

- ↑ Turandot, Princess of China

- ↑ These are the words reported by Eugenio Gara, who was present at the prima, in

- a cura di Eugenio Gara. (1958). Carteggi Pucciniani. edited by Eugenio Gara. Milan: Ricordi. ISBN 88-7592-134-2.

- William Ashbrook (1984). "Turandot and Its Posthumous Prima". Opera Quarterly 2 (3): 126–132. doi:10.1093/oq/2.3.126. ISSN 0736-0053 / Online ISSN 1476-2870. http://oq.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/2/3/126.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ashbrook, W. and Powers, H. "Puccini's Turandot: The End of the Great Tradition". Princeton University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-691-02712-9

- ↑ ""Top 20 list of most-performed operas". Opera America. Retrieved on September 28, 2008.

- ↑ Banned in China

- ↑ Banned in China because officials believed it portrays the country negatively

- ↑ See above, "Ashbrook and Powers, Chapter 4"

- ↑ Note that the grave accent (`) in the name Liù is not a pinyin tone mark indicating a falling tone, but an Italian diacritic that marks stress, indicating that the word is pronounced [ˈlju] rather than [ˈli.u]. If the name is analyzed as an authentic Mandarin-language name, it likely to be one of the several characters pronounced Liu (with different respective tones) that are commonly used as surnames: 刘 Liú [ljôu] or 柳 Liǔ [ljòu].

- ↑ A later attempt at completing the opera was made, with the co-operation of the publishers, Ricordi, in 2002 by Luciano Berio

- ↑ Jonathan Christian Petty and Marshall Tuttle, "Tonal Psychology in Puccini's Turandot ", Center for Korean Studies, University of California, Berkeley and Langston University, 2001

- ↑ Joseph Kerman, Opera As Drama, New York: Knopf, 1956 (revised edition, p. 206. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988, ISBN 0-520-06274-4)

- ↑ Joseph Kerman, Opera As Drama, New York: Knopf, 1956 (revised edition, p. 205)

- ↑ Tanner, Michael. "Hollow swan-song". The Spectator, March 22, 2003.

- ↑ Lee, Father Owen. "Turandot: Father Owen Lee Discusses Puccini's Turandot." Metropolitan Opera Radio Broadcast Intermission Feature, March 4, 1961.

- ↑ Blades, James, Percussion instruments and their history, Bold Strummer, 1992, p. 344. ISBN 0-933224-61-3

External links

- Analysis and Background

- Story, Music, Background, Puccini Biography, Photos, etc. – Metropolitan Opera International Radio Broadcast Information Center

- Musical and Dramatic Analysis – by Boris Goldovsky

- Libretto, Discography, and Listenable Media

- Complete libretto with translations – from Opera Today

- Recordings of Turandot

- Tu che di gel sei cinta – Liù's aria (recording by Jana Lady Lou)