Amharic language

| Amharic | ||

|---|---|---|

| አማርኛ amarəñña | ||

| Pronunciation | [amarɨɲɲa] | |

| Spoken in | ||

| Total speakers | 25,000,000+ total, 15,000,000+ monolinguals (1998) | |

| Language family | Afro-Asiatic

|

|

| Writing system | Ge'ez alphabet abugida | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | Ethiopia and the following specific regions: Addis Ababa City Council, Amhara Region, Benishangul-Gumuz Region, Dire Dawa Administrative council, Gambela Region, SNNPR | |

| Regulated by | no official regulation | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | am | |

| ISO 639-2 | amh | |

| ISO 639-3 | amh | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Amharic (Amharic: አማርኛ? amarəñña) is a Semitic language spoken in North Central Ethiopia by the Amhara. It is the second most-spoken Semitic language in the world, after Arabic, and the official working language of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Thus, it has official status and is used nationwide. Amharic is also the official or working language of several of the states within the federal system, including the Amhara Region and the multi-ethnic Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region, among others. It has been the working language of government, the military, and of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church throughout medieval and modern times. Outside Ethiopia, Amharic is the language of some 2.7 million emigrants (notably in Egypt, Israel, and Sweden).

It is written using Amharic Fidel, ፊደል, which grew out of the Ge'ez abugida—called, in Ethiopian Semitic languages, ፊደል fidel ("alphabet", "letter," or "character") and አቡጊዳ abugida (from the first four Ethiopic letters which gave rise to the modern linguistic term abugida).

Contents |

Sounds and orthography

Consonant and vowel phonemes

There is no agreed way of transliterating Amharic into Roman characters. The Amharic examples in the sections below use one system that is common, though not universal, among linguists specializing in Ethiopian Semitic languages. The Amharic ejectives correspond to the Proto-Semitic "emphatic consonants", usually transcribed with a dot below the letter. The consonant and vowel charts give these symbols in parentheses where they differ from the standard IPA symbols.

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ (ñ) | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | ʔ (ʾ) | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| ejective | pʼ (p', p̣) | tʼ (t', ṭ) | kʼ (q, ḳ) | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | tʃ (č) | ||||

| voiced | dʒ (ǧ) | |||||

| ejective | tsʼ (s') | tʃʼ (č', č̣) | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ (š) | h | |

| voiced | z | ʒ (ž) | ||||

| Approximant | l | j (y) | w | |||

| Rhotic | r | |||||

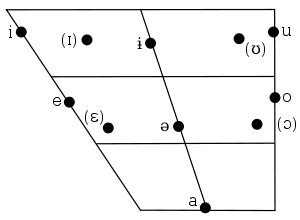

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | ɨ (ə) | u |

| Mid | e | ə (ä) | o |

| Low | a |

Fidel signs

The following chart represents the basic forms of the consonants, ignoring the so-called "bastard" (Amh. ዲቃላ dīḳālā) labiovelarized forms of each consonant (represented by the addition of a superscripted "w," i.e. "ʷ") and not including the wholly labiovelarized consonants ḳʷ, hʷ (Ge'ez ḫʷ), kʷ, and gʷ. Some phonemes can be represented by more than one series of symbols: /'/, /s'/, and /h/ (the last has four distinct letter forms). The citation form for each series is the consonant+/ä/ form, i.e. the first column of fidel. You will need a font that supports Ethiopic, such as GF Zemen Unicode, in order to view the fidel.

Non-speakers are often disconcerted or astonished by the remarkable similarity of many of the symbols. This is mitigated somewhat because, like many Semitic languages, Amharic uses triconsonantal roots in its verb morphology. The result of this is that a fluent speaker of Amharic can often decipher written text by observing the consonants, with the vowel variants being supplemental detail.

| ä | u | i | a | e | ə | o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | ሀ | ሁ | ሂ | ሃ | ሄ | ህ | ሆ |

| l | ለ | ሉ | ሊ | ላ | ሌ | ል | ሎ |

| h | ሐ | ሑ | ሒ | ሓ | ሔ | ሕ | ሖ |

| m | መ | ሙ | ሚ | ማ | ሜ | ም | ሞ |

| s | ሠ | ሡ | ሢ | ሣ | ሤ | ሥ | ሦ |

| r | ረ | ሩ | ሪ | ራ | ሬ | ር | ሮ |

| s | ሰ | ሱ | ሲ | ሳ | ሴ | ስ | ሶ |

| š | ሸ | ሹ | ሺ | ሻ | ሼ | ሽ | ሾ |

| q | ቀ | ቁ | ቂ | ቃ | ቄ | ቅ | ቆ |

| b | በ | ቡ | ቢ | ባ | ቤ | ብ | ቦ |

| t | ተ | ቱ | ቲ | ታ | ቴ | ት | ቶ |

| č | ቸ | ቹ | ቺ | ቻ | ቼ | ች | ቾ |

| h | ኀ | ኁ | ኂ | ኃ | ኄ | ኅ | ኆ |

| n | ነ | ኑ | ኒ | ና | ኔ | ን | ኖ |

| ñ | ኘ | ኙ | ኚ | ኛ | ኜ | ኝ | ኞ |

| ʾ | አ | ኡ | ኢ | ኣ | ኤ | እ | ኦ |

| k | ከ | ኩ | ኪ | ካ | ኬ | ክ | ኮ |

| h | ኸ | ኹ | ኺ | ኻ | ኼ | ኽ | ኾ |

| w | ወ | ዉ | ዊ | ዋ | ዌ | ው | ዎ |

| ʾ | ዐ | ዑ | ዒ | ዓ | ዔ | ዕ | ዖ |

| z | ዘ | ዙ | ዚ | ዛ | ዜ | ዝ | ዞ |

| ž | ዠ | ዡ | ዢ | ዣ | ዤ | ዥ | ዦ |

| y | የ | ዩ | ዪ | ያ | ዬ | ይ | ዮ |

| d | ደ | ዱ | ዲ | ዳ | ዴ | ድ | ዶ |

| ǧ | ጀ | ጁ | ጂ | ጃ | ጄ | ጅ | ጆ |

| g | ገ | ጉ | ጊ | ጋ | ጌ | ግ | ጎ |

| t' | ጠ | ጡ | ጢ | ጣ | ጤ | ጥ | ጦ |

| č' | ጨ | ጩ | ጪ | ጫ | ጬ | ጭ | ጮ |

| p' | ጰ | ጱ | ጲ | ጳ | ጴ | ጵ | ጶ |

| s' | ጸ | ጹ | ጺ | ጻ | ጼ | ጽ | ጾ |

| s' | ፀ | ፁ | ፂ | ፃ | ፄ | ፅ | ፆ |

| f | ፈ | ፉ | ፊ | ፋ | ፌ | ፍ | ፎ |

| p | ፐ | ፑ | ፒ | ፓ | ፔ | ፕ | ፖ |

Gemination

As in most other Ethiopian Semitic languages, gemination is contrastive in Amharic. That is, consonant length can distinguish words from one another; for example, alä 'he said', allä 'there is'; yǝmätall 'he hits', yǝmmättall 'he is hit'. Gemination is not indicated in Amharic orthography, but Amharic readers seem not to find this to be a problem. This property of the writing system is analogous to the vowels of Arabic and Hebrew or the tones of many Bantu languages, which are not normally indicated in writing. The noted Ethiopian novelist Haddis Alemayehu, who was an advocate of Amharic orthography reform, indicated gemination in his novel Fǝqǝr Ǝskä Mäqabǝr by placing a dot above the characters whose consonants were geminated, but this practice has not caught on.

Grammar

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

In most languages, there is a small number of basic distinctions of person, number, and often gender that play a role within the grammar of the language. We see these distinctions within the basic set of independent personal pronouns, for example, English I, Amharic እኔ ǝne; English she, Amharic እሷ ǝsswa. In Amharic, as in other Semitic languages, the same distinctions appear in three other places within the grammar of the languages.

- Subject-verb agreement

- All Amharic verbs agree with their subjects; that is, the person, number, and (2nd and 3rd person singular) gender of the subject of the verb are marked by suffixes or prefixes on the verb. Because the affixes that signal subject agreement vary greatly with the particular verb tense/aspect/mood, they are normally not considered to be pronouns and are discussed elsewhere in this article under verb conjugation.

- Object pronoun suffixes

- Amharic verbs often have additional morphology that indicates the person, number, and (2nd and 3rd person singular) gender of the object of the verb.

-

አልማዝን አየኋት almazǝn ayyähʷ-at Almaz-ACC I-saw-her 'I saw Almaz'

- While morphemes such as -at in this example are sometimes described as signaling object agreement, analogous to subject agreement, they are more often thought of as object pronoun suffixes because, unlike the markers of subject agreement, they do not vary significantly with the tense/aspect/mood of the verb. For arguments of the verb other than the subject or the object, there are two separate sets of related suffixes, one with a benefactive meaning ('to', 'for'), the other with an adversative or locative meaning ('against', 'to the detriment of', 'on', 'at').

-

ለአልማዝ በሩን ከፈትኩላት lä’almaz bärrun käffätku-llat for-Almaz door-DEF-ACC I-opened-for-her 'I opened the door for Almaz'

-

በአልማዝ በሩን ዘጋሁባት bä’almaz bärrun zäggahu-bbat on-Almaz door-DEF-ACC I-closed-on-her 'I closed the door on Almaz (to her detriment)'

- Morphemes such as -llat and -bbat in these examples will be referred to in this article as prepositional object pronoun suffixes because they correspond to prepositional phrases such as 'for her' and 'on her', to distinguish them from the direct object pronoun suffixes such as -at 'her'.

- Possessive suffixes

- Amharic has a further set of morphemes which are suffixed to nouns, signalling possession: ቤት bet 'house', ቤቴ bete 'my house', ቤቷ betwa 'her house'.

In each of these four aspects of the grammar, independent pronouns, subject-verb agreement, object pronoun suffixes, and possessive suffixes, Amharic distinguishes eight combinations of person, number, and gender. For first person, there is a two-way distinction between singular ('I') and plural ('we'), whereas for second and third persons, there is a distinction between singular and plural and within the singular a further distinction between masculine and feminine ('you m. sg.', 'you f. sg.', 'you pl.', 'he', 'she', 'they').

Like other Semitic languages, Amharic is a pro-drop language. That is, neutral sentences in which no element is emphasized normally do not have independent pronouns: ኢትዮጵያዊ ነው ityop'p'ǝyawi näw 'he's Ethiopian,' ጋበዝኳት ‘gabbäzkwat 'I invited her'. The Amharic words that translate 'he', 'I', and 'her' do not appear in these sentences as independent words. However, in such cases, the person, number, and (2nd or 3rd person singular) gender of the subject and object are marked on the verb. When the subject or object in such sentences is emphasized, an independent pronoun is used: እሱ ኢትዮጵያዊ ነው ǝssu ityop'p'ǝyawi näw 'he's Ethiopian', እኔ ጋበዝኳት ǝne gabbäzkwat 'I invited her', እሷን ጋበዝኳት ǝsswan gabbäzkwat 'I invited her'.

The table below shows alternatives for many of the forms. The choice depends on what precedes the form in question, usually whether this is a vowel or a consonant, for example, for the 1st person singular possessive suffix, አገሬ agär-e 'my country', ገላዬ gäla-ye 'my body'.

| English | Independent | Object pronoun suffixes | Possessive suffixes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Prepositional | ||||

| Benefactive | Locative/Adversative | ||||

| I | እኔ ǝne |

-(ä/ǝ)ñ | -(ǝ)llǝñ | -(ǝ)bbǝñ | -(y)e |

| you (m. sg.) | አንተ antä |

-(ǝ)h | -(ǝ)llǝh | -(ǝ)bbǝh | -(ǝ)h |

| you (f. sg.) | አንቺ anči |

-(ǝ)š | -(ǝ)llǝš | -(ǝ)bbǝš | -(ǝ)š |

| he | እሱ ǝssu |

-(ä)w, -t | -(ǝ)llät | -(ǝ)bbät | -(w)u |

| she | እሷ ǝsswa |

-at | -(ǝ)llat | -(ǝ)bbat | -wa |

| we | እኛ ǝñña |

-(ä/ǝ)n | -(ǝ)llǝn | -(ǝ)bbǝn | -aččǝn |

| you (pl.) | እናንተ ǝnnantä |

-aččǝhu | -(ǝ)llaččǝhu | -(ǝ)bbaččǝhu | -aččǝhu |

| they | እነሱ ǝnnässu |

-aččäw | -(ǝ)llaččäw | -(ǝ)bbaččäw | -aččäw |

Within second and third person singular, there are two additional "polite" independent pronouns, for reference to people that the speaker wishes to show respect towards. This usage is an example of the so-called T-V distinction that is made in many languages. The polite pronouns in Amharic are እርስዎ ǝrswo 'you sg. pol.' and እሳቸው ǝssaččäw 'he/she pol.'. Although these forms are singular semantically — they refer to one person — they correspond to 3rd person plural elsewhere in the grammar, as is common in other T-V systems. For the possessive pronouns, however, the polite 2nd person has the special suffix -wo 'your sg. pol.'.

For possessive pronouns ('mine', 'yours', etc.), Amharic adds the independent pronouns to the preposition yä- 'of': የኔ yäne 'mine', ያንተ yantä 'yours m. sg.', ያንቺ yanči 'yours f. sg.', የሷ yässwa 'hers', etc.

Reflexive pronouns

For reflexive pronouns ('myself', 'yourself', etc.), Amharic adds the possessive suffixes to the noun ራስ ras 'head': ራሴ rase 'myself', ራሷ raswa 'herself', etc.

Demonstrative pronouns

Like English, Amharic makes a two-way distinction between near ('this, these') and far ('that, those') demonstrative expressions (pronouns, adjectives, adverbs). Besides number, as in English, Amharic also distinguishes masculine and feminine gender in the singular.

| Number, Gender | Near | Far | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Masculine | ይህ yǝh(ǝ) | ያ ya |

| Feminine | ይቺ yǝčči, ይህች yǝhǝčč | ያቺ yačči |

|

| Plural | እነዚህ ǝnnäzzih | እነዚያ ǝnnäzziya | |

There are also separate demonstratives for formal reference, comparable to the formal personal pronouns: እኚህ ǝññih 'this, these (formal)' and እኒያ ǝnniya 'that, those (formal)'.

The singular pronouns have combining forms beginning with zz instead of y when they follow a preposition: ስለዚህ sǝläzzih 'because of this; therefore', እንደዚያ ǝndäzziya 'like that'. Note that the plural demonstratives, like the second and third person plural personal pronouns, are formed by adding the plural prefix እነ ǝnnä- to the singular masculine forms.

Nouns

Amharic nouns can be primary or derived. A noun like əgər 'foot, leg' is primary, and a noun like əgr-äñña 'pedestrian' is a derived noun.

Gender

Amharic nouns can have a masculine or feminine gender. There are several ways to express gender. An example is the old suffix -t for feminity. This suffix is no longer productive and is limited to certain patterns and some isolated nouns. Nouns and adjectives ending in -awi usually take the suffix -t to form the feminine form, e.g. ityop':ya-(a)wi 'Ethiopian (m.)' vs. ityop':ya-wi-t 'Ethiopian (f.)'; sämay-awi 'heavenly (m.)' vs. sämay-awi-t 'heavenly (f.)'. This suffix also occurs in nouns and adjective based on the pattern qət(t)ul, e.g. nəgus 'king' vs. nəgəs-t 'queen' and qəddus 'holy (m.)' vs. qəddəs-t 'holy (f.)'.

Some nouns and adjectives take a feminine marker -it: ləǧ 'child, boy' vs. ləǧ-it 'girl'; bäg 'sheep, ram' vs. bäg-it 'ewe'; šəmagəlle 'senior, elder (m.)' vs. šəmagəll-it 'old woman'; t'ot'a 'monkey' vs. t'ot'-it 'monkey (f.)'. Some nouns have this feminine marker without having a masculine opposite, e.g. šärär-it 'spider', azur-it 'whirlpool, eddy'. There are, however, also nouns having this -it suffix that are treated as masculine: säraw-it 'army', nägar-it 'big drum'.

The feminine gender is not only used to indicate biological gender, but may also be used to express smallness, e.g. bet-it-u 'the little house' (lit. house-FEM-DEF). The feminine marker can also serve to express tenderness or sympathy.

Specifiers

Amharic has special words that can be used to indicate the gender of people and animals. For people, wänd is used for masculinity and set for femininity, e.g. wänd ləǧ 'boy', set ləǧ 'girl'; wänd hakim 'physician, doctor (m.)', set hakim 'physician, doctor (f.)'. For animals, the words täbat, awra, or wänd (less usual) can be used to indicate masculine gender, and anəst or set to indicate feminine gender. Examples: täbat t'əǧa 'calf (m.)'; awra doro 'cock (rooster)'; set doro 'hen'.

Plural

The plural suffix -očč is used to express plurality of nouns. Some morphophonological alternations occur depending on the final consonant or vowel. For nouns ending in a consonant, plain -očč is used: bet 'house' becomes bet-očč 'houses'. For nouns ending in a back vowel (-a, -o, -u), the suffix takes the form -ʷočč, e.g. wəšša 'dog', wəšša-ʷočč 'dogs'; käbäro 'drum', käbäro-ʷočč 'drums'. Nouns that end in a front vowel pluralize using -ʷočč or -yočč, e.g. s'ähafi 'scholar', s'ähafi-ʷočč or s'ähafi-yočč 'scholars'. Another possibility for nouns ending in a vowel is to delete the vowel and use plain očč, as in wəšš-očč 'dogs'.

Besides using the normal external plural (-očč), nouns and adjectives can be pluralized by way of reduplicating one of the radicals. For example, wäyzäro 'lady' can take the normal plural, yielding wäyzär-očč, but wäyzazər 'ladies' is also found (Leslau 1995:173).

Some kinship-terms have two plural forms with a slightly different meaning. For example, wändəmm 'brother' can be pluralized as wändəmm-očč 'brothers' but also as wändəmmam-ač 'brothers of each other'. Likewise, əhət 'sister' can be pluralized as əhət-očč ('sisters'), but also as ətəmm-am-ač 'sisters of each other'.

In compound words, the plural marker is suffixed to the second noun: betä krəstiyan 'church' (lit. house of Christian) becomes betä krəstiyan-očč 'churches'.

Archaic forms

Amsalu Aklilu has pointed out that Amharic has inherited a large number of old plural forms directly from Classical Ethiopic (Ge'ez) (Leslau 1995:172). There are basically two archaic pluralizing strategies, called external and internal plural. The external plural consists of adding the suffix -an (usually masculine) or -at (usually feminine) to the singular form. The internal plural employs vowel quality or apophony to pluralize words, similar to English man vs. men and goose vs. geese. Sometimes combinations of the two systems are found. The archaic plural forms are not productive anymore, which means that they are not be used to form new plurals.

- Examples of the external plural: mämhər 'teacher', mämhər-an; t'äbib 'wise person', t'äbib-an; kahən 'priest', kahən-at; qal 'word', qal-at.

- Examples of the internal plural: dəngəl 'virgin', dänagəl; hagär 'land', ahəgur.

- Examples of combined systems: nəgus 'king', nägäs-t; kokäb 'star', käwakəb-t; mäs'əhaf 'book', mäs'ahəf-t.

Definiteness

If a noun is definite or specified, this is expressed by a suffix, the article, which is -u or -w for masculine singular nouns and -wa, -itwa or -ätwa for feminine singular nouns. For example:

| masculine sg | masculine sg definite | feminine sg | feminine sg definite |

|---|---|---|---|

| bet | bet-u | gäräd | gärad-wa |

| house | the house | maid | the maid |

In singular forms, this article distinguishes between the male and female gender; in plural forms this distinction is absent, and all definites are marked with -u, e.g. bet-ochch-u 'houses', gäräd-ochch-u 'maids'. As in the plural, morphophonological alternations occur depending on the final consonant or vowel.

Accusative

Amharic has an accusative marker, -(ə)n. Its use is related to the definiteness of the object, thus Amharic shows differential object marking. In general, if the object is definite, the accusative must be used.

| ləǧ-u | wəšša-w-ən | abbarär-ä. |

| child-def | dog-def-acc | chase-3msSUBJ |

| *ləǧ-u | wəšša-w | abbarär-ä. |

| child-def | dog-def-acc | chase-3msSUBJ |

'The child chased the dog.'

The accusative suffix is usually placed after the first word of the noun phrase:

| Yəh-ən | sä’at | gäzz-ä. |

| this-acc | watch | buy-3msSUBJ |

'He bought this watch.'

Nominalization

Amharic has various ways to derive nouns from other words or other nouns. One way of nominalizing consists of a form of vowel agreement (similar vowels on similar places) inside the three-radical structures typical of Semitic languages. For example:

- CəCäC: — t'əbäb 'wisdom'; həmäm 'sickness'

- CəCCaC-e: — wəffar-e 'obesity'; č'əkkan-e 'cruelty'

- CəC-ät: — rət'b-ät 'moistness'; 'əwq-ät 'knowledge'; wəfr-ät 'fatness'.

There are also several nominalizing suffixes.

- -ənna: — 'relation'; krəst-ənna 'Christianity'; sənf-ənna 'laziness'; qes-ənna 'priesthood'.

- -e, suffixed to place name X, yields 'a person from X': goǧǧam-e 'someone from Gojjam'.

- -äñña and -täñña serve to express profession, or some relationship with the base noun: əgr-äñña 'pedestrian' (from əgər 'foot'); bärr-äñña 'gate-keeper' (from bärr 'gate').

- -ənnät and -nnät — '-ness'; ityop'yawi-nnät 'Ethiopianness'; qərb-ənnät 'nearness' (from qərb 'near').

Verbs

Conjugation

As in other Semitic languages, Amharic verbs use a combination of prefixes and suffixes to indicate the subject, distinguishing 3 persons, two numbers and (in the second person singular) two genders.

Gerund

Along with the infinitive and the present participle, the gerund is one of three non-finite verb forms. The infinitive is a nominalized verb, the present participle expresses incomplete action, and the gerund expresses completed action, e.g. ali məsa bälto wädä gäbäya hedä 'Ali, having eaten lunch, went to the market'. There are several usages of the gerund depending on its morpho-syntactic features.

Verbal use

The gerund functions as the head of a subordinate clause (see the example above). There may be more than one gerund in one sentence. The gerund is used to form the following tense forms:

- present perfect nägro -all/näbbär 'He has said'.

- past perfect nägro näbbär 'He had said'.

- possible perfect nägro yəhonall 'He (probably) has said'.

Adverbial use

The gerund can be used as an adverb: alfo alfo yəsəqall 'Sometimes he laughs'. əne dägmo mämt'at əfälləgallähu 'I also want to come'.

Adjectives

Adjectives are words or constructions used to qualify nouns. Adjectives in Amharic can be formed in several ways: they can be based on nominal patterns, or derived from nouns, verbs and other parts of speech. Adjectives can be nominalized by way of suffixing the nominal article (see Nouns above). Amharic has few primary adjectives. Some examples are dägg 'kind, generous', dəda 'mute, dumb, silent', bič'a 'yellow'.

Nominal patterns

- CäCCaC — käbbad 'heavy'; läggas 'generous'

- CäC(C)iC — räqiq 'fine, subtle'; addis 'new'

- CäC(C)aCa — säbara 'broken'; t'ämama 'bent, wrinkled'

- CəC(C)əC — bələh 'intelligent, smart'; dəbbəq' 'hidden'

- CəC(C)uC — kəbur 'worthy, dignified'; t'əqur 'black'; qəddus 'holy'

Denominalizing suffixes

- -äñña — hayl-äñña 'powerful' (from hayl 'power'); əwnät-äñña 'true' (from əwnät 'truth')

- -täñña — aläm-täñña 'secular' (from aläm 'world')

- -awi — ləbb-awi 'intelligent' (from ləbb 'heart'); mədr-awi 'earthly' (from mədr 'earth'); haymanot-awi 'religious' (from haymanot 'religion')

Prefix yä

- yä-kätäma 'urban' (lit. 'from the city'); yä-krəstənna 'Christian' (lit. 'of Christianity'); yä-wəšät 'wrong' (lit. 'of falsehood')

In the same way, a relative perfectum or imperfectum can be used as an adjective by prefixing yä:

- yä-bässälä 'ripe, done' (lit. 'what has been cooked/prepared'); yä-qoyyä 'old' (lit. 'what remained'); yä-mm-ikkättäl 'following' ('that what is following', from tä-kättälä 'to follow'); yä-mm-ittay 'visible' (lit. 'what is seen')

Adjective noun complex

The adjective and the noun together are called the 'adjective noun complex'. In Amharic, the adjective precedes the noun, with the verb last; e.g. kəfu geta 'a bad master'; təlləq bet särra (lit. big house he-built) 'he built a big house'.

If the adjective noun complex is definite, the definite article is suffixed to the adjective and not to the noun, e.g. təlləq-u bet (lit. big-def house) 'the big house'. In a possessive construction, the adjective takes the definite article, and the noun takes the pronominal possessive suffix, e.g. təlləq-u bet-e (lit. big-def house-my) 'my big house'.

When enumerating adjectives using -nna 'and', both adjectives take the definite article: qonǧo-wa-nna astäway-wa ləǧ mät't'ačč (lit. pretty-def-and intelligent-def girl came) 'the pretty and intelligent girl came'. In the case of an indefinite plural adjective noun complex, the noun is plural and the adjective may be used in singular or in plural form. Thus, 'diligent students' can be rendered təgu tämariʷočč (lit. diligent student-PLUR) or təguʷočč tämariʷočč (lit. diligent-PLUR student-PLUR).

Literature in Amharic

There is a growing body of literature in Amharic in many genres. This literature includes government proclamations and records, educational books, religious material, novels, poetry, proverb collections, technical manuals, medical topics, etc. The Holy Bible was first translated into Amharic by Abu Rumi in the early 19th century, but has been retranslated a number of times since. The most famous Amharic novel is Fiqir Iske Meqabir (transliterated various ways) by Haddis Alemayehu (1909–2003), translated into English by Sisay Ayenew with the title Love unto Crypt, published in 2005 (ISBN 978-1-4184-9182-6).

Translation companies

Because of the rapid growth of Ethiopian communities in Europe, the United States and Canada, several public service organizations started to offer Amharic language translation and interpretation services.

Rastafarians

Many Rastafarians learn Amharic as a second language because they consider it to be a sacred language, and even the original language. Various roots reggae musicians including Lincoln Thompson and Misty-in-Roots have written songs in Amharic, thus bringing the sound of this language to a wider audience.

A notable early attempt to use Amharic in reggae was the anthem Satta Amassagana, mistakenly believed to mean "Give thanks". However, this "Amharic" phrase seems to have been derived from looking in a bilingual dictionary and finding the entries säţţä for "give" (actually "he gave") and 'amässägänä for "thank" or "praise" (actually "he thanked" or "he praised"), by those unaware of the correct inflections of these verbs, the convention of always listing verbs in the past tense third person, or the pronunciation of the diacritical marks. The actual way to say "give thanks" is a related word, misgana. Ironically, owing to the vast popularity of this song, "to satta" has even entered modern Rastafarian vocabulary as a verb meaning "to sit down and partake".

Software

The Amharic script is included in Unicode. Now people can post in forums and blogs, send e-mail, or publish Web sites in Amharic. There are several free software programs, and also some commercial ones, for writing in Amharic. Some such software packages are: Keyman, GeezEdit, Hewan Amharic Software, AbeshaSoft and PowerGe'ez. In February 2010, Microsoft released its Windows Vista operating system in Amharic, enabling Amharic speakers to use its operating system in their language.

References

Grammar

- Ethnologue entry for Amharic

- Abraham, Roy Clive (1968). The Principles of Amharic. Occasional Publication / Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan. [rewritten version of 'A modern grammar of spoken Amharic', 1941]

- Afevork Ghevre Jesus (1905) Grammatica della lingua amarica. Roma.

- Afevork Ghevre Jesus (1911) Il verbo amarico. Roma.

- Amsalu Aklilu & Demissie Manahlot (1990) T'iru ye'Amarinnya Dirset 'Indet Yale New! (An Amharic grammar, in Amharic)

- Anbessa Teferra and Grover Hudson. 2007. Essentials of Amharic. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Appleyard, David (1994) Colloquial Amharic, Routledge ISBN 0-415-10003-8

- Bender, M. Lionel. (1974) Phoneme frequencies in Amharic. Journal of Ethiopian Studies 12.1:19-24

- Bender, M. Lionel and Hailu Fulass. (1978). Amharic verb morphology. (Committee on Ethiopian Studies, monograph 7.) East Lansing: African Studies Center, Michigan State University.

- Bennet, M.E. (1978) Stratificational Approaches to Amharic Phonology. PhD thesis, Ann Arbor: Michigan State University.

- Cohen, Marcel (1936) Traité de langue amharique. Paris: Institut d'Ethnographie.

- Cohen, Marcel (1939) Nouvelles études d'éthiopien merdional. Paris: Champion.

- Dawkins, C. H. (¹1960, ²1969) The Fundamentals of Amharic. Addis Ababa.

- Kapeliuk, Olga (1988) Nominalization in Amharic. Stuttgart: F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden. ISBN 3-515-04512-0

- Kapeliuk, Olga (1994) Syntax of the noun in Amharic. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-03406-8.

- Łykowska, Laura (1998) Gramatyka jezyka amharskiego Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog. ISBN 83-86483-60-1

- Leslau, Wolf (1995) Reference Grammar of Amharic. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. ISBN 3-447-03372-X

- Ludolf, Hiob (1698) Grammatica Linguæ Amharicæ. Frankfort.

- Praetorius, Franz (1879) Die amharische Sprache. Halle: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses.

Dictionaries

- Abbadie, Antoine d' (1881) Dictionnaire de la langue amariñña. Actes de la Société philologique, t. 10. Paris.

- Amsalu Aklilu (1973) English-Amharic dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-572264-7

- Baeteman, J.-É. (1929) Dictionnaire amarigna-français. Diré-Daoua

- Gankin, É. B. (1969) Amxarsko-russkij slovar'. Pod redaktsiej Kassa Gäbrä Heywät. Moskva: Izdatel'stvo `Sovetskaja Éntsiklopedija'.

- Guidi, I. (1901) Vocabolario amarico-italiano. Roma.

- Guidi, I. (1940) Supplemento al Vocabolario amarico-italiano. (compilato con il concorso di Francesco Gallina ed Enrico Cerulli) Roma.

- Kane, Thomas L. (1990) Amharic-English Dictionary. (2 vols.) Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-02871-8

- Leslau, Wolf (1976) Concise Amharic Dictionary. (Reissue edition: 1996) Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20501-4

- Täsämma Habtä Mikael Gəṣṣəw (1953 Ethiopian calendar) Käsate Bərhan Täsämma. Yä-Amarəñña mäzgäbä qalat. Addis Ababa: Artistic.

External links

- Links to free Amharic fonts

- Windows Vista Amharic Language Pack

- Free comprehensive Amharic language course USA Foreign Service Institute (FSI)

- An Amharic Reference Grammar by Wolf Leslau (1969) at ERIC

- Amharic Bible at St-Takla.org

- Unicode Ethiopic chartsPDF (250 KB) (Also SupplementalPDF (65.2 KB) and ExtendedPDF (100 KB))

- Voice of America Amharic news broadcasts in Voice of America website

- Christian recordings in Amharic in Global Recordings website

- Selected Annotated Bibliography on Amharic by Grover Hudson at the Michigan State University website.

- GeezEdit Online for Typing in Amharic ግዕዝኤዲት በነፃ by Dr. Aberra Molla

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||