Arnold J. Toynbee

- This page is about the universal historian Arnold Joseph Toynbee; for his uncle, the economic historian Arnold Toynbee, see this article. For further Toynbees and related topics see the disambiguation page Toynbee.

Arnold Joseph Toynbee CH (April 14, 1889 – October 22, 1975) was a British historian whose twelve-volume analysis of the rise and fall of civilizations, A Study of History, 1934-1961, was a synthesis of world history, a metahistory based on universal rhythms of rise, flowering and decline, which examined history from a global perspective. A religious outlook permeates the Study and made it especially popular in the United States, for Toynbee rejected Greek humanism, the Enlightenment belief in humanity's essential goodness, and what he considered the "false god" of modern nationalism. Toynbee in the 1918-1950 period was a leading British consultant to the government on international affairs, especially regarding the Middle East.

Contents |

Biography

Toynbee was the nephew of the economic historian Arnold Toynbee (1852–1883), with whom he is sometimes confused. Born in London, Arnold J. was educated at Winchester College and Balliol College, Oxford. He began his teaching career as a fellow of Balliol College in 1912, and thereafter held positions at King's College London (as Professor of Modern Greek and Byzantine History), the London School of Economics and the Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA) in Chatham House. He was Director of Studies at the RIIA between 1929 and 1956 and from 1920-46 he edited the annual Survey of International Affairs.

His first marriage was to Rosalind Murray (1890 - 1967), daughter of Gilbert Murray, in 1913; they had three sons, of whom Philip Toynbee was the second. They divorced in 1946; Arnold then married Boulter in the same year.

Foreign policy

Toynbee worked for the Political Intelligence Department of the British Foreign Office during World War I and served as a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He was director of studies at Chatham House, Balliol College, Oxford University, 1924-43. Chatham House conducted research for the British Foreign Office and was an important intellectual resource during World War II when it was transferred to London. With his research assistant, Veronica M. Boulter, who was to become his second wife, Toynbee was co-editor of the RIIA's annual Survey of International Affairs. which became the "bible" for international specialists in Britain[1][2] .

Middle East

Toynbee was a leading analyst of developments in the Middle East. His support for Greece and hostility to the Turks during the World War had gained him an appointment to the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History at the University of London. However, after the war he changed to a pro-Turkish position, accusing Greece's military government in occupied Turkish territory of atrocities and massacres. This earned him the enmity of the wealthy Greeks who had endowed the chair, and in 1924 he was forced to resign the position. His stance during World War I reflected less sympathy for the Arab cause and a pro-Zionist outlook. He also expressed support for the Jewish colonization of Palestine, which he believed had "begun to recover its ancient prosperity" as a result. Toynbee investigated Zionism in 1915 at the Information Department of the Foreign Office, and in 1917 he published a memorandum with his colleague Lewis Namier which supported exclusive Jewish political rights in Palestine. In 1922 he was influenced by the Palestine Arab delegation which was visiting London, and he adopted their views. His subsequent writings show the way he changed his outlook on the subject, and in the late 1930s he moved away from supporting the Zionist cause and moved toward the Arab camp. By the 1950s he was an opponent of the state of Israel[3].

Russia

Toynbee was troubled by the Russian Revolution, for he saw Russia as a non-Western society and the revolution as a threat to Western society.[4]

Germany

As an influential opinion shaper, Toynbee was invited to have a private interview with Adolf Hitler in the Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellery) in 1936. Hitler emphasized his limited expansionist aim of building a greater German nation, and his desire for British understanding and cooperation. Toynbee was convinced of Hitler's sincerity, and endorsed Hitler's message in a confidential memorandum for the British prime minister and foreign secretary. During World War II, he again worked for the Foreign Office and attended the postwar peace talks.

Study of History

In 1936-1954, Toynbee's ten-volume A Study of History came out in three separate installments. He followed Oswald Spengler in taking a comparative topical approach to independent civilizations. Toynbee's said they displayed striking parallels in their origin, growth, and decay. Toynbee rejected Spengler's biological model of civilizations as organisms with a typical life span of 1,000 years.

Of the 26 civilizations Toynbee identified, sixteen were dead by 1940 nine of the remaining ten were shown to have already broken down. Only western civilization was lefty standing. He explained breakdowns as a failure of creative power in the creative minority, which henceforth becomes a merely 'dominant' minority; that is followed by an answering withdrawal of allegiance and mimesis on the part of the majority; finally there is a consequent loss of social unity in the society as a whole.[5]

Like Sima Qian in 100 BCE, the father of Chinese historiography, Toynbee explained decline as due to their moral failure. Many readers, especially in America, rejoyced in his implication (in vols. 1-6) that only a return to some form of Catholicism could halt the breakdown of western civilization which began with the Reformation. Volumes 7-10, published in 1954 abandoned the religious message and his popular audience slipped away, while scholars gleefully picked apart his mistakes.

Civilisations

Toynbee's ideas and approach to history may be said to fall into the discipline of Comparative history. While they may be compared to those used by Oswald Spengler in The Decline of the West, he rejected Spengler's deterministic view that civilisations rise and fall according to a natural and inevitable cycle. For Toynbee, a civilization might or might not continue to thrive, depending on the challenges it faced and its responses to them.

Toynbee presented history as the rise and fall of civilisations, rather than the history of nation-states or of ethnic groups. He identified his civilizations according to cultural or religious rather than national criteria. Thus, the "Western Civilisation", comprising all the nations that have existed in Western Europe since the collapse of the Roman Empire, was treated as a whole, and distinguished from both the "Orthodox" civilisation of Russia and the Balkans, and from the Greco-Roman civilisation that preceded it.

With the civilisations as units identified, he presented the history of each in terms of challenge-and-response. Civilisations arose in response to some set of challenges of extreme difficulty, when "creative minorities" devised solutions that reoriented their entire society. Challenges and responses were physical, as when the Sumerians exploited the intractable swamps of southern Iraq by organizing the Neolithic inhabitants into a society capable of carrying out large-scale irrigation projects; or social, as when the Catholic Church resolved the chaos of post-Roman Europe by enrolling the new Germanic kingdoms in a single religious community. When a civilisation responds to challenges, it grows. Civilizations declined when their leaders stopped responding creatively, and the civilisations then sank owing to nationalism, militarism, and the tyranny of a despotic minority. Toynbee argued that "Civilisations die from suicide, not by murder." For Toynbee, civilisations were not intangible or unalterable machines but a network of social relationships within the border and therefore subject to both wise and unwise decisions they made.

He expressed great admiration for Ibn Khaldun and in particular the Muqaddimah (1377), the preface to Ibn Khaldun's own universal history, which notes many systemic biases that intrude on historical analysis via the evidence, and presents an early theory on the cycle of civilisations (Asabiyyah).

Toynbee's view on Indian civilization may perhaps be summarised by the following quotation.

The vast literature, the magnificent, opulence, the majestic sciences, the great realized should, the soul touching music, the awe inspiring gods. It is already becoming clearer that a chapter which has a western beginning will have to have an Indian ending if it is not to end in the self destruction of the human race. At this supremely dangerous moment in history the only way of salvation for mankind is the Indian way[6]

Influence

Toynbee's ideas have annoyed many historians and he was seldom cited after 1960[7]. Comparative history, to which his approach belongs, has been in the doldrums, partly as an adverse reaction to Toynbee.[8] The Canadian economic historian Harold Adams Innis is a notable exception. Following Toynbee and others (Spengler, Kroeber, Sorokin, Cochrane), Innis examined the flourishing of civilizations in terms of administration of empires and media of communication.

Toynbee's overall theory was taken up by some scholars, for example, Ernst Robert Curtius, as a sort of paradigm in the post-war period. Curtius wrote as follows in the opening pages of European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages (1953 English translation), following close on Toynbee, as he sets the stage for his vast study of medieval Latin literature. Not all would agree with his thesis, of course; but his unit of study is the Latin-speaking world of Christendom and Toynbee's ideas feed into his account very naturally:

How do cultures, and the historical entities which are their media, arise, grow and decay? Only a comparative morphology with exact procedures can hope to answer these questions. It was Arnold J. Toynbee who undertook the task. […] Each of these historical entities, through its physical and historical environment and through its inner development, is faced with problems of which it must stand the test. Whether and how it responds to them decides its destiny. […] The economic and social revolutions after the Second Punic War had obliged Rome to import great hordes of slaves from the East. These form an "inner proletariat", bring in Oriental religions, and provide the basis on which Christianity, in the form of a "universal church", will make its way into the organism of the Roman universal state. When after the "interregnum" of the barbarian migrations, the Greco-Roman historical entity, in which the Germanic peoples form an "outer proletariat", is replaced by the new Western historical entity, the latter crystallizes along the line Rome-Northern Gaul, which had been drawn by Caesar. But the Germanic "barbarians" fall prey to the church, which had survived the universal-state end phase of antique culture. They thereby forgo the possibility of bringing a positive intellectual contribution to the new historical entity. […] More precisely: The Franks gave up their language on the soil of Romanized Gaul. […] According to Toynbee, the life curves of cultures do not follow a fatally predetermined course, as they do according to Spengler.

– E R Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, 1953

Reception and criticism

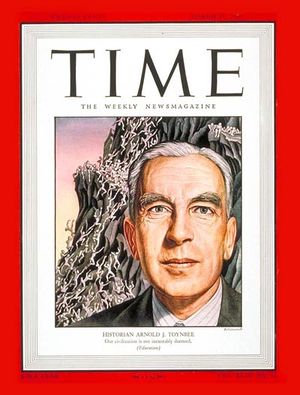

The Idea of History sold well. In the U.S. alone, more than seven thousand sets of the ten-volume edition had been sold by 1955. Most people relied on the very clear one-volume abridgement of the first six volumes by Somervell, which appeared in 1947; it sold over 300,000 copies in the U.S. The high brow press provided innumerable discussions of Toynbee's work in the press, not to mention countless lectures and seminars. Toynbee himself often participated. He appeared on the cover of Time Magazine in 1947[9].

Scholars were much less impressed. Toynbee has been severely criticised by other historians. In general, the critique has been leveled at his use of myths and metaphors as being of comparable value to factual data, and at the soundness of his general argument about the rise and fall of civilisations, which may rely too much on a view of religion as a regenerative force. Many critics complained that the conclusions he reached were those of a Christian moralist rather than of a historian. Hugh Trevor-Roper described Toynbee's work as a "Philosophy of Mish-Mash" - Peter Geyl described Toynbee's ideological approach as "metaphysical speculations dressed up as history" [2]. His work, however, has been praised as a stimulating answer to the specialising tendency of modern historical research.

Toynbee was attacked on numerous fronts in two chapters of Walter Kaufmann's From Shakespeare to Existentialism (1959). One of the charges was that "Toynbee's huge success is confined to the United States where public opinion is heavily influenced by magazines" (p.426); another was his focus on groups of religions as the significant demarcations of the world (p.408), as of 1956. Critics attacked Toynbee's theory for emphasizing religion over other aspects of life when assessing the big pictures of civilizations. In this respect, the debate resembled the contemporary one over Samuel Huntington's theory of the so-called "clash of civilizations". Because he took Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as a related group, and contrasted them with Buddhism, his analysis was very different.

In an essay titled The Chatham House Version (1970), Elie Kedourie of the London School of Economics, a historian of the Middle East, attacked Toynbee's role in what he saw as an abdication of responsibility of the retreating British Empire, in failing democratic values in countries it had once controlled. Kedourie argued that Toynbee's whole system and work were aimed at undercutting this imperial role; he included in this denunciation Toynbee's work at the Foreign Office, where he had dealt directly with the Palestine Mandate.[10]

Franz Borkenau accused Toynbee of anti-semitism.[11]

Family connections

The Toynbees have been prominent in British intellectual society for several generations:

| Joseph Toynbee Pioneering otolaryngologist |

|

Harriet Holmes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arnold Toynbee Economic historian |

|

Harry Valpy Toynbee |

|

Gilbert Murray Classicist and public intellectual |

|

Lady Mary Howard |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Arnold J. Toynbee Universal historian |

|

|

|

Rosalind Murray 1890-1967 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Antony Harry Toynbee 1914-39 |

|

Philip Toynbee Writer and journalist |

|

Anne Powell |

|

Lawrence Toynbee b. 1922 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Josephine Toynbee |

|

Polly Toynbee Journalist |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Allusions in popular culture

Toynbee's ideas also feature in the Ray Bradbury short story named "The Toynbee Convector", and a lesser-known book called Toynbee 22. He appears alongside T. E. Lawrence as a character in an episode of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, dealing with the post-World War I treaty negotiations at Versailles. He also receives a brief mention in the Charles Harness classic, The Paradox Men. Most versions of the Civilization computer game refer to his work as a historian as well. Toynbee receives mention in Pat Frank's post-apocalyptic novel "Alas, Babylon." A character in the P. Schuyler Miller short story "As Never Was" adopts the name Toynbee "out of admiration for a historian of that name".

Works

- The Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation, with a speech delivered by Lord Bryce in the House of Lords (Hodder & Stoughton 1915)

- Nationality and the War (Dent 1915)

- The New Europe: Some Essays in Reconstruction, with an Introduction by the Earl of Cromer (Dent 1915)

- Contributor, Greece, in The Balkans: A History of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Rumania, Turkey, various authors (Oxford, Clarendon Press 1915)

- Editor, The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915-1916: Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Fallodon by Viscount Bryce, with a Preface by Viscount Bryce (Hodder & Stoughton and His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1916)

- The Destruction of Poland: A Study in German Efficiency (1916)

- The Belgian Deportations, with a statement by Viscount Bryce (T. Fisher Unwin 1917)

- The German Terror in Belgium: An Historical Record (Hodder & Stoughton 1917)

- The German Terror in France: An Historical Record (Hodder & Stoughton 1917)

- Turkey: A Past and a Future (Hodder & Stoughton 1917)

- The Western Question in Greece and Turkey: A Study in the Contact of Civilizations (Constable 1922)

- Introduction and translations, Greek Civilization and Character: The Self-Revelation of Ancient Greek Society (Dent 1924)

- Introduction and translations, Greek Historical Thought from Homer to the Age of Heraclius, with two pieces newly translated by Gilbert Murray (Dent 1924)

- Contributor, The Non-Arab Territories of the Ottoman Empire since the Armistice of the 30th October, 1918, in H. W. V. Temperley (editor), A History of the Peace Conference of Paris, Vol. VI (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the British Institute of International Affairs 1924)

- The World after the Peace Conference, Being an Epilogue to the “History of the Peace Conference of Paris” and a Prologue to the “Survey of International Affairs, 1920-1923” (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the British Institute of International Affairs 1925). Published on its own, but Toynbee writes that it was “originally written as an introduction to the Survey of International Affairs in 1920-1923, and was intended for publication as part of the same volume”.

- With Kenneth P. Kirkwood, Turkey (Benn 1926, in Modern Nations series edited by H. A. L. Fisher)

- The Conduct of British Empire Foreign Relations since the Peace Settlement (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs 1928)

- A Journey to China, or Things Which Are Seen (Constable 1931)

- Editor, British Commonwealth Relations, Proceedings of the First Unofficial Conference at Toronto, 11-21 September 1933, with a foreword by Robert L. Borden (Oxford University Press under the joint auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs and the Canadian Institute of International Affairs 1934)

- A Study of History

- Vol I: Introduction; The Geneses of Civilizations

- Vol II: The Geneses of Civilizations

- Vol III: The Growths of Civilizations

-

- (Oxford University Press 1934)

- Editor, with J. A. K. Thomson, Essays in Honour of Gilbert Murray (George Allen & Unwin 1936)

- A Study of History

- Vol IV: The Breakdowns of Civilizations

- Vol V: The Disintegrations of Civilizations

- Vol VI: The Disintegrations of Civilizations

-

- (Oxford University Press 1939)

- D. C. Somervell, A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols I-VI, with a preface by Toynbee (Oxford University Press 1946)

- Civilization on Trial (Oxford University Press 1948)

- The Prospects of Western Civilization (New York, Columbia University Press 1949). Lectures delivered at Columbia University on themes from a then-unpublished part of A Study of History. Published “by arrangement with Oxford University Press in an edition limited to 400 copies and not to be reissued”.

- Albert Vann Fowler (editor), War and Civilization, Selections from A Study of History, with a preface by Toynbee (New York, Oxford University Press 1950)

- Introduction and translations, Twelve Men of Action in Greco-Roman History (Boston, Beacon Press 1952). Extracts from Thucydides, Xenophon, Plutarch and Polybius.

- The World and the West (Oxford University Press 1953). Reith Lectures for 1952.

- A Study of History

- Vol VII: Universal States; Universal Churches

- Vol VIII: Heroic Ages; Contacts between Civilizations in Space

- Vol IX: Contacts between Civilizations in Time; Law and Freedom in History; The Prospects of the Western Civilization

- Vol X: The Inspirations of Historians; A Note on Chronology

-

- (Oxford University Press 1954)

- An Historian's Approach to Religion (Oxford University Press 1956). Gifford Lectures, University of Edinburgh, 1952-1953.

- D. C. Somervell, A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols VII-X, with a preface by Toynbee (Oxford University Press 1957)

- Christianity among the Religions of the World (New York, Scribner 1957; London, Oxford University Press 1958). Hewett Lectures, delivered in 1956.

- Democracy in the Atomic Age (Melbourne, Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Australian Institute of International Affairs 1957). Dyason Lectures, delivered in 1956.

- East to West: A Journey round the World (Oxford University Press 1958)

- Hellenism: The History of a Civilization (Oxford University Press 1959, in Home University Library)

- With Edward D. Myers, A Study of History

- Vol XI: Historical Atlas and Gazetteer

-

- (Oxford University Press 1959)

- D. C. Somervell, A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols I-X in one volume, with a new preface by Toynbee and new tables (Oxford University Press 1960)

- A Study of History

- Vol XII: Reconsiderations

-

- (Oxford University Press 1961)

- Between Oxus and Jumna (Oxford University Press 1961)

- America and the World Revolution (Oxford University Press 1962). Public lectures delivered at the University of Pennsylvania, spring 1961.

- The Economy of the Western Hemisphere (Oxford University Press 1962). Weatherhead Foundation Lectures delivered at the University of Puerto Rico, February 1962.

- The Present-Day Experiment in Western Civilization (Oxford University Press 1962). Beatty Memorial Lectures delivered at McGill University, Montreal, 1961.

-

- The three sets of lectures published separately in the UK in 1962 appeared in New York in the same year in one volume under the title America and the World Revolution and Other Lectures, Oxford University Press.

- Universal States (New York, Oxford University Press 1963). Separate publication of part of Vol VII of A Study of History.

- With Philip Toynbee, Comparing Notes: A Dialogue across a Generation (Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1963). "Conversations between Arnold Toynbee and his son, Philip … as they were recorded on tape."

- Between Niger and Nile (Oxford University Press 1965)

- Hannibal's Legacy: The Hannibalic War's Effects on Roman Life

- Vol I: Rome and Her Neighbours before Hannibal's Entry

- Vol II: Rome and Her Neighbours after Hannibal's Exit

-

- (Oxford University Press 1965)

- Change and Habit: The Challenge of Our Time (Oxford University Press 1966). Partly based on lectures given at University of Denver in the last quarter of 1964, and at New College, Sarasota, Florida and the University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee in the first quarter of 1965.

- Acquaintances (Oxford University Press 1967)

- Between Maule and Amazon (Oxford University Press 1967)

- Editor, Cities of Destiny (Thames & Hudson 1967)

- Editor and principal contributor, Man's Concern with Death (Hodder & Stoughton 1968)

- Editor, The Crucible of Christianity: Judaism, Hellenism and the Historical Background to the Christian Faith (Thames & Hudson 1969)

- Experiences (Oxford University Press 1969)

- Some Problems of Greek History (Oxford University Press 1969)

- Cities on the Move (Oxford University Press 1970). Sponsored by the Institute of Urban Environment of the School of Architecture, Columbia University.

- Surviving the Future (Oxford University Press 1971). Rewritten version of a dialogue between Toynbee and Professor Kei Wakaizumi of Kyoto Sangyo University: essays preceded by questions by Wakaizumi.

- With Jane Caplan, A Study of History, new one-volume abridgement, with new material and revisions and, for the first time, illustrations (Thames & Hudson 1972)

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus and His World (Oxford University Press 1973)

- Editor, Half the World: The History and Culture of China and Japan (Thames & Hudson 1973)

- Toynbee on Toynbee: A Conversation between Arnold J. Toynbee and G. R. Urban (New York, Oxford University Press 1974)

- Mankind and Mother Earth: A Narrative History of the World (Oxford University Press 1976), posthumous

- Richard L. Gage (editor), The Toynbee-Ikeda Dialogue: Man Himself Must Choose (Oxford University Press 1976), posthumous. The record of a conversation lasting several days.

- E. W. F. Tomlin (editor), Arnold Toynbee: A Selection from His Works, with an introduction by Tomlin (Oxford University Press 1978), posthumous. Includes advance extracts from The Greeks and Their Heritages.

- The Greeks and Their Heritages (Oxford University Press 1981), posthumous

- Christian B. Peper (editor), An Historian's Conscience: The Correspondence of Arnold J. Toynbee and Columba Cary-Elwes, Monk of Ampleforth, with a foreword by Lawrence L. Toynbee (Oxford University Press by arrangement with Beacon Press, Boston 1987), posthumous

- The Survey of International Affairs was published by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs between 1925 and 1977 and covered the years 1920-1963. Toynbee wrote, with assistants, the Pre-War Series (covering the years 1920-1938) and the War-Time Series (1938-1946), and contributed introductions to the first two volumes of the Post-War Series (1947-1948 and 1949-1950). His actual contributions varied in extent from year to year.

- A complementary series, Documents on International Affairs, covering the years 1928-1963, was published by Oxford University Press between 1929 and 1973. Toynbee supervised the compilation of the first of the 1939-1946 volumes, and wrote a preface for both that and the 1947-1948 volume.

References

- William H. McNeill (1989). Arnold J. Toynbee: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506335-X.

Further reading

- Ashley Montagu, M. F., ed. Toynbee and History: Critical Essays and Reviews (1956) online edition

- Ben-Israel, Hedva. "Debates With Toynbee: Herzog, Talmon, Friedman," Israel Studies, Spring 2006, Vol. 11 Issue 1, pp 79-90

- Brewin, Christopher. "Arnold Toynbee, Chatham House, and Research in a Global Context," in David Long and Peter Wilson, eds. Thinkers of the Twenty Years' Crisis: Inter-War Idealism Reassessed (1995) pp 277-302.

- Costello, Paul. World Historians and Their Goals: Twentieth-Century Answers to Modernism (1993). Compares Toynbee with H. G. Wells, Oswald Spengler, Pitirim Sorokin, Christopher Dawson, Lewis Mumford, and William H. McNeill

- Friedman, Isaiah. "Arnold Toynbee: Pro-Arab or Pro-Zionist?" Israel Studies, Spring 1999, Vol. 4#1, pp 73-95

- McIntire, C. T. and Marvin Perry, eds. Toynbee: Reappraisals (1989) 254pp

- Martel, Gordon. "The Origins of World History: Arnold Toynbee before the First World War," Australian Journal of Politics and History, Sept 2004, Vol. 50 Issue 3, pp 343-356

- Paquette, Gabriel B. "The Impact of the 1917 Russian Revolutions on Arnold J. Toynbee's Historical Thought, 1917-34," Revolutionary Russia, June 2000, Vol. 13#1, pp 55-80

- Perry, Marvin. Arnold Toynbee and the Western Tradition (1996)

- Toynbee, Arnold J. A Study of History abridged edition by D. C. Somervell (2 vol 1947); 617pp online edition of vol 1, covering vol 1-6 of the original; A Study of History online edition

Notes

- ↑ McNeill, Arnold J. Toynbee (1989)

- ↑ Christopher Brewin, "Arnold Toynbee, Chatham House, and Research in a Global Context," in David Long and Peter Wilson, eds. Thinkers of the Twenty Years' Crisis: Inter-War Idealism Reassessed (1995) pp 277-302

- ↑ Isaiah Friedman, "Arnold Toynbee: Pro-Arab or Pro-Zionist?" Israel Studies, Spring 1999, Vol. 4#1, pp 73-95

- ↑ Gabriel B.. Paquette, "The Impact of the 1917 Russian Revolutions on Arnold J. Toynbee's Historical Thought, 1917-34," Revolutionary Russia, June 2000, Vol. 13#1, pp 55-80

- ↑ Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History (abridged edition 1947) 1:578

- ↑ (Arnold Toynbee, One World and India (Calcutta: Orient Longmans Pvt. Ltd., 1960), p. 54)

- ↑ C. T. McIntire, and Marvin Perry, eds. Toynbee: Reappraisals (1989)

- ↑ Comparative History: Buyer Beware by Deborah Cohen (PDF)

- ↑ Ashley Montagu, ed. Toynbee and History (1956) Page vii

- ↑ Robert John and Sami Hadawi, The Palestine Diary, vol. I (1914-1945), (New World Press, New York, 1970), pp. xiv-xv. Quoted from United Nations Records, Division for Palestinian Rights (DPR) 30 June 1990 The Origins and Evolution of the Palestine Problem: 1917-1988 PART I 1917-1947 “IX. THE ENDING OF THE MANDATE” The transformation of Mandated Palestine c.f. [1].

- ↑ Borkenau, Franz "Toynbee's Judgment of the Jews: Where the Historian Misread History", Commentary May 1955

See also

- Oswald Spengler

- Eric Voegelin

- World history