Astrolabe

An astrolabe (Greek: ἁστρολάβον astrolabon, "star-taker")[1] is a historical astronomical instrument used by astronomers, navigators, and astrologers. Its many uses include locating and predicting the positions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars; determining local time (given local latitude) and vice-versa; surveying; triangulation; and to cast horoscopes. They were used in Classical Antiquity and through the Islamic Golden Age and the European Middle Ages and Renaissance for all these purposes. In the Islamic world, they were also used to calculate the Qibla and to find the times for Salah prayers.

There is often confusion between the astrolabe and the mariner's astrolabe. While the astrolabe could be useful for determining latitude on land, it was an awkward instrument for use on the heaving deck of a ship or in wind. The mariner's astrolabe was developed to address these issues.

Contents |

History

An early astrolabe was invented in the Hellenistic world in 150 BC and is often attributed to Hipparchus. A marriage of the planisphere and dioptra, the astrolabe was effectively an analog calculator capable of working out several different kinds of problems in spherical astronomy. Theon of Alexandria wrote a detailed treatise on the astrolabe, and Lewis (2001) argues that Ptolemy used an astrolabe to make the astronomical observations recorded in the Tetrabiblos.[2]

Astrolabes continued in use in the Greek-speaking world throughout the Byzantine period. About 550 AD the Christian philosopher John Philoponus wrote a treatise on the astrolabe in Greek, which is the earliest extant Greek treatise on the instrument.[3] In addition, Severus Sebokht, a bishop who lived in Mesopotamia, also wrote a treatise on the astrolabe in Syriac in the mid-7th century.[4] It was undoubtedly from such Eastern Christian scholars, either Greek or Syriac-speakers, that Muslim scholars were first introduced to the astrolabe, just as they were introduced by such Eastern Christians to other Greek scientific instruments and texts (including other works by Philoponus). Severus Sebokht refers in the introduction of his treatise to the astrolabe as being made of brass, indicating that metal astrolabes were known in the Christan East well before they were developed in the Islamic world or the Latin West.[5]

Astrolabes were further developed in the medieval Islamic world, where Moslem astronomers introduced angular scales to the astrolabe,[6] adding circles indicating azimuths on the horizon.[7] It was widely used throughout the Muslim world, chiefly as an aid to navigation and as a way of finding the Qibla, the direction of Mecca. The first person credited with building the astrolabe in the Islamic world is reportedly the 8th century mathematician, Muhammad al-Fazari.[8] The mathematical background was established by the Moslem astronomer, Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī (Albatenius), in his treatise Kitab az-Zij (ca. 920 AD), which was translated into Latin by Plato Tiburtinus (De Motu Stellarum). The earliest surviving dated astrolabe is dated AH 315 (927/8 AD). In the Islamic world, astrolabes were used to find the times of sunrise and the rising of fixed stars, to help schedule morning prayers (salat). In the 10th century, al-Sufi first described over 1,000 different uses of an astrolabe, in areas as diverse as astronomy, astrology, horoscopes, navigation, surveying, timekeeping, prayer, Salah, Qibla, etc.[9]

The spherical astrolabe, a variation of both the astrolabe and the armillary sphere, was invented during the Middle Ages by astronomers and inventors in the Islamic world.[10] The earliest description of the spherical astrolabe dates back to Al-Nayrizi (fl. 892-902). In the 12th century, Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī invented the linear astrolabe, sometimes called the "staff of al-Tusi", which was "a simple wooden rod with graduated markings but without sights. It was furnished with a plumb line and a double chord for making angular measurements and bore a perforated pointer."[11] The first geared mechanical astrolabe was later invented by Abi Bakr of Isfahan in 1235.[12]

Peter of Maricourt in the last half of the 13th century also wrote a treatise on the construction and use of a universal astrolabe (Nova compositio astrolabii particularis). Universal astrolabes can be found at the History of Science Museum in Oxford.

The English author Geoffrey Chaucer (ca. 1343–1400) compiled a treatise on the astrolabe for his son, mainly based on Messahalla. The same source was translated by the French astronomer and astrologer Pelerin de Prusse and others. The first printed book on the astrolabe was Composition and Use of Astrolabe by Cristannus de Prachaticz, also using Messahalla, but relatively original.

In 1370, the first Indian treatise on the astrolabe was written by the Jain astronomer Mahendra Suri.[13]

The first known metal astrolabe known in Western Europe was developed in the 15th century by Rabbi Abraham Zacuto in Lisbon. Metal astrolabes improved on the accuracy of their wooden precursors. In the 15th century, the French instrument-maker Jean Fusoris (ca. 1365–1436) also started selling astrolabes in his shop in Paris, along with portable sundials and other popular scientific gadgets of the day.

In the 16th century, Johannes Stöffler published Elucidatio fabricae ususque astrolabii, a manual of the construction and use of the astrolabe. Four identical 16th century astrolabes made by Georg Hartmann provide some of the earliest evidence for batch production by division of labor.

Astrolabes and clocks

At first mechanical astronomical clocks were influenced by the astrolabe; in many ways they could be seen as clockwork astrolabes designed to produce a continual display of the current position of the sun, stars, and planets. For example, Richard of Wallingford's clock (c. 1330) consisted essentially of a star map rotating behind a fixed rete, similar to that of an astrolabe.[14]

Many astronomical clocks, such as the famous clock at Prague, use an astrolabe-style display, adopting a stereographic projection (see below) of the ecliptic plane.

In 1985 Swiss watchmaker Dr. Ludwig Oechslin designed and built an astrolabe wristwatch in conjunction with Ulysse Nardin.

Construction

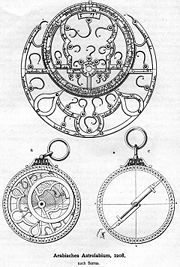

An astrolabe consists of a disk, called the mater (mother), which is deep enough to hold one or more flat plates called tympans, or climates. A tympan is made for a specific latitude and is engraved with a stereographic projection of circles denoting azimuth and altitude and representing the portion of the celestial sphere above the local horizon. The rim of the mater is typically graduated into hours of time, degrees of arc, or both. Above the mater and tympan, the rete, a framework bearing a projection of the ecliptic plane and several pointers indicating the positions of the brightest stars, is free to rotate. Some astrolabes have a narrow rule or label which rotates over the rete, and may be marked with a scale of declinations.

The rete, representing the sky, functions as a star chart. When it is rotated, the stars and the ecliptic move over the projection of the coordinates on the tympan. One complete rotation corresponds to the passage of a day. The astrolabe is therefore a predecessor of the modern planisphere.

On the back of the mater there is often engraved a number of scales that are useful in the astrolabe's various applications; these vary from designer to designer, but might include curves for time conversions, a calendar for converting the day of the month to the sun's position on the ecliptic, trigonometric scales, and a graduation of 360 degrees around the back edge. The alidade is attached to the back face. An alidade can be seen in the lower right illustration of the Persian astrolabe above. When the astrolabe is held vertically, the alidade can be rotated and the sun or a star sighted along its length, so that its altitude in degrees can be read ("taken") from the graduated edge of the astrolabe; hence the word's Greek roots: "astron" (ἄστρον) = star + "lab-" (λαβ-) = to take.

See also

- Antikythera mechanism

- Armillary sphere

- Astrarium

- Astronomical clock

- Cosmolabe

- Equatorium

- Islamic astronomy

- Orrery

- Planetarium

- Planisphere

- Prague Orloj

- Sextant (astronomical)

- Sharafeddin Tusi, the inventor of the linear astrolabe

- Torquetum

- Canterbury Astrolabe Quadrant

- Hypatia

Notes

- ↑ astrolabe, Oxford English Dictionary 2nd ed. 1989

- ↑ Evans (1998:155) "The astrolabe was in fact an invention of the ancient Greeks."

Krebs & Krebs (2003:56) "It is generally accepted that Greek astrologers, in either the first or second centuries BC, invented the astrolabe, an instrument that measures the altitude of stars and planets above the horizon. Some historians attribute its invention to Hipparchus" - ↑ Modern editions of John Philoponus' treatise on the astrolabe are On the Use and Construction of the Astrolabe, ed. H. Hase, Bonn: E. Weber, 1839 (or id. Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 6 (1839): 127-71); repr. and translated into French by A.P. Segonds, Jean Philopon, traité de l'astrolabe, Paris: Librairie Alain Brieux, 1981; and translated into English by H.W. Green in R.T. Gunther, The Astrolabes of the World, Vol. 1/2, Oxford, 1932, repr. London: Holland Press, 1976, pp. 61-81.

- ↑ O'Leary, De Lacy (1948), How Greek Science passed to the Arabs, Routledge and Kegan Paul, http://www.aina.org/books/hgsptta.htm "The most distinguished Syriac scholar of this later period was Severus Sebokht (d. 666-7), Bishop of Kennesrin. [...] In addition to these works [...] he also wrote on astronomical subjects (Brit. Mus. Add. 14538), and composed a treatise on the astronomical instrument known as the astrolabe, which has been edited and published by F. Nau (Paris, 1899)."

Severus' treatise was translated by Jessie Payne Smith Margoliouth in R.T. Gunther, Astrolabes of the world Oxford, 1932, p. 82-103. - ↑ Severus Sebokht, Description of the astrolabe http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/severus_sebokht_astrolabe_01_trans.htm

- ↑ See p. 289 of Martin, L. C. (1923), "Surveying and navigational instruments from the historical standpoint", Transactions of the Optical Society 24 (5): 289–303, doi:10.1088/1475-4878/24/5/302, ISSN 1475-4878, http://iopscience.iop.org/1475-4878/24/5/302/.

- ↑ Victor J. Katz & Annette Imhausen (2007), The mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: a sourcebook, Princeton University Press, p. 519, ISBN 0691114854

- ↑ Richard Nelson Frye: Golden Age of Persia. p. 163

- ↑ Dr. Emily Winterburn (National Maritime Museum), Using an Astrolabe, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, 2005.

- ↑ Emilie Savage-Smith (1993). "Book Reviews", Journal of Islamic Studies 4 (2), p. 296-299.

"There is no evidence for the Hellenistic origin of the spherical astrolabe, but rather evidence so far available suggests that it may have been an early but distinctly Islamic development with no Greek antecedents."

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Sharaf al-Din al-Muzaffar al-Tusi", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Tusi_Sharaf.html.

- ↑ Silvio A. Bedini, Francis R. Maddison (1966). "Mechanical Universe: The Astrarium of Giovanni de' Dondi", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 56 (5), p. 1-69.

- ↑ Glick et al., eds. (2005), Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, pp. 464, ISBN 0415969301

- ↑ John David North, "God's Clockmaker: Richard of Wallingford and the Invention of Time", Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 978-1-85285-451-5

References

- Evans, James (1998), The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195095391.

- Alessandro Gunella and John Lamprey, Stoeffler's Elucidatio (translation of Elucidatio fabricae ususque astrolabii into English). Published by John Lamprey, 2007. [email protected]

- Krebs, Robert E.; Krebs, Carolyn A. (2003), Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Ancient World, Greenwood Press.

- Lewis, M. J. T. (2001), Surveying Instruments of Greece and Rome, Cambridge University Press.

- Morrison, James E (2007), The Astrolabe, Janus, ISBN 9780939320301.

- John North. God's Clockmaker, Richard of Wallingford and the invention of time. Hambledon and London, 2006.

- Critical edition of Pelerin de Prusse on the Astrolabe (translation of Practique de Astralabe). Editors Edgar Laird, Robert Fischer. Binghamton, New York, 1995, in Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies. ISBN 0-86698-132-2

- King, Henry Geared to the Stars: the evolution of planetariums, orreries, and astronomical clocks University of Toronto Press, 1978

External links

- Video of Tom Wujec demonstrating an astrolabe. Taken at TEDGlobal 2009. Includes clickable transcript. Licensed as Creative Commons by-nc-nd.

- The Astrolabe

- Keith's Astrolabe, a software astrolabe simulator and tutorial written in Java

- Shadows Pro, a Windows software for the design of astrolabes

- A working model of the Dr. Ludwig Oechslin's Astrolabium Galileo Galilei watch

- Ulysse Nardin Astrolabium Galilei Galileo: A Detailed Explanation

- Fully illustrated online catalogue of world's largest collection of astrolabes

- Gerbert d'Aurillac's use of the Astrolabe at Convergence

- Mobile astrolabe that instantly shows the local astrolabe from any spot of the earth

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||