Battle of Leuctra

| Battle of Leuctra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the post-Peloponnesian War conflicts | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Boeotian League (Thebes) | Sparta | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Epaminondas | Cleombrotus I † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,000–7,000 hoplites 1,500 cavalry |

10,000–11,000 hoplites 1,000 cavalry |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 300 according to Diodorus, 47 according to Pausanias | 1,000 according to Xenophon, 4,000+ According to Diodorus | ||||||

|

|||||

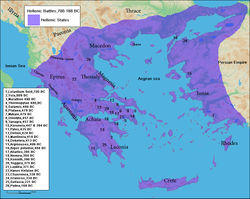

The Battle of Leuctra (or Leuktra) was a battle fought on July 6, 371 BC, between the Thebans and the Spartans and their respective allies amidst the post-Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the neighbourhood of Leuctra, a village in Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae. Theban victory weakened Sparta’s immense influence over the Greek peninsula which Sparta had gained since its victory in the Peloponnesian War.

Contents |

Prelude

In 379 BC the newly established democracy of Thebes had elected 4 Boeotarchs, the traditional title of the generals of the Boeotian League and so proclaimed their intention of reconstituting the League that Sparta had disbanded.[2] During this period Thebes had had an ally in Athens but Athens was far from happy with the treatment Plataea had received.[2] When it came to swearing an oath to respect the treaty, Sparta swore on behalf of herself and her allies. When Epaminondas came forward asking to swear on behalf of the whole Boeotian League, the Spartans refused saying he could swear as the representative of Thebes or not at all. This Epaminondas refused.[3] (According to Xenophon, the Thebans signed as "the Thebans", and asked the next day to change their signature to "the Boeotians", but the Spartan king Agesilaus would not allow it.)[4] In this Sparta saw an opportunity to reassert their shaky authority in central Greece.[5] Hence, they ordered the Spartan King Cleombrotus I to march to war from Phocis.

Rather than take the expected, easy route into Boeotia through the usual defile, the Spartans marched over the hills via Thisbae and took the fortress of Creusis (along with twelve Theban warships) before the Thebans were aware of their presence. It was here that a Peloponnesian army, about 10,000–11,000 strong, which had invaded Boeotia from Phocis, was confronted by a Boeotian levy of perhaps 6,000–7,000 soldiers. Initially the six Boetian generals (i.e. the Boeotarchs) present were divided as to whether to offer battle, with Epaminondas being the main advocate in favor of battle. Only when a seventh arrived who sided with Epaminondas was the decision made.[6] In spite of inferior numbers and the doubtful loyalty of his Boeotian allies, the Boetians would offer battle on the plain before the town.

Battle

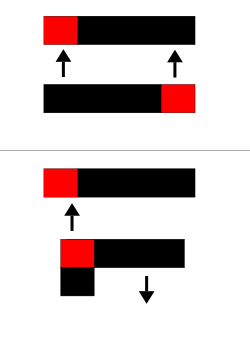

Bottom: Epaminondas's strategy at Leuctra. The strong left wing advanced more than the weaker right wing. The red blocks show the placement of the elite troops within each phalanx.

The battle opened with the Spartans' mercenary peltasts (slingers, javeliniers, and/or skirmishers) attacking and driving back the Boeotian camp followers and others who were reluctant to fight. According to Xenophon, the Boeotian camp followers were trying to leave the field, as they did not intend to fight; this Spartan action drove them back into the Theban army, inadvertently making the Theban force stronger.[7] There followed a cavalry engagement, in which the Thebans drove their enemies off the field. Initially, the Spartan infantry were sent into disarray when their retreating cavalry hopelessly disrupted Cleombrotus's attempt to outflank the Theban left column. At this point the Theban left hit the Spartan right with the Sacred Band of Thebes led by Pelopidas[8] at its head. The decisive issue was then fought out between the Theban and Spartan foot.

The normal practice of the Spartans (and, indeed, the Greeks generally) was to establish their heavily armed infantry in a solid mass, or phalanx, some eight to twelve men deep. This was considered to allow for the best balance between depth (the pushing power it provided) and width (i.e., area of coverage of the phalanx's front battle line). The infantry would advance together so that the attack flowed unbroken against their enemy. In order to combat the phalanx's infamous right-hand drift (see article phalanx for further information), Greek commanders traditionally placed their most experienced, highly regarded and, generally, deadliest troops on the right wing as this was the place of honour. By contrast, the shakiest and/or least influential troops were often placed on the left wing. In the Spartan battleplan therefore, the hippeis (an elite force numbering 300 men) and the king of Sparta would stand on the right wing of the phalanx.

In a major break with tradition, Epaminondas massed his cavalry and a fifty-deep column of Theban infantry on his left wing, and sent forward this body against the Spartan right. His shallower and weaker center and right wing columns were drawn up so that they were progressively further to the right and rear of the proceeding column, in the so-called Echelon formation. The footsoldiers engaged, and the Spartans' twelve-deep formation on their right wing could not sustain the heavy impact of their opponents' 50-deep column. Xenophon insists that Spartans initially were able to hold back the gigantic mass of the Thebans, however they were eventually overwhelmed.[9] The Spartan right was hurled back with a loss of about 1,000 men, of whom 400 were Spartan citizens, including the king Cleombrotus I.

Rüstow and Kochly, writing in the 19th Century, believed that Pelopidas led the Sacred Band out from the column to attack the Spartans in the flank. Hans Delbrück considered this to be a mere misreading of Plutarch. Plutarch does indeed describe Pelopidas leading the band and catching the Spartans in disorder but there is nothing in his account that conveys anything other than the Sacred Band being the head of the column and the Spartans were disordered not because they were taken in the flank but because they were caught in mid-manoeuvre, extending their line.[10]

Seeing their right wing beaten, the rest of the Peloponnesians, who were essentially unwilling participants, retired and left the enemy in possession of the field.

After the Battle

The arrival of a Thessalian army under Jason of Pherae persuaded a relieving Spartan force under Archidamus not to heap folly on folly and to withdraw instead, while the Thebans were persuaded not to continue the attack on the surviving Spartans. The Thebans somewhat bent the rules by insisting on conditions under which the Spartans and allies recovered the dead and by erecting a permanent rather than perishable trophy - something that was criticized by later writers.[11]

Historical significance

The battle is of great significance in Greek history, and, by extension, European history. Epaminondas not only broke away from the traditional tactical methods of his time, but marked a revolution in military tactics, affording the first known instance of an oblique infantry deployment and one of the first deliberate concentrations of attack upon the vital point of the enemy's line. The new tactics of the phalanx, introduced by Epaminondas, employed for the first time in the history of war the modern principle of local superiority of force.[1]

The use of these tactics by Epaminondas was, perhaps, a direct result of the use of some similar maneuvers by Pagondas, his countryman, during the Battle of Delium. Further, Philip II of Macedon, who studied and lived in Thebes, was no doubt heavily influenced by the battle to develop his own, highly effective approach to tactics and armament. In turn, his son Alexander would go on to develop his father's theories to an entirely new level.

Historians Victor Davis Hanson and Donald Kagan have argued that Epaminondas's so-called "oblique formation" was not an intentional and preconceived innovation in infantry tactics, but was rather a clever response to circumstances. Because Epaminondas had stacked his left wing to a depth of fifty shields, the rest of his units were naturally left with far fewer troops than normal. This means that their maintenance of a depth of eight to twelve shields had to come at the expense of either number of companies or their width. Because Epaminondas was already outnumbered, he had no choice but to form fewer companies and march them diagonally toward the much longer Spartan line in order to engage as much of it as possible. Hanson and Kagan's argument is therefore that the tactic was more dilatory than anything else. Whatever its motivation, the fact remains that the tactic did represent an innovation and was undoubtedly highly effective.

The battle's political effects were far-reaching: the losses in material strength and prestige (prestige being an inestimably important factor in the Peloponnesian War) sustained by the Spartans at Leuctra and subsequently at the Battle of Mantinea were key in depriving them forever of their supremacy in Greece. Therefore, the battle permanently altered the Greek balance of power, as Sparta was deprived of her former prominence and was reduced to a second-rate power among the Greek city-states.

Theban supremacy in Greece was short-lived as it was subsequently lost to the Macedonians led by Philip II.[12]

Popular culture

The battle is fictionalised, though in some detail, in David Gemmell's book, Lion of Macedon, which includes the significant deviation from historical canon is that it is credited to a young Parmenio(n) instead of Epaminondas, who serves merely to gain permission to carry out the echelon tactic.

Notes

- ↑ The Battle of Leuctra, retrieved 1-08-2006

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tritle 1987, p. 80

- ↑ History of Greece, G. Grote vol. 9 p. 155-6

- ↑ Hellenica VI 3.19

- ↑ Tritle 1987, p. 81

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece

- ↑ Hellenica VI 4.8

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos: Lives of Eminent Commanders, Pelopidas

- ↑ Hellenica VI 4.13

- ↑ The History of the Art of War, Hans Delbrück p167

- ↑ Greek Warfare, Myths and Realities, Hans van Wees p136

- ↑ The Battle of Leuktra, retrieved 07-07-2010

References

- Xenophon, Hellenica, vi. 4. 3–15

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliother Historica, xv. 53–56

- Plutarch, "Pelopidas," 20–23

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, ix. 13. 2-12

- Tritle, Lawrence A. The Greek World In The Fourth Century (1987) Routledge. ISBN 041510582X. Also paperback 1997, ISBN 0415105838

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Battle of Leuctra animated battle map by Jonathan Webb

- Battle of Leuctra from Encyclopædia Britannica