Battle of San Jacinto

| Battle of San Jacinto | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Texas Revolution | |||||||

.jpg) The Battle of San Jacinto-1895 painting by Henry Arthur McArdle (1836-1908) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Antonio López de Santa Anna (P.O.W.) Manuel Fernández Castrillón † Juan Almonte (P.O.W.) |

Sam Houston W | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,360 1 cannon |

910[1] 2 cannons |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 630 killed 208 wounded 730 captured |

9 killed 30 wounded |

||||||

|

|||||

The Battle of San Jacinto, fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day Harris County, Texas, was the decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Sam Houston, the Texas Army engaged and defeated General Antonio López de Santa Anna's Mexican forces in a fight that lasted just eighteen minutes. About 700 of the Mexican soldiers were killed and 730 captured, while only nine Texans died.[2]

Santa Anna, the President of Mexico, was captured the following day and held as a prisoner of war. Three weeks later, he signed the peace treaties that dictated that the Mexican army leave the region, paving the way for the Republic of Texas to become an independent country. These treaties did not specifically recognize Texas as a sovereign nation, but stipulated that Santa Anna was to lobby for such recognition in Mexico City. Sam Houston became a national celebrity, and the Texans' rallying cries, "Remember the Alamo!" and "Remember Goliad!" became etched into American history and legend.

Contents |

Background

During the early years of Mexican independence, numerous American immigrants had settled in Mexican Texas, then a part of the state of Coahuila y Tejas, with the Mexican government's encouragement. In 1835 they rebelled against the Mexican government of Santa Anna because he rescinded the democratic Constitution of 1824, dissolved Mexico's Congress and state legislatures, and asserted dictatorial control over the nation. After capturing a few small outposts and defeating the Mexican army garrisons in the area, the Texans formed a provisional government and drafted a Declaration of Independence.

Hundreds of volunteers from the United States of America headed into the fledgling Republic of Texas to assist in its quest for independence. Two full regiments of these volunteers were soon organized to augment the Regular Texas Army. Other volunteers (including Tejano and Texian colonists), organized into companies to defend places that might be targets of Mexican intervention. For example, American volunteers at San Jacinto included the Kentucky Rifles, a uniformed company raised in Cincinnati and northern Kentucky by Sidney Sherman, who were the only troops in the Texian army that wore formal uniforms. The New Orleans Greys, another company raised in the United States, had fought and died at the Battle of the Alamo while serving under a regular Texas army officer, while two companies from Alabama (one each from Huntsville and Mobile) fought and died at Goliad.

In 1836, Santa Anna personally led a force of about 3,000–5,000 Mexican troops into what is now Texas to put down the insurrection. He first entered San Antonio de Béxar and, after a 13-day siege, defeated and slaughtered a Texan force on March 6, 1836 at the Alamo. The right wing of Santa Anna's offensive, under General José de Urrea, then defeated, captured, and murdered the survivors of a second force near Goliad after disarming them. Santa Anna ordered the prisoners (about 350) to be shot or bayoneted on March 27 (Palm Sunday). Gen. Urrea resisted the orders at first and sent a special message to Santa Anna to confirm the order, which Santa Anna upheld. Urrea refused to shoot the Texian doctors - since they had not carried arms - and eventually released them. A practical problem was how to shoot 350 prisoners of war. To do so he told them that they were being moved under guard to a new location. When moving down the road prisoners moved single file on the right with a Mexican guard to his left. At a signal on the road, each guard turned and slew his man, some with rifle, others with sword or bayonet. In the melee six prisoners escaped and carried the tale to Sam Houston's army, and this became known as the Goliad massacre. At the Battle of San Jacinto, both the cries of "Remember the Alamo!" and "Remember Goliad!" were heard. The fortress where the prisoners were held for one week before execution is today in excellent repair and is the finest example of a Mexican fort in the United States. It is called Presidio de la Bahia and is near present day Goliad TX.

Houston, in command of the main Texan army, slowly retreated eastward. To President David G. Burnet, no admirer of Houston's, Houston appeared unwilling to fight his pursuer, despite Burnet's frequent orders that Houston do so. Texas settlers jeered Houston as he passed and his officers threatened to seize command. Houston in reply said he would shoot anyone who tried.[3] Concerned that the Mexican Army was rapidly approaching unchecked, Burnet and the Texas government abandoned the provisional capital at Washington-on-the-Brazos and moved towards the Gulf of Mexico, reestablishing key governmental functions in Harrisburg and later Galveston. In their wake, thousands of panicked colonists (both Texian and Tejano) fled in what became popularly known as the "Runaway Scrape."[3][4]

Houston initially headed toward the Sabine River, the border with the United States, where a Federal army under General Pendleton Gaines had assembled to protect Louisiana if Santa Anna decided to invade the U.S. However, Houston soon turned to southeast toward Harrisburg.

Santa Anna pursued Houston and devised a plan in which three columns of Mexican soldiers would converge on Houston's force and destroy it. However, he diverted one column in an attempt to capture the provisional government, and a second to protect his supply lines. Santa Anna personally led the remaining column of about 900 troops against Houston. He caught up with Houston on April 19 near Lynch's Ferry. Forced to cross Vince's Bridge, he established positions on less than 3 sq mi (8 km2) of ground completely surrounded by the San Jacinto River (Texas), the flooded Buffalo and Vince Bayous, and marshes and bay on the east and southeast. Houston established his camp on a grassy field 1,000 yards (914 m) away.

Prelude to battle

Believing Houston to be cornered, Santa Anna decided to rest his army on April 19 and attack on April 22. He received roughly 500 reinforcements under General Martín Perfecto de Cos, bringing his total strength up to roughly 1,400 men (2 Battalions = 2 Regiments). Santa Anna posted Cos to his right, near the river, and posted his last artillery in the center, erecting a five-foot (1.5 m) high barricade of packs and baggage as hastily constructed protection for his infantry. He placed his veteran cavalry on his left flank and settled back to plan the following day's attack.

On the morning of April 21, Houston held a council of war, and the majority of his officers favored waiting for Santa Anna's eventual assault. Houston, however, decided in favor of his own surprise attack that afternoon, concerned that Santa Anna might use the extra time to concentrate his scattered army. With his army of roughly 900 men, he decided to attack Santa Anna. Most of the assault would come over open ground, where the Texan infantry would be vulnerable to Mexican gunfire. Even riskier, Houston decided to outflank the Mexicans with his cavalry, stretching his troops even thinner. However, Santa Anna made a crucial mistake — during his army's afternoon siesta, he failed to post sentries or skirmishers around his camp.

Houston soon gained approval for his daring plan from Texas Secretary of War Thomas J. Rusk, who had caught up with the army to consult with Houston at the insistence of President Burnet. By 3:30 p.m., Houston had formed his men into battle lines for the impending assault, screened from Mexican view by trees and by a slight ridge that ran across the open prairie between the opposing armies. Santa Anna's failure to properly post lookouts proved fatal to his chances of victory.

Battle

At 4:30 p.m. on April 21, scout Deaf Smith (pronounced "Deef Smith") announced the burning of Vince's Bridge, which cut off the only avenue of retreat for both armies without having to cross water more than 10 feet (3.0 m) deep. The main Texan battle line moved forward with their approach screened by the trees and rising ground. Emerging from the woods, the order was given to "advance" and a fifer began playing the popular tune "Will you come to the bower I have shaded for you?"[2][6] General Houston personally led the infantry, posting the 2nd Volunteer Regiment of Colonel Sidney Sherman on his far left, with Colonel Edward Burleson's 1st Volunteer Regiment next in line. In the center, two small brass (or iron) smoothbore artillery pieces (donated by citizens of Cincinnati, Ohio) known as the "Twin Sisters," (replicas pictured right) were wheeled forward under the command of Major George W. Hockley. They were supported by four companies of infantry under Captain Henry Wax Karnes. Colonel Henry Millard's regiment of Texas regulars made up the right wing. To the extreme far right, 61 Texas cavalrymen under newly promoted Colonel Mirabeau B. Lamar planned to circle into the Mexicans' left flank.[7] Lamar had, the day before, been a private in the cavalry but his daring and resourcefulness in a brief skirmish with the Mexicans on April 20 had led to his immediate promotion to colonel.

The Texan army moved quickly and silently across the high-grass plain, and then, when they were only a few dozen yards away, charged Santa Anna's camp shouting "Remember the Alamo!" and "Remember Goliad!," only stopping a few yards from the Mexicans to open fire. The Texans achieved complete surprise. It was a bold attack in broad daylight but its success can be attributed in good part to Santa Anna's failure to post guards during the army's siesta. Santa Anna's army primarily consisted of professional soldiers, but they were trained to fight in ranks, exchanging volleys with their opponents. The Mexicans were ill-prepared and unarmed at the time of the sudden attack. Most were asleep with their soldaderas (i.e., wives and female soldiers), some were out gathering wood, and the cavalrymen were riding bareback fetching water. General Manuel Fernández Castrillón desperately tried to mount an organized resistance, but was soon shot down and killed. His panicked troops fled, and Santa Anna's defensive line quickly collapsed.

Hundreds of the demoralized and confused Mexican soldiers were routed, with many being driven into the marshes along the river to drown. The Texans chased after the fleeing enemy, shouting "take prisoners like the Meskins do!", in reference to the burning of bodies after the Alamo and the mass murder of Texans at Goliad. Some of the Mexican cavalry plunged into the flooded stream by Vince's bridge but they were shot as they struggled in the water. Houston tried to restrain his men but was ignored. Gen. Juan Almonte, commanding what was left of the organized Mexican resistance, soon formally surrendered his 400 remaining men to Rusk. The rest of Santa Anna's once-proud army had disintegrated into chaos. From the moment of the first charge the battle was a slaughter, "frightful to behold", with most of the Texan casualties coming in the first minutes of battle from the first Mexican volley.[8]

During the short but furious fighting, Houston was shot in the left ankle, two of his horses were shot from under him, and Santa Anna escaped. The combat itself lasted 18 minutes but the slaughter of the Mexicans continued for "another hour or so".[3][9] The Texan army had won a stunning victory, killing about 700 Mexican soldiers, wounding 208, and taking 730 prisoners while suffering 9 killed and 30 wounded.[10]

Aftermath

During the battle, Santa Anna disappeared and a search party consisting of James A. Sylvester, Washington H. Secrest, Sion R. Bostick, and a Mr. Cole was sent out the next morning. However, Santa Anna shed his ornate uniform to elude discovery. It was not until he was saluted as "El Presidente" that suspicion was narrowed. Unfortunately for Santa Anna, it was well known that he wore silk underwear. So, when it was discovered that this same person who had been saluted was also wearing silk underwear, the Texans knew they had captured Santa Anna. Houston spared his life, preferring to negotiate an end to the overall hostilities and the withdrawal from Texas of Santa Anna's remaining columns.

On May 14, 1836, Santa Anna signed the Treaties of Velasco, in which he agreed to withdraw his troops from Texan soil and, in exchange for safe conduct back to Mexico, lobby there for recognition of the new republic. There were 2 treaties, a private treaty and a public treaty. In the private treaty, Santa Anna pledged to try to persuade Mexico to acknowledge Texas' independence, in return for an escort back to Mexico. However, the safe passage never materialized; Santa Anna was held for six months as a prisoner of war (during which time his government disowned him and any agreement he might enter into) and finally taken to Washington, D.C. There he met with President Andrew Jackson, before finally returning in disgrace to Mexico in early 1837. By then, however, Texas independence was a fait accompli, although Mexico did not officially recognize it until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War in 1848.

Legend

It was well known that when on campaign, Santa Anna would send aides to round up the prettiest women for his pleasure. According to legend, he was "entertaining" a mulatto woman named Emily Morgan at the time of opening salvo. A song titled "The Yellow Rose of Texas" was later written about Emily Morgan's role in the battle. No primary source evidence corroborates this story, however, and it is now dismissed by historians.[11]

Memorialization

Today, the San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site commemorates the battle and includes the San Jacinto Monument, the world's tallest memorial column, at 570 feet. The park is located near Deer Park, about 25 miles (40 km) east of downtown Houston. The monument contains an inscription, part of which reads:

Measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom of Texas (not part of the United States at the time) from Mexico won here led to annexation and to the Mexican-American War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American Nation, nearly a million square miles of territory, changed sovereignty.

Both the Texas Navy and the United States Navy commissioned ships named after the Battle of San Jacinto: the Texan schooner San Jacinto and the USS San Jacinto.

An annual San Jacinto Day festival and battle reenactment is held in the month of April at the San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site.[12]

The annual Fiesta celebration in San Antonio with three large parades, banquets, and numerous other events, celebrates the victory of San Jacinto and Texas independence.

Alfonso Steele, to whom a roadside park is dedicated in Limestone County, Texas, is generally credited as being the last remaining Texan survivor of the battle, however W.T. Zuber who was a member of the rear guard died at 93 in 1913 and is now considered the last remaining Texan survivor of the battle. S.F. Sparks was the last president of the Texas Veterans Association, died 1908 age 89 in Rockport. According to Dixon and Kemp in Heroes of San Jacinto, Alfonso Steele was the last survivor of San Jacinto, died 1911 age 94 at Mexia probably because the authors did not consider those assigned to the rear guard as participants. More modern sources indicate that W.T. Zuber who was a member of the rear guard who died at age 93 in 1913 was the last. In the 20th century, the state of Texas erected various monuments and historical wayside markers to mark the path and campsites of Houston's army as it marched to San Jacinto.

See also

- List of Texas Revolution battles

- Timeline of the Texas Revolution

Notes

- ↑ The official report of the battle claims 783. The more detailed roster published after the battle lists 845 officers and men but failed to include Captain Wyly's Company giving a total of around 910.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Texas State Historical Commission. "Battle of San Jacinto Historical Marker". http://www.stoppingpoints.com/texas/sights.cgi?marker=Battle+of+San+Jacinto&cnty=harris.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ward, Geoffrey C. (1996), The West: An Illustrated History, Orion Publishing, ISBN 0 297 82181 4

- ↑ One settler recalled: "We passed a house with all the doors open, the table had been set, all the victuals on the table....a plate of biscuits, a plate of potatoes, a plate of chicken..."

- ↑ Winkler, EW (2006-01-23), "The "Twin Sisters" Cannon, 1836–1865", Southwestern Historical Quarterly (The Texas State Historical Association) 21 (1): 61–8, http://www.tshaonline.org/publications/journals/shq/online/v021/n1/article_6.html, retrieved 2009-03-06

- ↑ Some primary accounts (veterans of the battle) insist that the fifer's tune was actually "Yankee Doodle." Battle of San Jancinto, http://www.tamu.edu/ccbn/dewitt/batsanjacinto.htm

- ↑ Description of the Battle of San Jacinto, http://www.tamu.edu/ccbn/dewitt/batsanjacinto.htm

- ↑ The Battle of San Jacinto tamu.edu

- ↑ From an account of the battle by a Texian Sergeant: "A young Mexican boy, a drummer I suppose, (was) lying on his face. One of the volunteers pricked the boy with his bayonet. The boy grasped the man around the ankles and cried out in Spanish "Hail Mary most pure, for God's sake spare my life". I begged the man to spare him, both of his legs being broken already. The man looked at me and put his hand on his pistol, so I passed on. As I did so he blew the boy's brains out."

- ↑ Casualty figures, tamu.edu, http://www.tamu.edu/ccbn/dewitt/batsanjacinto.htm

- ↑ Rodríguez, Juan Carlos (2007-12-20), "The Yellow Rose of Texas", Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Society, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/YY/xey1.html, retrieved 2009-03-06

- ↑ San Jacinto Day Festival and Battle Reenactment: Festival celebrates 170th anniversary of battle, Houston, TX, USA: San Jacinto Museum, 2006-01, http://web.archive.org/web/20070927081929/http://www.sanjacinto-museum.org/About_Us/News_and_Events/2006_Festival_Reenactment/, retrieved 2009-03-06

Further reading

- Maher, Ramona; Gammell, Stephen; Rohr, John A. (1974), The Glory Horse: A Story of the Battle of San Jacinto and Texas in 1836, Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, ISBN 9780698202945

- Moore, Stephen L. (2004), Eighteen Minutes: The Battle of San Jacinto and the Texas Independence Campaign, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 9781589070097

- Pohl, James W. (1989), The Battle of San Jacinto, Texas State Historical Association, ISBN 9780876110843

- Tolbert, Frank X. (1969), The Day of San Jacinto, Jenkins Publishing Company

External links

- Battle of San Jacinto – Handbook of Texas Online

- Young Perry Alsbury Letter

- Santa Anna's Letter

- Santa Anna's Account of the Battle

- Account of the battle by Creed Taylor

- San Jacinto

- Vince's Bridge

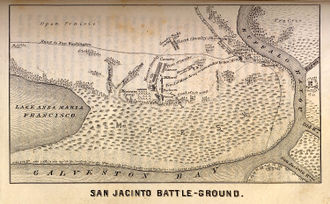

- 1856 map of the San Jacinto Battle-ground hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Schematic of San Jacinto Battle-ground showing troop deployment and movements.

- Map of the Battle Ground of San Jacinto from A pictorial history of Texas, from the earliest visits of European adventurers, to A.D. 1879, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- True veterans of Texas: an authentic account of the Battle of San Jacinto : a complete list of heroes who fought, bled and died at San Jacinto, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Battle of San Jacinto – The Sons of DeWitt Colony

- Battle of San Jacinto – Texas State Library

- Memorial aerial view

- Flags of Guerrero and Matamoros Battalions – Texas State Library and Archives Commission

- Battle of San Jacinto from Yoakum's History of Texas, 1855

- San Jacinto Monument & Museum

- Sam Houston's official report on the Battle of San Jacinto – TexasBob.com

- Battle of San Jacinto, A Mexican prospective - Pedro Delgado in 1837 – TexasBob.com

- Invitation to a Ball Celebrating Battle of San Jacinto, April 10, 1839 From Texas Tides

- Junius William Mottley killed in the battle

- 2010 San Jacinto Day Ceremony

|

||||||||||||||