But I'm a Cheerleader

| But I'm a Cheerleader | |

|---|---|

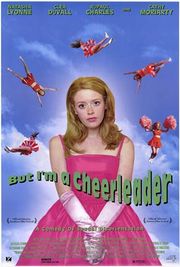

Original film poster |

|

| Directed by | Jamie Babbit |

| Produced by | Leanna Creel Andrea Sperling |

| Screenplay by | Brian Wayne Peterson |

| Story by | Jamie Babbit |

| Starring | Natasha Lyonne Cathy Moriarty RuPaul Charles Clea DuVall |

| Music by | Pat Irwin |

| Cinematography | Jules Labarthe |

| Editing by | Cecily Rhett |

| Distributed by | Lions Gate Films The Kushner-Locke Company |

| Release date(s) | Toronto Film Festival: September 12, 1999 United States: July 7, 2000 Australia: November 16, 2000 United Kingdom: April 13, 2001 |

| Running time | 85 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$1,000,000 |

| Gross revenue | US$2,595,216 (worldwide) |

But I'm a Cheerleader is a 1999 satirical romantic comedy film directed by Jamie Babbit and written by Brian Wayne Peterson. Natasha Lyonne stars as Megan Bloomfield, an apparently happy heterosexual high school cheerleader. However, her friends and family are convinced that she is a homosexual and arrange an intervention, sending her to a residential inpatient reparative therapy camp to cure her lesbianism. At camp, Megan soon realizes that she is indeed a lesbian and, despite the therapy, gradually comes to embrace this. The supporting cast features Clea DuVall, Cathy Moriarty, RuPaul, Mink Stole and Bud Cort.

But I'm a Cheerleader was Babbit's first feature film. It was inspired by an article about conversion therapy and her childhood familiarity with rehabilitation programs. She used the story of a young woman finding her sexual identity to explore the social construction of gender roles and heteronormativity. The costume and set design of the film highlighted these themes using artificial textures in intense blues and pinks.

When it was initially rated as NC-17 by the MPAA, Babbit made cuts to allow it to be re-rated as R. When interviewed in the documentary film This Film Is Not Yet Rated Babbit criticized the MPAA for discriminating against films with homosexual content. The film was not well received by critics who compared it unfavorably to the films of John Waters and criticized the colorful production design. The lead actors were praised for their performances but some of the characters were described as stereotypical.

Contents |

Plot

Seventeen-year-old Megan (Lyonne) is a sunny high school senior who loves cheerleading and is dating football player boyfriend Jared. She does not enjoy kissing Jared, however, and prefers looking at her fellow cheerleaders. Combined with Megan's interest in vegetarianism and Melissa Etheridge, her family and friends suspect that Megan is in fact a lesbian. With the help of ex-gay Mike (RuPaul), they surprise her with an intervention. Following this confrontation, Megan is sent to True Directions, a reparative therapy camp which uses a five-step program (similar to Alcoholics Anonymous' twelve-step program) to convert its campers to heterosexuality.

At True Directions, Megan meets the founder, strict disciplinarian Mary Brown (Moriarty), Mary's son Rock, and a group of young people trying to "cure" themselves of their homosexuality. With the prompting of Mary and the other campers, Megan reluctantly agrees that she is a lesbian. This fact, at odds with her traditional, religious upbringing, distresses her and she puts every effort into becoming heterosexual. Early on in her stay at True Directions, Megan discovers two of the boys, Dolph and Clayton, making out. She panics and screams, leading to their discovery by Mike. Dolph is made to leave and Clayton is punished by being forced into isolation.

The True Directions program involves the campers admitting their homosexuality, rediscovering their gender identity by performing stereotypically gender-associated tasks, finding the root of their homosexuality, demystifying the opposite sex, and simulating heterosexual intercourse. Over the course of the program, Megan becomes friends with another girl at the camp, a college student named Graham (DuVall) who, though more comfortable being gay than Megan, was forced to the camp at the risk of otherwise being disowned by her family.

The True Directions kids are encouraged to rebel against Mary by two of her former students, ex-ex-gays Larry and Lloyd, who take the campers to a local gay bar where Graham and Megan's relationship develops into a romance. When Mary discovers the outing, she makes them all picket Larry and Lloyd's house, carrying placards and shouting homophobic abuse.

Megan and Graham sneak away one night to have sex and begin to fall in love. When Mary finds out, Megan, now at ease with her sexual identity, is unrepentant. She is made to leave True Directions and, now homeless, goes to stay with Larry and Lloyd. Graham, afraid to defy her father, remains at the camp. Megan and Dolph, who is also living with Larry and Lloyd, plan to win back Graham and Clayton.

Megan and Dolph infiltrate the True Directions graduation ceremony where Dolph easily coaxes Clayton away. Megan entreats Graham to join them as well, but Graham nervously declines. Megan then performs a cheer for Graham and tells her that she loves her, finally winning Graham over. They drive off with Dolph and Clayton. The final scene of the film shows Megan's parents (Stole and Cort) attending a PFLAG meeting to come to terms with their daughter's homosexuality.

Cast and characters

- Natasha Lyonne as Megan Bloomfield. When confronted with evidence of her homosexuality at True Directions, Megan counters "I get good grades, I go to church, I'm a cheerleader".[1]

- Clea DuVall as Graham Eaton, a college student and the daughter of wealthy parents who threaten to disown her if she does not change her sexual orientation. Graham is comfortable with her own sexuality but afraid of living openly as a lesbian.[2]

- Cathy Moriarty as Mary J. Brown, the founder of True Directions. Although it is not mentioned in the film, Babbit's back-story for Mary was that her husband is a homosexual who ran off to San Francisco.[2] As a result it is her life's mission to help young gay people to turn straight. Moriarty describes her character as "Sandra Dee on crack".[3]

- RuPaul as Mike, ex-gay and Mary's right-hand man. Mike tries to teach the boys at True Directions to become more masculine, while wearing a t-shirt that proclaims "Straight is great!"

- Mink Stole as Nancy Bloomfield, Megan's mother. Megan's parents are Christians who want Megan to follow the role in life that they believe God has set for her.

- Bud Cort as Peter Bloomfield, Megan's father.

- Melanie Lynskey as Hilary Vandermuller who adheres closely to the rules of True Directions and graduates.

- Joel Michaely as Joel Goldberg a young Jewish man who desperately wants to be straight and eventually graduates from True Directions.

- Kip Pardue as Clayton Dunn, a quiet young man who works in retail.

- Katharine Towne as Sinead Laren, a goth girl who says she likes pain. Sinead is attracted to Graham and is later jealous of Graham's relationship with Megan. Despite this, Sinead graduates from True Directions.

- Douglas Spain as Andre, who describes himself as "actor, dancer, homosexual".[1] He fails to convince Mary of his heterosexuality and is asked to leave True Directions before graduation.

- Eddie Cibrian as Rock Brown, Mary's muscular but henpecked son. Rock works as a handy man at True Directions and although supposedly straight appears to lust after Mike.[4]

- Dante Basco as Dolph, a varsity wrestler who begins a relationship with Clayton. Dolph is then kicked out of True Directions and goes to live with Larry and Lloyd Morgan-Gordon.

- Katrina Phillips as Jan, a softball player who has been sent to True Directions due to her butch appearance and mannerisms. Jan eventually realizes that she was never a lesbian, but always thought she was because others assumed she was. She leaves True Directions.

- Richard Moll as Larry Morgan-Gordon, ex-ex-gay and one of Mary's former students who runs what Megan calls the "underground homo railroad"[1] with his partner Lloyd. They try to give True Directions campers an alternative view point on homosexuality with trips to the local gay bar. Babbit based the characters of Larry and Lloyd on ex-ex-gays Michael Bussee and Gary Cooper formerly of Exodus International.[5]

- Julie Delpy as a lipstick lesbian who Megan meets and dances with at a gay bar.

- Wesley Mann as Lloyd Morgan-Gordon, ex-ex-gay and partner of Larry.

- Brandt Wille as Jared, Megan's football-playing boyfriend.

- Michelle Williams as Kimberly, head cheerleader and Megan's schoolfriend. Kimberly suspects Megan of being a lesbian and participates in her intervention.

- Ione Skye as Kelly, reformed lesbian in True Directions promotional video.

Background and production

But I'm a Cheerleader was Babbit's first feature film.[6] She had previously directed two short films, Frog Crossing (1996) and Sleeping Beauties (1999), both of which were shown at the Sundance Film Festival. She went on to direct the 2005 thriller The Quiet and the 2007 comedy Itty Bitty Titty Committee. Babbit and Sperling (as producer) secured financing from Michael Burns, then the vice president of Prudential Insurance (now Vice Chairman of Lions Gate Entertainment) after showing him the script at Sundance.[6][7] According to Babbit, their one-sentence pitch was "Two high-school girls fall in love at a reparative therapy camp".[8] Burns gave them an initial budget of US$500,000 which was increased to US$1 million when the film went into production.[7]

Conception

Babbit, whose mother runs a halfway house called New Directions for young people with drug and alcohol problems, had wanted to make a comedy about rehabilitation and the 12-step program.[8] After reading an article about a man who had returned from a reparative therapy camp hating himself, she decided to combine the two ideas.[3][7] With girlfriend Andrea Sperling, she came up with the idea for a feature film about a cheerleader who attends a reparative therapy camp.[9] They wanted the main character to be a cheerleader because it is "...the pinnacle of the American dream, and the American dream of femininity".[2] Babbit wanted the film to represent the lesbian experience from the femme perspective to contrast with several films of the time that represented the butch perspective (for example, Go Fish and The Watermelon Woman).[7] She also wanted to satirize both the religious right and the gay community.[9] Not feeling qualified to write the script herself, Babbit brought in screenwriter and recent graduate of USC School of Cinematic Arts Brian Wayne Peterson.[2][9] Peterson had experience with reparative therapy while working at a prison clinic for sex offenders.[8] He has said that he wanted to make a film that would not only entertain people, but also make people get angry and talk about the issues it raised.[8]

Set and costume design

Babbit says that her influences for the look and feel of the film included John Waters, David LaChapelle, Edward Scissorhands and Barbie.[9] She wanted the production and costume design to reflect the themes of the story. There is a progression from the organic world of Megan's hometown, where the dominant colors are orange and brown, to the fake world of True Directions, dominated by intense blues and pinks (which are intended to show the artificiality of gender construction).[9] According to Babbit, the germaphobic character of Mary Brown represents AIDS paranoia and her clean, ordered world is filled with plastic flowers, fake sky and PVC outfits.[9] The external shots of the colorful house complete with a bright pink picket fence were filmed in Palmdale, California.[8]

Casting

Babbit recruited Clea DuVall, who had starred in her short film Sleeping Beauties to play the role of Graham Eaton. Babbit says that she was able to get a lot of the cast through DuVall including Natasha Lyonne and Melanie Lynskey.[6] Lyonne first saw the script in the back of DuVall's car and subsequently contacted her agent about it.[8] She had seen and enjoyed Babbit's short Sleeping Beauties and was eager to work with the director.[5] She was not the first choice for the role of Megan. An unnamed actress wanted to play the part but eventually turned it down because she was too Christian and did not want her family to see her face on the poster.[6] Babbit briefly considered Rosario Dawson as Megan but her executive producer persuaded her that Dawson, who is Hispanic, would not be right for the All-American character.[9]

Babbit made a conscious effort to cast people of color for minor roles, in an effort to combat what she describes as "racism at every level of making movies".[9] From the beginning she intended the characters of Mike (played by RuPaul), Dolph (Dante Basco) and Andre (Douglas Spain) to be African American, Asian and Hispanic, respectively. She initially considered Arsenio Hall for the character of Mike but says that Hall was uncomfortable about playing a gay-themed role.[2] As Mike, RuPaul makes a rare film appearance out of drag.[10]

Themes

But I'm a Cheerleader is not only about sexuality, but also gender and the social construction of gender roles.[11] One of the ways in which Babbit highlighted what she called the artificiality of gender construction was by using intense blues and pinks in her production and costume design.[9] Chris Holmlund in Contemporary American Independent Film notes this feature of the film and calls the costumes "gender-tuned".[12] Ted Gideonse in Out magazine wrote that the costumes and colors of the film show how false the goals of True Directions are.[8]

Gender roles are further reinforced by the tasks the campers have to perform in "Step 2: Rediscovering Your Gender Identity". Nikki Sullivan in A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory says that this rediscovery is shown to be difficult and unsuccessful rather than the natural discovery of their latent heterosexuality.[11] Sullivan says that the film not only highlights the ways in which gender and sexuality are constructed but also takes the norms and truths about heteronormative society and renders them strange or "queer".[11] Holmlund says that Babbit makes the straight characters less normal and less likable than the gay ones.[12] Sullivan says that this challenge of heteronormativity makes But I'm a Cheerleader an exemplification of queer theory.[11]

Rating and distribution

When originally submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America rating board, But I'm a Cheerleader received an NC-17 rating. In order to get a commercially-viable R rating, Babbit removed a two second shot of Graham's hand sweeping Megan's clothed body, a camera pan up Megan's body when she is masturbating, and a comment that Megan "ate Graham out" (slang for cunnilingus).[13] Babbit was interviewed by Kirby Dick for his 2006 documentary film This Film Is Not Yet Rated.[14] A critique of the MPAA's rating system, it suggests that films with homosexual content are treated more stringently than those with only heterosexual content, and that scenes of female sexuality draw harsher criticism from the board than those of male sexuality.[15] American Pie (also released in 1999), which features a teenage boy masturbating, was given an R rating. Babbit says that she felt discriminated against for making a gay film.[16] The film was rated as M (for mature audiences) in Australia and in New Zealand, 14A in Canada, 12 in Germany and 15 in the United Kingdom.

The film premiered on September 12, 1999 at the Toronto International Film Festival and was shown in January 2000 at the Sundance Film Festival. It went on to play at several international film festivals including the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras festival and the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. It first appeared in U.S. theaters on July 7, 2000, distributed by Lions Gate Entertainment.[17] Fine Line Features had intended to distribute the film but dropped it two months before it was due to open following a dispute with the film's production company, Ignite Entertainment.[9][18] It closed after 8 weeks, with its widest release having been 115 theaters.[17]

The film was released on Region 1 DVD by Lions Gate on July 22, 2002 and by Universal Studios on October 3, 2002.[19] Other than the theatrical trailer, it contains no extras.[20] It was released on Region 2 DVD on June 2, 2003 by Prism Leisure. In addition to the trailer, it features an interview with Jamie Babbit and behind the scenes footage.[21]

Reception

Box office and audience reaction

But I'm a Cheerleader grossed US$2,205,627 in the United States and US$389,589 elsewhere, giving a total of US$2,595,216 worldwide. In its opening weekend, showing at four theaters, it earned $60,410 which was 2.7% of its total gross.[17] According to Box Office Mojo, it ranked at 174 for all films released in the US in 2000 and 74 for R-rated films released that year. As of March 2010[update], its all time box-office ranking for LGBT-related films is 70.[22]

The film was a hit with festival audiences and received standing ovations at the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival.[2][23] It has been described as a favorite with gay audiences and on the art house circuit.[24][25]

Critical

Critical response to But I'm a Cheerleader was mostly negative. Rotten Tomatoes gave it a score of 35% based on 43 reviews,[26] and Metacritic gave it a score of 39% based on 30 reviews.[27] The overall theme of reviews is that it is a heartfelt film with good intentions, but that it is flawed.[28][29][30] Some reviewers found it funny and enjoyable with "genuine laughs".[31][32] Roger Ebert called it the type of film that "might eventually become a regular on the midnight cult circuit."[29] Others found it obvious, leaden and heavy handed.[28][33]

Writing for The New York Times, Elvis Mitchell described the character of Megan as a sweet heroine and Lyonne and DuVall were praised for their performances.[33][34] Mick LaSalle called Lyonne wonderful and said that she was well matched by DuVall.[31] Marjorie Baumgarten said that they "hit the right notes".[32] Alexandra Mendenhall, writing for AfterEllen.com felt that the relationship between Graham and Megan, having great chemistry, does not get enough screen time.[35] Mitchell called their love scenes "tender".[33] Other characters, particularly the males, were described as "offputting" and "nothing but stereotypes".[33][34]

Several reviewers compared the film to those of director John Waters but felt that it fell short of the mark.[34] Stephanie Zacharek called it a "Waters knockoff"[28] while Ebert said that Waters might have been ruder and more polished.[29] Babbit says that although Waters is one of her influences, she did not want her film to have the "bite" of his.[9] She states that whereas John Waters does not like romantic comedies, she wanted to tell a conventionally romantic story.[9] The production design, which was important to the overall look and feel of the film,[7] drew mixed responses. LaSalle described it as clever and eyecatching and James Berardinelli called it a standout feature.[30][31] Others found it to be gaudy, dated, cartoonish and ghastly.[9][28]

Stephanie Zacharek, writing for Salon.com said that with regard to issues of sexual orientation and homophobia, Babbit is preaching to the converted.[28] Cynthia Fuchs, for NitrateOnline.com, agreed, stating that "no one who is phobic might recognize himself in the film" and that "the audience who might benefit most from watching it either won't see the film or won't see the point".[36] David Edelstein said that the one sidedness of the film creates a lack of dramatic tension and calls it lazy counterpropaganda.[37] In contrast, LaSalle said that "the picture manages to make a heartfelt statement about the difficulties of growing up gay" and Timothy Shary said that the film openly challenges homophobia and offers support to teenaged gay viewers.[31][38] Chris Holmlund said that the film shows that queer identity is multi-faceted, using as an example the scene where the ex-ex-gays tell Megan that there is no one way to be a lesbian.[12]

Reviews from the gay media were similar to those from the mainstream press. Jan Stuart, writing for The Advocate, said that although the film tries to subvert gay stereotypes, it is unsuccessful. She called it numbingly crude and said that the kitsch portrait of Middle America is out of touch with today's gay teenagers.[39] Mendenhall for AfterEllen.com called the story predictable and the characters stereotypical. Despite these comments she said that overall the film was funny and enjoyable.[35] Curve called the film an incredible comedy and said that with this and her other work, Babbit has redefined lesbian film.[40]

Awards

The film won the Audience Award and the Graine de CinΓ©phage Award at the 2000 CrΓ©teil International Women's Film Festival, an annual French festival which showcases the work of female directors.[41] Also that year it was nominated by the Political Film Society of America for the PFS award in the categories of Human Rights and ExposΓ©, but lost out to The Green Mile and Boys Don't Cry respectively.[42]

Music

The composer for But I'm a Cheerleader was Pat Irwin. The soundtrack has never been released on CD. Artists featured include indie acts Saint Etienne, Dressy Bessy and April March.[43] RuPaul contributed one track, "Party Train," which Eddie Cibrian's character Rock is shown dancing to.

Track listing

- "Chick Habit (Laisse tomber les filles)" (Elinor Blake, Serge Gainsbourg) performed by April March

- "Just Like Henry" (Tammy Ealom, John Hill, Rob Greene, Darren Albert) performed by Dressy Bessy

- "If You Should Try and Kiss Her" (Ealom, Hill, Greene, Albert) performed by Dressy Bessy

- "Trailer Song" (Courtney Holt, Joy Ray) performed by Sissy Bar

- "All or Nothing" (Cris Owen, Miisa) performed by Miisa

- "We're in the City" (Sarah Cracknell, Bob Stanley, Pete Wiggs) performed by Saint Etienne

- "The Swisher" (Dave Moss, Ian Rich) performed by Summer's Eve

- "Funnel of Love" (Kent Westbury, Charlie McCoy) performed by Wanda Jackson

- "Ray of Sunshine" (Go Sailor) performed by Go Sailor

- "Glass Vase Cello Case" (Madigan Shive, Jen Wood) performed by Tattle Tale

- "Party Train" (RuPaul) performed by RuPaul

- "Evening in Paris" (Lois Maffeo) performed by Lois Maffeo

- "Together Forever in Love" (Go Sailor) performed by Go Sailor

Adaptations

In 2005 the New York Musical Theatre Festival featured a musical stage adaptation of But I'm a Cheerleader written by librettist and lyricist Bill Augustin and composer Andrew Abrams. With 18 original songs, it was directed by Daniel Goldstein and starred Chandra Lee Schwartz as Megan. It played during September 2005 at New York's Theatre at St. Clement's.[44]

References

- β 1.0 1.1 1.2 Babbit, Jamie (director). (1999). But I'm a Cheerleader. [Motion picture (DVD)]. Santa Monica, California: Lions Gate Entertainment.

- β 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Grady, Pam. "Rah Rah Rah: Director Jamie Babbit and Company Root for But I'm a Cheerleader". Reel.com. Hollywood Management Company. Archived from the original on May 10, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20050306182317/www.reel.com/reel.asp?node=features/interviews/cheerleader. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- β 3.0 3.1 Stukin, Stacie (July 4, 2000). "But she's serious". The Advocate. Archived from the original on July 4, 2000. http://web.archive.org/web/20071224004310/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1589/is_2000_July_4/ai_63059697

- β Nikki Sullivan goes as far as calling Rock overtly homosexual and says that Mary's desire to cure her son of homosexuality is the inspiration for the True Directions program. Sullivan, Nikki (2003). A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0748615970.

- β 5.0 5.1 Judd, Daniel (October 4, 2000). "Interviews β Jamie Babbit". RainbowNetwork.com. http://www.rainbownetwork.com/Film/detail.asp?iData=9110&iChannel=14&nChannel=Film. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- β 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Warn, Sarah (June 2004). "Interview with Jamie Babbit". AfterEllen.com. http://www.afterellen.com/archive/ellen/People/interviews/62004/jamiebabbit.html. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- β 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Gerald Duchovnay (Ed.) (2004). Film Voices: Interviews from Post Script. State University of New York Press, Albany. pp. 153β165. ISBN 0-7914-6156-4.

- β 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Gideonse, Ted (July 2000). "The New Girls Of Summer". Out: p. 56

- β 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Fuchs, Cynthia (July 21, 2000). "So Many Battles to Fight β Interview with Jamie Babbit". Nitrate Online. http://www.nitrateonline.com/2000/fcheerleader.html. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- β Fine, Marshall. "Ladies' Man: An Interview with Superdiva RuPaul". DrDrew.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071017180115rn_1/www.drdrew.com/DrewLive/article.asp?id=908. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- β 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Sullivan, Nikki (2003). A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 52β56. ISBN 0748615970.

- β 12.0 12.1 12.2 Holmlund, Chris (2004). Contemporary American Independent Film: From The Margins To The Mainstream. Routledge. pp. 183β187. ISBN 0415254868.

- β Taubin, A. (August 3, 1999). "Erasure Police". The Village Voice: p. 57

- β Dick, Kirby (director). (2006). This Film Is Not Yet Rated. [Motion picture (DVD)]. New York, NY: IFC Films.

- β Carlson, Daniel (2006). "Muscles and Boobies and Wieners, Oh No". Pajiba.com. http://www.pajiba.com/this-film-is-not-yet-rated.htm. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- β "'This Film is Not Yet Rated' Explores Anti-Gay Bias of MPAA Ratings System". GayWired.com. September 1, 2006. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080222041920/http://www.gaywired.com/article.cfm?section=9&id=10452. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- β 17.0 17.1 17.2 "But I'm a Cheerleader". BoxOfficeMojo.com. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?page=main&id=butimacheerleader.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- β Churi, Maya; Eugene Hernandez (June 3, 2000). "Lion's Gate acquires Jamie Babbit's "But I'm A Cheerleader"". IndieWIRE. http://www.indiewire.com/article/daily_news_lions_gate_gets_cheerleader_lipskys_at_lot_47_ifpwest_joins_laif/. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- β "But I'm a Cheerleader". MovieWeb.com. http://www.movieweb.com/dvd/DVdX0eilBNtogj. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- β "DVD Review β Quick Peeks". DVD Review. http://www.dvdreview.com/quickpeek/collect/254.shtml. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- β "But I'm a Cheerleader". Amazon.co.uk. http://www.amazon.co.uk/But-Im-Cheerleader-Natasha-Lyonne/dp/B00005NBUC. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- β "Gay / Lesbian Movies". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/genres/chart/?id=gay.htm. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- β Mandelberger, Sandy. "New York Lesbian And Gay Film Festival -- 1β11 June". FilmFestivals.com. http://www.filmfestivals.com/int/overviews/2000/NYgay_00.htm. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- β Tropiano, Stephen. "But I'm a Cheerleader Review". PopMatters. http://www.popmatters.com/pm/film/reviews/34400/but-im-a-cheerleader/. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- β Benshoff, Harry M.; Sean Griffin (2004). America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies. Blackwell Publishing. p. 333. ISBN 0631225838.

- β "But I'm a Cheerleader". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/but_im_a_cheerleader/. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- β "But I'm a Cheerleader". MetaCritic. http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/butimacheerleader?q=but%20i'm%20a%20cheerleader. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- β 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Zacharek, Stephanie (July 7, 2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader". Salon.com. http://archive.salon.com/ent/movies/review/2000/07/07/cheerleader/index.html. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- β 29.0 29.1 29.2 Ebert, Roger (July 14, 2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20000714/REVIEWS/7140302/1023. Retrieved April 29, 2007

- β 30.0 30.1 Berardinelli, James (2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader". ReelViews.net. http://www.reelviews.net/movies/b/but_cheerleader.html. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- β 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 LaSalle, Mick; Guthmann, Edward (July 7, 2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2000/07/07/DD85029.DTL#cheerleader. Retrieved April 29, 2007

- β 32.0 32.1 Baumgarten, Marjorie (July 28, 2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader". The Austin Chronicle. http://www.austinchronicle.com/gyrobase/Calendar/Film?Film=oid%3a140561. Retrieved April 29, 2007

- β 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Mitchell, Elvis (July 7, 2000). "Don't Worry. Pink Outfits Will Straighten Her Out.". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/library/film/070700cheer-film-review.html. Retrieved April 29, 2007

- β 34.0 34.1 34.2 Noh, David. "But I'm a Cheerleader". Film Journal International. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070926232311/http://www.filmjournal.com/filmjournal/reviews/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1000697322. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- β 35.0 35.1 Mendenhall, Alexandra (September 1, 2006). "Review of "But I'm a Cheerleader"". AfterEllen.com. http://www.afterellen.com/Movies/2006/9/cheerleader.html. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- β Fuchs, Cynthia (July 28, 2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader". Nitrate Online. http://www.nitrateonline.com/2000/rcheerleader.html. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- β Edelstein, David (July 7, 2000). "Overwrought caricatures backfire in But I'm a Cheerleader". Slate. http://www.slate.com/id/85778. Retrieved November 4, 2007

- β Shary, Timothy (2005). Teen Movies: American Youth on Screen. Wallflower Press. p. 99. ISBN 1904764495. http://books.google.com/?id=howIB0OrsUYC&pg=PA99.

- β Stuart, Jan (July 18, 2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader. - Review". The Advocate. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080120182946/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1589/is_2000_July_18/ai_63398442

- β "Women to watch in film". Curve: p. 22. November 2003

- β Sullivan, Monica (2000). "But I'm a Cheerleader-- Jamie Babbit Wins CrΓ©teil Films de Femmes 'Prix du Public'". Movie Magazine International. http://www.shoestring.org/mmi_revs/but-im-a-cheerleader.html. Retrieved May 26, 2007

- β "Political Film Society β Previous Award Winners". Political Film Society. http://www.geocities.com/~polfilms/previous.html. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- β "Soundtrack Details: But I'm a Cheerleader". SoundtrackCollector. http://www.soundtrackcollector.com/catalog/soundtrackdetail.php?movieid=75068. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- β "But I'm A Cheerleader To Debut At NYMF With Chandra Lee Schwartz, Kelly Karbacz, Natalie Joy Johnson, John Hill And More". BroadwayWorld.com. August 25, 2005. http://www.broadwayworld.com/viewcolumn.cfm?colid=4553. Retrieved October 14, 2007.