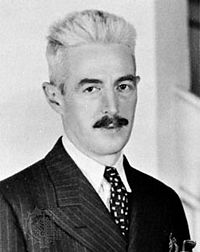

Dashiell Hammett

| Dashiell Hammett | |

|---|---|

Dashiell Hammett |

|

| Born | Samuel Dashiell Hammett May 27, 1894 Saint Mary's County, Maryland, United States |

| Died | January 10, 1961 (aged 66) New York City, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1929–1951 |

| Genres | Hardboiled crime fiction, detective fiction |

|

Influenced

Raymond Chandler, Chester Himes, Mickey Spillane, Ross Macdonald, John D. MacDonald, William S. Burroughs, Robert B. Parker, Sara Paretsky, Lawrence Block, James Ellroy, Sue Grafton, Walter Mosley, William Gibson, Rian Johnson, Richard K. Morgan, Robert Crais

|

|

Samuel Dashiell Hammett (pronounced /dəˈʃiːl/; May 27, 1894 – January 10, 1961) was an American author of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. Among the enduring characters he created are Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon), Nick and Nora Charles (The Thin Man), and the Continental Op (Red Harvest and The Dain Curse).

In addition to the significant influence his novels and stories had on film, Hammett "is now widely regarded as one of the finest mystery writers of all time"[1] and was called, in his obituary in The New York Times, "the dean of the... 'hard-boiled' school of detective fiction".[2] Time magazine included Hammett's 1929 novel Red Harvest on a list of the 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005.[3]

Contents |

Early life

Hammett was born on a farm called Hopewell and Aim off Great Mills Road, St. Mary's County, in southern Maryland.[4] His parents were Richard Thomas Hammett and Anne Bond Dashiell. (The Dashiells are an old Maryland family, the name being an Anglicization of the French De Chiel). He was baptized a Roman Catholic[5] and grew up in Philadelphia and Baltimore. "Sam," as he was known before he began writing, left school when he was 13 years old and held several jobs before working for the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. He served as an operative for the Pinkertons from 1915 to February 1922, with time off to serve in World War I. However, the agency's role in union strike-breaking eventually disillusioned him.[6]

During the war, Hammett enlisted in the United States Army and served in the Motor Ambulance Corps. However, he became ill with the Spanish flu and later contracted tuberculosis. He spent the war as a patient in Cushman Hospital, Tacoma, Washington. While hospitalized he met and married a nurse, Josephine Dolan, and had two daughters, Mary Jane (1921-10-15) and Josephine (1926).[7] Shortly after the birth of their second child, Health Services nurses informed Josephine that due to Hammett's tuberculosis, she and the children should not live with him. So they rented a place in San Francisco. Hammett would visit on weekends, but the marriage soon fell apart. Hammett still supported his wife and daughters financially with the income he made from his writing.[8]

Hammett turned to drinking, advertising, and, eventually, writing. His work at the detective agency provided him the inspiration for his writings.[9]

Career

Hammett was known for his authenticity and realism. He drew on his experiences as a Pinkerton operative. As Hammett said: "All my characters were based on people I've known personally, or known about." In The Simple Art of Murder, Hammett's successor in the field, Raymond Chandler, summarized Hammett's accomplishments:

Hammett was the ace performer... He is said to have lacked heart; yet the story he himself thought the most of [The Glass Key] is the record of a man's devotion to a friend. He was spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.

Later years

From 1929 to 1930 Dashiell was romantically involved with Nell Martin, an author of short stories and several novels. He dedicated The Glass Key to her, and in turn, she dedicated her novel Lovers Should Marry to Hammett.

In 1931, Hammett embarked on a 30-year affair with playwright Lillian Hellman. This relationship was portrayed in the film Julia, in which Hammett was portrayed by Jason Robards and Hellman by Jane Fonda, in Oscar winning and nominated performances respectively.

He wrote his final novel in 1934, and devoted much of the rest of his life to left-wing activism. He was a strong anti-fascist throughout the 1930s and in 1937 he joined the American Communist Party.[10] As a member of the League of American Writers, he served on its Keep America Out of War Committee in January 1940 during the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact.[11]

Service in World War II

In 1942, after Pearl Harbor, Hammett enlisted in the United States Army. Though he was a disabled veteran of World War I, and a victim of tuberculosis, he pulled strings in order to be admitted to the service. He spent most of World War II as an Army sergeant in the Aleutian Islands, where he edited an Army newspaper. He came out of the war suffering from emphysema. As a corporal in 1943, he co-authored The Battle of the Aleutians with Cpl. Robert Colodny under the direction of Infantry Intelligence Officer Major Henry W. Hall.

Post-war political activity

After the war, Hammett returned to political activism, "but he played that role with less fervor than before."[12] He was elected President of the Civil Rights Congress of New York on June 5, 1946 at a meeting held at the Hotel Diplomat in New York City, and "devoted the largest portion of his working time to CRC activities."[12] In 1946, a bail fund was created by the CRC "to be used at the discretion of three trustees to gain the release of defendants arrested for political reasons."[13] Those three trustees were Hammett, who was chairman, Robert W. Dunn, and Frederick Vanderbilt Field, "millionaire Communist supporter."[13] On April 3, 1947, the CRC was designated a Communist front group on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations, as directed by U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s Executive Order 9835.[14]

Imprisonment and the blacklist

The CRC's bail fund gained national attention on November 4, 1949, when bail in the amount of "$260,000 in negotiable government bonds" was posted "to free eleven men appealing their convictions under the Smith Act for criminal conspiracy to teach and advocate the overthrow of the United States government by force and violence."[13] On July 2, 1951, their appeals exhausted, four of the convicted men fled rather than surrender themselves to Federal agents and begin serving their sentences. At that time, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York issued subpoenas to the trustees of the CRC bail fund in an attempt to learn the whereabouts of the fugitives.[13] Hammett testified on July 9, 1951 in front of United States District Court Judge Sylvester Ryan, facing questioning by Irving Saypol, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, described by Time as "the nation's number one legal hunter of top Communists".[13] During the hearing Hammett refused to provide the information the government wanted, specifically, the list of contributors to the bail fund, "people who might be sympathetic enough to harbor the fugitives."[13] Instead, on every question regarding the CRC or the bail fund, Hammett took the Fifth Amendment, refusing to even identify his signature or initials on CRC documents the government had subpoenaed. As soon as his testimony concluded, Hammett was immediately found guilty of contempt of court.[13][15][16][17]

During the 1950s he was investigated by Congress (see McCarthyism), and testified on March 26, 1953 before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Although he testified to his own activities, he refused to cooperate with the committee and was blacklisted.

Death

On January 10, 1961, Hammett died in New York City's Lenox Hill Hospital, of lung cancer, diagnosed just two months before. As a veteran of two World Wars, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

In literature

Fellow crime writer and former San Francisco detective Joe Gores wrote a novel in 1975 entitled Hammett, which imagines Hammett himself being drawn back to the work of a private eye in order to honor a debt to his mentor. The novel was adapted into the film Hammett (1982), which was produced by Francis Ford Coppola and directed by Wim Wenders. In the film, Frederic Forrest plays Hammett. Forrest also played Hammett in the TV film Citizen Cohn (1992).

Gores also recently wrote Spade & Archer (2009), a prequel to The Maltese Falcon. The novel investigates in richer detail the back stories of Sam Spade, his partner Miles Archer, and other characters from the original story. Gores was able to secure permission from Jo Marshall, Hammett's daughter, and Julie Rivett, Marshall's daughter and Hammett's granddaughter, to write the book. Although Marshall first refused, the Hammett family later changed their mind because they felt that Gores was the right person to tell the story, primarily because he was a crime writer and a former San Francisco private investigator, just like Hammett. According to Rivett, "[Gores] walked the walk as well as he talked the talk. He knows as well as anyone where those characters came from."[18]

In Laurie R. King's Locked Rooms, Hammett assists Sherlock Holmes and Mary Russell in solving a mystery from Russell's childhood.

Works

Novels

- Red Harvest (published on February 1, 1929)

- The Dain Curse (July 19, 1929)

- The Maltese Falcon (February 14, 1930)

- The Glass Key (April 24, 1931)

- The Thin Man (January 8, 1934)

Collected short fiction

- $106,000 Blood Money (Bestseller Mystery, 1943) A paperback digest that collects two connected Op stories, The Big Knockover and $106,000 Blood Money.

- Blood Money (Tower, 1943) The hardcover edition of the Bestseller Mystery title.

- The Adventures of Sam Spade (Bestseller Mystery, 1944). Paperback digest that collects the three Spade stories and four others. This and the following eight digest collections were compiled and edited by Fred Dannay (one-half of Ellery Queen) with Hammett's permission. All of these were reprinted as dell map-back paperbacks).

- The Continental Op (Bestseller Mystery, 1945) Paperback digest that collects four Op stories.

- The Adventures of Sam Spade (Tower, 1945). The hardcover edition of the digest of the same title—this was the last time the digests were reprinted in hardcover.

- The Return of the Continental Op (The Jonathan Press, 1945). Paperback digest that collects five further Op stories).

- Hammett Homicides (Bestseller Mysteries, 1946). Paperback digest that collects six stories, including four that feature the Op.

- Dead Yellow Women (The Jonathan Press, 1947). Paperback digest that collects six stories, including four that feature the Op.

- Nightmare Town (American Mercury, 1948). Paperback digest that collects four stories, two of which feature the Op.

- The Creeping Siamese (American Mercury, 1950). Paperback digest that collects six stories, three of which feature the Op.

- Woman in the Dark (The Jonathan Press, 1951). Paperback digest that collects six stories, including three that feature the Op, and the three-part novelette Woman in the Dark.

- A Man Named Thin (Mercury Mystery, 1962). The last paperback digest, collects eight stories, including one Op story.

- The Big Knockover (Random House, 1966; an important collection, edited by Lillian Hellman, that helped revive Hammett's literary reputation; includes the unfinished novel Tulip).

- The Continental Op (Random House, 1974; edited by Steven Marcus).

- Woman in the Dark (Knopf, 1988; hardcover edition that collects the three parts of the title novelette; introduction by Robert B. Parker).

- Nightmare Town (Knopf, 1999; hardcover collection, contents different from the digest title of the same name).

- Lost Stories (Vince Emery Productions, 2005; collects 21 stories that have not been collected previously in hardcover or, in several cases, ever. Emery provides several long commentaries on Hammett's career that provide context for the stories; introduction by Joe Gores).

Uncollected stories

- The Diamond Wager (Detective Fiction Weekly, October 19, 1929).

- On the Way (Harper's Bazaar, March 1932).

Other publications

- Creeps by Night; Chills and Thrills (John Day, 1931; Anthology edited by Hammett)[19]

- Secret Agent X-9 Book 1 (David McKay, 1934; collection of the comic strip written by Hammett and illustrated by Alex Raymond)

- Secret Agent X-9 Book 2 (David McKay, 1934; a second collection of the comic strip).

- The Battle of the Aleutians (Field Force Headquarters, Adak, Alaska, 1944; text written by Hammett, with illustrations by Robert Colodny).

- Watch on the Rhine (screenplay of Hellman's play, in Best Film Plays 1943-44, Crown, 1945; also includes the screenplay for Casablanca).

Published as

- Complete Novels (Steven Marcus, ed.) (Library of America, 1999) ISBN 978-1-88301167-3.

- Crime Stories and Other Writings (Steven Marcus, ed.) (Library of America, 2001) ISBN 978-1-93108200-6.

Quotes

| “ | [Hammett] took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley... [He] gave murder back to the kind of people who do it for a reason, not just to provide a corpse; and with means at hand, not with hand wrought dueling pistols, curare, and tropical fish. | ” |

|

— Raymond Chandler, in The Simple Art of Murder

|

| “ | I have been asked many times over the years why he did not write another novel after The Thin Man. I do not know. I think, but I only think, I know a few of the reasons: he wanted to do a new kind of work; he was sick for many of those years and getting sicker. But he kept his work, and his plans for work, in angry privacy and even I would not have been answered if I had ever asked, and maybe because I never asked is why I was with him until the last day of his life. | ” |

|

— Lillian Hellman, in an introduction to a compilation of Hammett's five novels

|

See also

References

- ↑ Layman, Richard (1981). Shadow Man: The Life of Dashiell Hammett. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 239. ISBN 0-15-181459-7.

- ↑ Layman, Richard & Bruccoli, Matthew J. (2002). Hardboiled Mystery Writers: A Literary Reference. Carroll & Graf. pp. 225. ISBN 0-7867-1029-2.

- ↑ Lev Grossman; Richard Lacayo (2005-10-31). "TIME's Critics pick the 100 Best Novels 1923 to the Present". Time. http://www.time.com/time/2005/100books/. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ↑ Shoemaker, Sandy. Tobacco to Tomcats: St. Mary's County since the Revolution. StreamLine Enterprises, Leonardtown, Maryland. pp. 160. http://www.somd.lib.md.us/tobacco_to_tomcats/. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ Gores, Joe in Emery, Vince, editor, Dashiell Hammett: Lost Stories. San Francisco: Vince Emery Productions, 2005, p. 197.

- ↑ Thomas Heise, "'Going blood-simple like the natives': Contagious Urban Spaces and Modern Power in Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest", Modern Fiction Studies 51, no. 3 (Fall 2005) 506.

- ↑ Layman, Richard with Rivett, Julie M. (2001). Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett 1921-1960. Retrieved on 2009-06-02 from http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/h/hammett-01letters.html.

- ↑ Gores in Emery, editor, p. 240 and 336.

- ↑ Gores in Emery, editor, pp. 18-24.

- ↑ FAQ at the CPUSA site

- ↑ Franklin Folsom, Days of Anger, Days of Hope, University Press of Colorado, 1994, ISBN 0870813323

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Layman, Richard (1981). Shadow Man: The Life of Dashiell Hammett. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 206. ISBN 0-15-181459-7.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Shadow Man: The Life of Dashiell Hammett, pp. 219-223

- ↑ Enid Nemy (February 7, 2000). "Frederick Vanderbilt Field, Wealthy Leftist, Dies at 94". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C04E0D9163EF934A35751C0A9669C8B63&n=Top/Reference/Times%20Topics/People/N/Nemy,%20Enid. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ↑ Metress, Christopher (1994). The Critical Response to Dashiell Hammett. Greenwood Press.

- ↑ Johnson, Diane (1983). Dashiell Hammett, a Life. Random House.

- ↑ Petri Liukkonen. "Dashiell Hammett". Books and Writers. http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/dhammett.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ↑ Kara Platoni, Stanford Magazine, "Sleuth or Dare: How Joe Gores recreated Sam Spade", [1]

- ↑ Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers. pp. 140.

Bibliography

- Mundell, EH, A List of the Original Appearances of Dashiell Hammett's Magazine Work, 1968, The Kent State University, Ohio.

- Layman, Richard Dashiell Hammett: A Descriptive Bibliography", 1979 Pittsburgh Series in Bibliography, University of Pittsburgh Press

Biography/criticism/reference

- Nolan, William F. Dashiell Hammett: A Casebook, 1969, McNally & Lofin, Santa Barbara.

- Layman, Richard. Shadow Man: The Life of Dashiell Hammett, 1981, Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, New York

- Nolan, William F. Hammett: A Life at the Edge, 1983, Congdon & Weed, New York.

- Johnson, Diane. Dashiell Hammett: A Life, 1983, Random House, New York.

- Symons, Julian. Dashiell Hammett, 1985, Harcourt, Brace & Javonovich, New York.

- Mellon, Joan. Hellman and Hammett, 1996, Harper Collins, New York.

- Hammett, Jo, A Daughter Remembers, 2001, Carroll and Graf Publishers.

- Lillian Hellman's three volumes of memoir, An Unfinished Woman, Pentimento, and Scoundrel Time contain much Hammett-related material.

External links

- CLUES: A Journal of Detection 23.2 (winter 2005). Guest ed. Richard Layman. Theme issue on Dashiell Hammett

- The Apartment of Dashiell Hammett and Sam Spade

- Library of Congress lecture by Hammett estate trustee and biographer Richard Layman on the 75th anniversary of The Maltese Falcon

- Checklist of where every Hammett story appeared

- PBS American Masters portrait of Hammett

- Dashiell Hammett Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- The Case of Dashiell Hammett (KQED-TV, San Francisco, 1982). Written and produced by Stephen Talbot. Winner of Peabody Award and a special Edgar Allan Poe Award from the Mystery Writers of America.

|

|||||||||||