Eduard Streltsov

|

|||

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Eduard Anatoliyevich Streltsov[1] | ||

| Date of birth | 21 July 1937[1] | ||

| Place of birth | Perovo, Russian SFSR, USSR[1] | ||

| Date of death | 22 July 1990 (aged 53)[1] | ||

| Place of death | Moscow, Russian SFSR, USSR[1] | ||

| Height | 1.82 m (5 ft 11 1⁄2 in) | ||

| Playing position | Forward | ||

| Youth career | |||

| 1950–1953 | Fraser | ||

| Senior career* | |||

| Years | Team | Apps† | (Gls)† |

| 1953–1958 | Torpedo Moscow | 89 | (48) |

| 1965–1970 | Torpedo Moscow | 133 | (51) |

| Total: | 222 | (99) | |

| National team | |||

| 1955–1958 | USSR | 21 | (18) |

| 1966–1968 | USSR | 17 | (7) |

| Total: | 38 | (25) | |

| * Senior club appearances and goals counted for the domestic league only. † Appearances (Goals). |

|||

| Olympic medal record | ||

| Men's Football | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gold | 1956 Melbourne | Team competition |

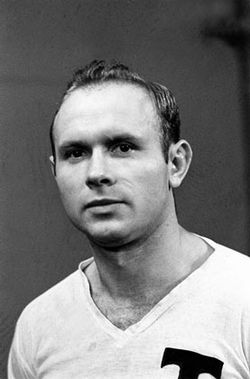

Eduard Anatoliyevich Streltsov (Russian: Эдуард Анатольевич Стрельцов) (21 July 1937 – 22 July 1990) was a Soviet international association football player who, at club level, represented Torpedo Moscow as a forward. Nicknamed "the Russian Pelé", described by Soviet football writer Aleksandr Nilin as "[t]he boy [who] came to us from the land of wonder", and called "the greatest outfield player Russia has ever produced" by British journalist Jonathan Wilson, Streltsov's promising career was interrupted at the age of 20 by a conviction of rape that saw him imprisoned for five years.

After making his debut for the Soviet national team in 1955 at the age of 17, Streltsov played a key role in winning the gold medal for the Soviet Union at the Melbourne Summer Olympics a year later. Latterly described by Wilson as "a tall, powerful forward, possessed of a fine first touch and extraordinary footballing intelligence", he gained the seventh highest number of votes, 12, in the 1957 Ballon d'Or.

Streltsov was accused of raping a 20-year-old woman, Marina Lebedeva, in 1958. Although the evidence against him was "confused and contradictory", Streltsov confessed to the crime, allegedly after being told that doing so would allow him to participate in the 1958 World Cup. Sentenced to twelve years in the labour camps, Streltsov was released after five years and made a return to football two years later, once again appearing for Torpedo Moscow. At the end of his first season back, Torpedo won the Soviet championship, a feat that the club had only accomplished once before. He went on to return to the Soviet national team in 1966, win the Soviet Cup with his club two years later, and be named the Soviet Footballer of the Year in 1967 and in 1968.

After retiring in 1970, Streltsov died in Moscow in July 1990. Six years later, Torpedo renamed their home ground in his honour; the following year, the Russian Football Union named the highest individual honour in Russian football after him. After a statue of Streltsov was erected at the Luzhniki Olympic Complex in 1998, 1999 saw Torpedo build a monument to the former player outside the stadium bearing his name.

Contents |

Early life

Eduard Anatoliyevich Streltsov was born in Perovo, a suburb of Moscow, on 21 July 1937, the son of Anatoly Streltsov, a front-line soldier and reconnaissance officer, and Sofia Frolovna.[1] Anatoly did not return to the family following the Second World War, instead choosing to settle alone in Kiev; Sofia therefore raised her son on her own, working as a metal worker at the Fraser Cutting Instruments Factory in Moscow to support Eduard and herself.[1] As a result, Streltsov had a modest upbringing; "the only pleasure, the only beam of light among the grey weekdays was football".[1] The young Streltsov supported Spartak Moscow.[1]

The factory recognised his talent from a young age: Streltsov became the Fraser Factory football team's youngest ever player when he was 13 years old.[1] He had been representing Fraser for three years when in 1953 a friendly match was organised between Fraser and a youth team from Torpedo Moscow.[1] Streltsov befriended the Torpedo coach, Vasily Provornov, and subsequently left Fraser for Torpedo at the age of 16.[1]

Playing career

Early career

Streltsov was still 16 when he made his debut for Torpedo,[1] and appeared in every league game played by the club during his first season, 1954, scoring four goals.[2] The team finished ninth in the league,[3] a drop from third the previous year.[3] In his second season, 1955, Streltsov was the Soviet top-flight's most prolific goalscorer, playing in all 22 league matches and scoring 15 goals as his side rose to fourth place.[2][3][4] Streltsov was called up to the Soviet national team for the first time in June 1955, halfway through this season, for his first international appearance; a friendly match against Sweden in Stockholm on the 26th of that month.[5] The 17-year-old marked his international debut with a hat-trick within the first 45 minutes as Sweden were despatched 6–0 by the Soviets.[5] Streltsov was picked again later that year for his first international match on home soil, a friendly against India, and once again scored three goals.[5] A further international appearance in Hungary and goal against France meant that by the start of 1956, Streltsov had scored seven goals for the Soviet Union in only four matches.[5] After scoring again in a friendly against Denmark in April 1956,[5] he missed three international matches before returning in September with a goal after three minutes in a 2–1 away victory over West Germany.[5] Streltsov then appeared in two successive defeats for the Soviets,[5] while continuing to score regularly for Torpedo, netting 12 Top League goals during the 1956 season before the Soviet team travelled to the Olympic Games in Melbourne that November.[2][5] Once there, Streltsov scored three in a 16–2 victory over Australia in an unofficial match on 15 November before netting a late winner in the first tournament match against West Germany nine days later.[5] After the Soviets required a replay to overcome Indonesia in the quarter-finals,[5] the team met Bulgaria in the semi-final.[5]

The match finished 0–0 after 90 minutes,[5][7] and with defender Nikolai Tishchenko and Streltsov's fellow Torpedo forward Valentin Ivanov both injured,[7] the Soviet team was "effectively down to nine men" when Bulgaria scored soon into extra time.[7] Streltsov, however, was "magnificent";[7] "dragg[ing] his side forward",[7] he scored an equaliser after 112 minutes and then set up Boris Tatushin of Spartak Moscow four minutes later to score the winning goal.[7] The Soviets were into the final, but Streltsov missed the final against Yugoslavia due to the doctrine of the team's manager, Gavriil Kachalin, that the Soviet forward pairing should also play together at club level.[7] In light of Ivanov's injury, Streltsov was dropped as well; Nikita Simonyan, who took his place, offered Streltsov his gold medal following a 1–0 victory over the Yugoslavs,[5][7] an offer which the Torpedo forward refused with the words "Nikita, I will win many other trophies".[7] Streltsov gained two votes in that year's Ballon d'Or, meaning that at the end of 1956, he was considered by Western European sports journalists to be one of the 24 best players in Europe.[8]

Streltsov returned to the Soviet line-up for the next fixture, a home match against Romania in June 1957 in which he scored his side's goal in a 1–1 draw.[5] Scoring twice more in a 4–0 away win in Bulgaria later that year,[5] he then added another two in a 10–0 victory away against Finland.[5] Streltsov then scored a late winner against Hungary in Budapest in September,[5] and the first goal in a 2–0 win in a World Cup qualifying play-off match in Poland that saw the Soviet Union qualify for the 1958 World Cup.[5] At club level, he scored 12 goals in 15 league matches during the 1957 season as Torpedo,[2] traditionally overshadowed by local rivals such as CSKA, Dynamo and Spartak and never before champions of the USSR,[3][7] finished as runners-up of the Soviet Top League.[3] At the end of the 1957 season, Streltsov came seventh in the 1957 Ballon d'Or, gaining 12 votes;[9] by the start of the World Cup year, 1958, his international record stood at 18 goals in 20 games.[5] Streltsov scored five goals in the first eight league matches of the 1958 Top League season,[2] before appearing in a 1–1 friendly draw with England in Moscow on 18 May 1958.[5]

Conviction of rape

The "[t]alented and good-looking"[7] Streltsov was known for his "womanising"[7] and "liv[ing] the high life",[7] as well as for his "Teddy Boy" haircut.[10] As a key player for both his club team and for the Soviet national side, these traits combined to create the impression in the government psyche that "Streltsov was becoming rather too much of a celebrity".[7] His alleged relationship with Svetlana Furtseva, the 16-year-old daughter of Politburo member Ekaterina Furtseva, brought the problem to a head.[7] With the young Svetlana "apparently besotted" with the Torpedo forward, Furtseva, the first woman ever elected to the Politburo, met the 19-year-old Torpedo forward for the first time at a Kremlin ball held early in 1957 to celebrate the Olympic victory of 1956.[7] Furtseva suggested that he might marry her daughter, to which Streltsov replied "I already have a fiancée and I will not marry her [Svetlana]."[7] He was later heard to remark either "I would never marry that monkey" or "I would rather be hanged than marry such a girl" (both quotes were reported),[7] thus humiliating Furtseva, a minister close to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.[7]

Streltsov was indeed engaged; he had secretly proposed marriage to Alla Demenko before leaving for the Olympics.[11] He married Demenko on 25 February 1957,[11] halfway through preparations for the Soviet season,[11] causing the Department of Soviet Football to criticise both the player and his club over the timing of the ceremony.[7] The Communist Party also seemed to distrust him,[7] considering him a possible defector after he attracted the interest of French and Swedish clubs during tours overseas with Torpedo.[7] His file in the party's archives included the comment: "[a]ccording to a verified source, Streltsov said to his friends in 1957 that he was always sorry to return to the USSR after trips abroad."[7] A week after he had appeared against England for the Soviet national team in a warm-up match in Moscow for the 1958 World Cup, Streltsov was invited to a party by a Soviet military officer, Eduard Karakhanov, to be held on 25 May.[7] Streltsov and the rest of the Soviet squad were on a pre-World Cup training camp at Tarasovka, just outside Moscow, but the team had been given the day as holiday – at the end of these days, the players were meant to report to the authorities at Dynamo Stadium at 4:30 pm,[12] but Streltsov and two team-mates, Spartak players Mikhail Ogonkov and Boris Tatushin, decided to ignore this rule and go to the party anyway.[12] The "drunken"[13] party, held at Karakhanov's dacha,[7] was also attended by a 20-year-old woman named Marina Lebedeva,[7] whom Streltsov had never met.[7] The following morning, Streltsov, Ogonkov and Tatushin were all arrested and charged with raping her.[7]

Nearly everybody at the party had been drunk; the evidence against the married Streltsov, even from Lebedeva, was "confused and contradictory".[13] Despite this, Gavriil Kachalin, the Soviet team coach, was told on attempting to help Streltsov "that Khrushchev himself had been informed about the case";[7] he was then told at a regional Communist Party headquarters that "nothing could be done" owing to influence from above.[7] Kachalin also claimed to have heard that "Furtseva had it in for Streltsov".[7] According to Soviet Union team-mate Nikita Simonyan, the matter of Streltsov raping Lebedeva was not certain;[7] despite stating that "[Streltsov] and the girl slept together",[7] Simonyan claimed that "[i]t was the system that punished Streltsov" and that Streltsov had written to his mother professing his innocence.[7] Seemingly contradicting his words, in Simonyan's possession at the time of his meeting with British journalist Jonathan Wilson in 2006 were photographs of both Lebedeva and of Streltsov from the time of the trial;[7] in one, Lebedeva "was lying back on what seemed to be a hospital bed, apparently asleep, her eyes ringed with bruises",[7] while in another, Streltsov's face "was streaked from nose to cheekbone with three parallel scratches".[7] Valentin Ivanov, Streltsov's team-mate for both Torpedo and for the Soviet Union, said that "I don't know who raped her, but she said it was Streltsov."[7] Streltsov's wife of just over a year, Alla, filed for divorce soon after the accusations were made.[14] Apart from Streltsov himself, the only members of the team present at his trial were Ogonkov and Tatushin, who appeared as witnesses.[14]

About 100,000 workers at Moscow's ZiL car factory, the base of the Torpedo club,[7] planned to march in support of their player,[13] but called this action off when Streltsov confessed to the crime,[13] "apparently after being told that, by doing so, he'd be allowed to play in the [1958] World Cup."[7] Instead, he was sentenced to twelve years in the labour camps,[7][13][15] where he was initially victimised by a young criminal who inflicted upon him so much physical harm that he spent four months in the prison hospital, suffering from injuries caused by blows from either an "iron bar or a shoe heel".[13] Ogonkov and Tatushin, meanwhile, were banned from playing any kind of organised football for three years,[16] and barred from representing the USSR for life.[17] The Soviet team travelled to Sweden without Streltsov, Ogonkov or Tatushin, with the world's press claiming that two teams at the World Cup were severely weakened: England by the Munich air disaster, and the Soviets by the loss of Streltsov.[18] The Soviets reached the quarter-finals, where they lost 2–0 to hosts Sweden;[13] three years before, on Streltsov's international debut, the Soviet Union had won the same fixture 6–0.[5][13] Prison authorities started to produce Streltsov to take part in prison football matches in order to calm down the prisoners in times of trouble;[13] one prisoner, Ivan Lukyanov, later said: "[w]e loved Streltsov, we believed he would return to football. And not only us."[13]

Release and return to football

Streltsov was released on 4 February 1963,[19] five years into his twelve-year sentence, and was allowed to return to football with Torpedo two years later,[13] receiving "a hero's welcome".[10] Despite having lost some of his strength and agility,[13] his footballing intelligence was still intact;[13] with him back in the side, Torpedo won the 1965 Soviet championship,[3][7] with Streltsov scoring 12 goals from 26 league matches.[2] At the end of the season, he came second in the voting for the Soviet Footballer of the Year behind Torpedo team-mate Valery Voronin.[20] It was the second time that Torpedo had won the league; the club had won its first title in 1960, while Streltsov was incarcerated.[3] Streltsov was recalled to the Soviet national team on 16 October 1966 in a home match against Turkey,[21] scoring the first international goal of his comeback a week later in a 2–2 draw with East Germany.[21] An appearance in a 1–0 away defeat against Italy followed two weeks later.[21] Torpedo reached the final of the Soviet Cup in 1966, but lost 2–0 to Dynamo.[3] Streltsov matched his previous seasonal tally of 12 league goals during the 1966 Top League season.[2]

Streltsov successfully re-established himself in the Soviet team over the following year, as he appeared in eight consecutive USSR matches, starting with a 2–0 friendly victory over Scotland in Glasgow in May 1967. He scored two goals during this run in the national side: one each in a 4–2 win against France in Paris on 3 June 1967 and a 4–3 European Championship qualifying home victory over Austria eight days later. After losing his place for the 1968 European Championship qualifying match against Finland on 30 August 1967, Streltsov missed three Soviet Union matches before reclaiming his place for an away friendly match against Bulgaria on 8 October, marking his return with a goal as the Soviets fought back from 1–0 down with 20 minutes left to win 2–1. He retained his place for the rest of the calendar year, and scored a hat-trick away against Chile on 17 December.[21] He was voted Soviet Footballer of the Year at the end of the season,[7][20] although he scored a relatively low six league goals during 1967, his lowest from a full season since his début year of 1954.[2]

Despite this award, Streltsov was dropped from the Soviet team for the first three national team matches of 1968. After featuring in a home friendly win over Belgium in April, he made his final appearance for the USSR in the 2–0 1968 European Championship quarter-final first leg defeat to Hungary on 4 May 1968.[21] The Soviets beat Hungary 3–0 in Moscow a week later, without Streltsov, to qualify for the final tournament on aggregate.[21] Streltsov was left out of the tournament squad, and never played for the USSR again;[21] after his final appearance, his international tally stood at 25 goals in 38 matches.[21] Torpedo won the Soviet Cup during the 1968 season, overcoming Uzbek side Pakhtakor Tashkent 1–0 in the final.[3] Streltsov retained his title of Soviet Footballer of the Year after scoring the highest seasonal total of his career,[7][20] 21 (in the league),[2] and continued to play for Torpedo until 1970, when he retired from football at the age of 33.[1] He failed to score a single goal in any one of the 23 league matches in which he appeared during the 1969 and 1970 seasons, leaving his final league record for Torpedo over both spells standing at 99 goals from 222 games.[2]

Post-retirement

Following a footballing career spent exclusively with Torpedo, Streltsov, a supporter of Spartak, repeatedly complained about his "unrealised dream of donning the red and white jersey of Moscow's most popular club".[1] After his retirement, Torpedo continued to pay his salary in order to fund his study of football coaching at the Institute of Physical Culture.[22] Streltsov returned to Torpedo in the capacity of youth team manager following his qualification;[15] he also spent a brief spell as manager of the first team before returning to the youth team in 1982.[1][15] He also took part in matches contested by former players before dying in 1990 from throat cancer.[1][7] Seven years later, there was a sighting of Marina Lebedeva, the woman Streltsov had confessed to raping, laying flowers at his grave in Moscow on the day after the anniversary of his death.[7]

Due to Olympic policy of the time, the only members of the winning squad who received gold medals were the players who had won the final match; Streltsov did not play in the final, and so was not awarded a medal. He was posthumously given a gold medal in 2006, after this policy was changed retroactively to allow all members of winning Olympic squads to receive medals.[7]

Playing style and legacy

Streltsov is considered by many to be one of the finest footballers ever from either Russia or the Soviet Union – British journalist and author Jonathan Wilson described him as "the greatest outfield player Russia has ever produced",[7] "a tall, powerful forward, possessed of a fine first touch and extraordinary footballing intelligence",[7] while Soviet football writer Aleksandr Nilin referred to him as "[t]he boy [who] came to us from the land of wonder".[13] The back-heeled pass is known in Russia as "Streltsov's pass",[10] and despite the eight-year gap between his two spells as a member of the Soviet national team, Streltsov, nicknamed "The Russian Pelé",[13] was still the fourth highest international goalscorer in the country's history.[23]

Torpedo Moscow's ground, Torpedo Stadium, was redubbed the "Eduard Streltsov Stadium" in 1996;[24] the club subsequently erected a statue of him outside three years later.[25] A sculpture of Streltsov had already been constructed within Moscow's Luzhniki Olympic Complex in 1998.[26] The Russian Football Union had recognised him in 1997, when it introduced the Strelyets prizes as the most prestigious individual honours in Russian football.[27] Annually, managers and coaches across Russia would vote for the best players in each position as well as for the best manager. The Strelyets prizes were discontinued in 2003.[27]

The Streltsov Committee, formed in 2001, was founded in order to attempt to have Streltsov's conviction of rape posthumously overturned in order to clear his name.[13] The campaign's leader, chess champion Anatoly Karpov, claimed in 2001 that "[i]f it hadn't been for that terrible conviction, Streltsov without a doubt would have become the best footballer in the world"[13] and that "[h]e would have been bigger than Pelé".[10] The Central Bank of the Russian Federation paid tribute to Streltsov in 2010, when it minted a commemorative two-ruble coin bearing his likeness. The coin was one of three minted as part of the "Outstanding Sportsmen of Russia" series; the other two pieces bore the faces of footballers Lev Yashin and Konstantin Beskov, respectively.[28]

Honours and achievements

Torpedo Moscow

- Winner

- 1955 Soviet Top League top goalscorer (15 goals from 22 matches)[4]

- 1965 Soviet Top League[3]

- 1967 Soviet Footballer of the Year[20]

- 1968 Soviet Cup[3]

- 1968 Soviet Footballer of the Year[20]

- Runner-up

- Other

- 1956 Ballon d'Or 13th place[7]

- 1957 Ballon d'Or 7th place[7]

USSR national team

- 1955–68: 38 caps, 25 goals[23]

- 1956 Summer Olympics Gold medal[7]

Career statistics

Club performances, by season

- Soviet Top League appearances and goals only; sourced to Журнал «Футбол» (Zhurnal Futbol)[2]

| Club | Season | Appearances | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torpedo Moscow | 1954 | 22 | 4 |

| 1955 | 22 | 15 | |

| 1956 | 22 | 12 | |

| 1957 | 15 | 12 | |

| 1958 | 8 | 5 | |

| Subtotal | 89 | 48 | |

| Incarcerated from 1958 to 1963, returned to football in 1965 |

|||

| 1965 | 26 | 12 | |

| 1966 | 31 | 12 | |

| 1967 | 20 | 6 | |

| 1968 | 33 | 21 | |

| 1969 | 11 | 0 | |

| 1970 | 12 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 133 | 51 | |

| Grand total | 222 | 99 | |

International performances, by calendar year

| National team | Season | Apps | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| USSR | 1955 | 4 | 7 |

| 1956 | 8 | 4 | |

| 1957 | 8 | 7 | |

| 1958 | 1 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 21 | 18 | |

| Incarcerated from 1958 to 1963, returned to football in 1965 |

|||

| 1965 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1966 | 3 | 1 | |

| 1967 | 12 | 6 | |

| 1968 | 2 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 17 | 7 | |

| Grand total | 38 | 25 | |

References

- General

- Kuper, Simon (1998) (in English). Football Against The Enemy. London: Phoenix. ISBN 0753805235.

- Нилин, Александр (Nilin, Aleksandr) (2002) (in Russian). Стрельцов: Человек без локтей. Москва (Moscow): Молодая гвардия (Molodaya Gvardiya). ISBN 5-235-02438-9.

- O'Flynn, Kevin (2001-08-26). "Loyal fans fight to clear name of Russia's Pelé" (in English). The Observer (Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2001/aug/26/theobserver. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- Рыжков, Алексей (Rizhkov, Aleksey) (2008-05-28). "Эдуард Стрельцов: критическая высота полета" (in Russian). Новая (Novaya). http://novaya.com.ua/?/articles/2008/05/28/145008-2. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- Wilson, Jonathan (2006-12-14). "Was Streltsov really the glorious martyr Russian football demands?" (in English). The Guardian (Guardian News and Media). http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/sport/2006/12/14/was_streltsov_really_the_marty.html. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- Specific

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Рыжков (Rizhkov) (2008).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Цыбулько, Валерий (Tsibul'ko, Valeriy). "Эдуард Стрельцов" (in Russian). Журнал «Футбол» (Zhurnal Futbol). http://mag.football.ua/7/v03/01.htm. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Lauzadis, Almantas. "USSR (Soviet Union) - Final Tables 1924-1992" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/tablesu/ussrhist.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cherny, Michael. "Soviet Union/CIS - Record International Players" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/tablesu/ussrtops.html. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 Courtney, Barrie. "Soviet Union - International Results 1952-1959 - Details" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/tablesu/ussr-intres5259.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ Reyes, Macario. "XVI. Olympiad Melbourne 1956 Football Tournament" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/tableso/ol1956f-det.html. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 7.26 7.27 7.28 7.29 7.30 7.31 7.32 7.33 7.34 7.35 7.36 7.37 7.38 7.39 7.40 7.41 7.42 7.43 7.44 7.45 7.46 7.47 7.48 7.49 7.50 7.51 Wilson (2006).

- ↑ Pierrend, José Luis. "European Footballer of the Year ("Ballon d'Or") 1956" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/miscellaneous/europa-poy56.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ Pierrend, José Luis. "European Footballer of the Year ("Ballon d'Or") 1957" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/miscellaneous/europa-poy56.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 White, Jim (2006-04-13). "As Quinn sheds fat, Jones sees fit to play the fool" (in English). The Daily Telegraph (Telegraph Media Group). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/columnists/jimwhite/2335256/As-Quinn-sheds-fat-Jones-sees-fit-to-play-the-fool.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Нилин (Nilin) (2002). pp. 78–79.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Нилин (Nilin) (2002). p. 91.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 O'Flynn (2001).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Нилин (Nilin) (2002). p. 99.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Нилин (Nilin) (2002). p. 251.

- ↑ Ларчиков, Геннадий ((Larchikov, Gennadiy) (2002). "Хyдожник на поле и в жизни" (in Russian). Советский спорт (Sovetskiy Sport) (109).

- ↑ Нилин (Nilin) (2002). p. 93.

- ↑ Kuper (1998). p. 39.

- ↑ Нилин (Nilin) (2002). p. 134.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Movsumov, Rasim. "Soviet Union - Player of the Year Awards" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/miscellaneous/ussrpoy.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 Courtney, Barrie. "Soviet Union - International Results 1960-1969 - Details" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/tablesu/ussr-intres6069.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ Нилин (Nilin) (2002). p. 226.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Mamrud, Roberto. "Soviet Union/CIS - Record International Players" (in English). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. http://www.rsssf.com/miscellaneous/ussr-recintlp.html. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ Wilson, Jonathan (2008-12-23). "Torpedo's traumas suggest the Russian renaissance may be short-lived" (in English). The Guardian (Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/blog/2008/dec/23/torpedo-moscow-jonathan-wilson. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ Ращупкина, Ольга (Rashupkina, Ol'ga) (1999-04-11). "Стрельцов вместо девушки с веслом" (in Russian). Независимая газета. http://www.ng.ru/events/1999-11-04/2_streltsov.html. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ "Памятник Стрельцову" (in Russian). visualrian.ru. РИА Новости (RIA Novosti). http://visualrian.ru/images/item/13356. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Индивидуальные и командные призы" (in Russian). ФК «Зeнит» Санкт-Петербург (FC Zenit St. Petersburg). http://www.fc-zenit.ru/info/page.phtml?id=470114. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ "Commemorative Coins" (in English). The Central Bank of the Russian Federation. 2009-12-28. http://www.cbr.ru/eng/bank-notes_coins/memorable_coins/current_year_coins/print.asp?file=091228_eng.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

|

|||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||