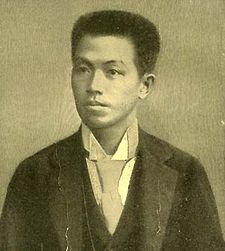

Emilio Aguinaldo

| Emilio Aguinaldo | |

|

|

|

|

|

| In office March 22, 1898 – April 1, 1901 |

|

| Prime Minister | Apolinario Mabini (Jan 21 - May 7, 1899) Pedro Paterno (May 7 - Nov 13, 1899) |

|---|---|

| Vice President | Mariano Trías (1897) |

| Succeeded by | Manuel Quezon |

|

|

|

| Born | March 22, 1869 Cavite El Viejo, Philippines (now Kawit) |

| Died | February 6, 1964 (aged 94) Quezon City, Philippines |

| Political party | Katipunan |

| Spouse(s) | Hilaria del Rosario (1896–1921) María Agoncillo(1882–1963) |

| Profession | Soldier Revolutionary |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature | |

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy[1][2] (March 22, 1869 – February 6, 1964) was a Filipino general, politician, and independence leader. He played an instrumental role during the Philippines' revolution against Spain, and the subsequent Philippine-American War that resisted American occupation.

Aguinaldo became the Philippines' first President. He was also the youngest (at age 29) to have become the country's president, and the longest-lived (having survived to age 94).

Contents |

Early Life

Family

The seventh of eight children of Carlos Aguinaldo y Jamir and Trinidad Famy y Valero (1820-1916), Emilio Aguinaldo was born on March 22, 1869 in Cavite El Viejo (now Kawit), Cavite province. His father was gobernadorcillo (town head), and, as members of the Chinese-Tagalog mestizo minority, they enjoyed relative wealth and power. As a young boy he received education from his great-aunt and later attended the town's elementary school. In 1880, he took up his secondary course education at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran, which he quit on his third year to return home instead to help his widowed mother manage their farm. At the age of 28, Miong, as he was popularly called, was elected cabeza de barangay of Binakayan, the most progressive barrio of Cavite El Viejo. He held this position serving for his town-mates for eight years. He also engaged in inter-island shipping, travelling as far south as the Sulu Archipelago. In 1893, the Maura Law was passed to reorganize town governments with the aim of making them more effective and autonomous, changing the designation of town head from gobernadorcillo to capitan municipal effective 1895. On January 1, 1895, Aguinaldo was elected town head, becoming the first person to hold the title of capitan municipal of Cavite El Viejo.

Personal Life

His first marriage was in 1896 with Hilaria Del Rosario (1877-1921). They had five children (Miguel, Carmen, Emilio Jr., María and Cristina). His second wife was María Agoncillo (1882-1963).

Descendants

Several of Aguinaldo's descendants became prominent political figures in their own right:

- Baldomero Aguinaldo, first cousin and leader of the Philippine Revolution.

- Cesar Virata, a grandnephew and served as Prime Minister of the Philippines from 1981 to 1986.

- Ameurfina Herrera, a granddaughter served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1979 to 1992.

- Miguel Aguinaldo, eldest son and Councilor of Imus, Cavite.

- Consuelo Aguinaldo, Gen. Aguinaldo's granddaughter and Emilio Aguinaldo, Jr.'s daughter.

- Emilio Aguinaldo, Jr., Gen. Aguinaldo's son.

- Emilio Aguinaldo III, Gen. Aguinaldo's grandson.

- Emilio "Orange" Aguinaldo IV, great-grandson and served as Vice Mayor of Kawit, Cavite.

- Emilio Aguinaldo V, Gen. Aguinaldo's great-great-grandson and grandson of Miguel Aguinaldo. Served as municipal councilor in Imus, Cavite.

- Lito Aguinaldo, father of Emilio Aguinaldo V and former councilor of Imus, Cavite.

- Reynaldo Aguinaldo, Mayor of Kawit, Cavite, Gen. Aguinaldo's grandson, son of Emilio Aguinaldo, Jr. and uncle of Emilio Aguinaldo IV.

- Federico “Hit” Poblete, Gen. Aguinaldo's grandson and served as Mayor of Imus, Cavite.

- Joseph Emilio Abaya, Gen. Aguinaldo's great grandson and Representative of 1st District of Cavite.

- Peter Aguinaldo Abaya, Gen. Aguinaldo's great grandson and president of Alternative Fuels Corp., an attached agency of the Philippine National Oil Corporation.

- Sandra Aguinaldo, Gen. Aguinaldo's great-granddaughter and TV reporter.

- Angelo Aguinaldo, Gen. Aguinaldo's great-grandson and curator.

His Great Grandchildren are elusive to the public eye and continue to support Aguinaldo's traditions.[3] Such as the awarding of the Philippine Military Academy Aguinaldo Saber Award. The youngest, Emiliana, currently continues to award.

Philippine Revolution

In 1895, Aguinaldo joined the Katipunan or the K.K.K., a secret organization led by Andrés Bonifacio, dedicated to the expulsion of the Spanish and independence of the Philippines through armed force. Aguinaldo used the nom de guerre Magdalo, in honor of Mary Magdalene. His local chapter of the Katipunan, headed by his cousin Baldomero Aguinaldo, was also called Magdalo.[4]

The Katipunan revolted against the Spanish colonizers in the last week of August 1896, starting in Manila. However, Aguinaldo and other Cavite rebels initially refused to join in the offensive due to lack of arms. Their absence contributed to Bonifacio's defeat in San Juan del Monte.[4] While Bonifacio and other rebels were forced to resort to guerrilla warfare, Aguinaldo and the Cavite rebels won major victories in set-piece battles, temporarily driving the Spanish out of their area.[4]

Conflict between the Magdalo and another Cavite Katipunan faction, the Magdiwang, led to Bonifacio's intervention in the province. The Cavite rebels then made overtures about establishing a revolutionary government in place of the Katipunan. Though Bonifacio already considered the Katipunan to be a government, he acquiesced and presided over elections held during the Tejeros Convention in Tejeros, Cavite on March 22, 1897. Away from his power base, Bonifacio lost the leadership to Aguinaldo, and was elected instead to the office of Secretary of the Interior. Even this was questioned by an Aguinaldo supporter, claiming Bonifacio had not the necessary schooling for the job. Insulted, Bonifacio declared the Convention null and void, and sought to return to his power base in Morong (present-day Rizal). He and his party were intercepted by Aguinaldo's men and violence resulted which left Bonifacio seriously wounded. Bonifacio was charged, tried and found guilty of treason by a Cavite military tribunal, and sentenced to death. After some vacillation, Aguinaldo confirmed the death sentence, and Bonifacio was executed on May 10, 1897 in the mountains of Maragondon in Cavite, even as Aguinaldo and his forces were retreating in the face of Spanish assault.[4]

Biak-na-Bato

Spanish pressure intensified, eventually forcing Aguinaldo's forces to retreat to the mountains. Emilio Aguinaldo signed the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. Under the pact, Aguinaldo agreed to end hostilities as well in exchange for amnesty and "$800,000 (Mexican)" (Aguinaldo's description of the amount)[5][6] as an indemnity. Aguinaldo took the money offered. On December 14, 1897, Aguinaldo and other Katipunan officials went into voluntary exile in Hong Kong. Emilio Aguinaldo was President and Mariano Trias (Vice President). Other officials included Antonio Montenegro for Foreign Affairs, Isabelo Artacho for the Interior, Baldomero Aguinaldo for the Treasury, and Emiliano Riego de Dios for War.

However, thousands of other Katipuneros continued to fight the Revolution against Spain for a sovereign nation. Unlike Aguinaldo who came from a privileged background, the bulk of these fighters were peasants and workers who were not willing to settle for 'indemnities.'

In early 1898, war broke out between Spain and the United States. Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines in May 1898. He immediately resumed revolutionary activities against the Spaniards, now receiving verbal encouragement from emissaries of the U. S.

Presidency

The insurgent First Philippine Republic was formally established with the proclamation of the Malolos Constitution on January 21, 1899 in Malolos, Bulacan and endured until the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo by the American forces on March 23, 1901 in Palanan, Isabela, which effectively dissolved the First Republic.

Aguinaldo appointed two premiers in his tenure. These were Apolinario Mabini and Pedro Paterno.

Administration and Cabinet

President Aguinaldo had two cabinets in the year 1899. Thereafter, the war situation resulted in his ruling by decree.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Domestic Programs

The Malolos Congress continued its sessions and accomplised certain positive tasks. The Spanish fiscal system was provisionally retained. The same was done with the existing taxes, save those upon cockfighting and other amusements. War taxes were levied and voluntary contributions were solicited. Customs duties were established. A national loan was launched. President Aguinaldo ordered schools open. Elementary education was made compulsory and free. The Filipino educator, Enrique Mendiola, founded the "Instituto de Burgos" and were appointed by the Director of Public Instruction. It offered courses in agriculture, surveying, and commerce, as well as a complete A.B course.

On October 1898 a government decree fixed the opening date of the "Universidad Literia".[7] Couses offered were Medicine, Surgery, Pharmacy, and Notary Public. The President of the Philippines appointed the professors thereof. They, in turn, chose the University rector. The first to occupy this position was Joaquin Gonzales. Later, he was succeeded by Dr. leo Ma. Guerrero.[8]

Philippine American War

On the night of February 4, 1899, a Filipino was shot by an American sentry. This incident is considered the beginning of the Philippine-American War, and open fighting soon broke out between American troops and pro-independence Filipinos. Superior American firepower drove Filipino troops away from the city, and the Malolos government had to move from one place to another.

Aguinaldo led resistance to the Americans, then retreated to northern Luzon with the Americans on his trail. On June 2, 1899, a telegram from Aguinaldo was received by Gen. Antonio Luna, a disciplinarian and brilliant general and looming rival in the military hierarchy, ordering him to proceed to Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija for a meeting at the Cabanatuan Church Convent. However, treachery was afoot, as Aguinaldo felt the need to rid himself of this new threat to power. Three days later (June 5), when Luna arrived, he learned Aguinaldo was not at the appointed place. As Gen. Luna was about to depart, he was shot, then stabbed to death by Aguinaldo's men. Luna was later buried in the churchyard, and Aguinaldo made no attempt to punish or even discipline Luna's murderers.

Less than two years later, after the famous Battle of Tirad Pass with the death of Gregorio del Pilar, one of his most trusted generals, Aguinaldo was captured in Palanan, Isabela on March 23, 1901 by US General Frederick Funston, with the help of Macabebe trackers (who saw Aguinaldo as a bigger problem than the Americans). The American task force gained access to Aguinaldo's camp by pretending to be captured prisoners.

Funston later noted Aguinaldo's "dignified bearing", "excellent qualities," and "humane instincts." Of course, Funston was writing this after Aguinaldo had volunteered to swear fealty to the United States, if only his life was spared. Aguinaldo pledged allegiance to America on April 1, 1901, formally ending the First Republic and recognizing the sovereignty of the United States over the Philippines. Nevertheless, many others (like Miguel Malvar and Macario Sakay) continued to resist the American occupation.

Post-Presidency

U.S. Territorial Period

During the United States occupation, Aguinaldo organized the Asociación de los Veteranos de la Revolución (Association of Veterans of the Revolution), which worked to secure pensions for its members and made arrangements for them to buy land on installment from the government.

When the American government finally allowed the Philippine flag to be displayed in 1919, Aguinaldo transformed his home in Kawit into a monument to the flag, the revolution and the declaration of Independence. His home still stands, and is known as the Aguinaldo Shrine.

Aguinaldo retired from public life for many years. In 1935, when the Commonwealth of the Philippines was established in preparation for Philippine independence, he ran for president but lost by a landslide to fiery Spanish mestizo Manuel L. Quezon. The two men formally reconciled in 1941, when President Quezon moved Flag Day to June 12, to commemorate the proclamation of Philippine independence.

Aguinaldo again retired to private life, until the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in World War II. He cooperated with the Japanese, making speeches, issuing articles and infamous radio addresses in support of the Japanese — including a radio appeal to Gen. Douglas MacArthur on Corregidor to surrender in order to spare the innocence of the Filipino youth.

After the Americans retook the Philippines, Aguinaldo was arrested along with several others accused of collaboration with the Japanese. He was held in Bilibid prison for months until released by presidential amnesty. In his trial, it was eventually deemed that his collaboration with the Japanese was made under great duress, and he was released.

Aguinaldo lived to see the recognition of independence to the Philippines July 4, 1946, when the United States Government fully recognized Philippine independence in accordance with the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934. He was 93 when President Diosdado Macapagal officially changed the date of independence from July 4 to June 12, 1898, the date Aguinaldo believed to be the true Independence Day. During the independence parade at the Luneta, the 93-year old former president carried the flag he raised in Kawit.

Post-American era

In 1950, President Elpidio Quirino appointed Aguinaldo as a member of the Council of State, where he served a full term. He returned to retirement soon after, dedicating his time and attention to veteran soldiers' interests and welfare.

He was given Doctor of Laws, Honoris Causa by the University of the Philippines in 1953.

In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal changed the celebration of Independence Day from July 4 to June 12.[n 1] Aguinaldo rose from his sickbed to attend the celebration of independence 64 years after he declared it.

Death

Aguinaldo died on February 6, 1964 of coronary thrombosis at the Veterans Memorial Hospital in Quezon City. He was 94 years old. His remains are buried at the Aguinaldo Shrine in Kawit, Cavite. When he died, he was the last surviving non-royal head of state (self-proclaimed) to have served in the 19th century.

In 1985, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas made a new 5-peso bill depicted with a portrait of Aguinaldo on the front of the bill. The back of the bill features the declaration of the Philippine independence on June 12, 1898 with Aguinaldo on the balcony of his house surrounded by crowds of rejoicing Filipinos holding the Philippine flag and proclaiming independence from Spain.

Notes

- ↑ On May 12, 1962, President Macapagal signed "Presidential Proclamation No. 28, Declaring June 12 as Philippine Independence Day".[9] There is no doubt that President Macapagal intended the proclamation to have that effect [10] and sources commonly assert this as fact,[11], but the operative paragraph of the proclamation declares a single day, "Tuesday, June 12, 1962, as a special public holiday throughout the Philippines ...". On August 4, 1964, Republic Act No. 4166 proclaimed the twelfth day of June as the Philippine Independence Day and renamed the fourth of July holiday to "Philippine Republic Day".[12]

See also

- Tagalog people

- Tejeros Convention

- Philippines

- Flag of the Philippines (designed by Aguinaldo)

- History of the Philippines

- Philippine Revolution

- Katipunan

- Hilaria Aguinaldo

- Spanish-American War

- Philippine-American War

- President of the Philippines

- Aguinaldo Shrine

- Cesar Virata

- List of Unofficial Presidents of the Philippines

References

- ↑ "Emilio Aguinaldo". The New Book of Knowledge, Grolier Incorporated. 1977.

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley. "Emilio Aguinaldo". In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines. Random House (1989). ISBN 0394594759.

- ↑ Ramos, Marlon (June 14, 2010). "Aguinaldo heirs creep into Cavite politics". Inquirer.net. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/regions/view/20070614-71175/Aguinaldo_heirs_creep_into_Cavite_politics. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Guererro, Milagros; Schumacher, S.J., John (1998), Reform and Revolution, Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 962-258-228-1

- ↑ Don Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy, Chapter II. The Treaty of Biak-na-bató, "True Version of the Philippine Revolution", Authorama Public Domain Books, http://www.authorama.com/true-version-of-the-philippine-revolution-3.html, retrieved 2007-11-16

- ↑ The Mexican dollar at the time was worth about 50 U.S. cents, according to Halstead... General Emilio Aguinaldo, a traitor of the Philippine Republic, during Spanish-American Regime.., Murat (1898), "XII. The American Army in Manila. General Emilio Aguinaldo, a traitor of the Philippine Republic, during Spanish-American Regime..", The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico, p. 126, http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=58428&pageno=122

- ↑ *Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (2005), The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898-1899., Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library (published 1972), p. 61, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=philamer;iel=1;view=toc;idno=aab1246.0001.001 (English translation by Sulpicio Guevara).

- ↑ Antonio Molino: The Philippines through the Centuries (Volume two), 1961

- ↑ Diosdado Macapagal, Proclamation No. 28 Declaring June 12 as Philippine Independence Day, Philippine History Group of Los Angeles, http://www.bibingka.com/phg/documents/jun12.htm, retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ Diosdado Macapagal (2002), "Chapter 4. June 12 as Independence Day", KALAYAAN, Philippine Information Agency, pp. 12–15, http://www.pia.gov.ph/pubs/kalayaan2001.pdf.

- ↑ Sharon Delmendo (2004), The star-entangled banner: one hundred years of America in the Philippines, University of the Philippines Press, p. 10, ISBN 9789715424844, http://books.google.com/?id=HhZKW4drY6MC.

- ↑ AN ACT CHANGING THE DATE OF PHILIPPINE INDEPENDENCE DAY FROM JULY FOUR TO JUNE TWELVE, AND DECLARING JULY FOUR AS PHILIPPINE REPUBLIC DAY, FURTHER AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE SECTION TWENTY-NINE OF THE REVISED ADMINISTRATIVE CODE, Chanrobles Law Library, August 4, 1964, http://www.chanrobles.com/republicacts/republicactno4166.html, retrieved 2009-11-11

Further reading

- Aguinaldo, Emilio (1964), Mga Gunita ng Himagsikan

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1984), Philippine History and Government, National Bookstore Printing Press

External links

- The Philippine Presidency Project

- CAUTUSAN: Gobierno Revolucionario nang Filipinas A decree dated January 2, 1899 signed by Emilio Aguinaldo establishing a council of government. An online document published by Filipiniana.net (archived from the original on 2007-12-11)

- Aguinaldo: A Narrative of Filipino Ambitions Book written by American Consul Wildman of Hong Kong regarding Emilio Aguinaldo and the Filipino-American War during the early 1900s. An online publication made by Filipiniana.net (archived from the original on 2008-02-12)

- General Emilio Aguinaldo’s “Confession”. Published in Filipiniana.net. (archived from the original on 2008-05-27)

- Works by Emilio Aguinaldo at Project Gutenberg

- Emilio Aguinaldo, Encyclopedia BritannicaOnline, http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9004099/Emilio-Aguinaldo, retrieved 2008-04-25

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New office | President of the Philippines 1899–1901 |

Vacant

Office nullified; Philippines had been ceded to the United States by Spain

Title next held by

Manuel L. Quezon |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||