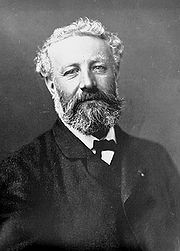

Jules Verne

| Jules Verne | |

|---|---|

Jules Verne |

|

| Born | Jules Gabriel Verne 8 February 1828 Nantes, France |

| Died | 24 March 1905 (age 77) Amiens, France |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | French |

| Genres | Science fiction, adventure novel |

| Notable work(s) | A Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, From the Earth to the Moon,The Mysterious Island |

|

Influences

Edgar Allan Poe, Alexandre Dumas, père, Victor Hugo, Daniel Defoe, Johann David Wyss, Józef Sękowski

|

|

|

Influenced

H.G. Wells, Julio Cortázar, Emilio Salgari, Louis Boussenard, William Golding, Paschal Grousset, Donald G. Payne, Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Luis Senarens

|

|

|

|

|

| Signature |  |

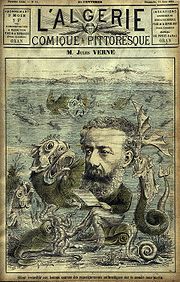

Jules Gabriel Verne (French pronunciation: [ʒyl vɛʁn]; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French author who helped pioneer the science-fiction genre. He is best known for his novels A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1869–1870), Around the World in Eighty Days (1873) and The Mysterious Island (1875).

Verne wrote about space, air, and underwater travel before navigable aircraft and practical submarines were invented, and before any means of space travel had been devised. Consequently he is often referred to as the "Father of science fiction", along with H. G. Wells,[1] Hugo Gernsback and Edgar Allan Poe.

Verne is the second most translated author of all time, only behind Agatha Christie, with 4223 translations, according to Index Translationum.[2] Some of his works have been made into films.

Contents |

Life and career

Early years

He was born in the bustling harbor city of Nantes in Western France. The oldest of five children, he spent his early years at home with his parents. The family spent summers in a country house just outside the city, on the banks of the Loire River. Verne and his brother Paul, of whom Verne was very fond, would often rent a boat for a franc a day.[3] The sight of the many ships navigating the river sparked Verne's imagination, as he describes in the autobiographical short story "Souvenirs d'Enfance et de Jeunesse". When Verne was nine, he and Paul were sent to boarding school at the Saint Donatien College (Petit séminaire de Saint-Donatien). As a child, he developed a great interest in travel and exploration, a passion he showed as a writer of adventure stories and science fiction. At twelve, he snuck onto a ship that was bound for India, the Coralie, only to be caught and severely whipped by his father. He famously stated, "I shall from now on only travel in my imagination."

At the boarding school, Verne studied Latin, which he used in his short story "Le Mariage de Monsieur Anselme des Tilleuls" in the mid 1850s. One of his teachers may have been the French inventor Brutus de Villeroi, professor of drawing and mathematics at Saint Donatien in 1842, and who later became famous for creating the U.S. Navy's first submarine, the Alligator. De Villeroi may have inspired Verne's conceptual design for the Nautilus in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, although no direct exchanges between the two men have been recorded. At Nantes in 1835, when De Villeroi and a companion submerged for two hours in a ten foot submarine, Verne was seven years old. For years afterward, De Villeroi carried on submarine experiments in Nantes.[4]

Literary debut

| French literature |

|---|

| By category |

| French literary history |

|

Medieval |

| French writers |

|

Chronological list |

| France portal |

| Literature portal |

After completing his studies at the lycée, Verne went to Paris to study law. About 1848, in conjunction with Michel Carré, he began writing librettos for operettas (he was co-librettist of Colin-Millard, a one act opera comique by Aristide Hignard). For some years his attentions were divided between the theatre and work, but some travelers' stories which he wrote for the Musée des Familles revealed to him his talent for writing fiction.

When Verne's father discovered that his son was writing rather than studying law, he promptly withdrew his financial support. Verne was forced to support himself as a stockbroker, which he hated despite being somewhat successful at it. During this period, he met Alexandre Dumas, père and Victor Hugo, who offered him writing advice. Dumas would become a close friend of Verne.[5]

Verne also met Honorine de Viane Morel, a widow with two daughters. They were married on 10 January 1857. With her encouragement, he continued to write and actively looked for a publisher. On 3 August 1861, their son, Michel Jean Verne, was born. A classic enfant terrible, Michel was sent to Mettray Penal Colony in 1876 and later married an actress (in spite of Verne's objections), had two children by his 16-year-old mistress, and buried himself in debts. The relationship between father and son did improve as Michel grew older.

Verne's situation improved when he met Pierre-Jules Hetzel, one of the most important French publishers of the 19th century, who also published Victor Hugo, George Sand, and Erckmann-Chatrian, among others. They formed an excellent writer-publisher team until Hetzel's death. Hetzel helped improve Verne's writings, which until then had been repeatedly rejected by other publishers. Hetzel read a draft of Verne's story about the balloon exploration of Africa, which had been rejected by other publishers for being "too scientific". With Hetzel's help, Verne rewrote the story, which was published in 1863 in book form as Cinq semaines en ballon (Five Weeks in a Balloon). Acting on Hetzel's advice, Verne added comical accents to his novels, changed sad endings into happy ones, and toned down various political messages.

In 1864, Verne wrote an admiring study of the works of Edgar Allan Poe (Edgar Poe et ses oeuvres, 1864) and it is not difficult to see Poe's works, published in France as Histoires extraordinaires (Extraordinary Stories), as a source of inspiration for Verne.[6] In fact, Verne was so intrigued by Poe's "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket" that he penned a sequel to the work entitled "An Antarctic Mystery." Verne set his story eleven years after the disappearance of Pym and recounts through the persona of Jeorling, a man of science, the adventures encountered during an expedition tracing Pym's travels.[7]

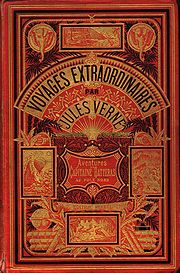

From that point to years after Verne's death, Hetzel published two or more volumes a year. The most successful of these include: Voyage au centre de la terre (Journey to the Centre of the Earth, 1864); De la terre à la lune (From the Earth to the Moon, 1865); Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, 1869); and Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (Around the World in Eighty Days), which first appeared in Le Temps in 1872. The series is collectively known as "Les Voyages Extraordinaires" ("extraordinary voyages"). Verne could now live on his writings. But most of his wealth came from the stage adaptations of Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (1874) and Michel Strogoff (1876), a relatively conventional adventure tale set in Tsarist Russia, which he adapted for the stage with Adolphe d'Ennery. In 1867 Verne bought a small ship, the Saint-Michel, which he successively replaced with the Saint-Michel II and the Saint-Michel III as his financial situation improved. On board the Saint-Michel III, he sailed around Europe. In 1870, he was appointed "Chevalier" (Knight) of the Légion d'honneur. After his first novel, most of his stories were first serialised in the Magazine d'Éducation et de Récréation, a Hetzel biweekly publication, before being published in the form of books. Jules' brother Paul contributed to a non-fiction story "Fortieth Ascent of Mont Blanc" ("Quarantième ascension du Mont-Blanc") to the collection of short stories, Doctor Ox (1874). According to the Unesco Index Translationum, Jules Verne regularly places among the top five most translated authors in the world.

Last years

On 9 March 1886, as Verne approached his own home, his twenty-five-year-old nephew Gaston, who suffered from paranoia, shot twice at him with a gun. One bullet missed, but the second entered Verne's left leg, giving him a permanent limp. Gaston spent the rest of his life in an asylum.

After the deaths of Hetzel and his beloved mother in 1887, Verne began writing darker works. This may have been due partly to changes in his personality, but an important factor was that Hetzel's son, who took over his father's business, was not as rigorous in his edits and corrections as Hetzel Sr. had been.

In 1888, Verne entered politics and was elected town councilor of Amiens, where he championed several improvements and served for fifteen years. Though elected from the left he stood with the right on the Dreyfus Affair and was anti-Dreyfusard,[8][9] although the theme of wrongful conviction and judicial corruption found in "The Kip Brothers", one of his last novels, suggests he may have become a Dreyfusard later in life.[10] In 1905, ill with diabetes, Verne died at his home, 44 Boulevard Longueville (now Boulevard Jules-Verne). His son Michel oversaw publication of his last novels Invasion of the Sea and The Lighthouse at the End of the World. The "Voyages extraordinaires" series continued for several years afterwards in the same rhythm of two volumes a year. It was later discovered that Michel Verne had made extensive changes in these stories, and the original versions were published at the end of the 20th century.

In 1863, Verne wrote Paris in the 20th Century, a novel about a young man who lives in a world of glass skyscrapers, high-speed trains, gas-powered automobiles, calculators, and a worldwide communications network, yet cannot find happiness and comes to a tragic end. Hetzel thought the novel's pessimism would damage Verne's then booming career, and suggested he wait 20 years to publish it. Verne put the manuscript in a safe, where it was discovered by his great-grandson in 1989. It was published in 1993.

Death

Jules Verne died on 24 March 1905 and was buried in the La Madeleine Cemetery in Amiens. In 2008, efforts were initiated to have him reburied in the Panthéon, alongside France's other literary giants.

Reputation in English-speaking countries

While Verne is considered in France as an author of quality books for young people, with a good command of his subjects, including technology and politics, his reputation in English-speaking countries suffered for a long time as a result of poor translation.

Some English publishers felt 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea portrayed the British Empire in a bad light, and the first English translator, Reverend Lewis Page Mercier, working under a pseudonym, removed many offending passages. Mrs. Agnes Kinloch Kingston (writing in the name of her husband, W.H.G. Kingston) deleted parts of The Mysterious Island such as those describing the political actions of Captain Nemo in his incarnation as an Indian nobleman freedom fighter. Such negative depictions were not, however, invariable in Verne's works; for example, Facing the Flag features, in the character of Lieutenant Devon, a heroic, self-sacrificing Royal Navy officer worthy of any created by British authors. In 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea itself, Captain Nemo, there of unidentified nationality, is balanced by Ned Land, a Canadian. Some of Verne's most famous heroes were British (e.g. Phileas Fogg in Around the World in Eighty Days).

Mercier and subsequent British translators also had trouble with the metric system that Verne used, sometimes dropping significant figures, at other times changing the unit to an Imperial measure without changing the corresponding value. Thus Verne's calculations, which in general were remarkably exact, were converted into mathematical gibberish. Also, artistic passages and sometimes whole chapters were cut to fit the work into a constrained space for publication.

For these reasons, Verne's work initially acquired a reputation in English-speaking countries of not being fit for adult readers. This in turn prevented it from being taken seriously enough to merit new translations, and those of Mercier and others were reprinted decade after decade. Only from 1965 on have some of his novels received more accurate translations, but even today Verne's work has not been fully rehabilitated in the English-speaking world.

Verne's works may also reflect the bitterness France felt in the wake of its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and the consequent loss of Alsace and Lorraine. The Begum's Millions (Les Cinq cents millions de la Begum) of 1879 gives a highly stereotypical depiction of Germans as monstrously cruel militarists. By contrast, the rare portrayals of Germans are positive in pre-1871 works such as Journey to the Centre of the Earth, in which almost all the protagonists, including the sympathetic first-person narrator, are German.

Hetzel's influence

Hetzel substantially influenced the writings of Verne, who was so happy to finally find a willing publisher that he agreed to almost all changes that Hetzel suggested. Hetzel rejected at least one novel (Paris in the 20th Century), and asked Verne to make significant changes in his other drafts. One of the most important changes Hetzel imposed on Verne was the adoption of a more optimistic tone. Verne was in fact not an enthusiast of technological and human progress, as can be seen in the works he created both before he met Hetzel and after the publisher's death. For example, The Mysterious Island originally ended with the survivors returning to mainland forever nostalgic about the island. Hetzel decided that the heroes should live happily, so in the revised draft, they use their fortunes to build a replica of the island. Many translations are like this. Also, in order not to offend France's then-ally, Russia, the famous Captain Nemo was changed from a Polish refugee avenging the partitions of Poland and the death of his family, killed in the reprisals following the January Uprising, to an Indian prince fighting the British Empire after the Sikh War.

Predictions

Jules Verne's novels have been noted for being startlingly accurate anticipations of modern times. Paris in the 20th Century is an often cited example of this as it arguably describes air conditioning, automobiles, electricity, television, even the Internet, and other modern conveniences very similar to their real world counterparts.

Another example is From the Earth to the Moon, which, apart from using a space gun instead of a rocket, is uncannily similar to the real Apollo Program, as three astronauts are launched from the Florida peninsula and recovered through a splash landing. In the book, the spacecraft is launched from "Tampa Town"; Tampa, Florida is approximately 130 miles from NASA's actual launching site at Cape Canaveral.[11]

In other works, Verne predicted the inventions of helicopters, jukeboxes, and other later devices.

He also predicted the existence of underwater hydrothermal vents that were not discovered until years after he wrote about them.

Scholars' jokes

Verne, who had a large archive and always kept up with scientific and technological progress, sometimes seemed to joke with the readers, using so-called "scholars' jokes" (that is, a joke that only a scientist may recognise). For instance, in Dick Sand, A Captain at Fifteen, a Manticora beetle helps Cousin Bénédict to escape from imprisonment when Bénédict, unguarded, follows the beetle out of the garden. Since the beetle escapes from Cousin Bénédict by flying away, when in fact the genus is flightless, it is possible that this is one such joke. Another example appears in Mysterious Island, where the main character's dog is attacked by a wild dugong, even though the dugong, like its North American cousin, the manatee, is a herbivorous mammal. Also in Mysterious Island, because of its fauna and flora, the sailor Bonadventure Pencroff asks Cyrus Harding whether the latter believes that islands (like the one they are on) are made especially to be ideal ones for castaways. In From the Earth to the Moon, it was the material used in the creation of the cannon, although in this case it was probably poetic license in order to make the description of the making of the gun far more dramatic, or The Begum's Millions, where the methods used for making steel in "Steel City", described as the most modern steel factory in the world, were rather dated, but, again, much more spectacular to describe. (See Neff, 1978)

Bibliography

Verne wrote numerous works, most famous of which are the 54 novels part of the Voyages Extraordinaires. He also wrote short stories, essays, plays, and poems.

Note: only the dates of the first English translation and the most common translation title are given.

Novels

| # | French publication | English translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Year | Title | Year | |

| 1. | Cinq Semaines en ballon | 1863 | Five Weeks in a Balloon | 1869 |

| 3. | Voyage au centre de la Terre | 1864 | A Journey to the Center of the Earth | 1871 |

| 4. | De la terre à la lune | 1865 | From the Earth to the Moon | 1865 |

| 2. | Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras | 1866 | The Adventures of Captain Hatteras | 1874–75 |

| 5. | Les Enfants du capitaine Grant | 1867–68 | In Search of the Castaways | 1873 |

| 6. | Vingt mille lieues sous les mers | 1869–70 | Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea | 1872 |

| 7. | Autour de la lune | 1870 | Around the Moon | 1873 |

| 8. | Une ville flottante | 1871 | A Floating City | 1874 |

| 9. | Aventures de trois Russes et de trois Anglais | 1872 | The Adventures of Three Englishmen and Three Russians in South Africa | 1872 |

| 10. | Le Pays des fourrures | 1873 | The Fur Country | 1873 |

| 11. | Le Tour du Monde en quatre-vingts jours | 1873 | Around the World in Eighty Days | 1875 |

| 12. | L'Île mysterieuse | 1874–75 | The Mysterious Island | 1874 |

| 13. | Le Chancellor | 1875 | The Survivors of the Chancellor | 1875 |

| 14. | Michel Strogoff | 1876 | Michael Strogoff | 1876 |

| 15. | Hector Servadac | 1877 | Off on a Comet | 1877 |

| 16. | Les Indes noires | 1877 | The Child of the Cavern | 1877 |

| 17. | Un capitaine de quinze ans | 1878 | Dick Sand, A Captain at Fifteen | 1878 |

| 18. | Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Bégum | 1879 | The Begum's Millions | 1879 |

| 19. | Les Tribulations d'un chinois en Chine | 1879 | Tribulations of a Chinaman in China | 1879 |

| 20. | La Maison à vapeur | 1880 | The Steam House | 1880 |

| 21. | La Jangada | 1881 | Eight Hundred Leagues on the Amazon | 1881 |

| 22. | L'École des Robinsons | 1882 | Godfrey Morgan | 1883 |

| 23. | Le Rayon vert | 1882 | The Green Ray | 1883 |

| 24. | Kéraban-le-têtu | 1883 | Kéraban the Inflexible | 1883–84 |

| 25. | L'Étoile du sud | 1884 | The Vanished Diamond | 1885 |

| 26. | L'Archipel en feu | 1884 | The Archipelago on Fire | 1885 |

| 27. | Mathias Sandorf | 1885 | Mathias Sandorf | 1885 |

| 28. | Un billet de loterie | 1886 | The Lottery Ticket | 1886 |

| 29. | Robur-le-Conquérant | 1886 | Robur the Conqueror | 1887 |

| 30. | Nord contre Sud | 1887 | North Against South | 1887 |

| 31. | Le Chemin de France | 1887 | The Flight to France | 1888 |

| 32. | Deux Ans de vacances | 1888 | Two Years' Vacation | 1889 |

| 33. | Famille-sans-nom | 1889 | Family Without a Name | 1889 |

| 34. | Sans dessus dessous | 1889 | The Purchase of the North Pole | 1890 |

| 35. | César Cascabel | 1890 | César Cascabel | 1890 |

| 36. | Mistress Branican | 1891 | Mistress Branican | 1891 |

| 37. | Le Château des Carpathes | 1892 | Carpathian Castle | 1893 |

| 38. | Claudius Bombarnac | 1892 | Claudius Bombarnac | 1894 |

| 39. | P’tit-Bonhomme | 1893 | Foundling Mick | 1895 |

| 40. | Mirifiques Aventures de Maître Antifer | 1894 | Captain Antifer | 1895 |

| 41. | L'Île à hélice | 1895 | Propeller Island | 1896 |

| 42. | Face au drapeau | 1896 | Facing the Flag | 1897 |

| 43. | Clovis Dardentor | 1896 | Clovis Dardentor | 1897 |

| 44. | Le Sphinx des glaces | 1897 | An Antarctic Mystery | 1898 |

| 45. | Le Superbe Orénoque | 1898 | The Mighty Orinoco | 2002 |

| 46. | Le Testament d'un excentrique | 1899 | The Will of an Eccentric | 1900 |

| 47. | Seconde Patrie | 1900 | The Castaways of the Flag | 1923 |

| 48. | Le Village aérien | 1901 | The Village in the Treetops | 1964 |

| 49. | Les Histoires de Jean-Marie Cabidoulin | 1901 | The Sea Serpent | 1967 |

| 50. | Les Frères Kip | 1902 | The Kip Brothers | 2007 |

| 51. | Bourses de voyage | 1903 | Traveling Scholarships | n/a |

| 52. | Un drame en Livonie | 1904 | A Drama in Livonia | 1967 |

| 53. | Maître du monde | 1904 | Master of the World | 1911 |

| 54. | L'Invasion de la mer | 1905 | Invasion of the Sea | 2001 |

Play

- (1882) Voyage à travers l'impossible; English translation: Voyage through the Impossible (2003)

Apocryphal and posthumous novels

- (1885) L'Épave du Cynthia; English translation: The Waif of the Cynthia (1885), with André Laurie (pseudonym of Paschal Grousset), but actually the work of Grousset alone[12]

- (1905) Le Phare du bout du monde; English translation: The Lighthouse at the End of the World (1923), modified by Michel Verne

- (1906) Le Volcan d'or; English translation: The Golden Volcano: The Claim on Forty Mile Creek and Flood and Flame (2 vols., 1962), modified by Michel Verne

- (1907) L'Agence Thompson and Cº; English translation: The Thompson Travel Agency: Package Holiday and End of the Journey (2 vols., 1965), written by Michel Verne

- (1908) La Chasse au météore; English translation: The Chase of the Golden Meteor (1909), modified by Michel Verne

- (1908) Le Pilote du Danube; English translation: The Danube Pilot (1967), modified by Michel Verne

- (1909) Les Naufragés du Jonathan; English translation: The Survivors of the 'Jonathan': The Masterless Man and The Unwilling Dictator (2 vols., 1962), modified by Michel Verne

- (1910) Le Secret de Wilhelm Storitz; English translation: The Secret of William Storitz (1963), modified by Michel Verne

- (1919) L'Étonnante Aventure de la mission Barsac; English translation: The Barsac Mission: Into the Niger Bend and The City of the Sahara (2 vols., 1960), written by Michel Verne

- (1989) Voyage en Angleterre et en Ecosse; English translation: Backwards to Britain (1992), written in 1859

- (1994) Paris au XXe siècle; English translation: Paris in the Twentieth Century (1996), written in 1863

Short story collections

- (1874) Le Docteur Ox; English translation: Doctor Ox (1874)

- (1910) Hier et Demain; English translation: Yesterday and Tomorrow (1965)

Short stories

- (1851) "Un drame au Mexique"; English translation: "A Drama in Mexico" (1876)

- (1851) "Un drame dans les airs"; English translation: "A Drama in the Air" (1852)

- (1852) "Martin Paz"; English translation: "Martin Paz" (1875)

- (1854) "Maître Zacharius"; English translation: "Master Zacharius" (1874)

- (1855) "Un hivernage dans les glaces"; English translation: "A Winter Amid the Ice" (1874)

- (1864) "Le Comte de Chanteleine"; English translation: "The Count of Chanteleine" (n/a)

- (1865) "Les Forceurs de blocus"; English translation: "The Blockade Runners" (1874)

- (1872) "Une fantaisie du docteur Ox"; English translation: "Dr. Ox's Experiment" (1874)

- (1875) "Une ville idéale"; English translation: "An Ideal City" (1965)

- (1879) "Les Révoltés de la Bounty"; English translation: "The Mutineers of the Bounty" (1879)

- (1881) "Dix Heures en chasse"; English translation: "Ten Hours Hunting" (1965)

- (1884) "Frritt-Flacc"; English translation: "Frritt-Flacc" (1892)

- (1887) "Gil Braltar"; English translation: "Gil Braltar" (1958)

- (1891) "La Journée d'un journaliste américain en 2889"; English translation: "In the Year 2889" (1889)

- (1891) "Aventures de la famille Raton"; English translation: "Adventures of the Rat Family" (1993)

- (1893) "Monsieur Ré-Dièze et Mademoiselle Mi-Bémol"; English translation: "Mr. Ray Sharp and Miss Me Flat" (1965)

Apocryphal short stories

- (1888) "Un Express de l'avenir"; English translation: "An Express of the Future" (1895), written by Michel Verne

- (1910) "La Destinée de Jean Morénas"; English translation: "The Fate of Jean Morenas" (1965), written by Michel Verne

- (1910) "L'Éternel Adam"; English translation: "The Eternal Adam" (1957), written by Michel Verne

Non-fiction works

- (1857) Salon de 1857 (art criticism); no English translation

- (1864) "Edgar Poe et ses oeuvres" (Edgar Allan Poe and his works)

- (1866) Géographie illustrée de la France et de ses colonies; English translation: Illlustrated Geography of France and its Colonies (n/a), with Théophile Lavallée

- Histoire des grands voyages et des grands voyageurs; English translation: Celebrated Travels and Travellers

- (1878) Découverte de la terre; English translation: The Exploration of the World (1879)

- (1879) Les Grand navigateurs du XVIIIème siècle; English translation: The Great Navigators of the Eighteenth Century (1879)

- (1880) Les Voyageurs du XIXème siècle; English translation: The Great Explorers of the Nineteenth Century (1881)

Imitations by other writers

The Wizard of the Sea by Roy Rockwood is a clear copy of Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, apart from the first chapter(s). One or two other of Rockwood's titles also seem to (lesser) resemble some of Verne's, e.g. compare Five Thousand Miles Underground to Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

See also

About Verne:

- Jules Verne Museum in Nantes, France

Museum entrance |

Jules Verne Museum building |

Other science-fiction pioneers:

- Paschal Grousset, another French science-fiction author

- Emilio Salgari, Opéra-bouffean Italian science-fiction and adventure writer

- Osip Senkovsky, Polish-Russian journalist and entertainer

- Oshikawa Shunro, a Japanese science-fiction pioneer

Inspired by Verne:

- The Secret Adventures of Jules Verne TV series

- Jules Verne ATV, an ATV named after Verne

- Steampunk, a style that took inspiration from Verne.

- Vernian Process, a music project inspired in name and theme.

Films based on works of Jules Verne

Jules Verne's works have inspired filmmakers almost from the birth of cinema. Georges Méliès, one of the earliest pioneers of French cinema, who had a taste for the fantastic, adapted some of Verne's works prior to 1910. Most of Verne's most famous novels, and some of his lesser known ones, received French, American, German, and Soviet adaptations in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, but probably the best known film adaptations of Verne's works came from American studios in the mid-1950s to early 1960s. These included Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), a production of Around the World in 80 Days that won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1956, a production of From the Earth to the Moon in 1958, Journey to the Center of the Earth in 1959, Mysterious Island in 1961, and In Search of the Castaways in 1962. These were large-scale productions featuring top American, British, and international stars.

While American studios' interest in Verne waned after this period, productions in other countries and smaller scale American productions have continued pretty much without interruption since the invention of film, up to this day. A recent example is the 2008 remake of Journey to the Center of the Earth (which was in 3D, starred Brendan Fraser, and was a highly successful box office hit). Other notable twenty-first century adaptations include the 2004 remake of Around the World in 80 Days (starring Steve Coogan and Jackie Chan) and the 2005 version of Mysterious Island (starring Patrick Stewart) which was only loosely based on the novel. There were also references to many of Verne's works in the unsuccessful 2003 film The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. In 2008, three British film-makers announced their upcoming film adaptation of "Clovis Dardentor", one of Verne's lesser known works.

The majority of the many film and television productions of Verne's works have concentrated on his most famous novels, but there have also been film adaptations of many of his lesser known works, such as The Lighthouse at the End of the World, The Carpathian Castle, and The Vanished Diamond, filmed as The Southern Star. Michael Strogoff has been a particularly popular property for adaptation by non-Americans, having been filmed at least a dozen times for cinema and television, starting in 1910.

Many famous actors have appeared in Verne films, including James Mason, Kirk Douglas, Maurice Chevalier, Peter Lorre, David Niven, Shirley MacLaine, Joseph Cotton, Lionel Barrymore, Orson Welles, Vincent Price, Yul Brynner, Jackie Chan, Brendan Fraser, and even the Three Stooges. The 1956 American version of Around the World in 80 Days is sometimes credited with inventing the concept of cameo appearances by big stars, and had (often very brief) appearances by a dizzying array of famous performers, including Frank Sinatra, John Gielgud, Noel Coward, Charles Boyer, Fernandel, Trevor Howard, Cesar Romero, George Raft, Buster Keaton, Marlene Dietrich, Ronald Colman, and many others.

Verne has also inspired Pop Culture, as evinced by the music video, Tonight, Tonight, by, Smashing Pumpkins, heavily influenced by a Georges Melies adaptation of, From the Earth to the Moon. Also, in, Back to the Future, Part III, "Doc" Brown & Clara Clayton bond over their mutual admiration of Verne's literature.

There have also been animated adaptations. The story Two Years Vacation was turned into a made-for-TV animation Japanese studio Nippon Animation under the title of The Story of Fifteen Boys (Japanese: 十五少年漂流記). An even more successful adaptation was the Spanish animated adaptation of Around the World in 80 Days, Around the World with Willy Fog. There is also a very loose anime adaption of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea under the name Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water, produced by Studio Gainax and written and directed by Hideaki Anno, best known for the Neon Genesis Evangelion franchise.

References

- ↑ Adam Roberts (2000), Science Fiction, London: Routledge, p. 48, ISBN 0-415-19204-8

- ↑ Unesco. "Most Translated Authors of All Time". Index Translationum. http://databases.unesco.org/xtrans/stat/xTransStat.a?VL1=A&top=50&lg=0. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ↑ Jules Verne (1995), Monna Lisa; suivi de Souvenirs d'enfance et de jeunesse, Paris: L'Herne, p. 101. ISBN 2-85197-328-2.

- ↑ Lincoln and the Tools of War by Robert V. Bruce — University of Illinois Press ISBN 978-0252060908 p 176

- ↑ Peggy Teeters (1993), Jules Verne: The Man Who Invented Tomorrow, New York: Walker, p. 24. ISBN 0802781896.

- ↑ "William Butcher, ''Journey to the Centre of the Earth'', Oxford U Press, 1992". Ibiblio.org. http://www.ibiblio.org/julesverne/books/journey_to_the_centre_of_the_earth.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ↑ "An Antarctic Mystery", The Gregg Press, 1975

- ↑ Walter A. McDougall (2001), "Journey to the Center of Jules Verne... and Us", Watch on the West 2, n. 4.

- ↑ William Butcher (2007), "A Chronology of Jules Verne", in Jules Verne, Lighthouse at the End of the World, Lincoln (NE): University of Nebraska Press, p. XXXVII, ISBN 0803246765.

- ↑ Jim Luce (2009), "[1]", "Jules Verne's Kip Brothers Translated into English after 100 Years," The Huffington Post

- ↑ Norman Wolcott (2005), A Jules Verne Centennial: 1905–2005, Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

- ↑ Volker Dehs, Jean-Michel Margot and Zvi Har’El, "The Complete Jules Verne Bibliography, X: Apocrypha". Retrieved on 2008-11-10.

Further reading

- William Butcher, Arthur C. Clarke (Introduction) (2006). Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography. ISBN 1-56025-854-3

- Peter Costello, Jules Verne: Inventor of Science Fiction. ISBN 0-684-15824-8

- Herbert R. Lottman (1997). Jules Verne: An Exploratory Biography. ISBN 0-312-14636-1

- Françoise I. Schiltz (2007). The Future Re-visited: 1950s American Film Adaptations of Jules Verne Novels. PhD in Film Studies. University of Southampton. School of Humanities.

- Marc Jakubowski Jules Verne, l'Oeuvre d'une Vie. 2001–2004

- Jean Jules-Verne (1976). Jules Verne, A Biography. ISBN 0-8008-4439-4

- Philippe Melot et Jean-Marie Embs (2005).Le Guide Jules Verne.Les Editions de l'Amateur,Paris. ISBN 2-85917-417-6

- Ondřej Neff, Podivuhodný svět Julese Vernea (The Extraordinary World of Jules Verne), Prague, (1978)

- Edward J. Gallagher, Judith A. Mistichelli, and John A. Van Eerde. (1980). Jules Verne: A primary and secondary bibliography. Boston: MA, G. K. Hall & Co.

- Arthur B. Evans (1988). Jules Verne Rediscovered: Didacticism and the Scientific Novel. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Andrew Martin (1990). The Mask of the Prophet: The Extraordinary Fictions of Jules Verne. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lawrence Lynch (1992). Jules Verne. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Edmund Smyth, ed. (2000). Jules Verne: Narratives of Modernity. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Timothy Unwin (2005). Jules Verne: Journeys in Writing. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

External links

- Works by Jules Verne at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- Works by or about Jules Verne at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- Jules Verne at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Les Voyages Extraordinaires — list of Verne works Compiled by Dennis Kytasaari

- Jules Verne's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography

- A Chronology of Jules Verne

- Biography of Jules Verne

- Jules Verne: A Reappraisal, by William Butcher

- Jules Verne: An Exploratory Biography, by Herbert R. Lottman — a review

- A Jules Verne Centennial: 1905–2005

- Academic scholarship on Jules Verne

- A Jules Verne Centenary - special 2005 issue of Science Fiction Studies

- "Jules Verne in English: A Bibliography of Modern Editions and Scholarly Studies"

- List of audio books at LibriVox by Verne

- Zvi Har'El's Jules Verne Collection, including the Jules Verne Virtual Library, online sources of 51 of Jules Verne's novels translated into eight languages

- The Jules Verne Collecting Resource Page, complete online sources, posters, cards, autographs, first edition covers, etc.

- "Jules Verne: Father of Science Fiction?", John Derbyshire, The New Atlantis, Number 12, Spring 2006, pp. 81–90. A review of four new Jules Verne translations from the "Early Classics of Science Fiction" series by Wesleyan University Press.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||