Kurgan hypothesis

|

Indo-European topics |

|---|

| Indo-European languages (list) |

| Albanian · Armenian · Baltic Celtic · Germanic · Greek Indo-Iranian (Indo-Aryan, Iranian) Italic · Slavic extinct: Anatolian · Paleo-Balkan (Dacian, |

| Proto-Indo-European language |

| Vocabulary · Phonology · Sound laws · Ablaut · Root · Noun · Verb |

| Indo-European language-speaking peoples |

| Europe: Balts · Slavs · Albanians · Italics · Celts · Germanic peoples · Greeks · Paleo-Balkans (Illyrians · Thracians · Dacians) ·

Asia: Anatolians (Hittites, Luwians) · Armenians · Indo-Iranians (Iranians · Indo-Aryans) · Tocharians |

| Proto-Indo-Europeans |

| Homeland · Society · Religion |

| Indo-European studies |

The Kurgan hypothesis (also theory or model) is one of the proposals about early Indo-European origins, which postulates that the people of an archaeological "Kurgan culture" (a term grouping the Yamna, or Pit Grave, culture and its predecessors) in the Pontic steppe were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language. The term is derived from kurgan (курган) Turkic[1] word for a tumulus or burial mound.

The Kurgan model is the most widely accepted scenario of Indo-European origins,[2][3] An alternative model is the Anatolian urheimat. Many Indo-Europeanists are agnostic on the question.

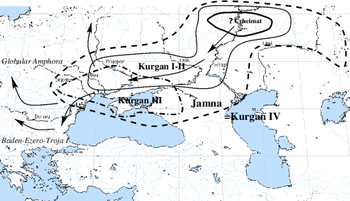

The Kurgan hypothesis was first formulated in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who defined the "Kurgan culture" as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper/Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennum BC). The bearers of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BC expanded throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.[4]

Contents |

Overview

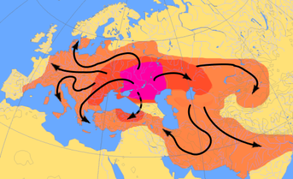

When it was first proposed in 1956, in "The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Part 1", Marija Gimbutas's contribution to the search for Indo-European origins was a pioneering interdisciplinary synthesis of archaeology and linguistics. The Kurgan model of Indo-European origins identifies the Pontic-Caspian steppe as the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) Urheimat, and a variety of late PIE dialects are assumed to have been spoken across the region. According to this model, the Kurgan culture gradually expanded until it encompassed the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe, Kurgan IV being identified with the Pit Grave culture of around 3000 BC.

The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire Pit Grave region, and is attributed to the domestication of the horse and later the use of early chariots.[5] The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Sredny Stog culture north of the Azov Sea in Ukraine, and would correspond to an early PIE or pre-PIE nucleus of the 5th millennium BC.[5] The earliest known chariot was discovered at Krivoye Lake and dates to c. 2000 BC.[6]

Subsequent expansion beyond the steppes led to hybrid, or in Gimbutas's terms "kurganized" cultures, such as the Globular Amphora culture to the west. From these kurganized cultures came the immigration of proto-Greeks to the Balkans and the nomadic Indo-Iranian cultures to the east around 2500 BC.

Mallory’s inconclusiveness about the westward Indo-European migrations was cited by linguist Kortlandt[7], to conclude that archaeological evidence is pointless beyond what can be motivated from a linguistic point of view. From the 1990s on, new archaeological evidence from Northern European prehistoric cultures resulted in new questions concerning the influence and expansion of Kurgan cultures to the west. The pan-European migrations and process of "kurganization", especially of Corded Ware cultures, may not have been as extensive as Gimbutas believed.[8]

Kurgan culture

The model of a "Kurgan culture" postulates cultural similarity between the various cultures of the Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age (5th to 3rd millennia BC) Pontic-Caspian steppe to justify the identification as a single archaeological culture or cultural horizon. The eponymous construction of kurgans is only one among several factors. As always in the grouping of archaeological cultures, the dividing line between one culture and the next cannot be drawn with any accuracy and will be open to debate.

Cultures forming part of the "Kurgan horizon":

- Bug-Dniester (6th millennium)

- Samara (5th millennium)

- Kvalynsk (5th millennium)

- Sredny Stog (mid-5th to mid-4th millennia)

- Dnieper-Donets (5th to 4th millennia)

- Usatovo culture (late 4th millennium)

- Maikop-Dereivka (mid-4th to mid-3rd millennia)

- Yamna (Pit Grave): this is itself a varied cultural horizon. Spanning the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe from the mid-4th to the 3rd millennium BC

Gimbutas defined and introduced the term "Kurgan culture" in 1956 with the intention to introduce a "broader term" that would combine Sredny Stog II, Pit-Grave and Corded ware horizons (spanning the 4th to 3rd millennia in much of Eastern and Northern Europe).[9] By the 1980s, it had become clear that this extended "Corded Ware-Battle Axe-Tumulus" burial complex envisaged by Gimbutas needed to be considered separately, under the heading of (3rd millennium) "Kurganization" (spread of "Kurgan elements" beyond the area of the Kurgan culture proper). Mallory (1986, p. 308) points out that "by the mid-5th millennium BC, we already have very striking cultural similarities from the Dnieper-Donets culture in the west to the Samara culture of the middle Volga ... this is continued in the later Sredny Stog period." The "Yamna culture in all its regional variants" arose later, and may already represent diversification.

The comparison of cultural similarities of these cultures is a question of archaeology independent of hypotheses regarding the Proto-Indo-European language. The postulate of these 5th millennium "cultural similarities" informed by archaeology are a prerequisite of the "Kurgan model" which identifies the chalcolithic (5th millennium) Pontic-Caspian steppe as the locus of Proto-Indo-European.

Stages of culture and expansion

Gimbutas' original suggestion identifies four successive stages of the Kurgan culture:-

- Kurgan I, Dnieper/Volga region, earlier half of the 4th millennium BC. Apparently evolving from cultures of the Volga basin, subgroups include the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures.

- Kurgan II–III, latter half of the 4th millennium BC. Includes the Sredny Stog culture and the Maykop culture of the northern Caucasus. Stone circles, early two-wheeled chariots, anthropomorphic stone stelae of deities.

- Kurgan IV or Pit Grave culture, first half of the 3rd millennium BC, encompassing the entire steppe region from the Ural to Romania.

There were proposed to be three successive "waves" of expansion:-

- Wave 1, predating Kurgan I, expansion from the lower Volga to the Dnieper, leading to coexistence of Kurgan I and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. Repercussions of the migrations extend as far as the Balkans and along the Danube to the Vinca and Lengyel cultures in Hungary.

- Wave 2, mid 4th millennium BC, originating in the Maykop culture and resulting in advances of "kurganized" hybrid cultures into northern Europe around 3000 BC (Globular Amphora culture, Baden culture, and ultimately Corded Ware culture). According to Gimbutas this corresponds to the first intrusion of Indo-European languages into western and northern Europe.

- Wave 3, 3000–2800 BC, expansion of the Pit Grave culture beyond the steppes, with the appearance of the characteristic pit graves as far as the areas of modern Romania, Bulgaria and eastern Hungary, coincident with the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture (c.2750 BC).

Secondary Urheimat

The "kurganized" Globular Amphora culture in Europe is proposed as a "secondary Urheimat" of PIE, the culture separating into the Bell-Beaker culture and Corded Ware culture around 2300 BC. This ultimately resulted in the European IE families of Italic, Celtic and Germanic languages, and other, partly extinct, language groups of the Balkans and central Europe, possibly including the proto-Mycenaean invasion of Greece.

Timeline

- 4500–4000: Early PIE. Sredny Stog, Dnieper-Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse (Wave 1).

- 4000–3500: The Pit Grave culture (a.k.a. yamna culture), the prototypical kurgan builders, emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus. Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time.

- 3500–3000: Middle PIE. The Pit Grave culture is at its peak, representing the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, early two-wheeled proto-chariots, predominantly practicing animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. Contact of the Pit Grave culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora Baden cultures (Wave 2). The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to Pit Grave territory. Probable early Satemization.

- 3000–2500: Late PIE. The Pit Grave culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe (Wave 3). The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga, corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, still in loose contact enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups, except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, which are already isolated from these processes. The Centum-Satem break is probably complete, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active.

Genetics

.jpg)

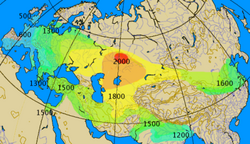

During the last glacial maximum (25,000 to 13,000 years ago), it is likely that the population of Europe retreated into refuges, one being Ukraine. A specific haplogroup R1a1 defined by the M17 (SNP marker) of the Y chromosome (see:[3] for nomenclature) is associated by some researchers with the Kurgan culture. The haplogroup R1a1 is "currently found in central and western Asia, Pakistan, India, and in Slavic populations of Eastern Europe", but it is rare in most countries of Western Europe (e.g. France, or some parts of Great Britain) (see [4] [5]). However, 23.6% of Norwegians, 18.4% of Swedes, 16.5% of Danes, 11% of Saami share this lineage ([6]). Investigations suggest the Hg R1a1 gene expanded from the Dniepr-Don Valley, between 13,000 and 7600 years ago, and was linked to the reindeer hunters of the Ahrensburg culture that started from the Dniepr valley in Ukraine and reached Scandinavia 12,000 years ago.[10] Alternatively, it has been suggested that R1a1 arrived in southern Scandinavia during the time of the Corded Ware culture.[11]

Ornella Semino et al. (see [7]) propose a postglacial spread of the R1a1 gene during the Late Glacial Maximum subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward. R1a1 is most prevalent in Poland, Russia, and Ukraine and is also observed in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Central Asia and India.

Recent genetic studies seem to confirm a west Eurasian origin for most of the Y-DNA haplogroup R1a1 likely linked to early Indo-European populations. Remains of the Andronovo culture horizon (strongly supposed to be culturally indo-Iranian) of south Siberia were found to be 90% of west Eurasian origin during the Bronze Age and associated almost exclusively with haplogroup R1a1 (and 77% overall, in the Bronze/Iron Age timeframe). The DNA testing also indicated a high prevalence of people with characteristics such as blue (or green) eyes, fair skin and light hair, implying even more an origin close to Europe for this population (see [8]). Remains in Kazakhstan of the Bronze/Iron Age timeframe, also of the Andronovo culture horizon, were also mostly of west Eurasian stock (see [9]).

Several 4600 year-old human remains at a Corded Ware site in Eulau, Germany, were also found to belong to haplogroup R1a1 (see [10]).

These elements tend to strongly support the Kurgan hypothesis.

Another marker that closely corresponds to Kurgan migrations is distribution of blood group B allele, mapped by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza. The distribution of blood group B allele in Europe matches the proposed map of Kurgan Culture, and Haplogroup R1a1 (YDNA) distribution.

Kortlandt's revision

Frederik Kortlandt (comparative linguistics, University of Leiden) in 1989 proposed a revision of the Kurgan model.[7] He states the main objection which can be raised against Gimbutas' scheme (e.g., 1985: 198) is that it starts from the archaeological evidence and looks for a linguistic interpretation. Starting from the linguistic evidence and trying to fit the pieces into a coherent whole, he arrives at the following picture: The territory of the Sredny Stog culture in the eastern Ukraine he calls the most convincing candidate for the original Indo-European homeland. The Indo-Europeans who remained after the migrations to the west, east and south (as described by Mallory 1989) became speakers of Balto-Slavic, while the speakers of the other satem languages would have to be assigned to the Pit Grave horizon, and the western Indo-Europeans to the Corded Ware horizon. Returning to the Balts and the Slavs, their ancestors should be correlated to the Middle Dnieper culture. Then, following Mallory (197f) and assuming the origin of this culture to be sought in the Sredny Stog, Yamnaya and Late Tripolye cultures, he proposes the course of these events corresponds with the development of a satem language which was drawn into the western Indo-European sphere of influence.

According to Kortlandt, there seems to be a general tendency to date proto-languages farther back in time than is warranted by the linguistic evidence. However, if Indo-Hittite and Indo-European could be correlated with the beginning and the end of the Sredny Stog culture respectively, he states that the linguistic evidence from the overall Indo-European family does not lead us beyond Gimbutas' secondary homeland, so that the Khvalynsk culture on the middle Volga and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus cannot be identified with the Indo-Europeans. Any proposal which goes beyond the Sredny Stog culture must start from the possible affinities of Indo-European with other language families. Taken into account a supposed typological similarity of Proto-Indo-European to the North-West Caucasian languages and assuming this similarity can be attributed to areal factors, Kortlandt thinks of Indo-European as a branch of "Uralo-Altaic" which was transformed under the influence of a Caucasian substratum. Such events would be supported by archaeological evidence and locate the earliest formative phase of Pre-Indo-European north of the Caspian Sea in the 7th millennium (cf. Mallory 1989: 192f.), essentially in agreement with Gimbutas’ theory.

Invasionist vs. diffusionist scenarios

Gimbutas believed that the expansions of the Kurgan culture were a series of essentially hostile, military incursions where a new warrior culture imposed itself on the peaceful, matriarchal cultures of "Old Europe", replacing it with a patriarchal warrior society,[12] a process visible in the appearance of fortified settlements and hillforts and the graves of warrior-chieftains:

- "The process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation. It must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups.[13]"

In her later life, Gimbutas increasingly emphasized the violent nature of this transition from the Mediterranean cult of the Mother Goddess to a patriarchal society and the worship of the warlike Thunderer (Zeus, Dyaus), to a point of essentially formulating feminist archaeology. Many scholars who accept the general scenario of Indo-European migrations proposed, maintain that the transition was likely much more gradual and peaceful than suggested by Gimbutas. The migrations were certainly not a sudden, concerted military operation, but the expansion of disconnected tribes and cultures, spanning many generations. To what degree the indigenous cultures were peacefully amalgamated or violently displaced remains a matter of controversy among supporters of the Kurgan hypothesis.

JP Mallory (in 1989) accepted the Kurgan hypothesis as the de-facto standard theory of Indo-European origins, but he recognizes valid criticism of Gimbutas' radical scenario of military invasion:

One might at first imagine that the economy of argument involved with the Kurgan solution should oblige us to accept it outright. But critics do exist and their objections can be summarized quite simply – almost all of the arguments for invasion and cultural transformations are far better explained without reference to Kurgan expansions, and most of the evidence so far presented is either totally contradicted by other evidence or is the result of gross misinterpretation of the cultural history of Eastern, Central, and Northern Europe."[14]

Criticisms and qualifications

Language does not equal material culture

Linguists argue linguistic expansion does not imply "kurganization" of material cultures, and hold extrapolating current linguistic developments to the past to be precarious (for instance deflexion should be excluded for being a Western European non-representative linguistic process), to conclude a separation between Centum and Satem in the fourth millennium is appropriate but does not imply a different stance on the material cultures involved.[15]

Renfrew's linguistic timedepth

While the Kurgan scenario is widely accepted as one of the leading answers to the question of Indo-European origins, it is still a speculative model and not normative. The main alternative suggestion is the theory of Colin Renfrew and Vyacheslav V. Ivanov, postulating an Anatolian Urheimat, and the spread of the Indo-European languages as a result of the spread of agriculture. This belief implies a significantly older age of the Proto-Indo-European language, 9,000 years as opposed to 6,000, and finds less support among traditional linguists than the Kurgan theory. An argument against the Anatolian Urheimat is that PIE contains words specifically related to cattle-breeding and horse-riding devices invented not earlier than the 5th millennium BC by nomadic tribes in Asian steppes. It is also difficult to correlate the geographical distribution of the Indo-European branches with the advance of agriculture.

A study in 2003 by Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson at the University of Auckland[11] that used a computer analysis based upon lexical data favors an earlier date for Proto-Indo-Europeanca, the 8th millennium, than the Kurgan model does; this earlier date is consistent with Renfrew's Anatolian Urheimat. Their result is based on maximum likelihood analysis of Swadesh lists. Their results run counter to many traditional categorizations of linguistic relations between the different branches within the Indo-European languages tree. However, other computer analysis using different methods and databases support this result. It has been suggested that after originating in Anatolia there may have been a secondary expansion from Eastern Europe, similar to the Kurgan hypothesis.

Occurrence of horse riding in Europe

Renfrew (1999: 268) holds that on the European scene mounted warriors appear only as late as the turn of the second-first millennia BC and these could in no case have been "Gimbutas's Kurgan warriors" predating the facts by some 2,000 years. Mallory (1989, p136) enumerates linguistic evidence pointing to PIE period employment of horses in paired draught, something that would not have been possible before the invention of the spoked wheel and chariot, normally dated after about 2500 BC.

According to Krell (1998), Gimbutas' homeland theory is completely incompatible with the linguistic evidence. Krell compiles lists of items of flora, fauna, economy, and technology that archaeology has accounted for in the Kurgan culture and compares it with lists of the same categories as reconstructed by traditional historical-Indo-European linguistics. Krell finds major discrepancies between the two, and underlines the fact that we cannot presume that the reconstructed term for 'horse', for example, referred to the domesticated equid in the protoperiod just because it did in later times. It could originally have referred to a wild equid, a possibility that would "undermine the mainstay of Gimbutas's arguments that the Kurgan culture first domesticated the horse and used this new technology to spread surrounding areas,"

Pastoralism vs. agriculture

There are several distinct modes of food acquisition in ancient human history. The oldest is the hunter-gatherer mode. In the Neolithic era, people first appear to have cultivated existing plants, and then developed domesticated breeds of plants and animals for food production and other utilitarian purposes (e.g. fiber for clothing). Some Neolithic era and subsequent cultures were sedentary and grew crops. Other Neolithic era and subsequent cultures were pastoral, i.e. they herded domesticated animals as a food source. Tensions between the neighboring herder civilizations and farmer civilizations are documented as far back as written history extends to the Sumerians, and continued into the 19th century in much of the world (e.g. the Indian Wars of the 19th century United States).

Nomadic pastoralism (i.e. nomadic herder civilizations) arose shortly after the development of farming in the Neolithic revolution, possibly through either demic expansion of farming populations with domesticated plants and animals into areas where local environments would not sustain settled farming that abandoned sedentary farming but not domesticated animals, or through cultural diffusion of the tending of domesticated animals to pre-existing hunter-gatherer populations. The demic diffusion model would support an Anatolian origin for Indo-European, as the domesticated species associated with Indo-European societies has its origins in the Near East and Anatolia. In this view, the Kurgans are themselves descendants of Anatolian farmers who would have spoken a proto-Indo-European language and replaced earlier hunter-gatherer populations, prior to serving as a source for many branches of the Indo-European language family. A cultural diffusion model, in contrast, in which Kurgans speaking their own language acquired domesticated herd animals from Antatolia and domesticated horses, then conquered there non-Indo-European speaking Anatolians, would favor a Kurgan hypothesis. (Historical evidence shows that the Turkic languages and Islamic religion that are now present in Anatolia arrived their in the Middle Ages by this route in Turkic and Islamic conquests by nomadic pastoralists, the Kurgan hypothesis would not be unprecedented)

Kathrin Krell (1998) finds that the terms found in the reconstructed Indo-European language are not compatible with the cultural level of the Kurgans. Krell holds that the Indo-Europeans had agriculture whereas the Kurgan people were "just at a pastoral stage" and hence might not have had sedentary agricultural terms in their language, despite the fact that such terms are part of a Prot-Indo-European core vocabulary.

Krell (1998), "Gimbutas' Kurgans-PIE homeland hypothesis: a linguistic critique", points out that the Proto-Indo-European had an agricultural terminology and not merely a pastoral one. As for technology, there are plausible reconstructions suggesting knowledge of navigation, a technology quite atypical of Gimbutas' Kurgan society. Krell concludes that Gimbutas seems to first establish a Kurgan hypothesis, based on purely archaeological observations, and then proceeds to create a picture of the PIE homeland and subsequent dispersal which fits neatly over her archaeological findings. The problem is that in order to do this, she has had to be rather selective in her use of linguistic data, as well as in her interpretation of that data.

Further expansion during the Bronze Age

The Kurgan hypothesis describes the initial spread of Proto-Indo-European during the 5th and 4th millennia BC.[16]

The question of further Indo-Europeanization of Central and Western Europe, Central Asia and Northern India during the Bronze Age is beyond its scope, and far more uncertain than the events of the Neolithic and the Copper Age. The specifics of the Indo-Europeanization of Central and Western Europe during the 3rd to 2nd millennia (Corded Ware horizon) and Central Asia (Andronovo culture) are nevertheless subject to some controversy.

Europe

The European Funnelbeaker and Corded Ware cultures have been described as showing intrusive elements linked to Indo-Europeanization, but recent archaeological studies have described them in terms of local continuity, which has led some archaeologists to declare the Kurgan hypothesis "obsolete".[17] However, it is generally held unrealistic to believe that a proto-historic people can be assigned to any particular group on basis of archaeological material alone.[18]

The Corded Ware culture has always been important in locating the Indo-European origins. The German archaeologist Alexander Häusler was an important proponent of archeologists that searched for homeland evidence here. He sharply criticised Gimbutas' concept of 'a' Kurgan culture that mixes several distinct cultures like the pit-grave culture. Häusler's criticism mostly stemmed from a distinctive lack of archeological evidence until 1950 from what was then the East Bloc, from which time on plenty of evidence for Gimbutas's Kurgan hypothesis was discovered for decades.[19] He was unable to link Corded Ware to the Indo-Europeans of the Balkans, Greece or Anatolia, and neither to the Indo-Europeans in Asia. Nevertheless, establishing the correct relationship between the Corded Ware and Pontic-Caspian regions is still considered essential to solving the entire homeland problem.[20]

Central Asia

See also

- Tumulus

- Yamna culture

- Ukrainian stone stela

- Domestication of the horse

- Animal sacrifice

- Ashvamedha

- Shaft tomb

- Late Glacial Maximum

- Competing hypotheses

- Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

- Armenian hypothesis

- Anatolian hypothesis

- Out of India theory

- Paleolithic Continuity Theory

Notes

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan

- ↑ Mallory (1989:185). "The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total. It is the solution one encounters in the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse."

- ↑ Strazny (2000:163). "The single most popular proposal is the Pontic steppes (see the Kurgan hypothesis)..."

- ↑ Gimbutas (1985) page 190.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Parpola in Blench & Spriggs (1999:181). "The history of the Indo-European words for 'horse' shows that the Proto-Indo-European speakers had long lived in an area where the horse was native and/or domesticated (Mallory 1989:161–63). The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Ukrainian Srednij Stog culture, which flourished c. 4200–3500 BC and is likely to represent an early phase of the Proto-Indo-European culture (Anthony 1986:295f.; Mallory 1989:162, 197–210). During the Pit Grave culture (c. 3500–2800 BC) which continued the cultures related to Srednij Stog and probably represents the late phase of the Proto-Indo-European culture – full-scale pastoral technology, including the domesticated horse, wheeled vehicles, stockbreeding and limited horticulture, spread all over the Pontic steppes, and, c. 3000 BC, in practically every direction from this centre (Anthony 1986, 1991; Mallory 1989, vol. 1).

- ↑ Anthony & Vinogradov (1995)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 [1] The spread of the Indo-Europeans - Frederik Kortlandt, 1989

- ↑ [2] The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology - Timothy Darvill, 2002, Corded Ware, p.101, Oxford University Press, ISBN 019-211649-5

- ↑ Gimbutas (1970) page 156: "The name Kurgan culture (the Barrow culture) was introduced by the author in 1956 as a broader term to replace and Pit-Grave (Russian Yamna), names used by Soviet scholars for the culture in the eastern Ukraine and south Russia, and Corded Ware, Battle-Axe, Ochre-Grave, Single-Grave and other names given to complexes characterized by elements of Kurgan appearance that formed in various parts of Europe"

- ↑ Passarino, G; Cavalleri GL, Lin AA, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Borresen-Dale AL, Underhill PA (2002), "Different genetic components in the Norwegian population revealed by the analysis of mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms", Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10 (9): 521–9, doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200834, PMID 12173029, http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v10/n9/full/5200834a.html.

- ↑ Dupuy, B. et al. 2006. Geographical heterogeneity of Y-chromosomal lineages in Norway. Forensic Science International. 164: 10-19.

- ↑ Gimbutas (1982:1)

- ↑ Gimbutas, Dexter & Jones-Bley (1997:309)

- ↑ Mallory (1991:185)

- ↑ Frederik Kortlandt, Professor of descriptive and comparative linguistics, University of Leiden - unpublished communication, may 2007

- ↑ The New Encyclopedia Britannica, 15th edition, 22:587-588

- ↑ Pre- & protohistorie van de lage landen, onder redactie van J.H.F. Bloemers & T. van Dorp 1991. De Haan/Open Universiteit. ISBN 90 269 4448 9, NUGI 644

- ↑ The Germanic Invasions, the making of Europe 400-600 AD - Lucien Musset, ISBN 1-56619-326-5, p7

- ↑ Schmoeckel 1999

- ↑ In Search of the Indo-Europeans - J.P.Mallory, Thames and Hudson 1989, p245,ISBN 0-500-27616-1

References

- Anthony, David; Vinogradov, Nikolai (1995), "Birth of the Chariot", Archaeology 48 (2): 36–41.

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew, eds. (1999), Archaeology and Language, III: Artefacts, languages and texts, London: Routledge.

- Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Jones-Bley, Karlene, eds. (1997), The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles From 1952 to 1993, Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0-941694-56-9.

- Gimbuta, Marija (1956). The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Part 1.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1970), "Proto-Indo-European Culture: The Kurgan Culture during the Fifth, Fourth, and Third Millennia B.C.", in Cardona, George; Hoenigswald, Henry M.; Senn, Alfred, Indo-European and Indo-Europeans: Papers Presented at the Third Indo-European Conference at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 155–197, ISBN 0812275748.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1982), "Old Europe in the Fifth Millenium B.C.: The European Situation on the Arrival of Indo-Europeans", in Polomé, Edgar C., The Indo-Europeans in the Fourth and Third Millennia, Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers, ISBN 0897200411

- Gimbutas, Marija (Spring/Summer 1985), "Primary and Secondary Homeland of the Indo-Europeans: comments on Gamkrelidze-Ivanov articles", Journal of Indo-European Studies 13 (1&2): 185–201

- Gimbutas, Marija; Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Jones-Bley, Karlene (1997), The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles from 1952 to 1993, Washington, D. C.: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0941694569

- Gimbutas, Marija; Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1999), The Living Goddesses, Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0520229150

- Krell, Kathrin (1998). "Gimbutas' Kurgans-PIE homeland hypothesis: a linguistic critique". Chapter 11 in "Archaeology and Language, II", Blench and Spriggs.

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q., eds. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, London: Fitzroy Dearborn, ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

- Mallory, J.P. (1991), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- Mallory, J.P. (1996), Fagan, Brian M., ed., The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-507618-4

- Schmoeckel, Reinhard (1999), Die Indoeuropäer. Aufbruch aus der Vorgeschichte ("The Indo-Europeans: Rising from pre-history"), Bergisch-Gladbach (Germany): Bastei Lübbe, ISBN 3404641620

- Strazny, Philipp (Ed). (2000), Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics (1 ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-1579582180

- Zanotti, D. G. (1982), "The Evidence for Kurgan Wave One As Reflected By the Distribution of 'Old Europe' Gold Pendants", Journal of Indo-European Studies 10: 223–234.