Lingzhi mushroom

| Ganoderma lucidum | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Phylum: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Polyporales |

| Family: | Ganodermataceae |

| Genus: | Ganoderma |

| Species: | G. lucidum |

| Binomial name | |

| Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst |

|

| Ganoderma lucidum | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| pores on hymenium | |

|

cap is offset or indistinct |

|

| hymenium attachment is irregular or not applicable | |

|

stipe is bare or lacks a stipe |

|

| spore print is brown | |

|

ecology is saprotrophic or parasitic |

|

| edibility: edible | |

| Lingzhi mushroom | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 靈芝 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 灵芝 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||

| Kana | レイシ | ||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 靈芝 | ||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 霊芝 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||

| Hangul | 영지 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Língzhī (traditional Chinese: 靈芝; simplified Chinese: 灵芝; Japanese: reishi; Korean: yeongji, hangul: 영지) is the name for one form of the mushroom Ganoderma lucidum, and its close relative Ganoderma tsugae. Ganoderma lucidum enjoys special veneration in Asia, where it has been used as a medicinal mushroom in traditional Chinese medicine for more than 4,000 years[1], making it one of the oldest mushrooms known to have been used in medicine.

The word lingzhi, in Chinese, means "herb of spiritual potency" and has also been described as "mushroom of immortality".[1] Because of its presumed health benefits and apparent absence of side-effects, it has attained a reputation in the East as the ultimate herbal substance. Lingzhi is listed in the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia and Therapeutic Compendium.

Contents |

Taxonomy and naming

The name Ganoderma is derived from the Greek ganos/γανος "brightness, sheen", hence "shining" and derma/δερμα "skin",[2] while the specific epithet lucidum in Latin for "shining" and tsugae refers to being of the Hemlock (Tsuga). Another Japanese name is mannentake (万年茸), meaning "10,000 year mushroom".

There are multiple species of lingzhi, scientifically known to be within the Ganoderma lucidum species complex and mycologists are still researching the differences between species within this complex of species.[3]

Description

Lingzhi is a polypore mushroom that is soft (when fresh), corky, and flat, with a conspicuous red-varnished, kidney-shaped cap and, depending on specimen age, white to dull brown pores underneath.[1] It lacks gills on its underside and releases its spores through fine pores, leading to its morphological classification as a polypore.

Varieties

Ganoderma lucidum generally occurs in two growth forms, one, found in North America, is sessile and rather large with only a small or no stalk, while the other is smaller and has a long, narrow stalk, and is found mainly in the tropics. However, many growth forms exist that are intermediate to the two types, or even exhibit very unusual morphologies,[1] raising the possibility that they are separate species. Environmental conditions also play a substantial role in the different morphological characteristics lingzhi can exhibit. For example, elevated carbon dioxide levels result in stem elongation in lingzhi. Other forms show "antlers', without a cap and these may be affected by carbon dioxide levels as well.

According to Compendium of Materia Medica, lingzhi may be classified into six categories according to their shapes and colors, each of which is believed to nourish a different part of the body. (Red-heart, Purple-joints, Green-liver, White-lungs/skin, Yellow-spleen, Black-kidneys/brain).

Biochemistry

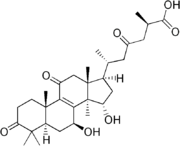

Ganoderma lucidum produces a group of triterpenes, called ganoderic acids, which have a molecular structure similar to steroid hormones.[4] It also contains other compounds many of which are typically found in fungal materials including polysaccharides such as beta-glucan, coumarin, mannitol, and alkaloids.[4]

Habitat

Ganoderma lucidum, and its close relative Ganoderma tsugae, grow in the northern Eastern Hemlock forests. These two species of bracket fungus have a worldwide distribution in both tropical and temperate geographical regions, including North and South America, Africa, Europe, and Asia, growing as a parasite or saprotroph on a wide variety of trees.[1] Similar species of Ganoderma have been found growing in the Amazon.[5] In nature, Lingzhi grows at the base and stumps of deciduous trees, especially maple.[6] Only two or three out of 10,000 such aged trees will have Lingzhi growth, and therefore its wild form is generally rare. Today, Lingzhi is effectively cultivated both indoors under sterile conditions and outdoors on either logs or woodchip beds.

History

Shen Nong's Herbal Classic, a 2000-year old medicinal Chinese text [2] states "The taste is bitter, its energy neutral, it has no toxicity. It cures the accumulation of pathogenic factors in the chest. It is good for the Qi of the head, including mental activities... Long term consumption will lighten the body; you will never become old. It lengthens years."

Bencao Gangmu ("Great Pharmacopoeia"), a Chinese medical book published in the 16th century, also shows a possible link between modern research and folk knowledge when describing the Lingzhi mushroom: "It positively affects the Qi of the heart, repairing the chest area and benefiting those with a knotted and tight chest. Taken over a long period of time agility of the body will not cease, and the years are lengthened..."[3]

Depictions of the Lingzhi mushroom as a symbol for health, are shown in many places of the Emperors residences in the Forbidden City as well as the Summer Palace.[4] The Chinese goddess of healing Guan Yin is sometimes depicted holding a Lingzhi mushroom.

Lingzhi research and therapeutic usage

Lingzhi may possess anti-tumor, immunomodulatory and immunotherapeutic activities, supported by studies on polysaccharides, terpenes, and other bioactive compounds isolated from fruiting bodies and mycelia of this fungus (reviewed by R. R. Paterson[4] and Lindequist et al.[7]). It has also been found to inhibit platelet aggregation, and to lower blood pressure (via inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme[8]), cholesterol, and blood sugar.[9]

Laboratory studies have shown anti-neoplastic effects of fungal extracts or isolated compounds against some types of cancer. In an animal model, Ganoderma has been reported to prevent cancer metastasis,[10] with potency comparable to Lentinan from Shiitake mushrooms.[11]

The mechanisms by which G. lucidum may affect cancer are unknown and they may target different stages of cancer development: inhibition of angiogenesis (formation of new, tumor-induced blood vessels, created to supply nutrients to the tumor) mediated by cytokines, cytoxicity, inhibiting migration of the cancer cells and metastasis, and inducing and enhancing apoptosis of tumor cells.[4] Nevertheless, G. lucidum extracts are already used in commercial pharmaceuticals such as MC-S for suppressing cancer cell proliferation and migration.

Additional studies indicate that ganoderic acid can help to strengthen the liver against liver injury by viruses and other toxic agents in mice, suggesting a potential benefit of this compound in the prevention of liver diseases in humans,[12] and Ganoderma-derived sterols inhibit lanosterol 14α-demethylase activity in the biosynthesis of cholesterol .[13] Ganoderma compounds inhibit 5-alpha reductase activity in the biosynthesis of dihydrotestosterone.[8]

Besides effects on mammalian physiology, Ganoderma is reported to have anti-bacterial and anti-viral activities.[14][15] Ganoderma is reported to exhibit direct anti-viral with the following viruses; HSV-1, HSV-2, influenza virus, vesicular stomatitis. Ganoderma mushrooms are reported to exhibit direct anti-microbial properties with the following organisms; Aspergillus niger, Bacillus cereus, Candida albicans, and Escherichia coli.

Preparation

Due to its bitter taste, Lingzhi is traditionally prepared as a hot water extract.[5] Thinly sliced or pulverized lingzhi (either fresh or dried) is added to a pot of boiling water, the water is then brought to a simmer, and the pot is covered; the lingzhi is then simmered for two hours. The resulting liquid is fairly bitter in taste, with the more active red lingzhi more bitter than the black. The process is sometimes repeated. Alternatively, it can be used as an ingredient in a formula decoction or used to make an extract (in liquid, capsule, or powder form). The more active red forms of lingzhi are far too bitter to be consumed in a soup.

See also

- Medicinal mushrooms

- Smith JE, Rowan NJ, Sullivan R Medicinal Mushrooms: Their Therapeutic Properties and Current Medical Usage with Special Emphasis on Cancer Treatments Cancer Research UK, 2001

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 David Arora (1986). Mushrooms demystified, 2nd edition. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ R. S. Hseu, H. H. Wang, H. F. Wang and J. M. Moncalvo (1 April 1996). "Differentiation and grouping of isolates of the Ganoderma lucidum complex by random amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR compared with grouping on the basis of internal transcribed spacer sequences" (Abstract). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62 (4): 1354–1363. PMID 8919797. http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/62/4/1354.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Paterson RR (2006). "Ganoderma - a therapeutic fungal biofactory". Phytochemistry 67: 1985–2001. doi:10.1002/chin.200650268.)

- ↑ Medicinal Mushrooms: An Exploration of Tradition, Healing, & Culture (Herbs and Health Series)by Christopher Hobbs (Author), Harriet Beinfield

- ↑ (National Audubon Society; Field guide to Mushrooms,1993)

- ↑ Lindequist U, Niedermeyer THJ, Jülich WD. (2005). "The pharmacological potential of mushrooms". Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2 (3): 285–299. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh107. http://ecam.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/2/3/285.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Liu J, Kurashiki K, Shimizu K, Kondo R (December 2006), "Structure-activity relationship for inhibition of 5alpha-reductase by triterpenoids isolated from Ganoderma lucidum", Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14 (24): 8654–60, doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.08.018, PMID 16962782

- ↑ Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition by Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stoger, and Andrew Gamble (2004)

- ↑ Lee, SS., Chen, FD., Chang, SC., et al. (1984). In vivo anti-tumor effects of crude extracts from the mycelium of Ganoderma lucidum. J. of Chinese Oncology Society 5(3): 22-28.

- ↑ Suga, T., Shiio, T., Maeda, YY., Chihara, G. (1994). Anti tumor activity of lenytinan in murine syngeneic and autochthonous hosts and its suppressive effect on 3 methylcholanthrene induced carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 44:5132-

- ↑ Li YQ, Wang SF (2006). "Anti-hepatitis B activities of ganoderic acid from Ganoderma lucidum". Biotechnol. Lett. 28: 837–841. doi:10.1007/s10529-006-9007-9.

- ↑ Hajjaj H, Macé C, Roberts M, Niederberger P, Fay LB (July 2005). "Effect of 26-oxygenosterols from Ganoderma lucidum and their activity as cholesterol synthesis inhibitors". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 (7): 3653–8. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.7.3653-3658.2005. PMID 16000773.

- ↑ Wang H, Ng TB (January 2006). "Ganodermin, an antifungal protein from fruiting bodies of the medicinal mushroom Ganoderma lucidum". Peptides 27 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2005.06.009. PMID 16039755.

- ↑ Moradali MF, Mostafavi H, Hejaroude GA, Tehrani AS, Abbasi M, Ghods S (2006). "Investigation of potential antibacterial properties of methanol extracts from fungus Ganoderma applanatum". Chemotherapy 52 (5): 241–4. doi:10.1159/000094866. PMID 16899973.

Further reading

- Xie, J.T.; Wang, C.Z.; Wicks, S.; Yin, J.J.; Kong, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.C.; Yuan, C.S. (2006). "Ganoderma lucidum extract inhibits proliferation of SW 480 human colorectal cancer cells". Exp Oncol 28 (1): 25–9. PMID 1661470. http://www.exp-oncology.com.ua/en/archives/25/490.html.

- Müller, C.I.; Kumagai, T.; O’kelly, J.; Seeram, N.P.; Heber, D.; Koeffler, H.P. (2006). "Ganoderma lucidum causes apoptosis in leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma cells". Leukemia Research 30 (7): 841–848. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2005.12.004.

- Gao, Y.; Tang, W.; Dai, X.; Gao, H.; Chen, G.; Ye, J.; Chan, E.; Koh, H.L.; Li, X.; Zhou, S. (2005). "Effects of water-soluble Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides on the immune functions of patients with advanced lung cancer". J Med FoodTimo H. J. 8 (2): 159–168. doi:10.1089/jmf.2005.8.159.

- Lindequist, U.; Niedermeyer, T.H.J. ; Jülich, W.D. (2005). "The pharmacological potential of mushrooms.". Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh107. PMID 16136207. http://ecam.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/2/3/285.

- Tanaka, S.; Ko, K.; Kino, K.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yamashita, A.; Murasugi, A.; Sakuma, S.; Tsunoo, H. (1989). "Complete amino acid sequence of an immunomodulatory protein, ling zhi-8 (LZ-8). An immunomodulator from a fungus, Ganoderma lucidum, having similarity to immunoglobulin variable regions.". J. Biol. Chem.. PMID 2570780. http://www.jbc.org/content/264/28/16372.long5.

- Murasugi, A.; Tanaka, S.; Komiyama, N.; Iwata, N.; Kino, K.; Tsunoo, H.; Sakuma, S. (1991). "Molecular cloning of a cDNA and a gene encoding an immunomodulatory protein, Ling Zhi-8, from a fungus, Ganoderma lucidum.". J. Biol. Chem.. PMID 1990000. http://www.jbc.org/content/266/4/2486.long.