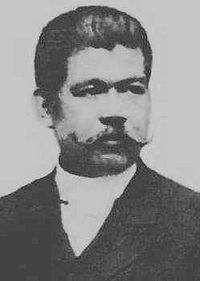

Marcelo H. del Pilar

| Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitan | |

|---|---|

Marcelo H. del Pilar |

|

| Born | August 30, 1850 Cupang, Bulacan, Bulacan, Philippines |

| Died | July 4, 1896 (aged 46) Barcelona, Spain |

| Nationality | |

| Other names | Plaridel, Dolores Manapat, Carmelo, Puhdoh, Piping Dilat, L.O Crame |

| Occupation | Writer, Journalist, Lawyer, Newspaperman, and Poet |

| Known for | La Solidaridad and Propaganda Movement |

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitan (August 30, 1850 – July 4, 1896) was a Filipino writer, journalist, and revolutionary leader of the Philippine Revolution and one of the leading Ilustrado (Knowledgeable[1][2]) propagandist of the Philippine War of Independence.[3]

He served as editor of the vernacular section of the Diariong Tagalog (Tagalog Newspaper), the first Philippine bilingual newspaper, in 1882. From 1890 to around 1895, he edited and published the newspaper La Solidaridad (Solidarity), mainly through his 150 essays and 66 editorials published under the nom de plume Plaridel.[4]

Del Pilar's militant and progressive outlook was derived from the classic enlightenment tradition of the French philosophes and the scientific empiricism of the European bourgeoisie. Part of this outlook was transmitted by freemasonry, to which del Pilar subscribed.[5]

Contents |

Biography

Early life and education

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitan was born in sitio Cupang, Bulacan, Bulacan, on August 30, 1850, to Don Julián Hilario del Pilar, a three time gobernadorcillo and a poet-grammarian, and Doña Blasa Gatmaitan.[6] He was the last child and the fifth son among the ten children and was baptized Marcelo Hilario. Because there were many children in the family, Marcelo gave up his share of his inheritance for his other brothers and sisters. His elder brother, Fr. Toribio del Pilar, was exiled to Guam for his involvement in the 1872 Cavite Mutiny. The family adapted the surname Del Pilar in 1849 pursuant on the decree issued by Governor-General Narciso Claveria.[7] Del Pilar was descended from the illustrious lineage of Gatmaitan, one of the sons of the pre-colonial ruling families of Bulacan and Pampanga.

He learned his first letters from his paternal uncle Alejo in 1860. Because his family was highly cultured, it was not long before he played the piano, violin, and flute. In Manila he took a Latin course in the school of José A. Flores in 1872 and then transferred at the Colegio de San José, where he finished his Bachelor of Arts degree. He also studied at the University of Santo Tomas, where he obtained his law degree.[6] Reliable information on his years as a student is incomplete, though he clearly dropped out of law school a couple times, finishing degree only in 1881. This was due to a dispute with a parish priest of San Miguel, Manila in 1869 who was charging an exorbitant baptismal fee.[6]

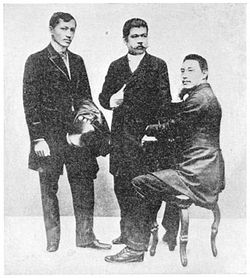

As a student, he favored overthrowing the Spanish government. Often, he met with his classmates like Mariano Ponce, Numeriano Adriano, Pedro Serrano Laktaw, and Apolinario Mabini in his Binondo house, and expounded on the need to peacefully fight Spanish rule. His mastery of Spanish language would help hasten development led him to teach Spanish to children in his neighborhood while he was a boarder of Mariano Sevilla, a Filipino secular priest. Then about the time of Cavite Mutiny, he used to meet regularly in a goods store in Manila with liberal Spanish creoles, mestizos, and Filipino intellectuals by whom he was politically indoctrinated about the affairs of the country.[8] Fortunately, suspicion was not turned on him and he escaped prosecution in 1872.

He worked as oficial de mesa in Pampanga and Quiapo in January 1878. He worked for the Manila Royal Audiencia and at the same time he spread nationalist and anti-friar ideas in Manila and in towns and barrios of Bulacan. He married his second cousin Marciana (Tsanay) in February 1878. They had seven children and five died of infancy. Already a family man, he finally obtained his licentiate in jurisprudence in 1880.

Publications assailing the Spanish friars

Driven by his sense of justice and his own bad experiences with the clergy, del Pilar denounced in his publications on the violations of the clergy, the narrow-mindedness and hypocrisy. He made speeches in an open crowd, whether a cockpit, tienda, and town plaza. He delivered his tirades against the friars during fiestas, parties and funeral wakes. He wrote poems and essays defending Filipino interests and fought for the equality of Filipinos and Spaniards in his book "La Soberania Monacal en Filipinas" (Monastic Sovereignty in the Philippines).[9]

Published in 1888 under his pseudonym, Plaridel, he underscores the failure of government in making good the noble promises of the first encounter between Spain and the Philippines, formalized by an agreement sealed with the blood of Legazpi and Sikatuna. The shortcomings of government are capitalized on by the friars to secure their temporal powers, promote their material interests and perpetuate themselves as the sole arbiters of spiritual and earthly matters in the Philippines; in effect, establishing a monastic rule.[9]

On August 1, 1882, del Pilar founded the newspaper Diariong Tagalog (Tagalog Newspaper), with the help of Francisco Calvo y Muñoz, a wealthy Spanish liberal. This newspaper was the first to publish ideas for reforms in the Philippines. Editing its Tagalog section, he published among others, his nationalist and reformist articles, like the Tagalog translation of Rizal's El amor patrio. When lack of funds forced him to stop publication on October 31, 1882, he produced pamphlets making fun of friars, such as Dasalan at Tocsohan (Prayerbook and Teasing Game), Pasióng Dapat Ipag-alab nang Puso nang Tauong Babasa (Passion That Should Inflame the Heart of the Reader), Caiingat Cayo (Be Careful), Cadacilaan ng Dios (God's Goodness), Sagot ng España sa Hibik ng Pilipinas (Spain's Reply to the Complains of Filipinos), Dudas (Doubts) and La Frailocracia Filipina (Frailocracy in the Philippines).[10][11] All were published in Madrid in 1889.

His parodies of the Our Father, the Hail Mary, the Apostle's Creed, the Ten Commandments and the catechism published in pamphlets which simulated the format and size of the novenas were highly effective propaganda. Unlike Rizal, who wrote his novels in Spanish, del Pilar wrote his propaganda pamphlets in simple Tagalog.

Escape from clerical prosecution

He organized with Doroteo Cortes, José Ramos, and Juan Zulueta various anti-friar demonstrations, culminating in March 1888 when he joined a demonstration in Manila and sought audience with the governor-general, demanding the expulsion of friars from the Philippines and the exile of the archbishop. On August 3 of the same year, del Pilar writing under the name Dolores Manapat wrote a pamphlet in answer to Fr. José Rodriguez's work which he entitled ¡CAIÑGAT CAYO!.[12]

Del Pilar became a wanted man; the friars wielded their influence to secure an order of banishment against him. When the order was finally released, del Pilar had already fled to Spain. Before his departure, he organized Caja de Jesus, María y José intended to provide scholarship grants to poor but intelligent children and the Junta de Programa, which functioned to collect funds to support the propaganda work and constitute liaison between the propagandists in Spain and those in the Philippines.

On October 28, 1888, del Pilar left Manila for Spain, and spent his time with the Filipinos in Hong Kong led by José María Basa, a propagandist and a bitter enemy of the clergy. Basa - whom Rizal had already established contact on his way back to Europe - became the agent for smuggling Rizal's novels into the Philippines.

Life in Spain

In the same year, on the flight from the pursuit through the clergy, del Pilar went to Spain arriving in Barcelona on January 1, 1889. Del Pilar succeeded Graciano López Jaena as the editor of the newspaper La Solidaridad on December 15, 1889.[13][14] Even before del Pilar had chief burden of the editorship, and when he assumed the post, he transferred the editorial office from Barcelona to Madrid.

The newspaper busied itself with the moderated goals of the representative of the Philippines in the Spanish parliament. It entered for the legal comparison of Spaniards and Filipinos and the lifting of the polo (community service) and the bandala (the compulsion sale of local products at the government). The newspaper demanded moreover a guarantee of the basic rights of speech freedom and society freedom as well as same for Filipinos and Spaniards, who wanted to enter into the civil service.

Del Pilar succeeded the goals of the leaf to promote, in that it contacted liberal Spaniards, that were sympathetic to Filipinos. Under it expanded themselves the demands of the newspaper, active cooperation of Filipino in matters of the government, speech freedom, press freedom and meeting freedom, would extend social and political independences, equivalence before the court, reception of a representation in the Spanish Cortes or the parliament.

Del Pilar came however soon in difficulties and these reached its highpoint when the money means were exhausted for the support of its newspaper. Simultaneously there was no sign at all of a direct reaction that would place a support of sides of the Spanish ruler class in outlook.[13] Before its death, that was favored by hunger and large need, del Pilar abandoned its bearing to the assimilation and began with the planning of an armed revolt.[2]

It strengthened this conviction through following lines:

Insurrection is the last remedy, especially when the people have acquired the belief that peaceful means to secure the remedies for evils prove futile.

This idea was an inspiration for Andrés Bonifacio of Katipunan, a secret revolutionary organization which aimed to gained independence from Spain.[13]

Rizal's Spanish biographer Wenceslao Retana and Filipino biographer Juan Raymundo Lumawag saw the formation of the Katipunan as Del Pilar's victory over Rizal: "La Liga dies, and the Katipunan rises in its place. Del Pilar's plan wins over that of Rizal. Del Pilar and Rizal had the same end, even if each took a different road to it."

Later years and death

Del Pilar left his wife and two daughters in the Philippines when he went to Spain in. Marciana, his wife, worked hard to support Sofia and Anita. Del Pilar could not afford to send any money to his family since he himself was penniless.[15] After years of publication from 1889 to 1895, La Solidaridad had begun to run out of funds without accomplishing concrete changes in the Philippines. Its last issue appeared on November 15, 1895.[4]

In the early months of 1896, however del Pilar and Ponce decided to return in Hongkong. In Barcelona, del Pilar was overtaken by increasing bad health of past year or more. After several months of illness, del Pilar died of tuberculosis in a public hospital in Barcelona on July 4, 1896 at the age of 46. The following day, he was buried in unmarked grave at the Cementerio del Sud-Oeste. He left with his friend Fernando Canon a message for his daughter, saying that he had received the sacraments of the church before he died. López Jaena had died six months earlier in Barcelona in a similar hospital run by the Sisters of Charity, and is said to have retracted masonry and received the sacraments as Del Pilar did. A few months after his death, the revolution broke out.[13]

His remains were brought back in 1920 to his final resting place, now known as Dambana ni Plaridel under the National Historical Institute located in San Nicolas, Bulacan, Bulacan.

Father of Philippine Masonry

Considered the Father of Philippine Masonry, del Pilar spearheaded the secret organization of Masonic lodges in the Philippines as a means of strengthening the Propaganda Movement.

He was made a freemason in Spain in 1889, one of the first Filipinos initiated into the mysteries of freemasonry in Europe. He co-founded Lodge Revoluccion in Barcelona and revived Lodge Solidaridad 53 when it floundered into stormy seas where he became its Worshipful Master and with Rizal as the orator. He was crowned 33° by the Gran Oriente Español.[5]

Legacy

Organized in his memory, Samahang Plaridel is a fellowship of journalists and other communicators that aims to propagate Marcelo H. del Pilar’s ideals.

This fellowship fosters within its capacity, mutual help, cooperation, and assistance among its members; dedicated to the journalistic standards of accuracy and truth, and in promoting these standards in the practice of journalism. Plaridel’s ideology of truth, fairness and impartiality is anchored on democratic principles, as these are the bastions of a society acceptable to all Filipinos.

See also

- Filipino nationalism

- La Solidaridad

- Propaganda Movement

- Philippine Revolution

References

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley. In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, Ballantine Books, Random House, Inc., March 3, 1990, 536 pages, page 15. - ISBN 0-345-32816-7

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Glossary: Philippines, Area Handbook Series, Country Studies, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, LOC.gov (undated), retrieved on: July 30, 2007

- ↑ De Guzman, Maria O. (1967). The Filipino Heroes. National Bookstore, Inc.. ISBN 971-08-2987-4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "La Solidaridad and La Liga Filipina". Philippine-History.org. http://www.philippine-history.org/la-solidaridad.htm. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Famous Filipino Mason - Marcelo H. Del Pilar". Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of the Philippines. http://www.glphils.org/famous-masons/fmhdelpilar.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Zaide, Gregorio F. (1984). Philippine History and Government. National Bookstore Printing Press.

- ↑ "Historical Events in the Philippines". Geotayo.com. http://www.geotayo.com/history365.php. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ↑ "Liberalism in the Philippines". sspxasia.com. http://www.sspxasia.com/Newsletters/2002/Jan-Mar/Liberalism_in_the_Philippines.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "La Soberania Monacal en Filipinas - Pilar, Marcelo H. del". Filipiniana.Net. http://www.filipiniana.net/wbookday.jsp. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ La Frailocracia Filipina (Barcelona: Imprenta Iberica de Francisco Fossas, 1889) was published under del Pilar's pen name Plaridel.[1]

- ↑ As the word frailocracia cannot be found in most Spanish dictionaries nor the word “frailocracy” in the English, the term must have been coined by succeeding Filipino writers to refer to this 'unique' system of government

- ↑ Dolores Manapat, Caiingat Cayó (Manila, 1888), reproduced in Santos, Philippine Review, 3:961-63 [2]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Schumacher, John N. (1973). The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: the creation of a Filipino consciousness (1997 ed.). Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 333. ISBN 9789715502092. http://books.google.com/books?id=6GU_Tzxu5qoC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Ganzon, Guadalupe Fores (1997). La Solidaridad. Makati City. ISBN 971-91655-6-1.

- ↑ Rene O. Villanueva, Student's Philippine Almanac 1st edition (Quezon City: Filway Marketing, 1991). p. 374

External links

- "Philippine History - Plaridel." http://www.msc.edu.ph/centennial/mhpilar.html

- "Bulacan, Philippines: Tourism: Marcelo H. del Pilar Shrine." http://www.bulacan.gov.ph/tourism/touristspot.php?id=32

- "Short Biography" http://www.bookrags.com/biography/marcelo-hilario-del-pilar/

- Caiñgat Cayo! original image scans of the pamphlet written in 1889.

- "The Philippine Revolution: La Solidaridad." http://www.msc.edu.ph/centennial/solidaridad.html (accessed on July 10, 2007).

|

||||||||||||||