Mir

|

||

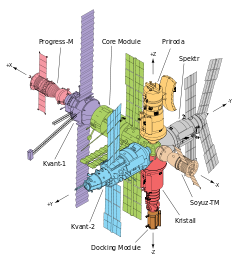

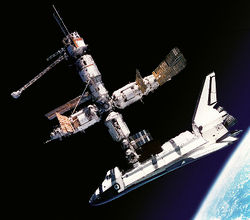

| Mir on 26 September 1996 as seen from the departing Space Shuttle Atlantis during STS-79. | ||

|

||

| Mir insignia. | ||

| Station statistics | ||

|---|---|---|

| NSSDC ID | 1986-017A | |

| Call sign | Mir | |

| Crew | 3 | |

| Launch | 1986–1996 | |

| Launch pad | LC-200/39, and LC-81/23, Baikonur Cosmodrome LC-39A, Kennedy Space Center |

|

| Reentry | 23 March 2001 05:59 UTC |

|

| Mass | 129,700 kg (285,940 lbs) |

|

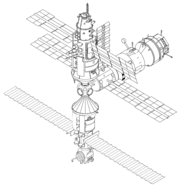

| Length | 31 m (101.7 ft) from Priroda to the docking module |

|

| Width | 27.5 m (90.2 ft) from Kvant-2 to Spektr |

|

| Height | 19 m (62.3 ft) from Kvant-1 to the core module |

|

| Pressurised volume | 350 m³ | |

| Perigee | 350 km (189 nmi) AMSL (August 1993) |

|

| Apogee | 400 km (216 nmi) AMSL (August 1993) |

|

| Orbital inclination | 51.6 degrees | |

| Orbital period | 88.15 minutes | |

| Orbits per day | 16.34 | |

| Days in orbit | 5,519 days | |

| Days occupied | 4,592 days | |

| Number of orbits | c.86,331 | |

| Statistics as of 23 March 2001 (unless noted otherwise) |

||

| References: [1][2][3][4][5] | ||

| Configuration | ||

|

||

| Station elements as of May 1996. | ||

Mir (Russian: Мир; lit. Peace or World) was a Soviet and later Russian space station, operational in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001. With a greater mass than that of any previous space station, Mir was the first of the third generation type of space station, constructed from 1986 to 1996 with a modular design, and was the largest artificial satellite orbiting the Earth until its deorbit on 21 March 2001, a record now surpassed by the International Space Station (ISS). Mir served as a microgravity research laboratory in which crews conducted experiments in biology, human biology, physics, astronomy, meteorology and spacecraft systems, with an aim to develop technologies required for the permanent occupation of space. The station was the first consistently inhabited long-term research station in space, and was operated by a series of long-duration crews. The Mir programme currently holds the record for the longest uninterrupted human presence in space, at 9 years and 257 days, and for the longest single human spaceflight, of Valeri Polyakov, at 437 days 18 hours. Mir was occupied for a total of twelve and a half years of its fifteen-year lifespan, having the capacity to support a resident crew of three but could also support larger crews for short-term visits.

Following the success of the Salyut programme, Mir represented the next stage in the Soviet Union's space station programme. The first module of the station, known as the base block, was launched in 1986, and was followed by six further modules, all being launched by Proton rockets (with the exception of the docking module). When complete, the station consisted of seven pressurised modules and several unpressurised components. Power was provided by several solar arrays mounted directly to the modules.

Through a number of international collaborations, including Intercosmos, Euromir and the Shuttle-Mir programme, the station was made accessible to astronauts from North America, several western European nations, Japan as well as cosmonauts from various eastern nations. Mir also marked the beginning of space tourism when Japanese journalist Toyohiro Akiyama made a paid visit in 1990.

Contents |

Origins

Mir was authorized as part of the third generation of Soviet space systems in a February 17, 1976 decree to design an improved model of the Salyut DOS-17K space station. Four Salyut space stations had already been launched since 1971, with three more being launched during Mir's development. It was planned that the base blocks (DOS-7 and DOS-8) would be equipped with a total of four docking ports; two at either end of the station as with the Salyut stations, and an additional two ports on either side of a docking sphere at the front of the station. By August 1978, this had evolved to the final configuration of one aft port and five ports in a spherical compartment at the forward end of the station.[6]

It was originally planned that the ports would connect to 7.5 tonne modules derived from the Soyuz spacecraft. These modules would have used a Soyuz propulsion module, as in Soyuz and Progress, and descent module and orbital module would have been replaced with a long laboratory module.[6] However, following a February 1979 governmental resolution, the program was consolidated with Vladimir Chelomei's manned Almaz military space station program. The docking ports were reinforced to accommodate 20 tonne space station modules based on the TKS spacecraft. NPO Energia was responsible for the overall space station, with work subcontracted to KB Salyut, due to ongoing work on the Energia launch vehicle and Salyut 7, Soyuz-T, and Progress spacecraft. KB Salyut began work in 1979, and drawings were released in 1982 and 1983. New systems incorporated into the station included the Salyut 5B digital flight control computer and gyrodyne flywheels (taken from Almaz), Kurs automatic rendezvous system, Altair satellite communications system, Elektron oxygen generators, and Vozdukh carbon dioxide scrubbers.[6]

By early 1984 work on Mir had ground to a halt while all resources were being put into the Buran program in order to prepare the Buran space shuttle for flight testing. Funding was returned in early 1984 when Valentin Glushko was ordered by the Central Committee's Secretary for Space and Defense to orbit Mir by early 1986, in time for the 27th Communist Party Congress.[6]

It was clear that the planned processing flow could not be followed and still make the 1986 launch date. It was decided on Cosmonaut's Day (April 12) to ship the flight model of the base block to the Baikonur cosmodrome and conduct the systems testing and integration there. The module arrived at the launch site on May 6, 1985. 1100 of 2500 cables required rework based on the results of tests to the ground test model at Khrunichev. In October the base block was rolled outside its cleanroom. The first launch attempt on February 16, 1986 was scrubbed when the spacecraft communications failed, but the second launch attempt, on February 19, 1986 at 21:28:23 UTC, was successful, meeting the political deadline.[6]

Station structure

Pressurised modules

In its completed configuration, the space station consisted of seven different modules, each launched into orbit separately over a period of ten years by either Proton rocket or Space Shuttle.

| Module | Soyuz | Launch date | Launch system | Nation | Isolated View | Station View |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mir (Core Module) |

N/A | February 19, 1986 | Proton-K | Soviet Union | ||

| The base block for the entire Mir complex, the core module provided the main living quarters for resident crews, environmental systems, provided early attitude control systems and contained the station's main engines. The module consisted of a stepped-cylinder main compartment and a spherical docking module to which served as an airlock and provided ports to which four of the station's expansion modules were berthed, and to which a Soyuz or Progress spacecraft could dock. The module's aft port served as the berthing location for Kvant-1.[7] | ||||||

| Kvant-1 (Astrophysics Module) |

TM-2 | March 31, 1987 | Proton-K | Soviet Union |  |

|

| The first expansion module to be launched, Kvant-1 consisted of two pressurized working compartments and one unpressurised experiment compartment. Scientific equipment included an X-ray telescope, an ultraviolet telescope, a wide-angle camera, high-energy X-ray experiments, an X-ray/gamma ray detector, and the Svetlana electrophoresis unit. The module also carried six gyrodines for attitude control, life support systems including an Elektron oxygen generator and Vozdukh carbon dioxide scrubber.[7] | ||||||

| Kvant-2 (Augmentation Module) |

TM-8 | November 26, 1989 | Proton-K | Soviet Union |  |

|

| The first TKS based module, Kvant-2 was divided into three compartments; an EVA airlock, instrument/cargo compartment (which could function as a backup airlock), and instrument/experiment compartment. The module also carried a Soviet version of the Manned Maneuvering Unit for the Orlan space suit, a system for regenerating water from urine, a shower, the Rodnik water storage system and six gyrodines to augment those already located in Kvant-1. Scientific equipment included a high-resolution camera, spectrometers, X-ray sensors, the Volna 2 fluid flow experiment, and the Inkubator-2 unit which was used for hatching and raising quail.[7] | ||||||

| Kristall (Technology Module) |

TM-9 | May 31, 1990 | Proton-K | Soviet Union |  |

|

| Kristall, the fourth module, consisted of two main sections. The first was largely used for materials processing (via various processing furnaces), astronomical observations and housed a biotechnology experiment utilising the Aniur electrophoresis unit. The second section was a docking compartment, which featured two APAS-89 docking ports, initially intended for use with the Buran space shuttle programme, and eventually used during the Shuttle-Mir programme. The docking compartment also contained the Priroda 5 camera, used for Earth resources experiments. Kristall also carried six gyrodines for attitude control and to augment those already on the station, and two collapsible solar arrays.[7] | ||||||

| Spektr (Power Module) |

TM-21 | June 1, 1995 | Proton-K | Russia (Builder) US (Part Financier) |

|

|

| Spektr was the first of the three modules launched as part of the Shuttle-Mir programme, and served as the living quarters for American astronauts and housed NASA-sponsored experiments. The module was designed for remote observation of Earth's environment and contained atmospheric and surface research equipment, in addition to four solar arrays which generated approximately half of the station's electrical power. The module also featured a scientific airlock to expose experiments to the vacuum of space.[8] | ||||||

| Docking Module | TM-22 | November 15, 1995 | Space Shuttle Atlantis (STS-74) |

US |  |

|

| The Docking Module was designed to help simplify Space Shuttle dockings to Mir. Before the first shuttle docking mission (STS-71), the tedious task of moving the Kristall module had to be done to ensure there was sufficient clearance between the Shuttle and Mir's solar arrays. The Docking Module provided enough clearance without the need to relocate Kristall. The module carried two identical APAS-89 docking ports. One was attached to the lateral port of Kristall and the other was open for shuttle dockings.[8] | ||||||

| Priroda (Earth Sensing Module) |

TM-23 | April 26, 1996 | Proton-K | Russia (Builder) US (Part Financier) |

|

|

| The seventh and final Mir module, Priroda's primary purpose was to conduct Earth resource experiments through remote sensing and to develop and verify remote sensing methods. The module's experiments were provided by twelve different nations, and covered microwave, visible, near infrared, and infrared spectral regions using both passive and active sounding methods. The module possessed both pressurised and unpressurised segments, and featured a large, externally mounted synthetic aperture radar dish.[8] | ||||||

International cooperation

Intercosmos

The Intercosmos ("ИнтерКосмос" Interkosmos) was a space exploration program run by the Soviet Union to allow members from military forces of allied Warsaw Pact countries to participate in manned and unmanned space exploration missions. Participation was also made available to governments of sympathetic countries, such as France and India.

Only the last three of the program's fourteen missions consisted of an expedition to Mir but none resulted in an extended stay in the station.

- Muhammed Faris from Syria aboard Soyuz TM-3.

- Aleksandr Panayatov Aleksandrov from Bulgaria aboard Soyuz TM-5.

- Abdul Ahad Mohmand from Afghanistan aboard Soyuz TM-6.

Shuttle–Mir Program

In the early 1980s, NASA planned to launch a modular space station called Freedom as a counterpart to Mir, while the Soviets were planning to construct Mir-2 in the 1990s as a replacement for the station.[8] Because of budget and design constraints, Freedom never progressed past mock-ups and minor component tests and, with the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Space Race, Freedom was nearly cancelled by the United States House of Representatives. The post-Soviet economic chaos in Russia also led to the cancellation of Mir-2, though only after its base block, DOS-8, had been constructed.[8] Similar budgetary difficulties were faced by other nations with space station projects, which prompted the American government to negotiate with European states, Russia, Japan, and Canada in the early 1990s to begin a collaborative project.[8] In June 1992, American president George H. W. Bush and Russian president Boris Yeltsin agreed to cooperate on space exploration. The resulting Agreement between the United States of America and the Russian Federation Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes called for a short, joint space program, with one American astronaut deployed to the Russian space station Mir and two Russian cosmonauts deployed to a Space Shuttle.[8]

In September 1993, American Vice-President Al Gore, Jr., and Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin announced plans for a new space station, which eventually became the International Space Station.[9] They also agreed, in preparation for this new project, that the United States would be heavily involved in the Mir program as part of an international project known as the Shuttle–Mir program.[10] The project, sometimes called "Phase One", was intended to allow the United States to learn from Russian experience with long-duration spaceflight and to foster a spirit of cooperation between the two nations and their space agencies, the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Russian Federal Space Agency (Roskosmos). The project helped to prepare the way for further cooperative space ventures; specifically, "Phase Two" of the joint project, the construction of the International Space Station (ISS). The program was announced in 1993, the first mission started in 1994 and the project continued until its scheduled completion in 1998. Eleven Space Shuttle missions, a joint Soyuz flight and almost 1000 cumulative days in space for American astronauts occurred over the course of seven long-duration expeditions.

Life on board

Inside, the 100-ton Mir looked like a cramped labyrinth, crowded with hoses, cables and scientific instruments — as well as articles of everyday life, such as photos, children's drawings, books and a guitar. It commonly housed three crew members, but it sometimes supported as many as six for up to a month. Except for two short periods, Mir was continuously occupied until August 1999.

Air aboard the station has been described as 'very healthy, - it's not dry, it's not humid. Nothing smells.' by NASA astronaut John Blaha. He also describes that with the exception of the Priroda and Spektr which were added very recently, the station does look used, which is to be expected given it has been lived in for 10 to 11 years without being brought home and cleaned.[11]

Blaha's account of the air quality aboard Mir contradicts sharply the concerns about air quality on the space station that Jerry Linenger relates in his book about his time on the facility. Linenger says that due to the age of the space station, the cooling system on board had developed a plethora of tiny leaks too small and numerous to be repaired, that permitted the constant release of coolant into the air on board making it unpleasant to breathe. He says that it was especially noticeable after he had made a space walk and become used to the clean air he had been breathing in his space suit. When he returned to the station and began breathing the air inside Mir again, he was deeply shocked by the intensity of the chemical smell and very worried about the possible negative health effects of breathing such heavily contaminated air.[12]

Linenger also relates how life on board Mir was structured and lived according to the detailed itineraries provided by ground control. Every second on board was accounted for and all activities were timetabled. After some time working on Mir Linenger came to feel that the order in which his activities were allocated did not represent the most logical or efficient order possible for these activities. He decided to perform his tasks in an order that he felt enabled him to work more efficiently, be less fatigued, and suffer less from stress. Linenger noted that his comrades on Mir did not "improvise" in this way, and as a medical doctor he observed the effects of stress on his comrades that he believed was the outcome of following an itinerary without making modifications to it. Linenger noted that despite this, his comrades performed all their tasks in a supremely professional manner.[12]

During the Shuttle–Mir programme, Russian cosmonauts were tasked with station upkeep and maintenance while the American astronauts conducted scientific experiment operations in the areas of human physiology, life science, microbiology, and materials science.[11]

Astronaut Shannon Lucid, who set the record for longest stay in space by a woman while aboard Mir (surpassed by Sunita Williams 11 years later on the ISS), also commented about working aboard Mir saying "I think going to work on a daily basis on Mir is very similar to going to work on a daily basis on an outstation in Antarctica. The big difference with going to work here is the isolation, because you really are isolated. You don't have a lot of support from the ground. You really are on your own."[11]

Two amateur radio call signs, U1MIR and U2MIR, were assigned to Mir in the late 1980s, allowing amateur radio operators on Earth to communicate with the cosmonauts.[13]

Peter Rodney Llewellyn almost visited Mir in 1999 after promising US$100 million for the privilege.[14][15]

Station operations

Expeditions

Early existence

Due to the pressure to launch the station in such short order, mission planners were left without Soyuz spacecraft or modules to launch to the station at first. It was decided to launch Soyuz T-15 on a dual mission to both Mir and Salyut 7.[6]

Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov first docked with the Mir space station on March 15, 1986. During their nearly 51-day stay on Mir, they brought the station online and checked its systems. They also unloaded two Progress spacecraft launched after their arrival, Progress-25 and Progress-26.[16]

On May 5, 1986 they undocked from Mir for a day-long journey to Salyut 7. They spent 51 days there and gathered 400 kg of scientific material from Salyut 7 for return to Mir. While Soyuz T-15 was at Salyut 7, the unmanned Soyuz TM-1 arrived at the unoccupied Mir and remained for 9 days, testing the new Soyuz TM. Soyuz T-15 redocked with Mir on June 26 and delivered the experiments and 20 instruments, including a multichannel spectrometer. The EO-1 crew spent their last 20 days on Mir conducting Earth observations before returning to earth on July 16, 1986, leaving the new station unoccupied.[17]

The second expedition to Mir, Mir EO-2, launched on Soyuz TM-2 on February 5, 1987. During their stay, the Kvant-1 module was launched on March 30, 1987. It was the first, experimental version of a planned series of '37K' modules scheduled to be launched to Mir on the Soviet Buran space shuttle. Kvant-1 was originally planned to dock with Salyut 7; however, due to technical problems during its development, it was reassigned for Mir. The module carried the first set of six gyroscopes for attitude control. The module also carried instruments for X-ray and ultraviolet astrophysical observation.[7]

The initial rendezvous of the Kvant-1 module with Mir on April 5, 1987 was troubled by the failure of the onboard control system. After the failure of the second attempt to dock, the onboard cosmonauts, Yuri Romanenko and Aleksandr Laveykin, conducted a spacewalk to fix the problem. They found a trash bag between the module and the station, which prevented the docking. The bag was left in orbit after the departure of one of the cargo ships. They removed the bag and completed docking on April 12.[18][19]

The Soyuz TM-2 launch was the beginning of a string of 6 Soyuz launches and three long-duration crews between February 5, 1987 and April 27, 1989. This time period also saw the first international visitors to the station, Muhammed Faris, Abdul Ahad Mohmand and Jean-Loup Chrétien. With the departure of Mir EO-4 on Soyuz TM-7 April 27, 1989 the station was once again left unoccupied.

Second start

The launch of Soyuz TM-8 on September 5, 1989 marked the beginning of the longest human presence in space to date. It also marked the beginning of Mir's second expansion. The Kvant-2 and Kristall modules were now ready for launch. Alexander Viktorenko and Aleksandr Serebrov docked with Mir and brought the station out of its five-month hibernation. On September 29 the cosmonauts installed equipment in the docking system in preparation for the arrival of Kvant 2, the first of the 20-ton add-on modules based on the TKS spacecraft from the Almaz program [20]

After a delay of 40 days due to problems with a batch of computer chips, Kvant-2 was launched on November 26. After problems deploying the craft's solar array and with the automated docking systems on both Kvant-2 and Mir, Kvant-2 was docked manually on December 6. Kvant-2 added a second set of gyrodines to Mir. The module also carried the new life support systems for recycling water and generating oxygen on board Mir, reducing its dependence on resupply from the ground. Kvant-2 also featured a large airlock with a one-meter hatch. A special backpack unit, an equivalent of the U.S. Manned Maneuvering Unit, was located inside Kvant-2's airlock.[20][21]

Soyuz TM-9 launched Mir EO-6 crew members Anatoly Solovyev and Aleksandr Balandin on February 11, 1990. While docking, the EO-5 crew on board Mir saw that 3 thermal blankets on the Soyuz-TM 9 were loose, potentially creating problems on reentry. It was decided that this would be manageable. Their stay on board Mir saw the addition of the Kristall module. The module was launched on May 31. The first docking attempt on June 6 was aborted due to an attitude control thruster failure. The Kristall module arrived at Mir’s front port on June 10, and was relocated to the lateral port opposite Kvant-2 the next day, restoring the equilibrium of the complex. Due to the delay in the docking of Kristall, EO-6 was extended by 10 days to permit the activation of Kristall’s systems, and to accommodate the EVA to repair the loose thermal blankets on Soyuz-TM 9.[22]

The Kristall module contained a number of furnaces for the creation of crystals in micro-gravity. Also on board was biotechnology research equipment, including a small greenhouse for plant cultivation experiments. The unit was equipped with a source of light and a feeding system. The module also contained equipment for astronomy observations. The main feature, however, was the two APAS-89 Androgynous Peripheral Attach System docking ports designed to be compatible with the Buran shuttle. Although they were never used with a Buran Shuttle, they were later used with the American Space Shuttle.[23]

The EO-7 relief crew arrived aboard Soyuz TM-10 on August 3, 1990. The new crew arrived at Mir with quail for Kvant-2's cages. A quail laid an egg en route to the station. It was returned to Earth, along with 130 kg of experiment results and industrial products, in Soyuz TM-9.[22] Three more expeditions continued to visit Mir while tensions back on Earth grew. The Mir EO-10 crew launched aboard Soyuz TM-13 on October 2, 1991 was the last crew to launch from the USSR, and continued the occupation of Mir through the fall of the Soviet Union. The unlaunched modules, Spektr and Priroda, were not so lucky. The newly formed Russian Federal Space Agency was unable to finance them and they were put into storage, ending Mir's second expansion.[24][25][26]

Shuttle–Mir

The US involvement in Mir brought new funds to the station. The most notable use of these was the completion and launch of the Spektr & Priroda modules and the construction of a docking module to make the process of docking the shuttle to the station easier.[8]

In 1997 the crew of Mir, Linenger and the Russians Vasili Tsibliyev & Aleksandr Lazutkin faced several problems:

- The most severe fire ever aboard an orbiting spacecraft which was caused by a backup oxygen-generating device.

- Failures of various on board systems.

- Near collision with a Progress resupply cargo ship during a long-distance manual docking system test.

- Total loss of station electrical power and, as a result, attitude control, resulting in a slow, uncontrolled "tumble" through space.

Linenger was succeeded by Anglo-American astronaut Michael Foale, carried up by Atlantis on STS-84, alongside Russian mission specialist Elena Kondakova.

Foale's increment proceeded fairly normally until June 25, when during the second test of the Progress manual docking system, TORU, the resupply ship collided with solar arrays on the Spektr module and crashed into the module's outer shell, holing the module and causing a depressurisation of the station, the first ever on-orbit depressurisation in the history of spaceflight. Only quick actions on the part of the crew, cutting cables leading to the module and closing Spektr's hatch, prevented the crew abandoning the station in their Soyuz lifeboat. Their efforts stabilised the station's air pressure, whilst the pressure in Spektr, containing many of Foale's experiments and personal effects, dropped to a vacuum. Fortunately, food, water and other vital supplies were stored in other modules, and remarkable salvage and replanning effort by Foale and the science community maximized the scientific return.[27][28]

In an effort to restore some of the power and systems lost following the isolation of Spektr and to attempt to locate the leak, Mir's new commander Anatoly Solovyev and flight engineer Pavel Vinogradov carried out a risky salvage operation later in the mission, entering the empty module during a so-called "IVA" spacewalk, inspecting the condition of hardware and running cables through a special hatch from Spektr's systems to the rest of the station. Following these first investigations, Foale and Solovyev conducted a 6-hour EVA on the surface of Spektr to inspect the damage to the punctured module.[27][30]

Final days and deorbit

Near the end of its life, there were plans for private interests to purchase Mir, possibly for use as the first orbital television/movie studio. The privately-funded Soyuz TM-30 mission by MirCorp, launched on April 4, 2000, carried two crew members, Sergei Zalyotin and Alexandr Kaleri, to the station for two months to do repair work with the hope of proving that the station could be made safe. But this was to be the last manned mission to Mir. While Russia was optimistic about Mir's future, its commitments to the International Space Station project left no funding to support the aging Mir.[31]

Mir's deorbit was done in three stages. The first stage was waiting for atmospheric drag to decay Mir’s orbit an average of 220 kilometers (137 mi). This began with the docking of Progress M1-5, a modified version of the Progress M carrying 2.5 times more fuel in place of supplies. The second stage was the transfer of the station into a 165 × 220 km (103 × 137 mi) orbit. This was achieved with two burns of the Progress M1-5's control engines at 00:32 UTC and 02:01 UTC on March 23, 2001. After a two-orbit pause, the third and final stage of Mir's deorbit began with the burn of Progress M1-5's control engines and main engine at 05:08 UTC, lasting a little over 22 minutes. Reentry into Earth's atmosphere (100 km/60 mi) of the 15-year-old space station occurred at 05:44 UTC near Nadi, Fiji. Major destruction of the station began around 05:52 UTC and the unburned fragments fell into the South Pacific Ocean around 06:00 UTC.[32][33]

Visiting spacecraft

Mir was primarily supported by the Russian Soyuz and Progress spacecraft. Soyuz craft provided manned access to and from the station, allowing for crew rotations, and also functioned as a lifeboat for the station, allowing for a relatively quick return to earth in the event of an emergency.[34] The unmanned Progress cargo vehicles were only used to resupply the station and were incapable of surviving reentry.[35]

It was anticipated that it would also be the destination for flights by the later-abandoned Buran space shuttle. The Kristall module even carried two APAS-89 Androgynous Peripheral Attach System docking ports designed to be compatible with the Buran shuttle. These were later used with the American Space Shuttle.[23]

During the Shuttle-Mir Program, Mir was also supported by Space Shuttles, allowing American and other western astronauts to visit or stay long-term on the station. The visiting US shuttles used a modified docking collar originally designed for the Soviet Buran shuttle, mounted on a bracket intended for use with Space Station Freedom but this required the relocation of the Kristall module to ensure sufficient distance between the shuttle and Mir's solar arrays.[8] In order to eliminate the need to move the module and retract solar arrays for clearance issues, a Docking Module was later added to the end of Kristall.[36] The shuttles provided crew rotation of the American astronauts on station as well as carrying cargo to and from the station, performing some of the largest transfers of cargo of the time. With a space shuttle docked to Mir the temporary enlargements of living and working areas amounted to a complex that was the largest spacecraft in history at that time, with a combined mass of 250 tonnes (280 short tons).[8]

Mission control centre

References

- ↑ "Mir-Orbit Data". Heavens-Above.com. 23 March 2001. http://www.heavens-above.com/orbit.aspx?lat=48.213&lng=16.296&alt=302&loc=Kuffner-Sternwarte&TZ=CET&satid=16609. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ↑ "Mir FAQ - Facts and history". European Space Agency. 21 February 2001. http://www.esa.int/esaCP/ESA28WTM5JC_Life_2.html. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ "Mir Space Station - Mission Status Center". Spaceflight Now. 23 March 2001. http://spaceflightnow.com/mir/status.html. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ "NASA - NSSDC - Spacecraft - Details - Mir". NASA. 23 July 2010. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/masterCatalog.do?sc=1986-017A. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ "Soviet/Russian space programmes Q&A". NASASpaceflight.com. http://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?topic=5966.465. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Wade, Mark. "Mir complex". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/mirmplex.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 David S. F. Portree (March 1995). Mir Hardware Heritage. NASA. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Mir_Hardware_Heritage.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 David Harland (30 November 2004). The Story of Space Station Mir. New York: Springer-Verlag New York Inc. ISBN 978-0-387-23011-5. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=sBdUh8WqEfYC&dq=the+story+of+space+station+mir&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ↑ Donna Heivilin (21 June 1994). "Space Station: Impact of the Expanded Russian Role on Funding and Research" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. http://archive.gao.gov/t2pbat3/151975.pdf. Retrieved 3 November 2006.

- ↑ Kim Dismukes (4 April 2004). "Shuttle–Mir History/Background/How "Phase 1" Started". NASA. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/history/shuttle-mir/history/h-b-start.htm. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 From Mir to Mars PBS: From Mir to Mars, Accessed September 14, 2008

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Linenger, Jerry (January 1, 2001). Off the Planet: Surviving Five Perilous Months Aboard the Space Station Mir. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071372305. http://www.amazon.co.uk/Off-Planet-Surviving-Perilous-Station/dp/007137230X/ref=sr_1_1/202-3649698-1866219?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1174383967&sr=8-1.

- ↑ Astronaut Hams Astronaut Hams

- ↑ No Mir flight for British businessman BBC News: May 27, 1999

- ↑ Sprenger, Polly (1999-05-26). "UK Businessman Booted Off Mir". Wired. http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/1999/05/19895. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- ↑ Anikeev, Alexander. "Spacecraft "Soyuz-T15"". Manned Astronautics. http://space.kursknet.ru/cosmos/english/machines/st15.sht. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Mir EO-1". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/mireo1.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Mir EO-2". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/mireo2.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ Zak, Anatoly. "Spacecraft: Manned: Mir: Kvant-1 Module". RussianSpaceweb.com. http://www.russianspaceweb.com/mir_kvant.html. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Wade, Mark. "Mir EO-5". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/mireo5.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ↑ Zak, Anatoly. "Spacecraft: Manned: Mir: Kvant-2 Module". RussianSpaceWeb.com. http://www.russianspaceweb.com/mir_kvant-2.html. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Wade, Mark. "Mir EO-6". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/mireo6.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Zak, Anatoly. "Spacecraft: Manned: Mir: Kristall Module". RussianSpaceWeb.com. http://www.russianspaceweb.com/mir_kristall.html. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Mir EO-10". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/mireo10.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Spektr". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/spektr.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Priroda". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/priroda.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "Shuttle-Mir History/Shuttle Flights and Mir Increments". NASA. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/history/shuttle-mir/history/h-flights.htm. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Burrough, Bryan (January 7, 1998). Dragonfly: NASA and the Crisis Aboard Mir. London, UK: Fourth Estate Ltd.. ISBN 1-84115-087-8. http://www.amazon.co.uk/Dragonfly-NASA-Crisis-Aboard-Mir/dp/1841150878/ref=sr_1_2/202-3649698-1866219?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1173807659&sr=8-2.

- ↑ van den Berg, Chris (August 8, 1997). "Mir News 376: Soyuz-TM26". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/details/mir50763.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- ↑ Hoffman, David (August 22, 1997). "Crucial Mir spacewalk carries high hopes - continued Western support could hinge on mission's success". Washington Post (Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank): pp. a1.

- ↑ "Mir Destroyed in Fiery Descent". CNN. March 22, 2001. http://archives.cnn.com/2001/TECH/space/03/23/mir.descent/index.html. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ "The Final Days of Mir". The Aerospace Corporation. http://www.reentrynews.com/Mir/sequence.html. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ "Mir Space Station Reentry Page". Space Online. http://www.ik1sld.org/mirreentry_page.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ Kim Dismukes (4 March 2004). "Shuttle–Mir History/Spacecraft/Mir Space Station/Soyuz". NASA. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/history/shuttle-mir/spacecraft/s-mir-soyuz.htm. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ Kim Dismukes (4 March 2004). "Shuttle–Mir History/Spacecraft/Mir Space Station/Progress Detailed Description". NASA. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/history/shuttle-mir/spacecraft/s-mir-detailed-main.htm. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Mir Docking Module". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/mirodule.htm. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- NASA-4 Jerry Linenger:Fire and Controversy

- Mir has 3-man 'lifeboat' ready - June 25, 1997 CNN

- Mir Suffering After Collision International Events - Apr 18, 1997

- Russian Mir Space Station Suffers Near-Catastrophe

- Mir Hardware Heritage - NASA report (PDF format)

- Mir Mission Chronicle - NASA report (PDF format)

- Mir-Shuttle:Phase 1 Program Joint Report (PDF format)

- Soviet Space Stations as Analogs - NASA report (PDF format)

External links

- NASA animation of Mir's deorbit.

- Mir Diary

- Site contains detailed diagrams, pictures and background info

- Site describes the Mir-Shuttle Docking Module

- Site contains information on problems aboard Mir

- Screensaver realistically shows Mir construction

- Site describes MirCorp and the privatization of the Mir

- Mir diagram from Encyclopedia Britannica

| Preceded by Salyut 7 |

Mir 1986–2001 |

Succeeded by Mir-2 as the ROS in the ISS |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||