Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò Paganini (27 October 1782 – 27 May 1840) was an Italian violinist, violist, guitarist, and composer. He was one of the most celebrated violin virtuosi of his time, and left his mark as one of the pillars of modern violin technique. His Caprice No. 24 in A minor, Op. 1, is among the best known of his compositions, and has served as an inspiration for many prominent composers.

Contents |

Biography

Childhood

Niccolò Paganini was born in Genoa, Italy, the third of the six children of Antonio and Teresa (née Bocciardo) Paganini. Paganini's father was an unsuccessful trader, but he managed to supplement his income through playing music on the mandolin. At the age of five, Paganini started learning the mandolin from his father, and moved to the violin by the age of seven. His musical talents were quickly recognized, earning him numerous scholarships for violin lessons. The young Paganini studied under various local violinists, including Giovanni Servetto and Giacomo Costa, but his progress quickly outpaced their abilities. Paganini and his father then traveled to Parma to seek further guidance from Alessandro Rolla. But upon listening to Paganini's playing, Rolla immediately referred him to his own teacher, Ferdinando Paër and, later, Paër's own teacher, Gasparo Ghiretti. Though Paganini did not stay long with Paër or Ghiretti, the two had considerable influence on his composition style.

Early career

The French invaded northern Italy in March 1796, and Genoa was not spared. The Paganinis sought refuge in their country property in Ramairone. By 1800, Paganini and his father traveled to Livorno, where Paganini played in concerts and his father resumed his maritime work. In 1801, Paganini, aged 18 at the time, was appointed first violin of the Republic of Lucca, but a substantial portion of his income came from freelancing. His fame as a violinist was matched only by his reputation as a gambler and womanizer.

In 1805, Lucca was annexed by Napoleonic France, and the region was ceded to Napoleon's sister, Elisa Baciocchi. Paganini became a violinist for the Baciocchi court, while giving private lessons for her husband, Felice. In 1807, Baciocchi became the Grand Duchess of Tuscany and her court was transferred to Florence. Paganini was part of the entourage, but, towards the end of 1809, he left Baciocchi to resume his freelance career.

Travelling virtuoso

For the next few years, Paganini returned to touring in the areas surrounding Parma and Genoa. Though he was very popular with the local audience, he was still not very well known in Europe. His first break came from an 1813 concert which took place at La Scala in Milan. The concert was a great success, and as a result Paganini began to attract the attention of other prominent, albeit more conservative, musicians across Europe. His early encounters with Charles Philippe Lafont and Ludwig Spohr created intense rivalry. His concert activities, however, were still limited to Italy for the next few years.

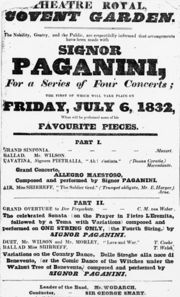

His fame spread across Europe with a concert tour that started in Vienna in August, 1828, stopping in every major European city in Germany, Poland, and Bohemia until February, 1831 in Strasburg. This was followed by tours in Paris and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. His technical ability and his willingness to display it received much critical acclaim. In addition to his own compositions, theme and variations being the most popular, Paganini also performed modified versions of works (primarily concertos) written by his early contemporaries, such as Rodolphe Kreutzer and Giovanni Battista Viotti. Ignoring the many private parties he played at, the following list gives an indication of his popularity and his schedule:[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

-

- July 1829, left Warsaw

- Nov 1829, Munich, 3 concerts

- End of 1830, Farewell concert in Frankfurt

- Arrived in Strasbourg, gave 2 concerts

- End Feb onwards 1831, he gave 12 concerts in Paris

- Early in May 1831, left Paris for London; gave several concerts in Northern France on the way

- Announced a concert in Kings Theatre in London for 21 May 1831, but was postponed until 3 June

- 2nd concert played on 10 June, same venue. 13 June, 3rd concert, same venue. 16 June, 4th concert, same venue. 22 June, 5th (final) concert, same venue

- Final concerts were announced - one was played on 4 July 1831

- Gave two concerts at the London Tavern in July

- Two concerts at Cheltenham in July

- 9 July, Concert at Lord Mayor's banquet in Mansion House

- August - concerts in London

- August - 3 concerts in Norwich

- End of August - set out for Dublin

- Was in Dublin for the music festival (30 Aug - 3 Sept 1831) He gave 3 concerts. There is some descrepencies here, since some references state the music festival was in 1830.

- Gave 3 evening concerts in the Theatre Royal

- Returned to London

- October 1831 mentions he played in Edinburgh in 1831, also mentions a private party he played in Edinburgh.

- Dec 1831 - Concert announce in Bristol

- Early 1832 - Concert in Leeds

- Feb 1832 - Concert in Birmingham

- Early 1832, concert in Brighton

- March 1832 - Left London for Paris

Late career and health decline

Throughout his life, Paganini was no stranger to chronic illnesses. His frequent concert schedule, as well as his extravagant lifestyle, eventually took their toll on his health. He was diagnosed with syphilis as early as 1822, and his remedy, which included mercury and opium, resulted in serious health and psychological problems. In 1834, while still in Paris, he was treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. Though his recovery was reasonably quick, his future career was marred with frequent cancellations due to various health problems, from the common cold to depression, which lasted from days to months.

In September 1834, Paganini put an end to his concert career and returned to Genoa. Contrary to popular beliefs (involving him wishing to keep his music and techniques secret), Paganini devoted his time to the publication of his compositions and violin methods. He accepted students, of whom two enjoyed moderate success: violinist Camillo Sivori and cellist Gaetano Ciandelli. Neither considered Paganini helpful or inspirational, however. In 1835, Paganini returned to Parma, this time under the employ of Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria, Napoleon's second wife. He was in charge of reorganizing her court orchestra. Unfortunately, he eventually became at odds with the players and court, so his visions never saw the light of day.

Final years, death and burial

In 1836, Paganini returned to Paris to set up a casino. Its immediate failure left him in financial ruins, and he auctioned off his personal effects, including his musical instruments, to recoup his losses. On Christmas of 1838, he left Paris for Marseilles and, after a brief stay, traveled to Nice where he fell ill once more. Paganini, wrongly assuming it to be a premature gesture, refused the Last Rites to be performed on him by a priest from the local parish. However, on 27 May 1840, Paganini died from internal hemorrhaging before a priest could be summoned.

It was on these grounds, and his widely rumored association with the devil, that his body was denied a Catholic burial in Genoa. It took four years, and an appeal to the Pope, before the body was allowed to be transported to Genoa, but was still not buried. His remains were finally put to rest in 1876 in a cemetery in Parma. In 1893, the Czech violinist, František Ondříček, persuaded Paganini's grandson, Attila, to allow a viewing of the violinist's body. After the bizarre episode, Paganini's body was finally reinterred in a new cemetery in Parma in 1896.

Personal and professional relationships

Though having no shortage of romantic conquests, Paganini was once seriously involved with a singer named Antonia Bianchi from Como, whom he met in Milan in 1813. The two concertized together throughout Italy. They had a son, Achilles Cyrus Alexander, born on 23 July 1825, in Palermo and baptized at San Bartolomeo's. Their union was never legalized and it ended around April 1828 in Vienna. Paganini brought Achilles on his European tours, and Achilles would later accompany his father until the latter's death. He was instrumental in dealing with his father's burial, years after his death.

Throughout his career, Paganini also became close friends with composers Gioachino Rossini and Hector Berlioz. Rossini and Paganini met in Bologna in the summer of 1818. In January 1821, on his return from Naples, Paganini met Rossini again in Rome, just in time to become the composer's substitute conductor for his opera Mathilde de Sharbran, upon the sudden death of the original conductor. The violinist's efforts earned gratitude from the composer.

Meanwhile, Paganini was introduced to Berlioz in Paris in 1833. Though Paganini also commissioned from him Harold en Italie for viola and orchestra, he never performed it, and instead it was premiered a year later by violist Christian Urhan. Despite his alleged lack of interest in Harold, Paganini often referred to Berlioz as the resurrection of Beethoven and, towards the end of his life, he gave large sums to the composer.

Paganini's instruments

Paganini was in possession of a number of fine string instruments. More legendary than these were the circumstances under which he obtained (and lost) some of them. While Paganini was still a teenager in Livorno, a wealthy businessman named Livron lent him a violin, made by the master luthier Guarneri, for a concert. Livron was so impressed with Paganini's playing that he refused to take it back. This particular violin would come to be known as Il Cannone Guarnerius.[9] On a later occasion in Parma, he won another valuable violin (also by Guarneri) after a difficult sight-reading challenge brought on by a man named Pasini.

Other instruments associated with Paganini include the Antonio Amati 1600, the Nicolò Amati 1657, the Paganini-Desaint 1680 Stradivari, the Guarneri-filius Andrea 1706, the Le Brun 1712 Stradivari, the Vuillaume c.1720 Bergonzi, the Hubay 1726 Stradivari, and the Comte Cozio di Salabue 1727 violins; the Countess of Flanders 1582 da Salò-di Bertolotti, and the Mendelssohn 1731 Stradivari violas; the Piatti 1700 Goffriller, the Stanlein 1707 Stradivari, and the Ladenburg 1736 Stradivari cellos; and the Grobert of Mirecourt 1820 (guitar).[10][11]

Compositions

Paganini composed his own works to play exclusively in his concerts, all of which had profound influences on the evolution of violin techniques. His 24 Caprices were probably composed in the period between 1805 to 1809, while he was in the service of the Baciocchi court. Also during this period, he composed the majority of the solo pieces, duo-sonatas,trios and quartets for the guitar. These chamber works may have been inspired by the publication, in Lucca, of the guitar quintets of Boccherini. Many of his variations (and he has become the de facto master of this musical genre), including Le Streghe, The Carnival of Venice, and Nel cor più non mi sento, were composed, or at least first performed, before his European concert tour.

Generally speaking, Paganini's compositions were technically imaginative, and the timbre of the instrument was greatly expanded as a result of these works. Sounds of different musical instruments and animals were often imitated. One such composition was titled Il Fandango Spanolo (The Spanish Dance), which featured a series of humorous imitations of farm animals. Even more outrageous was a solo piece Duetto Amoroso, in which the sighs and groans of lovers were intimately depicted on the violin. Fortunately there survives a manuscript of the Duetto which has been recorded, while the existence of the Fandango is known only through concert posters.

However, his works were criticized for lacking characteristics of true polyphonism, as pointed out by Eugène Ysaÿe.[12] Yehudi Menuhin, on the other hand, suggested that this might have been the result of his reliance on the guitar (in lieu of the piano) as an aid in composition.[9] The orchestral parts for his concertos were often polite, unadventurous, and clearly supportive of the soloist. In this, his style is consistent with that of other Italian composers such as Paisiello, Rossini and Donizetti, who were influenced by the guitar-song milieu of Naples during this period.[13]

Paganini was also the inspiration of many prominent composers. Both "La Campanella" and the A minor caprice (Nr. 24) have been an object of interest for a number of composers. Franz Liszt, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Boris Blacher, Andrew Lloyd Webber, George Rochberg and Witold Lutosławski, among others, wrote well-known variations on these themes.

Paganini and the evolution of violin technique

The Israeli violinist Ivry Gitlis once referred to Paganini as a phenomenon rather than a development. Though some of the techniques frequently employed by Paganini were already present, most accomplished violinists of the time focused on intonation and bowing techniques, the so-called right-hand techniques for string players. Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) was considered a pioneer in transforming the violin from an ensemble instrument to a solo instrument. In the meantime, the polyphonic capability of the violin was firmly established through the Sonatas and Partitas BWV 1001-1006 of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Other notable violinists included Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) and Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770), who, in their compositions, reflected the increasing technical and musical demands on the violinist. Although the role of the violin in music drastically changed through this period, progress in violin technique was steady but slow. Techniques requiring agility of the fingers and the bow were still considered unorthodox and discouraged by the established community of violinists.

Much of Paganini's playing (and his violin composition) was influenced by two violinists, Pietro Locatelli (1693-1746) and August Duranowski (1770-1834). During Paganini's study in Parma, he came across the 24 Caprices of Locatelli (entitled L'arte di nuova modulazione - Capricci enigmatici or The art of the new style - the enigmatic caprices). Published in the 1730s, they were shunned by the musical authorities for their technical innovations, and were forgotten by the musical community at large. Around the same time, Durand, a former student of Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824), became a celebrated violinist. He was renowned for his use of harmonics and the left hand pizzicato in his performance. Paganini was impressed by Durand's innovations and showmanship, which later also became the hallmarks of the young violin virtuoso. Paganini was instrumental in the revival and popularization of these violinistic techniques, which are now incorporated into regular compositions.

Another aspect of Paganini's violin techniques concerned his flexibility. He had exceptionally long fingers and was capable of playing three octaves across four strings in a hand span, a feat that is still considered impossible by today's standards. His seemingly unnatural ability may have been a result of Marfan syndrome.[14]

Works inspired by Paganini

The Caprice No. 24 in A minor, Op.1 (Tema con variazioni) has been the basis of works by many other composers. For a separate list of these, see Caprice No. 24 (Paganini).

Other works inspired by Paganini include:

- James Barnes – Fantasy Variations on a Theme by Nicolo Paganini

- Mike Campese - "Paganini", arrangement of Caprice No. 16 and various works.

- Alfredo Casella - Paganiniana, arrangement of four caprices

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco − Capriccio Diabolico for classical guitar is a homage to Paganini, and quotes "La campanella"

- Frédéric Chopin − Souvenir de Paganini for solo piano (1829; published posthumously)

- Luigi Dallapiccola – Sonatina canonica in mi bemolle maggiore su "Capricci" di Niccolo Paganini, for piano (1946)

- Johann Nepomuk Hummel - Fantasia for piano in C major "Souvenir de Paganini", WoO 8, S. 190.

- Fritz Kreisler − Paganini Concerto in D major (recomposed paraphrase of the first movement of the Op. 6 Concerto) for violin and orchestra

- Franz Lehár − Paganini, a fictionalized operetta about Paganini (1925)

- Franz Liszt − Six Grandes Études de Paganini, S.141 for solo piano (1851) (virtuoso arrangements of 5 caprices, including the 24th, and La Campanella from Violin Concerto No. 2)

- Nathan Milstein − Paganiniana, an arrangement of Caprice No. 24, with variations based on the other caprices

- Sergei Rachmaninoff - Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, one of Rachmaninoff's most famous works, is based on Caprice No. 24.

- George Rochberg − Caprice Variations (1970), 50 variations for solo violin

- Uli Jon Roth − "Scherzo Alla Paganini" and "Paganini Paraphrase"

- Robert Schumann − Studies after Caprices by Paganini, Op. 3 (1832; piano); 6 Concert Studies on Caprices by Paganini, Op. 10 (1833, piano). A movement from his piano work Carnaval (Op. 9) is named for Paganini.

- Marilyn Shrude − Renewing the Myth for alto saxophone and piano

- Steve Vai − "Eugene's Trick Bag" from the movie Crossroads. Based on Caprice Nr. 5

- Philip Wilby - Paganini Variations, for both wind band and brass band

- Eugène Ysaÿe − Paganini variations for violin and piano

Memorials

The Paganini Competition (Premio Paganini) is an international violin competition created in 1954 in his home city of Genoa and named in his honour.

In 1972 the State of Italy purchased a large collection of Niccolò Paganini manuscripts from the W. Heyer Library of Cologne. They are housed at the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome.[15]

In 1982 the city of Genoa commissioned a thematic catalogue of music by Paganini, edited by Maria Rosa Moretti and Anna Sorrento, hence the abbreviation "MS" assigned to his catalogued works.[16]

A minor planet 2859 Paganini discovered in 1978 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh is named after him.[17]

Dramatic portrayals

Paganini has been portrayed by a number of actors in film and television productions, including Stewart Granger in the 1946 biographical portrait The Magic Bow, Roxy Roth in A Song to Remember, and Klaus Kinski in Kinski Paganini (1989).[18]

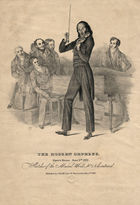

In the Soviet 1982 miniseries Niccolo Paganini the musician is portrayed by the Armenian stage master Vladimir Msryan. The series focuses on Paganini's persecution by the Roman Catholic Church. Another Soviet cinematic legend, Armen Dzhigarkhanyan plays Paganini's fictionalized arch-rival, an insidious Jesuit official. The information in the series was generally accurate, however it also played to some of the myths and legends rampant during the musician's lifetime. In particular, a memorable scene shows Paganini's adversaries sabotaging his violin before a high-profile performance, causing all strings but one to break during the concert. An undeterred Paganini continues to perform on three, two, and finally on a single string.

In Don Nigro's satirical comedy Paganini (1995), the great violinist seeks vainly for his salvation, claiming that he unknowingly sold his soul to the Devil. "Variation upon variation," he cries at one point, "but which variation leads to salvation and which to damnation? Music is a question for which there is no answer."

Paganini is portrayed as having killed three of his lovers and sinking repeatedly into poverty, prison, and drink. Each time he is "rescued" by the Devil who appears in different guises, returning Paganini's violin so he can continue playing. In the end, Paganini's salvation -- administered by a god-like Clockmaker -- turns out to be imprisonment in a large bottle where he plays his music for the amusement of the public through all eternity.

"Do not pity him, my dear," the Clockmaker tells Antonia, one of Paganini's murdered wives. "He is alone with the answer for which there is no question. The saved and the damned are the same."

Paganini in popular culture

Paganini made an appearance in Hugh Lofting's children's novel Doctor Dolittle's Caravan. In this novel, Doctor Dolittle forms an opera company made up entirely of birds, instead of human performers. Paganini attends a performance of the bird opera, causing quite a stir amongst the crowd, and then meets with Doctor Dolittle after the performance to discuss it.

Paganini is a major character in Madame Blavatsky's The Ensouled Violin, a short story included in the collection Nightmare Tales. The story recounts rumors that (a) the strings of Paganini's violin were made from human intestines and (b) Paganini murdered both his wife and mistress and imprisoned their souls in his violin.

In the film The Hunt for Red October, the character "Jonesey", SONAR operator on the USS Dallas, is a fan of Paganini and somehow plays a piece of the composers music over the submarine's SONAR system. This results in other submarines, including one "way out at Pearl" picking up the music over their SONAR equipment, causing a minor fracas. In the film Paganini is confused with Pavarotti, much to Jonesey's consternation.

The animated superhero series The Tick featured a supervillain known as "Octo Paganini" (who had six arms and could play three violins simultaneously) in the episode The Tick Vs. Europe.[19]

In Andrew Clements' young adult novel, Things Hoped For, Paganini serves as inspiration for the main character, Gwendolyn, an aspiring young violinist.

In the Sherlock Holmes mystery "The Adventure of the Cardboard Box", Sherlock Holmes discusses Paganini with Watson while drinking wine.

In the Showtime television series Queer As Folk, the main character Brian Kinney often condescendingly refers to his lover's, Justin Taylor, one time boyfriend Ethan Gold, who is an aspiring violinist as Paganini Jr.

In the 1986 film Crossroads, the hero wins a guitar duel by playing Paganini's Caprice #5 with perfect skill on an electric guitar. It has been speculated that his opponent (called "Jack Butler" in the film and portrayed by Steve Vai) is meant to recall Paganini himself, since he is gaunt, has unkempt hair and rolls his eyes while playing in the same fashion as Paganini. The film's plot centers on a blues man who sold his soul to Satan, which Paganini was said to have done to acquire his extraordinary talent.

Media

See also

- Paganini Competition

- Paganiniana

References

- ↑ Nicolo Paganini: His Life and Work

- ↑ The Dublin University magazine: a literary and political journal, Volume 37

- ↑ Crescendo of the virtuoso: spectacle, skill, and self-promotion in Paris

- ↑ Article on Paganini in Museum of foreign literature, science and art, Volume 19 (up to 1928)

- ↑ The Edinburgh literary journal Dec 1830

- ↑ Memoirs of Mrs. Hemans

- ↑ Old Billboard Ad

- ↑ Tait's Edinburgh magazine

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Yehudi Menuhin and Curtis W. Davis. The Music of Man. Methuen, 1979.

- ↑ Mediatheque.cite

- ↑ Hautetfort.com

- ↑ Lev Solomonovich Ginzburg. Ysaye. Paganiniana, 1980.

- ↑ N. Till: Rossini, p. 50-51. Omnibus Press, 1987

- ↑ From Paganini stories myths. The AFU and Urban Legends Archive. Retrieved on January 13, 2009; based primarily on Schoenfeld MR (January 1978). "Nicolo Paganini. Musical magician and Marfan mutant?". JAMA 239 (1): 40–2. doi:10.1001/jama.239.1.40. PMID 336919. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/239/1/40.

- ↑ Biblioteca Casanatense

- ↑ Moretti, M. R. & Sorrento, A. (eds). Catalogo tematico delle musiche di Niccolò Paganini (Genoa: Comune di Genova, 1982).

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 235. ISBN 3540002383. http://books.google.com/books?q=2859+Paganini+1978+RW1.

- ↑ IMDB. "Niccolò Paganini (Character)". IMDb.com. http://www.imdb.com/character/ch0044847/. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ↑ "The Tick Vs. Europe"

Bibliography

- Leopold Auer, Violin playing as I teach it, Stokes, 1921 (reprint Dover, 1980).

- Alberto Bachmann, An Encyclopedia of the violin, Da Capo, 1925.

- Boscassi Angelo, Il Violino di Niccolò Paganini conservato nel Palazzo Municipale di Genova, Fratelli Pagano, 1909.

- Yehudi Menuhin and William Primrose, Violin and viola, MacDonald and Jane's, 1976.

- Yehudi Menuhin and Curtis W. Davis, The Music of man, Methuen, 1979.

- John Sugden, Paganini, Omnibus Press, 1980.

- Bruno Monsaingeon,The Art of violin, NVC Arts (on film), 2001.

- Masters of the Nineteenth Century Guitar, Mel Bay Publications.

External links

- Free scores by Niccolò Paganini in the Werner Icking Music Archive (WIMA)

- Viola in music - Niccolò Paganini

- Free scores by Paganini in the International Music Score Library Project

- Closelinks.com, Free Family Tree

- Paganini's Daemon : A Most Enduring Legend, 73 minute documentary @ Google Video

- Nicolo Paganini Discography: Exhaustive list of recordings (coarse- & micro-groove records, CD, SACD, VHS & DVD) arranged under 12 instrumental sections; includes index of artists, selected album covers & detailed composition list

- Images

- Images of and about Paganini (Royal Academy of Music)

- Images of Paganini (Gallica)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||