Operation Storm

| Operation Storm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War |

|||||||||

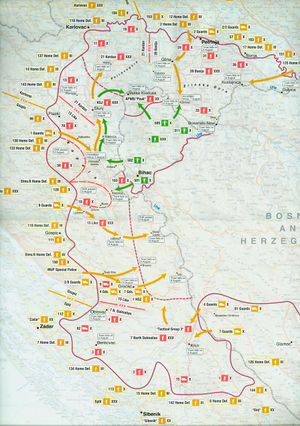

Map of Operation Storm |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

AP Western Bosnia |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Zvonimir Červenko (HV) Atif Dudakovic (ABiH) |

Mile Mrkšić (VSK) Fikret Abdić (AWB) |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 130,000 soldiers (HV),[5] ~25,000 (ABiH) 350 tanks (HV) 15 tanks (ABiH) 500 artillery pieces, 50 rocket launchers, 18 aircraft, ~17-38 helicopters, |

40,000 soldiers (VSK), ~10,000 soldiers (AWB), 400 tanks, 200 armored personnel carrier, 560 artillery pieces, 20 rocket launchers, ~320-360 air defence weapons, ~22-25 aircraft, ~13-22 helicopters, |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 174-196 soldiers killed, 1,100-1,430 wounded[6] |

(1) 500-700 soldiers and 500-677 civilians killed 2,500 wounded 5,000 POW 90,000 refugees[7] (Croatian sources) (2) 742 soldiers killed, at least 1,196 civilians killed, 200,000[6]-250,000 refugees (Serbian sources) (3)150,000-200,000 refugees (UN) |

||||||||

|

|||||

Operation Storm (Croatian, Bosnian: Operacija Oluja, Serbian: Oпeрaциja Oлуja, Operacija Oluja) is the code name given to a large-scale military operation carried out by Croatian Armed Forces, in conjunction with the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, to gain control of parts of Croatia which had been claimed by separatist ethnic Serbs, since early 1991.[8]

The operation, which took 84 hours, was documented as the largest European land offensive since World War II.[9] It began shortly before dawn on 4 August 1995 and ended with a complete victory for the Croatian forces four days later.

These forces had received instruction by a U.S.-based firm, Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI), headed by retired general Carl Vuono, which provided (along with French Foreign Legion organized training camp in Šepurine near Zadar) mainly the commissioned-officers training, but had no significant intelligence activities or professional influence on senior Croatian military strategy and tactics.[10] Its engagement was approved by the U.S. government.[11]

Former President Bill Clinton wrote in his memoirs that he believed the Serbs could only be brought to the negotiating table if they sustained major losses on the ground.[12] The negotiations produced the Dayton Peace Agreement which ended the war in the Balkans.

Former US peace negotiator Richard Holbrooke said "he realised how much the Croatian offensive in the Krajina profoundly changed the nature of the Balkan game and thus this diplomatic offensive."[13] Retired four-star General Wesley Clark, Director, Strategic Plans and Policy (J5) for the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and later Supreme Allied Commander Europe simply called it a turning point.

After the Srebrenica Massacre, there were concerns over the recurrence of the massacre in the Bihać pocket area, where the population of Bosniaks was four times larger than in Srebrenica and which was surrounded and under attack by Bosnian Serb and Croatian Serb forces.

Approximately 150,000 to 200,000[14] Serbs fled approaching Croat forces to Serb-held parts of Bosnia and Serbia. The European Union Special Envoy to the Former Yugoslavia Carl Bildt called it on 7 August 1995, "the most efficient ethnic cleansing we've seen in the Balkans."[15] The Croatian Ministry of Foreign Affairs said Bildt's assessment was "unfounded."[16] German Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkel released a statement expressing "regret" about the offensive but added, "We can't forget that the years of Serb aggression ... have sorely tried Croatia's patience."[17] The United States government called for "restraint," but said the military operation had been "provoked initially by a Krajina Serb attack on the Muslim enclave of Bihać."[17] The military operations by the army continued in Bosnia-Herzegovina under Operation Mistral.

Three Croatian generals, Ante Gotovina, Ivan Čermak and Mladen Markač, alleged to have been involved in the planning and execution of Operation Storm, were indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and are on trial in the Hague on charges of operating a joint criminal enterprise for the purpose of permanently removing the Serb population from the Krajina by force and of crimes against humanity[18]

The Croatian government maintained the operation was justified on the grounds that a sovereign state has the right to be in control of its own territory. The government also insisted that Croatian Serbs not involved in "war crimes" would be able to return to the area.[19]

In Croatia, the 5th of August is celebrated as a national holiday, Victory and Homeland Thanksgiving and the day of Croatian Defenders.

Contents |

Background

The 1990 revolt of the Croatian Serbs was centered on the predominantly Serb-populated Krajina region and eastern Croatia where Croats were in a relative majority.[20][21]

The Serbs declared their independence from Croatia by proclaiming a Republic of Serbian Krajina, which remained internationally unrecognized, and initiated an armed conflict, supported by the Yugoslav People's Army, against Croatian police and civilians. A campaign of ethnic cleansing was then started by rebel Serb forces against Croatian civilians in the areas under their control and most non-Serbs were expelled by early 1993. As of November 1993, less than 400 ethnic Croats still resided in UNPA Sector South,[22] and between 1,500 and 2,000 remained in UNPA Sector North.[23]

In January 1992, a ceasefire agreement was signed by Presidents Franjo Tuđman of Croatia and Slobodan Milošević of Serbia to suspend fighting between the two sides. During the next three years, Croatian military operations in the Krajina were mostly limited to small attacks while Serbs military operations concentrated on shelling nearby Croatian towns[24] of which the most internationally notable was the Zagreb rocket attack during May, 1995.[25][26] One notable Croatian military operation during this time was Operation Medak Pocket of September 1993, during which Croatian forces overran a small area in the mountainous region of Lika but caused an international incident in the process when Croatian forces allegedly committed war crimes against local Serb civilians.

The HV (Hrvatska vojska) played a more active role in western Bosnia, acting in concert with the Bosnian Croat HVO to combat Bosnian Serb forces. This had several advantages for the Croatians: it helped to prop up the Bosnian Croat state, it gave Croatian army commanders valuable combat experience and it put the Croatians in a good strategic position to threaten the Croatian Serbs' supply lines in Bosnia.

Timeline

Build-up to Operation Storm

After Operation Flash in May 1995 Serbian president Slobodan Milošević had made the decision to help Krajina with material, General Milan Mrkšić from Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and the people of military age who were born in the Krajina.[27] A proposed peace plan, called Z-4 plan which would give Serbs autonomy inside Croatia, which was not accepted.[28][29]

Serbs in Krajina

Although a military action was expected Milan Martić, the rebel Croatian Serb leader, and his staff refused the Z-4 plan in hopes of uniting with the Bosnian Serbs (lead by Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić) and Serbia.[30]

After Croatian victory in Operation Summer '95 during July of that year the Serbs in Krajina had logistical problems because the most important road which has connected capitals of Croatian and Bosnian Serbs had been taken. Morale had fallen to all time low and market was closed under Krajina government orders[31] They were also seriously undermined by internal political conflicts[32]

Serbs in Croatia

The Croatian Serb army, the VSK, was also significantly undermanned. Their front extended 600 km and their area of control extended 100 km to the rear, along the Bihać pocket in Bosnia. It had 55,000 soldiers to cover this front and defend the rear. 16,000 of the VSK's troops were stationed in eastern Slavonia, leaving only a theoretical maximum 39,000 to defend the main part of the RSK.

Forces opposed to Serbs

In contrast, the Croatian and Bosnian armies (the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina) had greatly strengthened their forces. They had re-equipped with more weaponry from former republics of the USSR — despite the arms embargoes that were in force, which Croatia saw as a political manoeuvre of pro-Serbian political forces to keep Croatia unarmed against hyper-armed Serbs and the JNA. They also had strategic advantages, with much shorter lines of communication than their enemies. These advantages were demonstrated in Western Slavonia in May 1995, when the Croatian Army rapidly overran a Serb-held area in Operation Flash. Serb forces retaliated by attacking the capital Zagreb with Orkan missiles from the Krajina; killing 7 and wounding over 175 civilians.

Operations in July-August 1995

In July 1995, the Croatian and Bosnian armies jointly captured the crucial western Bosnian towns of Glamoč, and Bosansko Grahovo, along with Livno's western villages. This cut vital Croatian Serb supply lines and effectively meant that the Croatian Serb capital of Knin was surrounded on three sides. The rebel Croatian Serbs joined the Bosnian Serbs (aided by Fikret Abdić's Bosniak rebels) in an offensive aimed at eliminating the Bihać pocket which had been surrounded since 1992 and held over 40,000 Bosnian refugees. The international community feared a repeat of a Srebrenica Genocide there.

During the last week of July and the first few days of August 1995, the Croatian Army undertook a massive military build-up along the front lines in the Krajina and western Slavonia.

Effect of NATO Actions

Another important and perhaps not as widely recognized issue was the role of NATO in the operation. Prior to the Operation, they were actively involved in tracking General Gotovina's movements and that of his army. NATO forces assisted in clearing Serb blockades and with logistical and communications issues. This occurred as a result of their wish to push the Serbs to the negotiating table, in Dayton, Ohio. See a discussion of NATO and United States operational problems.

Brijuni Talks

On July 31, 1995, a meeting Croatia’s top military and political leadership was held on the island of Brijuni.[33] Tudjman apparently spoke about "blows that will make the Serbs all but disappear, in other words, those we don’t reach immediately, must capitulate in the next few days."[34]

A video of the meeting later formed the basis of the United Nations war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia's indictments against the three Storm generals: Gotovina, Ivan Cermak and Mladen Markac. The Hague tribunal's prosecutors consider the content of the video as proof of existence of a criminal enterprise to forcibly remove the Serb population from Croatia.[34] According to them, the Brijuni Transcripts prove a joint criminal enterprise to forcibly remove Serbs from the area, to remove them through such means as shelling, destruction, looting, intimidation, and violence; although it is highly possible that in reality Tudjman spoke about Rebel Serb military only.[35]

The Croatian Chief State Prosecutor's Office has verified the authenticity of the recording of the Brijuni talks.[36][37]

It is important that these [Serb] civilians start moving and then the army will follow them, and when the columns start moving, they will have a psychological effect on each other. [...] We will inform them of what routes they can retreat through, but formulate it so as to cause confusion among them. [...] That means we provide them with an exit, while on the other hand we feign to guarantee civilian human rights and the like...

– Croatian President Franjo Tudjman[35][38]

Negotiations

Before the beginning of the operation, both sides were present at peace talks in Switzerland on 3 August 1995. Croatia's stance was for the Serbs to agree to reintegration into Croatia, which they refused, even though military action was expected.

In a special proclamation, the president of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman called for the Serb population which had not taken part in the war to remain in their homes and that their rights would be respected.[39][40] Croatian Army representatives also declared that they would leave corridors open for civilians wishing to flee to Bosnia. Throughout the Operation, the Army held regular news conferences, displaying maps of operations on the ground.

4 August 1995

At 0300 on 4 August, UN forces had been warned about Croatian attack which would start 2 hours later[41] when 150,000 Croatian Army troops attacked along a 300 km front. The Croatian 4th and 7th Guards Brigades broke through the lines of the Serb forces and advanced deep toward the capital. Much of the rebel Croatian Serb leadership had already left for Serbia and Bosnia.

Main attacks

The main part of the operation was conducted by Croatian Guard Brigades which had attacked at many different points in order to effectively split the RSK in few separate areas. For the opening phase of the operation, other units simply held the front, but would later surround and force surrender of remaining pockets of resistance.

In the main operation, the First Croatian Guard Brigade attacked toward Saborsko and Plitvice Lakes, with its objective being a linkup with Bosnia and Herzegovina troops who had attacked Krajina from the Bihać pocket. Simultaneously, the Second Croatian Guard Brigade attacked with the primary objective of capturing Glina and Petrinja, followed by a linkup with troops in the Žirovac area. During first day of fighting around Petrinja, 2nd Guards Brigade encountered unexpectedly stiff resistance and suffered heavy losses (18 guardsmen killed and 5 tanks destroyed). To solve the problem, President Tuđman gave general Petar Stipetić overall command in the region. He regrouped the units at his command and managed to defeat the enemy, although the rebels managed to evacuate most of their equipment.

The Fourth and Seventh Croatian Guard Brigades attacked from Bosnia and Herzegovina territory toward the capital Knin of Krajina. The bulk of the Ninth Croatian Guard Brigade attacked toward Ljubovo and Udbina, but a smaller part attacked from Velebit mountain toward Sveti Rok (taken on 4 August) and Gračac.

During the first day of fighting, a significant event was the cutting of the road Knin-Slunj, which blocked by the 21 Kordun Corps from supporting Krajina forces in Lika or Knin. Initially, resistance was strong — especially in the Kordun, Petrinja and Lika regions — but following the first day resistance collapsed and the bulk of the RSK army retreated.

Decision to evacuate civilians from towns along the front line in the Knin area

The rebel Serb Supreme Defence Council met under president Milan Martić to discuss the situation. A decision was reached at 16:45 to "start evacuating the population unfit for military service from the municipalities of Knin, Benkovac, Obrovac, Drniš and Gračac." These towns were along the front line in the southern tip of the RSK. The order further stated the evacuation was "to be carried out according to the plan towards direction of Knin and furthermore via Otrić, and towards Srb and Lapac", towns in the interior of the RSK near the Una River which marks the boundary with Bosnia-Herzegovina.[42]

Suppression of air defense by NATO

On the same day, "Two U. S. Navy EA-6Bs and two U. S. Navy F/A-18Cs", patrolling Croatian and Bosnian airspace as part of Operation Deny Flight to enforce no-fly zones, attacked two Serb surface-to-air missile radar sites near Knin and Udbina. The attack, using AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missiles, were "in self-defence after the aircraft electronic warning devices indicated they were being targeted by anti-aircraft missiles."[43]

5 August 1995

On 5 August, Knin and most of the Dalmatian hinterland were captured by Croatian forces, with only sporadic resistance encountered from the VSK.

The 5th Corps of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina started an offensive, attacking the VSK from the rear and crossing the border in multiple places from north-western Bosnia and linking up with the Croatian Army near the Plitvice Lakes, well inside Croatia.

Large refugee columns formed in many parts of Croatian Serb territory, so virtually the entire Serb population fled into Bosnia along the evacuation corridors established by the Croatian military under a cease-fire agreement brokered by the United Nations which, according to spokesman Philip Arnold, feared that assisting those fleeing the region would open UN to charges of contributing to ethnic cleansing.[44]

During battle for Knin 1000 civilians of Serb nationality would come under protection of UN forces. Of this number 340 would later stay in Croatia, 61 would be suspected by Croats of war crimes and arrested and the rest would leave for Serbia[45]

6 August 1995

On August 6, the Croatian 1st Guards Brigade and allied units of the Bosnian Army's 5th Corps continued to advance into rebel Serb-controlled territory near Slunj (north of Plitvice) and reached the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina. The towns of Petrinja, Kostajnica, Obrovac, Korenica, Slunj, Bruvno, Vrhovine, Plaški, Cetingrad, Plitvice and Glina were all captured during the course of the day. Strong resistance was only encountered in the town of Glina (south of Sisak). The Croatian-held town of Karlovac was subjected to retaliatory shelling by the VSK, and Bosnian Serb aircraft attacked a chemical plant in the town of Kutina. President Tuđman staged a triumphal entry into Knin, where the Croatian flag was raised above the fortress that dominates the old town.

7 August 1995

Fighting continued on 7 August but at a much lower intensity than on the previous days. Two Serb aircraft were shot down near Daruvar and Pakrac, and the towns of Turanj and Dvor na Uni were captured. Croatian and Bosnian army units linked up at Zirovać, to the east of the Bihać pocket. The Bosnian town of Velika Kladuša, which had been the "capital" of the self-proclaimed breakaway Republic of Western Bosnia (Bosniak forces of Fikret Abdić), was captured by Bosnian forces. In the evening, Croatian Defence Minister Gojko Šušak declared the end to major combat operations, as most of the border with Bosnia was controlled by the Croatian Army and only mopping-up actions remained to be completed.

8 August 1995 onwards

The last mopping-up actions took place on 8 August with the unopposed capture of Gornji Lapac, Donji Lapac and Vojnić. On 9 August, the surrounded VSK's 21st Corps (Kordun) surrendered en masse to the Croatian Army near Vojnić.[46][47]

By this time, virtually the entire Serb population of the Krajina was on the move, crossing into Serb-controlled territory in Bosnia. The exodus was complicated by the presence of armed Krajina Serb soldiers among the civilian refugees. A large refugee column that was moving on the Glina-Dvor road during August 1995 suffered casualties on two occasions: one report mentions Croatian army shelling of the column, and another mentions tanks of the Serbian 2nd Tank Brigade with Mile Novaković making their way through the road without regard to Serb civilians.[48]

The Croatian government claimed that around 90,000 Serb civilians had fled:

Upon instructions from my Government I have the honour to address you concerning a letter circulated as a document of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities

– E/CN.4/Sub.2/1995/45, dated 11 August 1995[49]

Serbian sources claimed that there were as many as 250,000 refugees. The United Nations put the figure at 150,000-200,000. The BBC reports the number to be 200,000 ([50] and[51])

On 21 August, Croatian Army reported that 174 Croatian soldiers had been killed in the offensive and 1,430 wounded[6] while Serbian loses were 700 soldiers killed.

Although after Operation Flash it has become clear that the Krajina army was known to be less capable than the Croatian Army, its lack of serious resistance has been surprise. The Croatian Army had reportedly expected at least a week's fighting. However, other than the fighting around Glina, the rebel Serb military response proved little more than symbolic in most places. The VSK largely collapsed, many of its soldiers deserting and joining the civilian exodus and others carrying their weapons into Bosnia. Around 5,000 were said to have surrendered and handed in their weapons to Croatian and UN forces.

Operation Storm did not target the Serb-occupied area of Eastern Slavonia, along the border with Serbia, which was the easternmost end of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina (though geographically disconnected from the other Serb-held areas of Croatia). Although there were fears of a direct military confrontation between Croatia and Serbia in Eastern Slavonia, large-scale armed conflict was not resumed in that region.

Aftermath

Military and political

In the days immediately following Operation Storm, Croatian Army and Ministry of the Interior (MUP) units conducted a series of follow-up operations in the Krajina region. The majority of the Croatian Army forces withdrew from the area in August 1995. After the operation, joint Croatian and Bosnian forces would continue the offensive in western Bosnia, advancing towards Bosnian Serb capital Banja Luka.

Operation Storm lifted the siege of Bihać. Bosnian general Atif Dudaković (commander of the Bihać 5th Corps) said that Operation Storm was an answer to the Split agreement signed by presidents Tudjman and Izetbegovic that pledged aid to the besieged pocket.[52]

Neither Serbian President Slobodan Milošević nor the Serb-dominated Yugoslav Army came to the aid of the Krajina Serbs during the offensive. Although Milošević condemned the Croatian military assault, the Serbian government-controlled press also attacked the Krajina Serb leaders, claiming they were unfit to hold office.[53]

Operation Storm was seen as a total reversal of the military balance of power in the region. Along with NATO's bombing campaign in Bosnia (Operation Deliberate Force), Operation Storm and its follow-up offensives in western Bosnia were seen as vital contributing factors to peace talks resuming, that would result with the Dayton Agreement a few months later.

In a highly publicized event, Croatia organized a Freedom Train; running from Zagreb to Knin as a symbol of a free and unified Croatia, since until Operations Flash and Storm, the country was effectively split into 2 segments with little or no land communication.

In 2005, Prime Minister of Croatia Ivo Sanader said, "Storm is a brilliant historical military and police operation that we can be proud of, the operation which liberated central parts of the occupied Croatia." Furthermore, he stated that if a sovereign country is occupied, it has the right to liberate its territory.

War crimes

During the Operation Storm and mainly in its aftermath between 116 (Croatian Helsinki Committee) and 1200 civilians (Serb statement) were killed and between 150.000 and 250.000 Serbs left the Krajina before the operation.[54] The difference in the numbers of murdered civilians might be explained by the fact, that the distinction between soldiers and civilians was difficult (e.g. Slobodan Lazarevic: "Everyone was to blame for something, no one could say that they had not done anything and, therefore, all had a reason to depart from Croatia").[55]

Out of the 122 Serbian Orthodox churches in the area, 17 were damaged, but only one was completely destroyed. According to a claim in the September 1995 communiqué from the Permanent Mission of Croatia to the U.N., most of the damage to the Orthodox churches occurred prior to the Serbian retreat.[56]

In the years following Operation Storm, Croatian authorities have uncovered over 3,000 bodies, presumed by the authorities to be murdered Croatians, in mass graves in the former Krajina territory, buried since the Serb ethnic cleansing campaign in 1991.[57]

In June 2008, during the prosecution of Ante Gotovina at the Hague, Canadian general Andrew Leslie claimed between 10,000 and 25,000 civilians were victims of the shelling of Knin on 4 and 5 August 1995. Mladen Markac’s defense counsel cited this as an example of gross exaggerations of Serb casualties by the UN personnel in the field. Canadian general Forand didn’t want to comment on Leslie’s claim, saying only that something like that was never registered in the situation reports drafted by the Sector South command.[58]

Refugees

Operation Storm caused an estimated 250.000 Serbs to be expelled from their homes and flee for Republic of Srpska and Serbia.[59]. Whether the exodus was forced to occur by advancing Croatian Armed Forces, or if there was another reason for emigration is a disputed matter.

Most Serbs fleeing the Krajina region went to Banja Luka or to Serbia proper. The majority of them were resettled in the Serbian province of Vojvodina, and a smaller number were in predominantly Albanian-populated Kosovo in southern Serbia.

In the first days after the offensive, Serbia accepted arriving refugees, but, starting between 12 and 13 August, the authorities conscripted able-bodied men who had recently arrived from the Krajina area and sent them to Serb-controlled territory in Bosnia and eastern Slavonia, assigned to Serbian armed forces there.[60] On 12 August, Serbia also announced that men of military age would no longer be allowed to cross from Bosnian Serb-controlled territory into Serbia proper, claiming that it had accepted 107,000 refugees from Krajina since 4 August.

Some of the RSK refugees were declared illegal migrants by FRY authorities and many were deported. Some were reportedly turned over by the police to paramilitary units of Željko Ražnatović, a.k.a. Arkan, in the latter's base in the village of Erdut in eastern Slavonia and reported being mistreated by Arkan's men. Reportedly, conscripted refugees taken to eastern Slavonia had been beaten and humiliated in public because they "surrendered Krajina to the enemy."[61]

The large influx of refugees raised local tensions and Vojvodina's sizable Croatian minority was harassed. Liberal opposition leaders in Vojvodina and Croatian government representatives in Belgrade, asserted that between 800 and 1,000 Croats left Vojvodina during August 1995 due to eviction and intimidations from Krajina refugees and local extremists.[62][63]

In The Guardian, Jonathan Steele wrote: "I remember being stunned at how quickly victims can turn into villains. In the town of Gibarac just inside the border of Serbia, I watched newly arrived Serb refugees being helped to find shelter by local relatives who went into homes and evicted Croatian families."[64]

Approximately 50,000 refugees remained in Bosnian Serb territory (largely in the Banja Luka area). In retaliation for their displacement, some refugees — with the assistance of Serbian paramilitary groups — forcibly evicted Croats and Muslims from their homes in the area. Other abuses — including execution and disappearance of non-Serbs — also intensified in the Bosanska Krajina area after the August 1995 offensive in Croatia. Local and regional Bosnian Serb authorities encouraged the expulsion of Croats and Muslims from the region, particularly in September and October 1995.[65]

Government of Republika Srpska has on other side ordered the expulsion of all Croats and Muslims from the Banja Luka region. Only exception are Croat and Muslim males of military age.[66] Croatia claims that in the weeks following the operation, over 1,000 Bosnian Croat families were expelled and many were tortured and killed as revenge.[67] Killings of non-Serbs took place in Bosnia (Banja Luka, Prijedor, Bosanski Novi, and Bosanska Dubica) in September and October, in part to make room for Serb refugees who fled after Operation Storm. Croats reportedly were particular targets for revenge. U.N. and other international observers collected numerous accounts of killings and other atrocities. Only about 3,000 Croats remained in Banja Luka after the war out of 29,000 that had lived there.[68]

Approximately 300,000 Croatian Serbs were displaced during the entire war, only a third of which (or about 117,000) are officially registered as having returned as of 2005[update]. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 200,000 Croatian refugees, mostly Croatian Serbs, are still displaced in neighbouring countries and elsewhere. Many Croatian Serbs cannot return because they have lost their tenancy rights and under threats of intimidation. Croatian Serbs continue to be the victim of discrimination in access to employment and with regard to other economic and social rights. Some cases of violence and harassment against Croatian Serbs continue to be reported.[69] Some of the Croatian Serbs will not return out of fear of being charged for war crimes, as the Croatian police has secret war crime suspect lists; Croatia passed an Amnesty law for anyone who had not taken an active part in the war, but many do not know if they are on amnesty list or not because amnesty rules are not clear enough.[70][71] The return of refugees is further complicated by the fact that many Croats and Bosniaks (some expelled from Bosnia) have taken residence in their vacated houses. Another reason for the non-return of refugees is the fact that areas that were under Croatian Serb control during the 1991-95 period were economically ruined (unemployment in RSK was 92%). Since that time, Croatia has started a series of projects aimed at rebuilding these areas and jump-starting the economy (including special tax exemptions), but unemployment is still high.

The primary Serb political party in Croatia, SDSS supports the current Croatian government and has made speeding up the return of refugees its main priority. The Croatian government has passed a number of laws aimed at enabling easier return to refugees.

Later events

The ICTY issued indictments against three senior Croatian commanders, Colonel General Ivan Čermak, Colonel General Mladen Markač and Brigadier (later General) Ante Gotovina. The three indictees were said to have had personal and command responsibility for war crimes carried out against rebel Serb civilians. It was later disclosed by the ICTY prosecutor, Louise Arbour, that had he not died when he did, Croatia's President Tuđman would probably also have been indicted.

Čermak and Markač were handed over to the ICTY, but Gotovina fled. He was widely believed to be at liberty in Croatia or the Croat-inhabited parts of Bosnia, where many view him as a hero, and his continued freedom was attributed to covert help from — or at least a "blind eye" turned by — the Croatian authorities. The US Government offered a $5 million reward for the capture of Ante Gotovina and he became one of the ICTY's most wanted men. The issue was a major stumbling block for Croatia's international relations. Its application to join the European Union was rebuffed in March 2005 due to the Croatian government's perceived complicity in Gotovina's continued evasion of the ICTY.

On 8 December 2005, Gotovina was captured by Spanish police in a hotel on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. He was transferred to Madrid for court proceedings before extradition to the ICTY at The Hague. The ICTY later joined the proceedings against the three generals into a single case. The trial started in March 2008.

Remembrance

In Croatia, the date August 5th was chosen as the Victory and Homeland Thanksgiving Day and the Day of Croatian Defenders. Conversely, in Serbia and Republika Srpska, commemorations are held for Serbs killed or exiled from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina during operation Storm.[72]

Battle figures

According to a Croatian source.[5]

Croatian forces and allies

Croatian Army (HV):

- 130,000 strong

- 80,000 soldiers in brigades, 70,000 in home guard regiments (domobranske pukovnije)

- 2nd echelon, 50,000

- 3rd echelon, 25 brigades

- 280 T-55 and 80 M-84 tanks

- 800 heavy artillery pieces

- 45-50 rocket launchers

- 18 MiG-21 "Fishbed" fighter jets

- 5 Mi-8 "Hip" transport helicopters

- 12 Mi-24D "Hind" attack helicopters

Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ABiH):

- 5th Corps (Bihać pocket forces — five Mountain Infantry brigades)

- 25,000 soldiers est.

- 15 T-55 tanks

- 80 heavy artillery pieces

Serbian forces and allies

Army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (VRSK)

- 40,000 strong

- 20,000 1st echelon

- 10,000 2nd echelon

- 10,000 3rd echelon

- 400 tanks (30 M-84, 2 T-72 MBT's, +200 T-55 + some T-34/85 tanks)

- 160 APC's and IFV's (M-60P, M-80A, BTR-50, BRDM-2 and BOV APC)

- 560 artillery pieces

- 28 Multi-rocket launchers (M-63 Plamen, M-77 Oganj and M-87 Orkan)

- 18 Soko Gazelle and Mi-8 helicopters

- 360 air defence weapons (SA-2, SA-7, SA-9, ZSU-57-2, BOV-3, Bofors L/70)

- 25 aircraft (G-2 Galeb, J-21 Jastreb, J-20 Kraguj and Utva 66)

Army of the Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia

- 10,000 strong (?)

See also

- Bosanska Posavina

- Operation Flash

- Operation Summer '95

- Operation Tiger

- Operation Mistral

- Operation Deliberate Force

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Leutloff-Grandits, Carolin: Claiming ownership in postwar Croatia: the dynamics of property relations and ethnic conflict in the Knin region. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2006, page 69. ISBN 3-8258-8049-4

- ↑ "Weary Bihac cries with joy as siege ends". The Independent. 1995-08-09. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/weary-bihac-cries-with-joy-as-siege-ends-1595403.html. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ↑ "After Long Siege, Bosnians Relish 'First Day of Freedom'". The New York Times. 1995-08-09. http://www.nytimes.com/1995/08/09/world/after-long-siege-bosnians-relish-first-day-of-freedom.html?pagewanted=1. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ↑ "Yugoslavia-Croatia ties". The New York Times. 1996-09-10. http://www.nytimes.com/1996/09/10/world/yugoslavia-croatia-ties.html?pagewanted=1. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 (Croatian) Croatian War of Independence 1995.08.04. - 08.08. - "Oluja"

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 http://www.b92.net/eng/news/in_focus.php?id=111&start=0&nav_id=35990

- ↑ Madey, Neven (14 August 1995). Letter from the Chargé d'affaires. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Accessed 5 September 2009.

- ↑ "Croatia: Impunity for Abuses Committed during "OPERATION STORM" and the denial of the Right of Refugees to return to the Krajina", Human Rights Watch 8 (13 (D)), August 1996, http://www.hrw.org/reports/1996/Croatia.htm

- ↑ Sisk, Robert (1995-08-05), "Two Navy Planes Fire on Serb Missile Sites", New York Daily News, http://www.fortunecity.com/meltingpot/greenside/761/168krajina95.html, retrieved 2008-04-13

- ↑ Adams, Thomas K. (Summer 1999), "The New Mercenaries and the Privatization of Conflict", Parameters (United States Army War College): 103–16, http://www.carlisle.army.mil/usawc/parameters/99summer/adams.htm

- ↑ Smith, Eugene B. (Winter, 2002), "The new condottieri and US policy: The Privatization of Conflict and its implications"", Parameters (United States Army War College): 5–6, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0IBR/is_4_32/ai_95447364/pg_5, retrieved 2008-04-13

- ↑ Bill Clinton, Voice of America Croatian, http://voanews.com/croatian/archive/2004-06/a-2004-06-22-11-1.cfm?renderforprint=1&textonly=1&&TEXTMODE=1&CFID=41216627&CFTOKEN=92342436

- ↑ Richard Holbrooke, Richard Holbrooke's book To End a War, http://www.amazon.ca/End-War-Richard-Holbrooke/dp/0375753605

- ↑ International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (2008-05-13), http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/got-ii010608e.htm

- ↑ Pearl, Daniel (2002), At Home in the World: Collected Writings from The Wall Street Journal, Simon and Schuster, p. 224, ISBN 074324415X, http://books.google.com/?id=BInS_EkHIUsC&printsec=frontcover, retrieved 2008-04-13

- ↑ " DISPUTE WITH EU NEGOTIATOR; Bildt has lost credibility as peace mediator — Foreign Ministry" BBC Summary of World Broadcasts 7 August 1995

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Fedarko, Kevin, et al. (August 14, 1995). "The Guns of August". Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,983292,00.html. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ↑ International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (2008-03-12) (PDF), Amended Joinder Indictment, Gotovina, Čermak and Markač, Case Number IT-06-90, http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/got-coramdjoind080312e.pdf, retrieved 2008-04-14

- ↑ Tanner, Marcus, "Croatia: A Nation Forged In War," New Haven: Yale Nota Bene; p.298

- ↑ ICTY census UNPA Sector East, http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/mil-ii011008e.htm

- ↑ Human Rights Watch Croatia, http://www.hrw.org/reports/1997/croatia/Croatia-02.htm

- ↑ U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE (January 31, 1994), CROATIA HUMAN RIGHTS PRACTICES, 1993; Section 2, part d., http://www.hri.org/docs/USSD-Rights/93/Croatia93.html

- ↑ United Nations Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights, SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE TERRITORY OF THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA, Section J, Points 147 and 150, http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/2848af408d01ec0ac1256609004e770b/5793c2d636a30ac9802566710057034c?OpenDocument

- ↑ United Nations Economic and Social Council, SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE TERRITORY OF THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA, Section K, Point 161, http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/2848af408d01ec0ac1256609004e770b/5793c2d636a30ac9802566710057034c?OpenDocument

- ↑ Institute For War and Peace Reporting, Milosevic Allegedly Angered by Zagreb Shelling, http://www.iwpr.net/?p=tri&s=f&o=259864&apc_state=henitri2006

- ↑ Press release: THE TRIBUNAL ISSUES AN INTERNATIONAL ARREST WARRANT AGAINST MILAN MARTIC, 8 March 1996, http://www.un.org/icty/pressreal/p042-e.htm

- ↑ Frustrated Croats Are Openly Preparing a Major Assault on a Serbian Enclave

- ↑ (PDF) Serb Leaders Proposals for Autonomy, http://www.ecmi.de/jemie/download/Focus3-2003_Caspersen.pdf

- ↑ Croatian Serbs Won't Even Look At Plan for Limited Autonomy

- ↑ ICTY against Milan Martic, http://www.un.org/icty/transe54/030626IT.htm

- ↑ CROATS CONFIDENT AS BATTLE LOOMS OVER SERBIAN AREA

- ↑ Vreme News Digest of 13 March 1995

- ↑ Ante Gotovina case, Friday, 27 February 2009 - ICTY

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Croatia: Former President 'planned ethnic cleansing of Serbs' The Centre For Peace In The Balkans, AKI (Italy), April 27, 2007

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Case against Gotovina, Monday, 23 March 2009 - ICTY

- ↑ Government Decides To Lift Classification Seal from Transcripts HRT

- ↑ Program with the surfaced recordings - HRT — Croatian National Television

- ↑ 17 Transcripts and Thousands of Pieces of Evidence Against the Generals, Nacional number 594, 2007-04-03

- ↑ Untitled Document

- ↑ The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=990CE6DA133FF936A15753C1A963958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all.

- ↑ AKCIJA HRVATSKE VOJSKE I REDARSTVENIH SNAGA TEČE PO PLANU

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (August 1996), CROATIA: IMPUNITY FOR ABUSES COMMITTED DURING "OPERATION STORM" AND THE DENIAL OF THE RIGHT OF REFUGEES TO RETURN TO THE KRAJINA, http://www.hrw.org/reports/1996/Croatia.htm

- ↑ NATO Regional Headquarters, Allied Forces Southern Europe, Operation Deny Flight, http://www.afsouth.nato.int/archives/operations/DenyFlight/DenyFlightFactSheet.htm

- ↑ Bonner, Raymond (1995-08-10). "'Frightened and Jeered At, Serbs Flee From Croatia'". NYT. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=990CE4DB143FF933A2575BC0A963958260&scp=7&sq=serbs%2C+croatia&st=nyt. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ GENERAL CERMAK O ODLASKU SRBA IZ VOJARNE UNCRO-A U KNINU

- ↑ http://www.scc.rutgers.edu/serbian_digest/202/t202-3.htm

- ↑ http://public.carnet.hr/mvp_news/hna/Kolovoz95/0809952.hna.html

- ↑ http://www.vecernji.hr/newsroom/news/croatia/3237469/index.do Serbian 2nd Tank Brigade making their way

- ↑ Neven Madey (15 August 1995). ""Letter from the Chargé d'affaires, a.i. of the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Croatia". United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights. http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/0/d0cd11bdf1350357802566d60046e3b7?Opendocument. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ↑ "Evicted Serbs remember Storm". BBC News. 5 August 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4747379.stm. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "Croatia marks Storm anniversary". BBC News. 5 August 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4125640.stm. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "'We needed Operation Storm as much as Croatia did'". interview with General Atif Dudakovic. Bosnian Institute. 2006-09-11. http://www.bosnia.org.uk/news/news_body.cfm?newsid=2225. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Michael (1995-09-05). "Serbia Demands International Action". The Independent.

- ↑ Henry Jackson Society

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Blaskovich, Jerry (1997), Anatomy of deceit: an American physician's first-hand encounter with the realities of the war in Croatia, New York: Dunhill Publishing, ISBN 0-935016-24-4

- ↑ Crown Home Page

- ↑ http://www.sense-agency.com/en/press/printarticle.php?pid=11980

- ↑ http://www.groundreport.com/World/Croatia-marks-Anniversary-of-Operation-Storm/2866849

- ↑ Judah, Tim (1995-09-18). "Able-Bodied Refugees Are Forced Back to the Fight". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ "Spotlight Report No. 20: Violations of Refugees Rights in Serbia and Montenegro". Humanitarian Law Center/Humanitarian Law Fund. October 1995. p. 11.

- ↑ "Helsinki interview with Ivo Kujundzic, Counsellor for Humanitarian Affairs, and Davor Vidis, Spokesperson, Office of the Government of the Republic of Croatia, Belgrade, Serbia", Human Rights Watch, September 11, 1995

- ↑ "Helsinki interview with Nenad Canak, President of the Social Democratic League of Vojvodina, Novi Sad, Vojvodina, Serbia", Human Rights Watch, 31 August 1995

- ↑ Steele, Jonathan (1999-06-14). "Break the cycle of abuse". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/1999/jun/14/balkans11.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, "Northwestern Bosnia: Human Rights Abuses during a Cease-Fire and Peace Negotiations," (A Human Rights Watch Short Report, vol. 8, no. 1, February 1996)

- ↑ Patrick Moore (1995-08-15). ""Sinister" development in Banja Luka exodus". OMRI Daily Digest. http://www.b-info.com/places/Bulgaria/news/95-08/aug15.omri. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ↑ Neven Madey (1995-08-14). "Letter from Croatian Government Chargé d'affaires". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/0/d0cd11bdf1350357802566d60046e3b7?Opendocument. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Gordana Katana (2003-06-20). "Bosnia: Papal Boost for Banja Luka". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. http://www.iwpr.net/?p=bcr&s=f&o=156849&apc_state=henibcr2003. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Amnesty International. (2005-08-04) Croatia: Operation "Storm" - still no justice ten years on. Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ http://www.hrw.org/worldreport99/europe/croatia.html

- ↑ http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/1996/19960522.sc6222.html

- ↑ Politika: A dirge for killed in Storm held in St. Mark's Church

References

- RSK, Vrhovni savjet odbrane, Knin, 4. avgust 1995., 16.45 časova, Broj 2-3113-1/95. The faximile of this document was published in: Rade Bulat "Srbi nepoželjni u Hrvatskoj", Naš glas (Zagreb), br. 8.-9., septembar 1995., p. 90.-96. (the faximile is on the page 93.).

- Vrhovni savjet odbrane RSK (The Supreme Council of Defense of Republic of Serb Krajina) brought a decision 4. August 1995 in 16.45. This decision was signed by Milan Martić and later verified in Glavni štab SVK (Headquarters of Republic of Serb Krajina Army) in 17.20.

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-82/95., Knin, 02.08.1995., HDA, Dokumentacija RSK, kut. 265

- This is the document of Republic headquarters of Civil Protection of RSK. In this document it was ordered to all subordinated headquarters of RSK to immediately give all reports about preparations for the evacuation, sheltering and taking care of evacuated civilians ("evakuacija, sklanjanje i zbrinjavanje") (the deadline for the report was 3. August 1995 in 19 h).

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-83/95., Knin, 02.08.1995., Pripreme za evakuaciju materijalnih, kulturnih i drugih dobara (The preparations for the evacuation of material, cultural and other goods), HDA, Dokumentacija RSK, kut. 265

- This was the next order from the Republican HQ of Civil Protection.

- It was referred to all Municipal Headquarters of Civil Protection. In that document was ordered to all subordinated HQ's to implement the preparation of evacuation of all material and all mobile cultural goods, archives, evidentions and materials that are highly confidential/top secret, money, lists of valuable stuff (?)("vrednosni popisi") and referring documentations.

- Drago Kovačević, "Kavez — Krajina u dogovorenom ratu" , Beograd 2003. , p. 93.-94.

- Milisav Sekulić, "Knin je pao u Beogradu" , Bad Vilbel 2001., p. 171.-246., p. 179.

- Marko Vrcelj, "Rat za Srpsku Krajinu 1991-95" , Beograd 2002., p. 212.-222.

External links

- "Former Yugoslavia: Can video play a part in truth, justice and reconciliation?" 6 November 2006, Gavin Simpson [2]

- BBC: Evicted Serbs remember Storm

- NGO Organization, Member of United Nations: US Officials aided and abetted Croatian General Ante Gotovina

- Dossier "Storm"

- Croatian Radio Television: News from operation Storm '95

- Yugoslav Report on Croatian army and police crimes in Krajina in 1995

- Amnesty international article about Operation Storm

- Chronology of Operation Storm

- Operation Storm Destroyed "Greater Serbia", Balkan Insight 20 January 2006

- Video taken during abuse of captured Serb soldiers and civilians. First killing is committed by the members of ABiH (Bosniaks) and second is the search for disguised Serbian soldiers by the members of HV (Croatian Army), where no killings are recorded. Download 33 MB RealMedia File

- Video taken after Serbian 2nd Tank Brigade made their way through civilians

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | Timeline | Participants | People |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Wars and conflicts

Background:

Consequences:

Articles on nationalism:

|

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 |

Ex-Yugoslav republics:

Unrecognised entities:

United Nations protectorate:

Armies:

Military formations and volunteers:

External factors: |

Politicians:

Top military commanders:

Other notable commanders:

Key foreign figures: |