Ram Narayan

| Ram Narayan | |

|---|---|

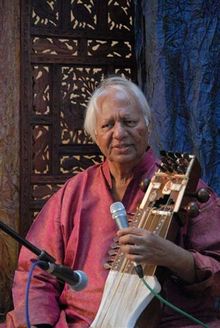

Narayan at Thames Valley University, Slough, England, in May 2007 |

|

| Background information | |

| Born | 25 December 1927 Udaipur, Mewar, British Raj |

| Genres | Hindustani classical music |

| Instruments | sarangi |

| Years active | 1944–present |

| Associated acts | Abdul Wahid Khan, Brij Narayan, Chatur Lal, Suresh Talwalkar, Aruna Narayan |

| Website | Pandit Ram Narayan |

Ram Narayan (Hindi: राम नारायण; IAST: Rām Nārāyaṇ, IPA: [ɾam naɾajn]) (born 25 December 1927), often referred to by the title Pandit, is an Indian musician who popularized the bowed instrument sarangi as a solo concert instrument in Hindustani classical music and became the first internationally successful sarangi player.

Narayan was born in Udaipur and learned to play the sarangi at an early age. He studied under sarangi players and singers and, as a teenager, worked as a music teacher and traveling musician. All India Radio, Lahore, hired Narayan as an accompanist for vocalists in 1944. He moved to Delhi following the partition of India in 1947, but wishing to go beyond accompaniment and frustrated with his supporting role, Narayan moved to Mumbai in 1949 to work in Indian cinema.

After an unsuccessful attempt in 1954, Narayan became a concert solo artist in 1956, and later gave up accompaniment. He recorded solo albums and began to tour America and Europe in the 1960s. Narayan taught Indian and foreign students and performed, frequently outside of India, into the 2000s. He was awarded India's second highest civilian honor, the Padma Vibhushan, in 2005.

Contents |

Early life

Ram Narayan was born on 25 December 1927 in Udaipur in northwestern India.[1] His great-great-grandfather, Bagaji Biyavat, was a singer from Amber, and he and Narayan's great-grandfather, Sagad Danji Biyavat, sang at the court of the Maharana of Udaipur.[1] Narayan's grandfather, Har Lalji Biyavat, and father, Nathuji Biyavat, were farmers and singers, Nathuji played the bowed instrument dilruba, and Narayan's mother was a music lover.[2] Narayan's first language was Rajasthani and he learned Hindi and, later, English.[3][4] At an age of about six, he found a small sarangi left by the family's Ganga guru, a genealogist, and was taught a fingering technique developed by his father.[5][6] Narayan's father taught him, but was worried about the difficulty of playing the sarangi and its association with courtesan music, which gave the instrument a low social status.[2][7] After a year, Biyavat sought lessons for his son from sarangi player Mehboob Khan of Jaipur, but changed his mind when Khan told him Narayan would have to change his fingering technique.[6] Narayan's father later encouraged him to leave school and devote himself to playing the sarangi.[5]

At about 10 years of age, Narayan learned the basics of dhrupad, the oldest genre of Hindustani classical music, by observing and imitating the practice of sarangi player Uday Lal of Udaipur, a student of dhrupad singers Allabande and Zakiruddin Dagar.[6][8] Giridhari Lal and Jahauddin Khan were other teachers of whom Narayan learned in Udaipur.[9] After Uday Lal died of old age, Narayan met traveling singer Madhav Prasad, originally of Lucknow, who had performed at the court of Maihar.[10][11] With Prasad, Narayan enacted the ganda bandhan, a traditional ceremony of acceptance between a teacher and his pupil, in which Narayan swore obedience in exchange for being maintained by Prasad.[12] He served Prasad and was taught in khyal, the predominate genre of Hindustani classical music, but returned to Udaipur after four years to teach music school.[8][10] Prasad later visited Narayan and convinced him to resign his position and dedicate his time to improvement as a musician, although the idea of giving up a secure existence for the life of a traveling musician was not well received by Narayan's family.[10][11] He stayed with Prasad and traveled to several Indian states until Prasad fell ill and advised him to learn from singer Abdul Wahid Khan in Lahore.[10][13] Following Prasad's death in Lucknow, Narayan enacted the ganda bandhan with another teacher who gave him lessons, but Narayan soon left for Lahore and never performed the ritual again.[12]

Career

Narayan traveled to Lahore in 1944 to find work in a film studio, but was unsuccessful.[10] He auditioned for the local All India Radio (AIR) as a singer, but the station's music producer, Jivan Lal Mattoo, noticed grooves in Narayan's fingernails:[10] sarangis are played by pressing the fingernails sideways against three playing strings, which strains the nails.[14] Mattoo instead employed Narayan to accompany vocalists on the sarangi.[10] Traditionally, the sarangi and other stringed instruments as well as the harmonium are supposed to play after the singer, imitate the vocal performance, and fill in gaps between phrases, when the singer breathes and prepares a new phrase.[15] Mattoo gave Narayan a room to stay in, guided his training, and later helped him contact khyal singer Abdul Wahid Khan, a rigorous teacher under whom Narayan learned four ragas through singing lessons.[7][10][16] Narayan was allowed occasional solo performances on AIR and had begun thinking of a solo career.[17]

After the partition of India in 1947, Narayan moved to Delhi and played at the local AIR station.[18] His work for popular singers increased his repertoire and knowledge of styles.[19] Narayan played with the classical singers Omkarnath Thakur, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Hirabai Badodekar, and Krishnarao Shankar Pandit, and he accompanied singer Amir Khan in 1948, when Khan sang for the first time at AIR Delhi following the partition.[20][21] As an accompanist for vocalists, Narayan showed his own skill and refused to stay in the background.[17] He became notorious among the vocalists of the city, who complained he was not a consistent accompanist and too assertive, but he maintained he wanted to keep singers in tune and inspire them in a friendly competition.[7][22] Other tabla (percussion) players and singers, including Omkarnath Thakur and Krishnarao Shankar Pandit, publicly expressed admiration for Narayan's playing.[23]

Narayan became frustrated with his supporting role for vocalists and moved to Mumbai in 1949 to freelance in film music and recording.[18][24] He recorded three solo 78 rpm gramophone records for the British HMV Group in 1950 and an early 10 inch LP album in Mumbai in 1951, but the album was not in demand.[18][25][26] Narayan's compositions and performances were popular in the Mumbai film industry, which offered a steady salary and anonymity for work that would have lowered his standing among classical musicians.[27] For the next 15 years he played and composed songs for films; Narayan composed for Humdard, Adalat, Milan, and Gunga Jumna, and played for Adalat, Noorjehan, Mughal-e-Azam, and Kashmir Ki Kali, among others.[28][29][30] He was considered a favorite of film music director O. P. Nayyar.[29]

Narayan performed in Afghanistan in 1952 and in China in 1954 and was well received in both countries.[31] His first solo concert at a 1954 music festival in the Cowasji Jehangir Hall, Mumbai, was cut short when an impatient audience, waiting for performances by famous artists, drove him from the stage.[26][32] Narayan contemplated giving up the sarangi and becoming a singer.[32] He later regained confidence, performed solo for smaller crowds, and was favorably received in his second attempt to play solo for a Mumbai music festival in 1956.[19][32] Narayan gave up accompaniment in the early 1960s; this decision carried a financial risk, because demand for solo sarangi had yet to be created.[33][34]

After sitar player Ravi Shankar successfully performed in Western countries, Narayan followed his example.[35] He recorded solo albums and made his first international tour in 1964 to America and Europe with his older brother Chatur Lal, a tabla player who had toured with Shankar in the 1950s.[24][36] The European tour included performances in France, Germany, sponsored by the Goethe-Institut, and at the City of London Festival, England.[37] Beginning in the 1960s, Narayan often taught and gave concerts outside of India.[4] On his Western tours he encountered interest in the sarangi because of its similarity to cello and violin.[38] The tabla player Suresh Talwalkar became a frequent accompanist for Narayan in the late 1960s.[39] Narayan continued to perform and record in India and abroad for the next decades and his recordings appeared on Indian, American, and European labels.[19][24] During the early 1980s he typically spent months each year visiting Western nations.[31] Narayan performed less frequently in the 2000s.[40]

Style

Narayan's style is typical of Hindustani classical music, but his choice of solo instrument and his background of learning from teachers outside his community are unusual for the genre.[24][42] He has stated that he sees it as his function to please an audience and lead it to stimulation or a state of peace of mind, and expects the audience to reciprocate by reacting to his playing.[43]

Narayan's performances are a combination of slow and serious alap (non-metrical introduction) and jor (performance with pulse) in dhrupad style, followed by a faster and less reserved gat section (composition with rhythmic pattern provided by the tabla) in khyal style.[44] He experimented with a style of jhala (performance with rapid pulse) developed by Bundu Khan, but considered it better suited for plucked instruments and stopped performing it.[45] The gat section includes one or two parts with compositions.[46] When two gats are used, the first one is at a slow or medium tempo, and the second one is faster; the gats are usually in the 16-beat rhythmic cycle tintal.[44][47] Narayan often concludes performances with ragas associated with thumri (a popular light classical genre), which are referred to as mishra (Sanskrit: mixed), because they allow for additional notes.[44] Narayan has stated that he does not consider his versions to be thumri because they are not derived from vocal compositions.[44]

Narayan practices and teaches using a limited number of paltas, exercises in a small scale range that are used to prepare playing different numbers of notes per bow.[48] Derived from paltas are lengthy note patterns called tans, which contain characteristic "melodic shapes" and are used by Narayan for fast playing.[49] He uses his left (fingering) hand for runs and to play an extended melodic range, and his right (bowing) hand for rhythmic accentuations.[19] Narayan's fingering technique, his low right hand position, keeping the bow in a close to right angle to the string, and his use of the full bow length are uncommon among sarangi players.[50]

Narayan is associated with the Kirana gharana (stylistic school of Kirana) through Abdul Wahid Khan, but his performance style is not strongly connected to it and has been described as eclectic.[51] Most of Narayan's compositions are from the vocal repertoire of his teachers and modified and adapted to the sarangi.[46] He has created original compositions and in performance varies those he was taught.[52] Narayan disfavors the creation of new ragas, but developed compound ragas, including those of Nand with Kedar and Kafi with Malhar.[52]

Narayan uses a sarangi obtained from Uday Lal and built in Meerut in the 1920s or 1930s in his concerts and recordings.[53] He plays on foreign harp strings to produce a clearer tone.[54] Narayan experimented with modifications to his instrument and added a fourth string, but removed it because it hindered fast playing.[55] In the 1940s, he substituted gut with steel for the first string and found it easier to play, but reverted to using only gut strings because the steel string altered the sound of the sarangi.[55]

Contributions and recognition

Narayan increased the status of the sarangi to that of a modern concert solo instrument, made it known outside of India, and was the first sarangi player with international success, an example later followed by Sultan Khan.[19][56][57] Narayan's simplified fingering technique allows for glide (meend)[58] and influenced the contemporary sarangi concert style, as aspects of his playing and tone production were adapted by sarangi players from Narayan's recordings.[3]

Narayan taught at Wesleyan University, Connecticut, and Mills College, California, in 1968, and at the American Society for Eastern Arts and the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Mumbai in the 1970s and 1980s, where he gave the first master class for sarangi.[24][59][60][61] Narayan privately trained sarangi players, including his daughter Aruna Narayan Kalle, his grandson Harsh Narayan, and Vasanti Srikhande.[62][63][64] He also taught sarod players,[65][66] including his son Brij Narayan, as well as vocalists[67][68][69] and a violinist.[70] In 2002, he taught 15 Indian students and more than 500 students in the United States and Europe had studied with him.[71] Indian Music in Performance: a practical introduction, released in 1980 by Neil Sorrell in cooperation with Narayan, was described as "one of the best presentations on modern North Indian music practice" by Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart.[19]

"My mission was to obliterate the blemish which the sarangi carried due to its social origins. I hope I have succeeded in this."[20]

Narayan argued that recognition of him and the sarangi came only after acceptance by the Western audience.[72] He attributed the lack of sarangi students to a lack of competent teachers and said that the Indian government should assist in preserving the instrument.[72][73] The Pt (Pandit) Ram Narayan Foundation in Mumbai offers scholarships and teaches sarangi, but Narayan stated he was skeptical the sarangi would survive.[40][74]

Narayan received the national awards Padma Shri in 1976, Padma Bhushan in 1991, and Padma Vibhushan in 2005.[75] The Padma Vibhushan, India's second highest civilian honor, was presented by Indian President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam.[76] Narayan was awarded the Rajasthan Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for 1974–75, the national Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for 1975, and was made a fellow of the Rajasthan Sangeet Natak Akademi for 1988–89.[77][78] He received the Kalidas Samman from the Government of Madhya Pradesh for 1991–92 and was presented with the Aditya Vikram Birla Kalashikhar Puraskar in 1999 by P. C. Alexander, governor of Maharashtra.[79][80] He also received the Maharashtra Gaurav Puraskar, the Shiromani Award, and the Rajasthan Welfare Association Award.[81] The biographical film Pandit Ramnarayan – Sarangi Ke Sang was shown at the 2007 International Film Festival of India.[82]

Family and personal life

Narayan shared a close personal and musical relationship with his older brother, Chatur Lal, who learned the tabla primarily to accompany his brother's sarangi playing.[36] Lal studied under tabla teachers in his youth, but later turned to farming.[36] Lal visited Narayan 1948 in Delhi after Narayan had become a professional sarangi player, and Narayan convinced Lal to work as a tabla player at the local AIR station.[36] Lal became an acclaimed musician, toured with instrumentalists Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan in the 1950s, and helped popularize the tabla in Western countries.[83] When Lal died in October 1965, Narayan had difficulty performing and struggled with alcoholism, but overcame the addiction after two years.[36] Narayan assisted his brother's four children after their father's death.[30] Chatur Lal's son, Charanjit Lal Biyavat, is a tabla player and has toured Europe with Narayan.[51]

Narayan's wife Sheela, a homemaker, came to Mumbai in the 1950s and they had four children.[26][30][84] She died prior to 2001.[63] His oldest son, sarod player Brij Narayan, was born on 25 April 1952 in Udaipur, and his daughter Aruna Narayan was born 1959 in Mumbai.[65][85] She was the first woman to give a solo sarangi concert and immigrated to Canada in 1984.[62][86] Another son, Shiv, is a year younger than Aruna, has learned to play the tabla, and toured Australia with his father.[87] Brij Narayan's son, Harsh Narayan, plays the sarangi.[71] In 2009, Narayan performed at BBC's The Proms in the Royal Albert Hall, London, with Aruna, and he played at the 2010 Sawai Gandharva Music Festival, Pune, with Harsh.[88][89]

Narayan is a Hindu and has stated "music is my religion", arguing that there was no better approach to divinity than music.[43] He is based in Mumbai.[72]

Discography

Writings

- Sorrell, Neil; Narayan, Ram (1980). Indian Music in Performance: a practical introduction. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719007569.

- Narayan, Ram (2009) (in Hindi). एक सुर मेरा एक सारंगी का. New Delhi: Kitabghar Prakashan. ISBN 8190722123.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 11

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 13

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Qureshi 2007, p. 108

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Qureshi 2007, p. 109

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 14

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bor 1987, p. 149

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Sorrell 2001, p. 637

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bor 1999, p. 180

- ↑ "Childhood and Training". Pandit Ram Narayan (Official website). Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5oFg2biBM. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Bor 1987, p. 151

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 15

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 17

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 16

- ↑ Bor 1987, p. 30

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 21

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 19

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 20

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Bor 1987, p. 152

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 Neuhoff 2006, pp. 911–912

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Dhaneshwar, Amarendra (18 February 2002). "Saviour of the sarangi, Pandit Ram Narayan". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUScyGGB. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Qureshi 2007, p. 116

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 20–22

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 22

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Qureshi 2007, p. 107

- ↑ Chandvankar, Suresh (3 May 2004). "LP/EP Records". Screen. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5pzDTjKmV. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Ghosh, Soma (November 2008). "एक जुनून है सारंगी [Sarangi is a passion]" (in Hindi). Dainik Jagran (Yahoo! India). Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUSjcWUo. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Qureshi 2007, p. 17

- ↑ Qureshi 2007, p. 119

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Suryanarayan, Renuka (27 October 2002). "Sarangi maestro returns to where it began". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUShpePA. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "An Interview with Pandit Ram Narayan". Pandit Ram Narayan (Official website). Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5n5BHIfXo. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 25

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Sorrell 1980, p. 24

- ↑ Bor 1987, p. 153

- ↑ Neuman 1990, pp. 93, 263

- ↑ Bor 1992, p. 48

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Sorrell 1980, p. 26–27

- ↑ "Narayan To Give Concert Friday Night". The Gettysburg Times. 6 November 1968. p. 1. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=fEcmAAAAIBAJ&pg=3407,5609965.

- ↑ Roy 2004, p. 206

- ↑ "Narayan, maître du sarangi, en récital à Montréal [Narayan, master of sarangi, performs in Montreal]" (in French). Le Devoir. 27 November 1981. p. 18. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=_DI0AAAAIBAJ&pg=1201,5549775.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Patil, Vrinda (9 December 2000). "Dying strains of sarangi". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUSoNQRR. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Bor 1999, p. 90

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. viii

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 29–31

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Sorrell 1980, p. 125

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 111

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 123

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 126

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, pp. 70–71

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 75

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 63

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 28

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Sorrell 1980, pp. 127–128

- ↑ Sorrell 1980, p. 55

- ↑ Neuman 1990, p. 228

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Sorrell 1980, p. 56

- ↑ Slawek 2000, p. 207

- ↑ Bor 1992, p. 78

- ↑ Bor 1987, pp. 34–35

- ↑ Massey 1996, p. 159

- ↑ Qureshi 2007, p. 130

- ↑ Qureshi 2007, p. 110

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Qureshi 2007, p. 126

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Qureshi 2007, p. 133

- ↑ Pratap, Jitendra (7 October 2005). "Juggling with jugalbandis". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUSqd4Je. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Magic in his fingers". Screen. 14 November 2003. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5pzDWK9Kl. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ Sharma, S. D. (5 February 2009). "Basant beats". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUSuR73i. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Govind, Ranjani (1 May 2008). "Varied emotions". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUSwAha6. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Rajan, Anjana (18 February 2005). "When the skylark sings". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUSythtg. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "Quality music is forever". The Tribune. 3 November 2000. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUT646QW. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Sinha, Manjari (27 February 2009). "Tunes of friendship". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUT8zaSo. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Suryanarayan, Renuka (7 September 2002). "Sarangi at its best". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTBGjfZ. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Sharma, S. D. (28 February 2008). "Sarangi maestro calls present music soulless drudgery". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTHyD40. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Bor 1987, p. 118

- ↑ Tandon, Aditi (25 March 2006). "Preserving traditional melodies". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTK8AO6. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "Padma Awards". Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTOD087. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "President presents Padma awards". The Hindu. 29 March 2005. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTRz71f. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "Awardees". Rajasthan Sangeet Natak Akademi. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5oiJocIEE. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ "SNA: List of Akademi Awardees – Instrumental – Sarangi". Sangeet Natak Akademi. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTVnMVi. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "राष्ट्रीय कालिदास सम्मान [Rashtriya Kalidas Samman]" (in Hindi). Department of Public Relations of Madhya Pradesh. 2006. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTg6OvI. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "Sarangi maestro Pt Ram Narayan gets Aditya Birla award". The Indian Express. 15 November 1999. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTlATnL. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Shah, Kinjal (4 October 2008). "Strung together". The Times of West Mumbai. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUToURe0. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "Films about India's creative legends at IFFI". Indo-Asian News Service (Hindustan Times). 28 November 2007. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P3-1389699451.html. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ Naimpalli 2005, p. 107

- ↑ Qureshi 2007, p. 131

- ↑ Harvey, Jane (1995). "The sarangi today", p. 5 [CD booklet]. Album notes for Raga Bairagi Bhairav, Raga Shuddh Sarang, Raga Madhuvanti by Aruna Narayan. United Kingdom: Nimbus Records (NI 5447).

- ↑ Nair, Malini (10 March 2010). "Serenading solo". Daily News & Analysis. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTv15U2. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Murdoch, Anna (22 September 1986). "Music lesson for the West". The Age. p. 14. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=vbMnAAAAIBAJ&pg=2234,124944.

- ↑ Hewett, Ivan (17 August 2009). "BBC Proms 2009: Indian Voices – review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUTybuDt. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "Sarangi, sitar maestros regale Puneites". Times News Network (The Times of India). 11 January 2010. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5rUU2BrPi. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

References

- Bor, Joep (1 March 1987). "The Voice of the Sarangi". Quarterly Journal (Mumbai, India: National Centre for the Performing Arts) 15, 16 (3, 4; 1).

- Bor, Joep; Bruguiere, Philippe (1992). Masters of Raga. Berlin: Haus der Kulturen der Welt. ISBN 3803005019.

- Bor, Joep; Rao, Suvarnalata; Van der Meer, Wim; Harvey, Jane (1999). The Raga Guide. Nimbus Records. ISBN 0954397606.

- Massey, Reginald (1996). The Music of India. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 8170173329.

- Naimpalli, Sadanand (2005). Theory and Practice of Tabla. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 8179911497.

- Neuhoff, Hans (2006). "Narayan, Ram". In Finscher, Ludwig (in German). Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik. 12 (2nd ed.). Bärenreiter. ISBN 3761811225.

- Neuman, Daniel M. (1990) [1980]. The Life of Music in North India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226575160.

- Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt (2007). Master musicians of India: hereditary sarangi players speak. Routledge. ISBN 0415972027.

- Roy, Ashok (2004). Music Makers: Living Legends of Indian Classical Music. Rupa & Co.. ISBN 8129103192.

- Slawek, Stephen (2000). "Hindustani Instrumental Music". In Arnold, Alison. The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent. 5. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0824049462.

- Sorrell, Neil; Narayan, Ram (1980). Indian Music in Performance: a practical introduction. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719007569.

- Sorrell, Neil (2001). "Narayan, Ram". In Sadie, Stanley. The New Grove dictionary of music and musicians. 17 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0333608003.

External links

- "Pandit Ram Narayan". Official website. http://ramnarayansarangi.com/.

- Ram Narayan at Allmusic