Shakespeare's sonnets

| Shakespeare's Sonnets | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Author | William Shakespeare |

| Country | England |

| Language | Early Modern English |

| Genre(s) | Renaissance poetry |

| Publisher | Thomas Thorpe |

| Publication date | 1609 |

Shakespeare's sonnets are 154 poems in sonnet form written by William Shakespeare that deal with such themes as the passage of time, love, beauty and mortality. All but two of the poems were first published in a 1609 quarto entitled SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS.: Never before imprinted. Sonnets 138 and 144 had previously been published in a 1599 miscellany entitled The Passionate Pilgrim. The quarto ends with "A Lover's Complaint", a narrative poem of 47 seven-line stanzas written in rhyme royal.

The first 17 sonnets, traditionally called the procreation sonnets, are ostensibly written to a young man urging him to marry and have children in order to immortalise his beauty by passing it to the next generation.[1] Other sonnets express the speaker's love for a young man; brood upon loneliness, death, and the transience of life; seem to criticise the young man for preferring a rival poet; express ambiguous feelings for the speaker's mistress; and pun on the poet's name. The final two sonnets are allegorical treatments of Greek epigrams referring to the "little Love-god" Cupid.

The publisher, Thomas Thorpe, entered the book in the Stationers' Register on 20 May 1609:

Tho. Thorpe. Entred for his copie under the handes of master Wilson and master Lownes Wardenes a booke called Shakespeares sonnettes vjd.

Whether Thorpe used an authorized manuscript from Shakespeare or an unauthorized copy is unknown. George Eld printed the quarto, and the run was divided between the booksellers William Aspley and John Wright.

Contents |

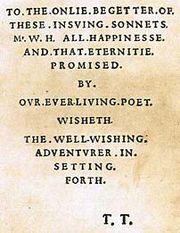

Dedication

The sonnets include a dedication to one "Mr. W.H.". The identity of this person remain a mystery and has provoked a great deal of speculation.

The dedication reads:

| “ |

TO.THE.ONLIE.BEGETTER.OF. T.T. |

” |

Given its obliquity, since the 19th century the dedication has become, in Colin Burrow's words, a 'dank pit in which speculation wallows and founders'. Don Foster concludes that the result of all the speculation has yielded only two "facts," which themselves have been the object of much debate: First, that the form of address (Mr.) suggests that W.H. was an untitled gentleman, and second, that W.H., whoever he was, is identified as "the only begetter" of Shakespeare's Sonnets (whatever the word "begetter" is taken to mean).[2]

The initials 'T.T.' are taken to refer to the publisher, Thomas Thorpe, though Thorpe usually signed prefatory matter only if the author was out of the country or dead.[3] Foster points out, however, that Thorpe's entire corpus of such consists of only four dedications and three stationer's prefaces.[4]. That Thorpe signed the dedication rather than the author is seen as evidence that he published the work without obtaining Shakespeare's permission.[5]

The capital letters and periods following each word were probably intended to resemble an ancient Roman lapidary inscription or monumental brass, thereby accentuating Shakespeare's declaration in Sonnet 55 that the work will confer immortality to the subjects of the work:[6]

- Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

- Of princes shall outlive this pow'rful rhyme,

126 of Shakespeare's sonnets are addressed to a young man (often called the "Fair Youth"). Broadly speaking, there are two branches of theories concerning the identity of Mr. W.H.: those that take him to be identical to the youth, and those that assert him to be a separate person.

The following is a non-exhaustive list of contenders:

- William Herbert (the Earl of Pembroke). Herbert is seen by many as the most likely candidate, since he was also the dedicatee of the First Folio of Shakespeare's works. However the "obsequious" Thorpe would be unlikely to have addressed a lord as "Mr".[7]

- Henry Wriothesley (the Earl of Southampton). Many have argued that 'W.H.' is Southampton's initials reversed, and that he is a likely candidate as he was the dedicatee of Shakespeare's poems Venus & Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. Southampton was also known for his good looks, and has often been argued to be the 'fair youth' of the sonnets. The reservations about "Mr." also apply here.

- A simple printing error for Shakespeare's initials, 'W.S.' or 'W. Sh'. This was suggested by Bertrand Russell in his memoirs, and also by Foster[8] and by Jonathan Bate[9]. Bate supports his point by reading 'onlie' as something like 'peerless', 'singular' and 'begetter' as 'maker', ie. 'writer'. Foster takes "onlie" to mean only one, which he argues eliminates any particular subject of the poems, since they are addressed to more than one person. The phrase 'Our Ever-Living Poet', according to Foster, refers to God, not Shakespeare. 'Poet' comes from the Greek 'poetes' which means 'maker', a fact remarked upon in various contemporary texts; also, in Elizabethan English the word 'maker' was used to mean 'poet'. These researcher believe the phrase 'our ever-living poet' might easily have been taken to mean 'our immortal maker' (God). The 'eternity' promised us by our immortal maker would then be the eternal life that is promised us by God, and the dedication would conform with the standard formula of the time, according to which one person wished another 'happiness [in this life] and eternal bliss [in heaven]'. Shakespeare himself, on this reading, is 'Mr. W. [S]H.' the 'onlie begetter', i.e., the sole author, of the sonnets, and the dedication is advertising the authenticity of the poems.

- William Hall, a printer who had worked with Thorpe on other publications. According to this theory, the dedication is simply Thorpe's tribute to his colleague and has nothing to do with Shakespeare. This theory, originated by Sir Sidney Lee in his A Life of William Shakespeare (1898), was continued by Colonel B.R. Ward in his The Mystery of Mr. W.H. (1923), and has been endorsed recently by Brian Vickers, who notes Thorpe uses such 'visual puns' elsewhere.[10] Supporters of this theory point out that "ALL" following "MR. W. H." spells "MR. W. HALL" with the deletion of a period. Using his initials W.H., Hall had edited a collection of the poems of Robert Southwell that was printed by George Eld, the same printer for the 1609 Sonnets.[11] There is also documentary evidence of one William Hall of Hackney who signed himself 'WH' three years earlier, but it is uncertain if this was the printer.

- Sir William Harvey, Southampton's stepfather. This theory assumes that the fair youth and Mr. W.H. are separate people, and that Southampton is the fair youth. Harvey would be the "begetter" of the Sonnets in the sense that it would be he who provided them to the publisher, after the death of Southampton's mother removed a obstacle to publication. The reservations about the use of "Mr" did not apply in the case of a knight.[7][12]

- William Himself (i.e. Shakespeare). This theory was proposed by the German scholar D. Barnstorff, but has not found much support.[7]

- William Haughton, a contemporary dramatist.[13][14]

- William Hart, Shakespeare's nephew and male heir. Proposed by Richard Farmer, but Hart was nine years of age at the time of publication, and this suggestion is regarded as unlikely.[15]

- Who He. In his 2002 Oxford Shakespeare edition of the sonnets, Colin Burrow argues that the dedication is deliberately mysterious and ambiguous, possibly standing for "Who He", a conceit also used in a contemporary pamphlet. He suggests that it might have been created by Thorpe simply to encourage speculation and discussion (and hence, sales of the text).[16]

- Willie Hughes. The 18th century scholar Thomas Tyrwhitt first proposed the theory that the Mr. W.H. (and the Fair Youth) was one "William Hughes", based on presumed puns on the name in the sonnets. The argument was repeated in Edmund Malone's 1790 edition of the sonnets. The most famous exposition of the theory is in Oscar Wilde's short story "The Portrait of Mr. W.H.", in which Wilde, or rather the story's narrator, describes the puns on "will" and "hues" in the sonnets, (notably Sonnet 20 among others), and argues that they were written to a seductive young actor named Willie Hughes who played female roles in Shakespeare's plays. There is no evidence for the existence of any such person.

Structure

The sonnets are almost all constructed from three four-line stanzas (called quatrains) and a final couplet composed in iambic pentameter[17] (a meter used extensively in Shakespeare's plays) with the rhyme scheme abab cdcd efef gg (this form is now known as the Shakespearean sonnet). The only exceptions are Sonnets 99, 126, and 145. Number 99 has fifteen lines. Number 126 consists of six couplets, and two blank lines marked with italic brackets; 145 is in iambic tetrameters, not pentameters. Often, the beginning of the third quatrain marks the volta ("turn"), or the line in which the mood of the poem shifts, and the poet expresses a revelation or epiphany.

There is another variation on the standard English structure, found for example in sonnet 29. The normal rhyme scheme is changed by repeating the b of quatrain one in quatrain three where the f should be. This leaves the sonnet distinct between both Shakespearean and Spenserian styles.

| “ | When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes I all alone beweep my outcast state, |

” |

Whether the author intended to step over the boundaries of the standard rhyme scheme will always be in question. Some, like Sir Denis Bray, find the repetition of the words and rhymes to be a "serious technical blemish",[18] while others, like Kenneth Muir, think "the double use of 'state' as a rhyme may be justified, in order to bring out the stark contrast between the Poet's apparently outcast state and the state of joy described in the third quatrain."[19] Given that this is the only sonnet in the collection that follows this pattern, its hard to say if it was purposely done. But most of the poets at the time were well educated; "schooled to be sensitive to variations in sounds and word order that strike us today as remarkably, perhaps even excessively, subtle." [20] Shakespeare must have been well aware of this subtle change to the firm structure of the English sonnets.

Characters

Some scholars of the sonnets refer to these characters as the Fair Youth, the Rival Poet, and the Dark Lady, and claim that the speaker expresses admiration for the Fair Youth's beauty, and later has an affair with the Dark Lady. It is not known whether the poems and their characters are fiction or autobiographical. If they are autobiographical, the identities of the characters are open to debate. Various scholars, most notably A. L. Rowse, have attempted to identify the characters with historical individuals.

Fair Youth

_cropped.png)

The 'Fair Youth' is an unnamed young man to whom sonnets 1-126 are addressed. The poet writes of the young man in romantic and loving language, a fact which has led several commentators to suggest a homosexual relationship between them, while others read it as platonic love, or even as the love of a father for his son.

The earliest poems in the collection do not imply a close personal relationship; instead, they recommend the benefits of marriage and children. With the famous sonnet 18 ("Shall I compare thee to a summer's day") the tone changes dramatically towards romantic intimacy. Sonnet 20 explicitly laments that the young man is not a woman. Most of the subsequent sonnets describe the ups and downs of the relationship, culminating with an affair between the poet and the Dark Lady. The relationship seems to end when the Fair Youth succumbs to the Lady's charms.

There have been many attempts to identify the Friend. Shakespeare's one-time patron, the Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton is the most commonly suggested candidate, although Shakespeare's later patron, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, has recently become popular [1]. Both claims have much to do with the dedication of the sonnets to 'Mr. W.H.', "the only begetter of these ensuing sonnets": the initials could apply to either Earl. However, while Shakespeare's language often seems to imply that the 'friend' is of higher social status than himself, this may not be the case. The apparent references to the poet's inferiority may simply be part of the rhetoric of romantic submission. An alternative theory, most famously espoused by Oscar Wilde's short story 'The Portrait of Mr. W.H.' notes a series of puns that may suggest the sonnets are written to a boy actor called William Hughes; however, Wilde's story acknowledges that there is no evidence for such a person's existence. Samuel Butler believed that the friend was a seaman, and recently Joseph Pequigney ('Such Is My love') an unknown commoner.

The Dark Lady

She is also described as dark-haired.

William Wordsworth was unimpressed by these sonnets. He wrote that:

These sonnets, beginning at 127, to his Mistress, are worse than a puzzle-peg. They are abominably harsh, obscure & worthless. The others are for the most part much better, have many fine lines, very fine lines & passages. They are also in many places warm with passion. Their chief faults, and heavy ones they are, are sameness, tediousness, quaintness, & elaborate obscurity.

The Rival Poet

The Rival Poet's identity has always remained a mystery, though there is a general consensus that the two most likely candidates are Christopher Marlowe and George Chapman. However, there is no hard evidence that the character had a real-life counterpart. The Poet sees the Rival as competition for fame and patronage. The sonnets most commonly identified as The Rival Poet group exist within the Fair Youth series in sonnets 78–86.[21]

Themes

One interpretation is that Shakespeare's Sonnets are in part a pastiche or parody of the three centuries-long tradition of Petrarchan love sonnets; in them, Shakespeare consciously inverts conventional gender roles as delineated in Petrarchan sonnets to create a more complex and potentially troubling depiction of human love.[22] Shakespeare also violated many sonnet rules which had been strictly obeyed by his fellow poets: he plays with gender roles (20), he speaks on human evils that do not have to do with love (66), he comments on political events (124), he makes fun of love (128), he speaks openly about sex (129), he parodies beauty (130), and even introduces witty pornography (151).

Legacy

Coming as they do at the end of conventional Petrarchan sonneteering, Shakespeare's sonnets can also be seen as a prototype, or even the beginning, of a new kind of 'modern' love poetry. During the eighteenth century, their reputation in England was relatively low; as late as 1805, The Critical Review could still credit John Milton with the perfection of the English sonnet. As part of the renewed interest in Shakespeare's original work that accompanied Romanticism, the sonnets rose steadily in reputation during the nineteenth century.[23]

The outstanding cross-cultural importance and influence of the sonnets is demonstrated by the large number of translations that have been made of them. To date in the German-speaking countries alone, there have been 70 complete translations since 1784. There is no major written language into which the sonnets have not been translated, including Latin,[24] Turkish, Japanese, Esperanto,[25] and even Klingon.[26]

The sonnets are often referenced in popular culture. For example in a 2007 episode of Doctor Who, entitled The Shakespeare Code, Shakespeare began a good-bye to Martha Jones in the form of Sonnet 18, referring to her as his dark lady. This is intended to indicate that Martha is the famed Dark Lady from these sonnets.

Modern editions

Legally, the sonnets (like all of Shakespeare's work) are in the public domain. This has prompted them to be reprinted in many editions.

- Martin Seymour-Smith (1963) Shakespeare's Sonnets (Oxford, Heinemann Educational)

- Stephen Booth (1977) Shakespeare's Sonnets (Yale)

- W G Ingram and Theodore Redpath (1978) Shakespeare's Sonnets, 2nd Edition

- John Kerrigan (1986) The Sonnets and a Lover's Complaint (Penguin)

- Katherine Duncan-Jones (1997) Shakespeare's Sonnets (Arden Edition, Third Series)

- Helen Vendler (1997) The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Harvard University Press

- Colin Burrow (2002) The Complete Sonnets and Poems (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

- G. Blakemore Evans (1996) The Sonnets (Cambridge UP)

International Translations

- Manfred Pfister, Jürgen Gutsch (ed) (2009) William Shakespeare's Sonnets - For the First Time Globally Reprinted - A Quatercentenary Anthology 1609-2009 (with a DVD) (Dozwil, Edition SIGNAThUR)

This anthology brings together translations in languages from all over the world, including many of the major as well as minor languages. Around seventy-five contributors wrote pieces on the translations of Shakespeare's sonnets, and on the accompanying DVD one hears these translations read aloud. Manfred Pfister and Jürgen Gutsch included translations to dialects and minor languages, e.g. Sign Language, Basque, Maori, Pennsylvania Dutch and Sorbian, and even some translations to artificial languages such as Klingon, but of course included translations to major languages such as Russian, German, French and Italian. Chapters were written by recognised scholars and/or translators in a particular language, e.g. the Afrikaans section was written by Hennie van Coller and Burgert Senekal, while the Yiddish section was written by Elvira Groezinger, making the anthology a credible academic resource.

See also

- George Bernard Shaw's The Dark Lady of the Sonnets

- Sonnet 1 through Sonnet 154

Pop culture

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 is referenced in the films Venus, Dead Poets Society, Shakespeare in Love, Clueless, and the 2007 Doctor Who episode "The Shakespeare Code" (in which Shakespeare addresses it to Martha Jones, calling her "my Dark Lady"). It also gave names to the band The Darling Buds and the books and television series The Darling Buds of May and Summer's Lease.

Ngaio Marsh's book Death at the Dolphin features a playwright, Peregrine Jay, who portrays a sexual relationship between the Dark Lady and Shakespeare in his latest work.

The Sonnet Lover, a novel by Carol Goodman, is constructed around the possibility that the Dark Lady was, in fact, a woman of Tuscany, and herself a creator of fine sonnets.

Shakespeare's Sonnet 29 is read as voice-over in the episode "Siege" of the 1987 tv series Beauty and the Beast by Vincent, played by Ron Perlman, who have left the book of sonnets as a gift to Catherine, played by Linda Hamilton.

Daryl Mitchell's character, Mr. Morgan, quotes the first four lines of Sonnet 141 in the movie 10 Things I Hate About You.

In 2009, Rufus Wainwright set twenty-five of Shakespeare's Sonnets to music (including 10, 20, 29, and 43) for a play from Robert Wilson and Berlin ensemble. Three of these will be released in his 2010 album, All Days Are Nights: Songs for Lulu.

Shakespeare's Sonnet 73 has been turned into a song by the singer/songwriter Natalie Merchant.

Kate Winslet's character, Marianne Dashwood, quotes from part of Shakespeare's Sonnet 116 in the 1995 film, Sense and Sensibility.[27] The quote is first introduced to show the similarity between Marianne Dashwood's character and that of her first love, Mr. Willoughby. It is later used to point up Willoughby's inconstancy.

Shakespeare's Sonnet 130 is taught in an episode of "My So-Called Life," and even the laconic Jordan Catalano gets involved in class, to acknowledge that, yes, the speaker is in love with the girl he is describing, even though she is imperfect.

Shakespeare's Sonnet 94 is incorporated into the song "If There Was Love" written by Pet Shop Boys and recorded by Liza Minnelli for her 1989 album Results.

Notes

- ↑ Stanley Wells and Michael Dobson, eds., The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 439.

- ↑ Foster, Donald. "Master W.H., R.I.P." PMLA 102 (1987) 42–54, 42.

- ↑ Burrow, Colin (2002). Complete Sonnets and Poems. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 019818431X.

- ↑ Foster 1984, 43.

- ↑ Vickers, Brian (2007). Shakespeare, A lover's complaint, and John Davies of Hereford. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0521859123.

- ↑ Burrow 2002, 380.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Schoenbaum, Samuel (1977). William Shakespeare, a compact documentary life (1 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 270–271. ISBN 01981257555.

- ↑ Foster, 1987.

- ↑ Bate, Jonathan. The Genius of Shakespeare (1998) 61-62.

- ↑ Vickers, 2007,8

- ↑ Collins, John Churton. Ephemera Critica. Westminster, Constable and Co., 1902; p. 216.

- ↑ Appleby, John C (January 2008). "Hervey, William, Baron Hervey of Kidbrooke and Baron Hervey of Ross (d. 1642)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Berryman, John (2001). Haffenden, John. ed. Berryman's Shakespeare: essays, letters and other writings. London: Tauris Parke. p. xxxvi. ISBN 9781860646430.

- ↑ Neil, Samuel (27 April 1867). Athenæum (London): 552.

- ↑ Neil, Samuel (1863). Shakespere: a critical biography. London: Houlston and Wright. pp. 105–106. OCLC 77866350.

- ↑ Colin Burrow, ed. The Complete Sonnets and Poems (Oxford UP, 2002), p. 98; 102-3.

- ↑ A metre in poetry with five iambic metrical feet, which stems from the Italian word endecasillabo, for a line composed of five beats with an anacrusis, an upbeat or unstressed syllable at the beginning of a line which is no part of the first foot.

- ↑ Bray, Sir Denis. The Original Order of Shakespeare's Sonnets. (Brooklyn: Haskell House, 1977) p. 36

- ↑ Muir, Kenneth. Shakespeare's Sonnets. (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1979) p. 57

- ↑ McGuire, Philip C. Shakespeare's Non-Shakespearean Sonnets. Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 3 (Autumn, 1987) p. 304-319; 306

- ↑ OxfordJournals.org

- ↑ Stapleton, M. L. "Shakespeare's Man Right Fair as Sonnet Lady." Texas Studies in Literature and Language 46 (2004): 272

- ↑ Sanderlin, George (June 1939). "The Repute of Shakespeare's Sonnets in the Early Nineteenth Century". Modern Language Notes (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 54 (6): 462–466. doi:10.2307/2910858. http://jstor.org/stable/2910858.

- ↑ Shakespeare's Sonnets in Latin, translated by Alfred Thomas Barton, newly edited by Ludwig Bernays, Edition Signathur, Dozwil/CH 2006

- ↑ Shakespeare: La sonetoj (sonnets in Esperanto), Translated by William Auld, Edistudio, Edistudio Homepage, verified 2008/02/03

- ↑ Selection of Shakespearean Sonnets, Translated by Nick Nicholas, verified 2005/02/27

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0114388/trivia

External links

- Historical background to Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Sonnets – Compare two sonnets side-by-side, see all of them together on one page, or view a range of sonnets (from Open Source Shakespeare)

- The Sonnets – Full text and commentary.

- The Sonnets – Plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg

- Shakepeare's Sonnets Overview of each in contemporary English

- Free audiobook from LibriVox

- Complete sonnets of William Shakespeare – Listed by number and first line.

- Gerald Massey - 'The Secret Drama of Shakspeare's Sonnets (1888 edition)

- Discussion of the identification of Emily Lanier as the Dark Lady

- Shakespeare Sonnet Shake-Up "Remix" Shakespeare's sonnets

- shakespeareintune.com all the 154 Sonnets are here recited with a musical introduction.

- Online, free, self-referential concordance to the Sonnets

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Full list of sonnets

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||