Skull and Bones

Skull and Bones is a secret society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The society's alumni organization, which owns the society's real property and oversees the organization, is the Russell Trust Association, named for General William Huntington Russell,[1] who co-founded Skull and Bones with classmate Alphonso Taft. The Russell Trust was founded by Russell and Daniel Coit Gilman, member of Skull and Bones and later one of the earliest Presidents of the University of California and also the first President of Johns Hopkins University, and later the founding President of the Carnegie Institution. The society is known informally as "Bones", and members are known as "Bonesmen".[2]

During the senior year, each Skull and Bones class meets every Thursday and Sunday night.[3]

President George H. W. Bush, his son, President George W. Bush, and the latter's 2004 Presidential opponent, Senator John Kerry, are members of Skull and Bones.[4][5]

"Conspiracy theories about the Skull & Bones Society are almost as old as the society itself," Time magazine has reported. "The group has been blamed for everything from the creation of the nuclear bomb to the Kennedy assassination."[6]

Contents |

History

Skull and Bones was founded in 1832 after a dispute among Yale's debating societies, Linonia, Brothers in Unity, and Calliope, over that season's Phi Beta Kappa awards; its original name was "the Order of Skull and Bones."[7][8]

The only chapter of Skull and Bones created outside Yale was a chapter at Wesleyan University in 1870. That chapter, the Beta of Skull & Bones, became independent in 1872 in a dispute over control over creating additional chapters; the Beta Chapter reconstituted itself as Theta Nu Epsilon.[9][10]

Skull & Bones operates as a peer society with Scroll and Key and Wolf's Head.

Skull and Bones owns a campground island in the St. Lawrence River in upstate New York named Deer Island. "'The 40 acre retreat is intended to give Bonesmen an opportunity to 'get together and rekindle old friendships.' A century ago the island sported tennis courts and its softball fields were surrounded by rhubarb plants and gooseberry bushes. Catboats waited on the lake. Stewards catered elegant meals. Although each new Skull and Bones member still visits Deer Island, the place leaves something to be desired. 'Now it is just a bunch of burned-out stone buildings,' a patriarch sighs. 'It's basically ruins.' Another Bonesman says that to call the island 'rustic' would be to glorify it. 'It's a dump, but it's beautiful.'"[11]

Yale became coeducational in 1969, but Skull & Bones remained all-male at the behest of the Russell Trust Association. The Class of 1991 disregarded the Trust and tapped seven female members for membership in the next year's class.[12] The Trust responded by changing the locks on the "Tomb"; the Bonesmen had to meet at the building of Manuscript Society.[12] A mail-in vote by living members decided 368-320 to permit going co-ed, but a group of alumni led by William F. Buckley obtained a temporary restraining order to block the move, arguing that a formal change in bylaws was needed.[12][13] Other alumni, such as John Kerry, spoke out in favor of admitting women, and the dispute even ended up on The New York Times editorial page.[12][14] A second vote of alumni in October 1991 agreed to accept the Class of 1992, and the lawsuit was dropped.[12][15] Wolf's Head Society was the last all-male society at Yale.[16]

Membership selection

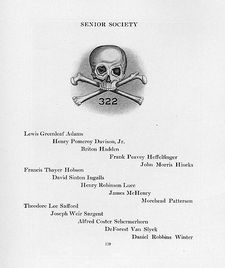

Skull and Bones selects new members every spring as part of Yale University's "Tap Day"; the most recent Tap Day was held on April 15, 2010.[17] Every year, Skull and Bones selects fifteen men and women of the junior class to join the society. Skull and Bones traditionally "tapped" those that it viewed as campus leaders and other notable figures for its membership.[18] Traditionally, groups such as the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, Yale Political Union, and Yale Daily News were well represented. In addition, captains of various athletics teams are also considered. Bones began tapping Jewish students in the early fifties and African-Americans in 1949.[19] Like its counterparts, Bones has diversified further its membership, typically with leaders of undergraduate ethnic and racial affinity groups, since the 1980s.

Skull and Bones has developed a reputation with some as having a membership that is heavily tilted towards the "Power Elite".[20] Barack Obama's economic adviser Austan Goolsbee was initiated into the club in 1991, the same year the club elected to let women into the society.[21]

Lore

The first extended description of Skull and Bones, published in 1871 by Lyman Bagg in his book Four Years at Yale, noted that "the mystery now attending its existence forms the one great enigma which college gossip never tires of discussing."[22] Brooks Mather Kelley attributed the secrecy of Yale senior societies to the fact that underclassmen members of freshman, sophomore, and junior class societies remained on campus following their membership, while seniors naturally left.[23]

One legend is that 322 in the emblem of the society stands for "founded in '32, 2nd corps", referring to a first Corps in an unknown German university.[24][25] Others suggest that 322 refers to the death of Demosthenes and that documents in the society hall have purportedly been found dated to "Anno-Demostheni".[26]

There is an ongoing rumor that there is some form whereby new members recite to the society their sexual history, and although there has been no corroboration of this by any reliable source, the rumor lives on.[27]

Members are assigned nicknames. "Long Devil" is assigned to the tallest member; "Boaz" goes to any member who is a varsity football captain. Many of the chosen names are drawn from literature ("Hamlet", "Uncle Remus"), from religion and from myth. The banker Lewis Lapham passed on his nickname, "Sancho Panza", to the political adviser Tex McCrary. Averell Harriman was "Thor", Henry Luce was "Baal", McGeorge Bundy was "Odin", and George H. W. Bush was "Magog".[11]

Alleged stolen artifacts

Skull and Bones has a reputation for stealing keepsakes, from other Yale societies or from campus buildings; society members reportedly call the practice "crooking" and strive to outdo each other's "crooks."[28]

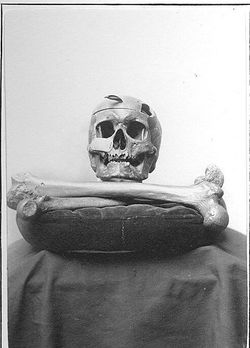

The society has been accused of possessing the stolen skulls of Martin Van Buren, Geronimo, and Pancho Villa, but this has never been proven.[29][30][31]

Geronimo

Skull and Bones members supposedly stole the bones of Geronimo from Fort Sill, Oklahoma during World War I. In 1986, former San Carlos Apache Chairman Ned Anderson received an anonymous letter with a photograph and a copy of a log book claiming that Skull & Bones held the skull. He met with Skull & Bones officials about the rumor; the group's attorney, Endicott P. Davidson, denied that the group held the skull, and said that the 1918 ledger saying otherwise was a hoax.[32] The group offered Anderson a glass case with a skull of a ten-year-old boy, but Anderson refused it.[33] In 2006, Marc Wortman discovered a 1918 letter[34] from Skull & Bones member Winter Mead to F. Trubee Davison that claimed the theft was "exhumed" from Fort Sill by the club and was "safe" in the club's headquarters.[35]

In 2009, Ramsey Clark filed a lawsuit on behalf of people claiming to be Geronimo's descendants, against, among others, Barack Obama, Robert Gates, and Skull and Bones, asking for the return of Geronimo's bones.[32] An article in The New York Times states that Clark "acknowledged he had no hard proof that the story was true."[36] Alexandra Robbins says this is one of the more plausible items said to be in the organization's Tomb.[37] But Cameron University history professor David H. Miller notes that Geronimo's grave was unmarked at the time.[35] Investigations ranging from Cecil Adams to Kitty Kelley have rejected the story.[38][39] A Fort Sill spokesman told Adams, "There is no evidence to indicate the bones are anywhere but in the grave site."[38] Jeff Houser, chairman of the Fort Sill Apache tribe of Oklahoma, also calls the story a hoax.[33]

The 1918 letter “ adds to the seriousness of the belief [that the theft took place], certainly,” says Judith Schiff, the chief research archivist at Sterling Memorial Library, who has written extensively on Yale history. “It has a very strong likelihood of being true, since it was written so close to the time.” She points out that Members of a secret society were required to be honest with each other about its affairs. The yearbook entries for Haffner, Mead, and Davison say that they were all Bonesmen. (The membership of the societies was routinely published in newspapers and yearbooks until the 1970s.) Haffner’s entry says that he was at the artillery school at Fort Sill some time between August 1917 and July 1918.[28]

Pancho Villa

Pancho Villa's skull was indeed stolen shortly after his death.[29] While Robbins originally wrote in her book that the Bonesmen had the skull, she has since retracted the claim, saying that the story that the Bonesmen paid $25,000 for it in the 1920s is implausible.[29] Writer Mark Singer, a Yale graduate, also rejects the story in a New Yorker article about the myth.[40]

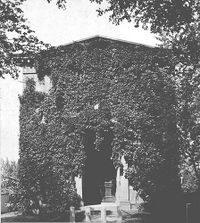

Skull & Bones Hall

The Skull & Bones Hall is otherwise known as the "Tomb". The architectural attribution of the original hall is in dispute. The architect was possibly Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892) or Henry Austin (1804–1891). Architectural historian Patrick Pinnell includes an in-depth discussion of the dispute over the identity of the original architect in his 1999 history of Yale's campus.[41]

The building was built in three phases: in 1856 the first wing was built, in 1903 the second wing, and in 1911, Davis-designed Neo-Gothic towers from a previous building were added at the rear garden. The front and side facades are of Portland brownstone and in an Egypto-Doric style.

The 1911 additions of towers in the rear created a small enclosed courtyard in the rear of the building, designed by Evarts Tracy and Edgerton Swartwout, Tracy and Swartwout, New York.[42] Evarts was not a Bonesman, but his paternal grandmother Martha Sherman Evarts and maternal grandmother Mary Evarts were the sisters of William Maxwell Evarts (S&B 1837). Pinnell speculates whether the re-use of the Davis towers in 1911 was evidence suggesting that Davis did the original building; conversely, Austin was responsible for the architecturally similar brownstone Egyptian Revival gates, built 1845, of the Grove Street Cemetery, to the north of campus. Also discussed by Pinnell is the "tomb's" aesthetic place in relation to its neighbors, including the Yale University Art Gallery.[43] New Hampshire landscape architects Saucier & Flynn designed the wrought-iron fence that currently surrounds a portion of the complex in the late 1990s.[44]

Bonesmen

Judy Schiff, Chief Archivist at the Yale University Library, has written: "The names of (S&B's) members weren't kept secret, that was an innovation of the 1970s, but its meetings and practices were. The secrecy seems to have attracted fascination and curiosity from the start."

While resourceful researchers could assemble member data from these original sources, in 1985 an anonymous source leaked rosters to an economic historian, Antony C. Sutton, who wrote a book on the group titled America's Secret Establishment: An Introduction to the Order of Skull & Bones.[45] This leaked 1985 data was kept privately for over 15 years, as Sutton feared that the photocopied pages could somehow identify the member who leaked it. The information was finally reformatted as an appendix in the book Fleshing out Skull and Bones, a compilation edited by Kris Millegan, published in 2003.

Among prominent deceased alumni were President William Howard Taft, Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart,[46] "mother of the Central Intelligence Agency", and United States Secretary of Defense, Robert A. Lovett, who directed the Korean War. Some prominent living members are Senator David L. Boren,[15], Steve Schwarzman, Chairman of the Blackstone Group, and Austan Goolsbee, the chief economist of a federal panel, the President's Economic Recovery Advisory Board.[47]

In popular culture

Skull and Bones' place in popular culture is significant, since, although it is a "secret society," it is probably the best known college secret society in America, as can be seen from the recurring references to it in all kinds of media. Skull and Bones has featured from time to time in the Doonesbury comic strips by Garry Trudeau; especially in 1980 and December 1988, with reference to George H. W. Bush, and again at the time that the society went co-ed.[48] In The Simpsons, Montgomery Burns is both a Yalie and a Bonesman. The 2000 film The Skulls concerns a highly elaborate secret society with clear parallels to Skull and Bones at a university beginning with a "Y";[49] A portrayal of Bones also played a substantial role in Robert De Niro's 2006 film The Good Shepherd, about the Central Intelligence Agency.[50]

References

- ↑ The New York Times, "Change In Skull And Bones. Famous Yale Society Doubles Size of Its House — Addition a Duplicate of Old Building", published September 13, 1903.

- ↑ Stevens, Albert C. (1907). Cyclopedia of Fraternities: A Compilation of Existing Authentic Information and the Results of Original Investigation as to the Origin, Derivation, Founders, Development, Aims, Emblems, Character, and Personnel of More Than Six Hundred Secret Societies in the United States. E. B. Treat and Company. p. 338.

- ↑ http://www.yaledailynews.com/articles/view/17253

- ↑ George W. Bush, A Charge to Keep, (1999) ISBN 0-688-17441-8.

- ↑ washingtonpost.com: Bush, Kerry Share Tippy-Top Secret.

- ↑ Time.com: A Brief History Of The Skull & Bones Society

- ↑ The New York Times, "Change In Skull And Bones. Famous Yale Society Doubles Size of Its House — Addition a Duplicate of Old Building," published September 13, 1903.

- ↑ Niarchos, Nicolas; Victor Zapana (December 5, 2008). "Yale's secret social fabric". Yale Daily News. http://www.yaledailynews.com/articles/view/26882. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ Wesleyan Argus, History of Theta Nu Epsilon and connection to Skull & Bones, February 7, 1992, p. 6.

- ↑ The Wesleyan Review, May 1990.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Alexandra Robbins, The Atlantic Monthly May, 2000.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Andrew Cedotal, Rattling those dry bones, Yale Daily News, April 18, 2006.

- ↑ "Yale Alumni Block Women in Secret Club". New York Times. September 6, 1991. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE6DE1738F935A3575AC0A967958260. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ Semple, Robert B., Jr. (April 18, 1991). "High Noon on High Street". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CEFD7153CF93BA25757C0A967958260&sec=&spon=. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Hevesi, Dennis (October 26, 1991). "Shh! Yale's Skull and Bones Admits Women". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE5DB1130F935A15753C1A967958260&scp=1&sq=skull%20bones%20women&st=cse. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ Phelps Association Membership Directory, 2006.

- ↑ http://www.yaledailynews.com/articles/view/28799

- ↑ http://www.conspiracyarchive.com/NWO/Tombs_and_Taps.htm

- ↑ http://www.theforbiddenknowledge.com/hardtruth/more_skull_and_bones.htm

- ↑ "Skull And Bones". CBS News. October 2, 2003. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/10/02/60minutes/main576332.shtml.

- ↑ http://www.yaledailynews.com/articles/view/21789

- ↑ Yale Alumni Magazine: Old Yale at www.yalealumnimagazine.com.

- ↑ Yale: A History, Brooks Mather Kelley, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, Ltd.), 1974.

- ↑ Robbins, Alexandra. Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Back Bay Books, 2003.

- ↑ and bones&q1=&q2=&qc1=&qc2=&qf1=&qf2=&qn=&qo=&qm=&qs=&sid=&qx= Yale University Archives

- ↑ Stevens, Albert C. (1907). Cyclopedia of Fraternities: A Compilation of Existing Authentic Information and the Results of Original Investigation as to the Origin, Derivation, Founders, Development, Aims, Emblems, Character, and Personnel of More Than Six Hundred Secret Societies in the United States. E. B. Treat and Company. p. 340.

- ↑ http://www.yaleherald.com/archive/frosh/1998/blue/secret.html

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Lassila;Branch (2006). "Whose skull and bones?". Yale Alumni Magazine: 20–22. http://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/2006_05/images/Yale_Alumn_Magazine.pdf

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Greenburg, Zach O. (January 23, 2004). "Bones may have Pancho Villa skull". Yale Daily Herald. http://google.yale.edu/search?q=cache:uIbi9_wDw5sJ:www.yaleherald.com/article.php%3FArticle%3D2801&access=p&output=xml_no_dtd&ie=UTF-8&client=bluesite_frontend&site=Yale_University&proxystylesheet=bluesite_frontend&oe=ISO-8859-1. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Citro, Joseph A. (2005). Weird New England (illustrated ed.). Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.. pp. 270–71. ISBN 1402733305.

- ↑ Bones may have Pancho Villa Skull by Zach Greenburg, The Yale Herald, 2004.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Daniels, Bruce (February 27, 2009). "Geronimo Lawsuit Sparks Family Feud". Albuquerque Journal. http://www.abqjournal.com/abqnews/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=10846:635am-geronimo-died-100-years-ago-today&catid=1:latest&Itemid=39. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Pember, Mary Annette (July 9, 2007). "Tomb Raiders". Diverse Issues in Higher Education. http://www.diverseeducation.com/artman/publish/article_8184.shtml. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ http://images.library.yale.edu/madid/oneItem.aspx?id=1777202&q=skull%20and%20bones&q1=&q2=&qc1=&qc2=&qf1=&qf2=&qn=&qo=&qm=15&qs=16&sid=&qx=

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Lassila, Kathrin Day; Mark Alden Branch (May/June 2006). "Whose Skull and Bones?". Yale Alumni Magazine. http://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/2006_05/notebook.html. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ Geronimo's Heirs Sue Secret Yale Society Over His Skull

- ↑ Geronimo's kin sue Skull and Bones over remains

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/2623/is-geronimos-skull-residing-at-yales-skull-and-bones

- ↑ Kelley, Kitty (2004). The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty. Doubleday. pp. 17–20.

- ↑ Singer, Mark (November 27, 1989). "La Cabeza de Villa". New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1989/11/27/1989_11_27_108_TNY_CARDS_000356240. Retrieved 2009-03-08. "It is a simple fact that Frank Brophy graduated from Yale College but was never a member of Skull and Bones... Whatever hung on Brophy's wall would therefore not have been 'a plaque of the Skull and Bones Society.' This strongly implies, of course, that if Frank Brophy (who died in 1978) told Ben Williams (who died in 1985) that he and four Bones accomplices had paid twenty-five thousand dollars for Pancho Villa's cranium his object was to embroider an anecdote that sounded to him more colorful than truthful."

- ↑ Yale's Lost Landmarks at www.yalealumnimagazine.com.

- ↑ "Yale University" 1999 Princeton Architectural Press, ISBN 1-56898-167-8 [1]

- ↑ "Yale University" 1999 Princeton Architectural Press, p. 42, ISBN 1-56898-167-8 [2]

- ↑ Fence information

- ↑ http://www.scribd.com/doc/4219811/Americas-Secret-Establishment-An-Introduction-to-Skull-and-Bones|Antony-C-Sutton

- ↑ Barron, James (July 25, 1991). "Male Fortress Falls at Yale: Bonesmen to Admit Women". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE6DE1139F936A15754C0A967958260&n=Top%2FReference%2FTimes%20Topics%2FOrganizations%2FY%2FYale%20University. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ "Goolsbee joins Obama econ. team". Yale Daily News. November 26, 2008. http://www.yaledailynews.com/articles/view/26705. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ Soper, Kerry (2008). Garry Trudeau: Doonesbury and the Aesthetics of Satire. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 25, 42. ISBN 1934110892.

- ↑ Dempsey, Rachel (September 25, 2007). "Alum's novels set in alterna-Yale". Yale Daily News. http://www.yaledailynews.com/articles/view/21492. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ Dempsey, Rachel (January 18, 2007). "Real Elis inspired fictional 'shepherd'". Yale Daily News. http://www.yaledailynews.com/articles/view/19447. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

Further reading

- Hodapp, Christopher; Alice Von Kannon (2008). Conspiracy Theories & Secret Societies For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0470184086.

- Robbins, Alexandra. Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Back Bay Books, 2003. ISBN 0-316-73561-2.

- Sutton, Antony C. America's Secret Establishment: An Introduction to the Order of Skull & Bones. Walterville, OR: Trine Day, 2003. ISBN 0-9720207-0-5.

- Tedford, Cody. Powerful Secrets. Hannover, 2008. ISBN 1-4241-9263-3.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||