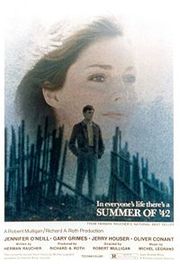

Summer of '42

| Summer of '42 | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Robert Mulligan |

| Produced by | Richard A. Roth |

| Written by | Herman Raucher |

| Starring | Jennifer O'Neill Gary Grimes |

| Music by | Michel Legrand |

| Cinematography | Robert Surtees |

| Editing by | Folmar Blangsted |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

| Release date(s) | April 9, 1971 |

| Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million |

Summer of '42 is a 1971 American "coming-of-age" drama film based on the memoirs of screenwriter Herman Raucher. It tells the story of Raucher as a boy, in his early teens on his 1942 summer vacation on Nantucket Island, off the coast of New England, who embarked on a one-sided romance with a woman, Dorothy, whose husband had gone off to fight in World War II. The film was directed by Robert Mulligan, and starred Gary Grimes as Hermie, Jerry Houser as his best friend Oscy, Oliver Conant as their nerdy young friend Benjie, Jennifer O'Neill as Hermie's mysterious love interest, and Katherine Allentuck and Christopher Norris as a pair of girls whom Hermie and Oscy attempt to seduce. Mulligan also has an uncredited role as the voice of the adult Hermie. Academy Award-winning actress Maureen Stapleton (Allentuck's real life mother) also appears in a small, uncredited voice role (calling after Hermie as he leaves the house in an early scene).

Raucher's novelization of his screenplay was released prior to the film's release and became a runaway bestseller, to the point that audiences lost sight of the fact that the book was based on the film and not vice-versa. Though a pop culture phenomenon in the first half of the 1970s, the novelization went out of print and slipped into obscurity throughout the next two decades until a Broadway adaptation in 2001 brought it back into the public light and prompted Barnes & Noble to acquire the publishing rights to the book. The next year, the film received a digitally remastered DVD release from Warner Bros. Today, the book remains in print.

Contents |

Plot

The film opens with a series of grainy, color-warped still photographs appearing over melancholy piano music, representing the abstract memories of the unseen Herman Raucher, now a middle-aged man. After the stills finish, we hear Raucher (Robert Mulligan in voiceover) recalling the summer he spent on the island in 1942. The film flashes back to a day that then 15-year-old "Hermie" (Gary Grimes) and his friends – jock Oscy (Jerry Houser) and introverted nerd Benjie (Oliver Conant) – spent running and playing on the beach. While goofing off, the three boys spot a young soldier carrying his new bride (Jennifer O'Neill) into a house on the beach. The boys are all struck by her beauty, especially Hermie, who finds himself unable to get her out of his mind.

They continue spending their afternoons on the beach where, in the midst of scantily-clad teenage girls, their thoughts invariably turn to sex. All of them are virgins. Oscy is obsessed with the act of sex, while Hermie finds himself developing genuine romantic interest in the young bride, whose husband he spots leaving the island on a military transport boat one morning. Later that day, Hermie finds her trying to carry numerous bags of groceries by herself, and helps her get them back to her house. The two strike up a friendship and he agrees to return in the future to help her out with chores.

Meanwhile, Oscy and Hermie, thanks to a sex manual discovered by Benjie, become convinced they now know everything necessary to lose their virginity. Led by Oscy, they put this to the test by going to the island film house and picking up a trio of high-school girls. Oscy stakes out the most attractive one, Miriam (Christopher Norris), for himself, "giving" Hermie her wallflower friend, Aggie (Katherine Allentuck) and leaving Benjie with Gloria, a heavyset girl with braces. Frightened by the immediacy of sex, Benjie runs off, and is not seen by Hermie or Oscy again. Gloria, thinking that her appearance repulsed Benjie, likewise walks away. Hermie and Oscy spend the entirety of the evening's film (Now, Voyager - which wasn't actually released until later in 1942) attempting to "put the moves" on Miriam and Aggie. Oscy aggressively but fruitlessly pursues Miriam, although he soon learns that her doings are well-known on the island, and she is simply playing hard to get. Hermie, meanwhile, finds himself succeeding with Aggie, who allows him to grope at length what he thinks is her breast; later, Oscy points out that he was in fact fondling her arm.

The following morning, Hermie helps the young bride move boxes into her attic, and when he turns down her offer of money, she thanks him with donuts and gives him a kiss on the forehead. Later, in preparation for a marshmallow roast on the beach with Aggie and Miriam, Hermie goes to the local drugstore. In a lengthy and painfully hilarious sequence he finally builds up the nerve to ask the pharmacist for condoms.

That night, Hermie roasts marshmallows with Aggie while Oscy succeeds in having sex with Miriam between the dunes. He is so successful that he eventually sneaks over to Hermie and Aggie and asks Hermie for more condoms. Confused as to what's happening, Aggie follows Oscy back, where she sees him having sex with Miriam and runs home crying. Hermie, too, sees the act, although he is more mesmerized than shocked.

The next day, Hermie comes across the young bride sitting outside her house, writing a letter to her husband. Hermie offers to come keep her company that night and she says she looks forward to seeing him, finally revealing that her name is Dorothy. An elated Hermie goes home and puts on a suit, saddle shoes, and a dress shirt, and heads back to Dorothy's house, running into Oscy on the way; Oscy relates that Miriam's appendix burst that morning and she's been rushed to the mainland.

Hermie, convinced he is at the brink of adulthood because of his relationship with Dorothy, brushes Oscy off. He heads over to Dorothy's house, which is eerily quiet. Going in uncertainly, he discovers an empty bottle of whiskey, several cigarette butts, and a telegram from the U.S. Government, with a time stamp of just an hour prior. Dorothy's husband is dead, his plane having been shot down over France. Dorothy comes out of her bedroom, crying, and Hermie, trying to get a grip on the painful situation, finally tells her "I'm sorry." The sense of empathy triggers her to channel on to Hermie some of her aching loneliness. She moves to the record player, turns on an album and invites Hermie to dance with her. Near the end of the song, Dorothy takes Hermie's hand. They kiss and embrace, tears on both their faces. Without speaking, and to the sound only of the waves, they move slowly to the bedroom, where she draws him into bed and gently makes love with him. Afterwards, withdrawing again into her world of hurt, Dorothy puts on her bathrobe and retires to the porch, leaving Hermie alone in her bedroom. He approaches her on the porch, where she can only quietly say "good night, Hermie." He leaves, his last image of Dorothy being of her leaning against the railing, as she smokes a cigarette and stares off into the night sky.

Hermie spends the night roaming the island in a state of shock. At dawn he meets Oscy and the two share a moment of reconciliation, with Oscy informing Hermie that Miriam will recover, but will be hospitalized until autumn. Oscy, in an uncharacteristic act of sensitivity, then lets Hermie be by himself, departing with the words, "Sometimes life is just one big pain in the ass."

Trying to sort out what has happened, Hermie goes back to Dorothy's house. He finds it abandoned, Dorothy having fled the island in the night. All that remains is an envelope tacked to her front door with Hermie's name on it. Inside is a note from Dorothy, saying that she hopes he understands that she must go back home as there is much to do. She assures Hermie that she will never forget him, and that he will find his own way of remembering what happened that night. Her note closes with the hope that Hermie may be spared the senseless tragedies of life.

In the film's final scene, Hermie, suddenly approaching manhood, is seen looking at Dorothy's old house and the ocean and remembering the day that he, Oscy, and Benjie first saw her. To bittersweet music, the adult Herman Raucher sadly recounts that in the ensuing years he has never seen Dorothy again or learned what became of her.

Factual basis

The film (and subsequent novel) were memoirs written by Herman Raucher; they detailed the events in his life over the course of the summer he spent on Nantucket Island in 1942 when he was fourteen years old.[1] Originally, the film was meant to be a tribute to his friend Oscar "Oscy" Seltzer, an Army medic killed in the Korean War.[1][2] Seltzer was shot dead on a battlefield in Korea whilst attending to a wounded man; this happened on Raucher's birthday, and consequently, Raucher has not celebrated a birthday since. During the course of writing the screenplay, Raucher came to the realization that despite growing up with Oscy and having bonded with him through their formative years, the two had never really had any meaningful conversations or gotten to know one another on a more personal level.[1]

Instead, Raucher decided to focus on the first major adult experience of his life, that of falling in love for the first time. The woman (named Dorothy, like her screen counterpart) was a fellow vacationer on the island whom Raucher had befriended one day when he helped her carry groceries home; he became a friend of her and her husband and helped her with chores after her husband was called to fight in World War II. Raucher went to bed with her one night when he came to visit her, arriving only minutes after she received notification of her husband's death.[1] The next morning, Raucher discovered that she had left the island, leaving behind a note for him (which is read at the end of the film and reproduced in the book). He never saw her again; his last "encounter" with her, recounted on an episode of The Mike Douglas Show, came after the film's release in 1971, when she was one of over a dozen women who wrote letters to Raucher claiming to be "his" Dorothy.[3] Raucher recognized the "real" Dorothy's handwriting, and she confirmed her identity by making references to certain events only she could have known about.[3] She told Raucher that she had lived for years with the guilt that she had potentially traumatized him and ruined his life. She told Raucher that she was glad he turned out all right, and that they had best not re-visit the past.[1][3]

In a 2002 interview, Raucher lamented never hearing from her again and expressed his hope that she was still alive.[1] Raucher's novelization of the screenplay, with the dedication, "To those I love, past and present," serves more as the tribute to Seltzer that he had intended the film to be, with the focus of the book being more on the two boys' relationship than Raucher's relationship with Dorothy. Consequently, the book also mentions Seltzer's death, which is omitted from the film adaptation.[4]

Production

Herman Raucher wrote the film script in the 1950s during his tenure as a television writer, but "couldn't give it away."[1] In the 1960s, he met Robert Mulligan, who had just finished directing To Kill a Mockingbird. Raucher showed Mulligan the script, and Mulligan took it to Warner Bros., knowing that the studio was looking for a follow up to Mockingbird. Mulligan argued the film could be shot for the relatively low price of a million dollars, and Warner approved it.[1] They had so little faith in the film becoming a box-office success, though, they shied from paying Raucher outright for the script, instead promising him ten percent of the gross.[1]

When casting for the role of Dorothy, Warner Bros. declined to audition any actresses younger than the age of thirty; Jennifer O'Neill's agent, who had developed a fondness for the script, convinced Warner Bros. to audition his client, who was only twenty-two at the time.[5] O'Neill auditioned for the role, albeit hesitantly, not wanting to perform any nude scenes; O'Neill ended up getting the role and Robert Mulligan agreed to find a way to make the film work without blatant nudity.[5]

Though the film took place on Nantucket, by the 1970s the island was too far modernized to be convincingly transformed to resemble a 1940s resort, so production was taken to Mendocino California, on the West Coast of the US.[1] Shooting took place over eight weeks, during which Jennifer O'Neill was sequestered from the three boys cast as "The Terrible Trio," in order to ensure that they didn't become close and ruin the sense of awkwardness and distance that their characters felt towards Dorothy. Production ran smoothly, finishing on schedule.[1]

After production, Warner Bros., still wary about the film only being a minor success, asked Raucher to adapt his script into a book.[1] Raucher wrote it in three weeks, and Warner Bros. released it prior to the film to build interest in the story.[1] The book quickly became a national bestseller, so that when trailers premiered in theatres, the film was billed as being "based on the national bestseller," despite the film having been completed first.[1][4] Ultimately, the book became one of the best selling novels of the first half of the 1970s, requiring 23 re-prints between 1971 and 1974 to keep up with customer demand.[4]

Soundtrack

The film's soundtrack consists almost entirely of compositions by Michel Legrand, many of which are variants upon "The Summer Knows", the film's theme. In addition to Legrand's scoring, the film also features the song "Hold Tight" by The Andrews Sisters and the theme from Now, Voyager. Due to this lack of songs, when the soundtrack was released, it contained not only the score to Summer, but also Legrand's composition "The Picasso Suite." In spite of this, many issues of the album are still labeled as exclusively being the soundtrack to Summer, while others contain the notation in small print on the album cover "Also contains 'The Picasso Suite'".

Reception and awards

The film became a blockbuster upon its release, grossing $25 million, making it the fourth-highest grossing film of 1971 and one of the most successful films in history, with an expense to profit ratio of 1:25;[6] beyond that, it is estimated video rentals and purchases in the United States since the 1980s have produced an additional $20.5 million.[7] On this point, Raucher says his ten percent of the gross, in addition to royalties from book sales, has "paid bills ever since."[1]

As well as being a commercial success, Summer of '42 also received rave critical reviews. It went on to be nominated for over a dozen awards, including Golden Globe Awards for "Best Motion Picture - Drama" and "Best Director", and the Academy Award for "Best Original Screenplay".[8] Ultimately, the film only won two awards, the "Best Score" Oscar" and the BAFTA Anthony Asquith Award for Film Music, both to Michel Legrand.[8] Still, it counted among its fans Stanley Kubrick, who in a rare moment of pop-culture infusion into his films, had the film play on a television in a scene in The Shining.

Sequel

In 1973, the film was followed up with a sequel, Class of '44, a slice-of-life film made up of vignettes about Herman Raucher and Oscar Seltzer's experiences in college prior to fighting in the Korean War. The only crew member left from Summer of '42 was Raucher himself, with a new director and composer being brought in to replace Mulligan and Legrand. Of the principal four cast members of Summer of '42, only Jerry Houser and Gary Grimes returned for prominent roles. Oliver Conant did appear in the film, albeit for less than five minutes of screen time. Jennifer O'Neill did not appear in the film at all, nor was the character of Dorothy mentioned. The film met with poor critical reviews; the only three reviews available at rottentomatoes.com are resoundingly negative,[9][10] with Channel 4 calling it "a big disappointment,"[11] and The New York Times stating "The only things worth attention in 'Class of 44' are the period details," and "'Class of '44' seems less like a movie than 95 minutes of animated wallpaper."[12]

Influence

Legrand's theme song for the film, "The Summer Knows", has since become a pop standard, being recorded by such artists as Peter Nero (who had a charting hit with his 1971 version), Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, Andy Williams, and Barbra Streisand.

The 1973 song "Summer (The First Time)" by Bobby Goldsboro has almost exactly the same subject and apparent setting, although there is no direct credited link. Bryan Adams has, however, credited the film as being a partial inspiration for his 1985 hit "Summer of '69".[13]

The Simpsons episode "Summer of 4 Ft. 2" (alternately titled 'Summer of 4'2"') was largely a parody of Summer of '42. It amalgamated scenes from another early '70s coming-of-age film, American Graffiti (both acknowledged in the DVD commentary for the episode).

There are also similarities between Summer of '42 and Malèna, another coming-of-age film set in the context of World War II, and starring Monica Bellucci and Giuseppe Sulfaro.

An episode of the 1970s sitcom Happy Days was loosely based upon Summer of '42, with Richie Cunningham befriending a Korean War widow.

In Family Guy episode "Play It Again, Brian", Brian wins an award for his essay and reads an excerpt: "She was Grace, in name and in essence. To those she loved, she exuded strength, life, laughter and light, and to me, also sorrow for circumstance that had bound her to my best friend through whom we met in the warmth and serenity of her home. Nothing from the first day I saw her and no one that has happened to me since, has ever been as frightning and as confusing, for no person I've ever known has ever done more to make me feel more sure, more insecure, more important and less significant." Later in that episode, he admits that he "ripped off" most of the essay from Summer of '42.

Remakes and re-releases

In the years since the film's release, Warner Bros. has attempted to buy back Raucher's ten percent of the film as well as his rights to the story so it could be remade; Raucher has consistently declined.[1] The 1988 film Stealing Home has numerous similarities to both Summer of '42 and Class of '44, with several incidents (most notably a subplot dealing with the premature death of the protagonist's father and the protagonist's response to it) appearing to have been directly lifted from Raucher's own life; Jennifer O'Neill stated in 2002 she believes "Home" was an attempted remake of "Summer".[14]

In 2001, Raucher consented to the film being made into an off Broadway musical play.[1] He was on hand opening night, giving the cast a pep-talk which he concluded, "We've now done it every possible way--except go out and piss it in the snow!"[15] The play met with positive critical and fan response, and was endorsed by Raucher himself, but the play was forced to close down in the aftermath of the 11 September attacks.[1] Nevertheless, the play was enough to spark interest in the film and book with a new generation, prompting Warner to re-issue the book (which had since gone out of print, along with all of Raucher's other works) for sale with Barnes & Noble's online bookstore, and to restore the film and release it on DVD.[1] The musical has since been performed across the country, at venues such as Kalliope Stage in Cleveland Heights, Ohio in 2004 (directed by Paul Gurgol) and Mill Mountain Theatre in Roanoke, Virginia, (directed by Jere Hodgin and choreographed by Bernard Monroe), and was subsequently recorded as a concert by the York Theatre Company in 2006.

In 2002, Jennifer O'Neill claimed to have obtained the rights to make a sequel to Summer of '42, based on a short story she wrote, which took place in an alternate reality in which Herman Raucher had a son and divorced his wife, went back to Nantucket in 1962 with a still-living Oscar Seltzer, and encountered Dorothy again and married her.[5] As of 2006, this project—which O'Neill had hoped to produce with Lifetime television,[16] has not been realized, and it is unknown whether O'Neill is still attempting to get it produced, or if Raucher (who technically has no say) consented to its production.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Interview with Herman Raucher by TC Palm. tcpalm.com. Retrieved July 5, 2006.

- ↑ Korean War Memorial - Oscar Seltzer koreanwar.org. Retrieved July 5, 2006.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 The Mike Douglas Show, Interview with Herman Raucher. Original date of broadcast unknown.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Raucher, Herman. Summer of '42. 23rd Edition. New York: Dell, 1974.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Interview with Jennifer O'Neill tcpalm.com. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ↑ Allmovie: Summer of '42 allmovie.com. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ↑ Internet Movie Database: Summer of '42 Business Data imdb.com Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Internet Movie Database: Summer of '42 Awards and Nominations Listing imdb.com Retrieved August 11, 2006

- ↑ Rotten Tomatoes: Class of '44 rottentomatoes.com Retrieved August 11, 2006

- ↑ Timeout Film Review: Class of '44 timeout.com Retrieved August 11, 2006,

- ↑ Channel 4 Film Reviews: Class of '44 channel4.com Retrieved August 11, 2006

- ↑ New York Times Film Review: Class of '44 nytimes.com Retrieved August 11, 2006

- ↑ Summer of '69 lyrics explained by co-author jimvallance.com Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ↑ Jennifer O'Neill in 2002 tv-now.com Retrieved August 11, 2006 Archived August 29, 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Theatermania.com, Starry, Starry Morning: Charles Nelson's Casts and Forecasts. Retrieved September 3, 2007

- ↑ Summer of '42 Plus Twenty usatoday.com. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||