The Best Years of Our Lives

| The Best Years of Our Lives | |

|---|---|

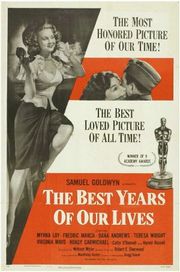

Theatrical poster |

|

| Directed by | William Wyler |

| Produced by | Samuel Goldwyn |

| Written by | Robert E. Sherwood MacKinlay Kantor |

| Starring | Fredric March Myrna Loy Dana Andrews Teresa Wright Virginia Mayo Harold Russell |

| Music by | Hugo Friedhofer |

| Cinematography | Gregg Toland |

| Editing by | Daniel Mandell |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

| Release date(s) | November 21, 1946 |

| Running time | 172 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.1 million |

| Gross revenue | $23,650,000[1] |

The Best Years of Our Lives is a 1946 American drama film about three servicemen trying to piece their lives back together after coming home from World War II. It won the 1946 Academy Award for Best Picture.

Samuel Goldwyn was inspired to produce a film about veterans after reading an August 7, 1944 article in Time magazine about the difficulties experienced by men returning to civilian life. Goldwyn hired former war correspondent MacKinlay Kantor to write a screenplay. His work was first published as a novella, Glory for Me, which Kantor wrote in blank verse.[2][3]

Robert Sherwood then adapted the novel as a screenplay.[3] The film was directed by William Wyler, with cinematography by Gregg Toland. The film won seven Academy Awards, including those for best picture, director, actor, supporting actor, editing, screenplay, and original score.

In addition to its critical success, the film quickly became a great commercial success upon release. It became the highest grossing film in both the USA and UK since the release of Gone with the Wind. It remains the sixth most attended film of all time in the UK, with over 20 million tickets sold.[4]

The ensemble cast includes Fredric March, Myrna Loy, Dana Andrews, Teresa Wright, Virginia Mayo, and Hoagy Carmichael. It also features Harold Russell, a U.S. paratrooper who had lost both hands in a training accident.

Contents |

Plot

After World War II, demobilized servicemen Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), Homer Parrish (Harold Russell), and Al Stephenson (Frederic March) meet while hitching a ride home in a bomber to Boone City, a fictional Midwestern city, patterned after Cincinnati, Ohio.[2] Fred was a decorated Army Air Forces captain and bombardier with the Eighth Air Force in Europe, who still suffers from nightmares of combat. Homer had been in the Navy, where he lost both hands from burns suffered when his aircraft carrier was sunk. For replacements, he has mechanical hook prostheses (as Harold Russell had, so no artifice was required). Al served as an infantry platoon sergeant in the 25th Infantry Division, fighting in the Pacific.

Prior to the war, Al had worked as a bank executive and loan officer for the Corn Belt Savings and Loan in Boone City. He is a mature man with a loving family and comfortable home: his patient wife Milly (Myrna Loy), adult daughter Peggy (Teresa Wright) and college freshman son Rob. Al now is having trouble readjusting to civilian life, as do his two chance acquaintances, and he is showing signs of alcoholism.

The bank, anticipating an increase in loans to returning war veterans, promotes Al to Vice President in charge of the small loan department because of his war experience. However, after he approves a chancy loan to a veteran, Al's boss Mr. Milton advises him not to gamble on further loans without collateral. At his welcome-home dinner, a slightly drunk Al gives a stirring speech, acknowledging that people will think that the bank is gambling with the depositors' money if he has his way, "And they'll be right; we'll be gambling on the future of this country!" Mr. Milton applauds his sentiments, but Al remarks later, "He'll back me up wholeheartedly until the next time I help some little guy, then I'll have to fight it out again."

Before the war, Fred had been an unskilled drugstore soda jerk, having been raised in a poor neighborhood. He does not want to return to his old job, but has no choice, given the stiff competition from other returning veterans and his lack of civilian skills. He had met Marie (Virginia Mayo) while in training and married her shortly afterward, before shipping out less than a month later. She took a job as a night club waitress and set up her own apartment while Fred was overseas. She does not relish being married to a soda jerk and seemed more attracted to Fred as an officer.

Peggy meets Fred after coming home with her father Al following an alcohol-fueled "reunion" at a local watering hole owned by Homer's uncle, Butch (Hoagy Carmichael). The relationship between Peggy and Fred begins slowly, but there is a mutual attraction almost from the start. After a double-date with Fred and Marie, Peggy is contemptuous of Marie, believing she is shallow. Peggy tells her parents she intends to break up Fred and Marie's marriage, only to be told that their own marriage overcame similar problems. To protect Peggy, Al pressures Fred to break off all contact with his daughter. Fred does so, but the friendship between the two men is strained almost to the breaking point.

Homer was a football quarterback before the war. Before leaving to fight, he had become engaged to Wilma (Cathy O'Donnell). When he returns, both Homer and his parents have trouble dealing with his disability. He does not want to burden Wilma with a handicapped man, so he pushes her away, although she adjusts best to his changed life. His uncle Butch owns a bar where the three men meet from time to time. Butch counsels Homer, but refrains from telling his nephew what to do.

At the drugstore where Fred works, an obnoxious customer, who says that the war was fought against the wrong enemies, gets into an altercation with Homer. After Fred punches the troublemaker, he loses his job. When Fred returns home, he discovers his wife with another man (Steve Cochran in an early role as another veteran). Marie exclaims:

I gave up the best years of my life, and what have you done? You flopped! Couldn't even hold that job at the drugstore. So I'm going back to work for myself and that means I'm gonna live for myself too. And in case you don't understand English, I'm gonna get a divorce.

Fred decides to leave town, and goes to his father's house to say goodbye. He gives his father, Pat Derry, his medals and citations, saying dismissively that they were "passed out with the k-rations." After he leaves, his father reads aloud the citation for Fred's Distinguished Flying Cross citation. For the first time, he learns of his son's extraordinary heroism.

Arriving at the airport, Fred books space on the first outbound transport, not caring about the destination. While waiting departure, Fred walks around the airport to kill time and wanders into a vast wartime aircraft "boneyard". Climbing into the nose of a B-17 Flying Fortress, he begins to relive intense memories of combat. The boss of a work crew interrupts him. Fred had thought of the aircraft as unwanted debris to be thrown away, like him. When the crew chief says the aluminum is being salvaged to build housing, Fred talks him into a job.

Wilma tells Homer that her family wants her to go away, since it seems that he will not marry her. He bluntly demonstrates how hard life with him would be, but she is unfazed. When she makes it clear that she loves him anyway, he gives in.

Now divorced, Fred is Homer's best man at the wedding. He greets Peggy formally, but they exchange meaningful looks throughout the ceremony. As the guests gather to congratulate Homer and Wilma, Fred approaches Peggy and holds her. He says that their life together will be a hard struggle, and it might be years before they can get ahead. She smiles despite his words and they embrace.

Cast

|

|

Casting brought together established stars as well as character actors and relative unknowns. Famed drummer Gene Krupa was seen in archival footage, while Tennessee Ernie Ford, later a famous television star, appeared as an uncredited "hillbilly singer" (in the first of his only three film appearances). At the time the film was shot, Ford was unknown as a singer. He worked in San Bernardino as a radio announcer-disc jockey. Blake Edwards, later notable as a film producer and director, appeared fleetingly as an uncredited "Corporal". Actress Judy Wyler was cast in her first role in her father's production.

Additional uncredited cast members include Mary Arden, Al Bridge, Harry Cheshire, Joyce Compton, Heinie Conklin, Clancy Cooper, Claire Du Brey, Tom Dugan, Edward Earle, Billy Engle, Pat Flaherty, Stuart Holmes, John Ince, Teddy Infuhr, Robert Karnes, Joe Palma, Leo Penn, Jack Rice, Suzanne Ridgeway, Ralph Sanford and John Tyrrell.[5]

Production

Director William Wyler had flown combat missions over Europe in filming Memphis Belle (1944) and worked hard to get accurate depictions of the combat veterans he had encountered.

For The Best Years of Our Lives, he asked the principal actors to purchase their own clothes, in order to connect with daily life and produce an authentic feeling. Other Wyler touches included constructing life-size sets, which went against the standard larger sets that were more suited to camera positions. The impact for the audience was immediate, as each scene played out in a realistic, natural way.[6]

The movie began filming on April 15, 1946 at a variety of locations, including the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden, Ontario International Airport, Ontario, California, Raleigh Studios, Hollywood and the Samuel Goldwyn/Warner Hollywood Studios. The Best Years of Our Lives is notable for cinematographer Gregg Toland's use of deep focus photography, in which objects both close to and distant from the camera are in sharp focus.[7] For the passage of Fred Derry's reliving a combat mission while sitting in the remains of a former bomber, Wyler used "zoom" effects to simulate an aircraft's taking off.[8]

The "Jackson High" football stadium seen early in the movie in aerial footage was Corcoran Stadium, the home of Xavier University's (Cincinnati) football team from 1929 to 1973.

After the war, the combat aircraft featured in the film were being destroyed and disassembled for reuse as scrap material. The scene of Derry's walking among aircraft ruins was filmed at the Ontario Army Air Field in Ontario, California. The former training facility had been converted into a scrap yard, housing nearly 2,000 former combat aircraft in various states of disassembly.[6]

Big-band jazz drummer Gene Krupa briefly appears in a montage of nightclub performers.

Reception

Upon its release, the film received extremely positive reviews from critics. Shortly after its premiere at the Astor Theater, New York, Bosley Crowther, film critic for The New York Times, hailed the film as a masterpiece. He wrote,

"It is seldom that there comes a motion picture which can be wholly and enthusiastically endorsed not only as superlative entertainment but as food for quiet and humanizing thought... In working out their solutions Mr. Sherwood and Mr. Wyler have achieved some of the most beautiful and inspiring demonstrations of human fortitude that we have had in films."[9]

He also said the ensemble casting gave the "'best' performance in this best film this year from Hollywood."

A contemporary critic, Dave Kehr, wrote,

"The film is very proud of itself, exuding a stifling piety at times, but it works as well as this sort of thing can, thanks to accomplished performances by Fredric March, Myrna Loy, and Dana Andrews, who keep the human element afloat. Gregg Toland's deep-focus photography, though, remains the primary source of interest for today's audiences."[7]

David Thomson offers tempered praise: "I would concede that Best Years is decent and humane... acutely observed, despite being so meticulous a package. It would have taken uncommon genius and daring at that time to sneak a view of an untidy or unresolved America past Goldwyn or the public."[10]

Not everyone was as complimentary. The critic Manny Farber called it "a horse-drawn truckload of liberal schmaltz."[11][12]

In July 2010, the film has a 97% "Fresh" rating at Rotten Tomatoes, based on 35 reviews.[13] Furthermore, in its "Top Critics" section, the film enjoys a 100% "Fresh" rating, based on 8 reviews.

Awards and honors

1947 Academy Awards

The film received seven Academy Awards. Fredric March won his second Best Actor award (after winning in 1932 for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). (Dana Andrews' brilliant performance turned out to be overshadowed by the acclaim Fredric March and Harold Russell received.)

Despite his Oscar-nominated performance, Harold Russell was not a professional actor. As the Academy Board of Governors considered him a long shot to win, they gave him an honorary award "for bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans through his appearance". When Russell won Best Supporting Actor, there was an enthusiastic response. He is the only actor to have received two Academy Awards for the same performance. He later sold one of the awards for $50,000, first claiming it was to pay his wife's medical bills. Later he said it was to pay for a cruise for her.[14] He often joked, "I can pick up anything but the check!"

| Award | Result | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| Best Motion Picture | Won | Samuel Goldwyn Productions (Samuel Goldwyn, Producer) |

| Best Director | Won | William Wyler |

| Best Actor | Won | Fredric March |

| Best Writing (Screenplay) | Won | Robert E. Sherwood |

| Best Supporting Actor | Won | Harold Russell |

| Best Film Editing | Won | Daniel Mandell |

| Best Music (Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture) | Won | Hugo Friedhofer |

| Best Sound Recording | Nominated | Gordon Sawyer Winner was John P. Livadary - The Jolson Story |

| Honorary Award | Won | To Harold Russell |

1947 Golden Globe Awards

- Won: Best Dramatic Motion Picture

- Won: Special Award for Best Non-Professional Acting - Harold Russell

1948 BAFTA Awards

- Won: BAFTA Award for Best Film from any Source

Other wins

- National Board of Review: NBR Award Best Director, William Wyler; 1946.

- New York Film Critics Circle Awards: NYFCC Award Best Director, William Wyler; Best Film; 1946.

- Bodil Awards: Bodil; Best American Film, William Wyler; 1948.

- Cinema Writers Circle Awards, Spain: CEC Award; Best Foreign Film, USA; 1948.

In 1989, the National Film Registry selected it for preservation in the United States Library of Congress as being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #37

- 2006 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers #11

- 2007 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #37

References

- Notes

- ↑ " 'Best Years of Our Lives' (1946)." Box Office Mojo. Retrieved: February 4, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Orriss 1984, p. 119.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Emmanuel Levy, Review: "The Best Years of Our Lives" (1946), Emmanuel Levy Website, accessed 4 May 2010

- ↑ "BFI'S Ultimate Film Chart." BFi.org.uk. Retrieved: July 27, 2010.

- ↑ " 'The Best Years of Our Lives' (1946): Full cast and credits." Internet Movie Database. Retrieved: February 4, 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Orriss 1984, p. 121.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kehr, Dave. The Best Years of Our Lives. The Chicago Reader. Retrieved: April 26, 2007.

- ↑ Orriss 1984, pp. 121–122

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley. The Best Years of our Lives. The New York Times, November 22, 1946. Retrieved: April 26, 2007.

- ↑ Thomson, 2002, p. 949.

- ↑ Flood, 1998, p. 15.

- ↑ OCLC 90715570 "Manny Farber"findarticles.com. Retrieved: April 26, 2007.

- ↑ " 'The Best Years of Our Lives'." Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved: July 30, 2010.

- ↑ Kinn and Piazza 2008, p. 332

- Bibliography

- Dolan, Edward F. Jr. Hollywood Goes to War. London: Bison Books, 1985. ISBN 0-86124-229-7.

- Flood, Richard. "Reel crank - critic Manny Farber." Artforum, Volume 37, Issue 1, September 1998. ISSN 0004-3532.

- Hardwick, Jack and Ed Schnepf. "A Viewer's Guide to Aviation Movies", in The Making of the Great Aviation Films. General Aviation Series, Volume 2, 1989.

- Kinn, Gail and Jim Piazza. The Academy Awards: The Complete Unofficial History. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2008. ISBN 978-1579127725.

- Orriss, Bruce. When Hollywood Ruled the Skies: The Aviation Film Classics of World War II. Hawthorn, California: Aero Associates Inc., 1984. ISBN 0-9613088-0-X.

- Thomson, David. "Wyler, William", A Biographical Dictionary of Film. London: Little, Brown, 2002. ISBN 0-31685-905-2.

External links

- The Best Years of Our Lives at the Internet Movie Database.

- The Best Years of Our Lives at Allmovie.

- The Best Years of Our Lives at the TCM Movie Database.

- The Best Years of Our Lives at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Best Years of Our Lives detailed synopsis/analysis at Film Site by Tim Dirks.

- The Best Years of Our Lives film article at Reel Classics. Includes MP3s.

- The Best Years of Our Lives at the Golden Years web site.

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Going My Way |

Academy Award winner for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor | Succeeded by Ben-Hur |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||