Tibeto-Burman languages

| Tibeto-Burman (debated)[1] | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

East Asia |

| Linguistic Classification: | Sino-Tibetan Tibeto-Burman (debated)[1] |

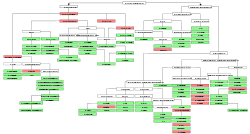

| Subdivisions: |

Mahakiranti, Magaric, Chepangic, Dura, Raji-Raute

Bodish, West Himalayish, Tamangic, Lhokpu, Lepcha, Gongduk, Tshangla

Lolo-Burmese, Mru, Naxi, Karenic, Pyu

Qiangic, Jiarongic, Sal, Nungish

Hruso, Kho-Bwa, Tani (Miric), Digaro, Midzu

"Naga": Meithei, Tangkhul, Ao, Angami-Pochuri, Zeme, Kuki-Chin

Tujia (unclassified)

? Bai (perhaps Sinitic)

? Chinese (controversial)

|

| ISO 639-5: | tbq |

The Tibeto-Burman family of languages (often considered a sub-group of the Sino-Tibetan language family) comprises languages spoken in various central, east, south and southeast Asian countries, including Burma (Myanmar), Tibet, northern Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, parts of central China (Guizhou and Hunan), northern mountains and middle hills of Nepal, eastern parts of Bangladesh (Chittagong Division), Bhutan, northern parts of Pakistan (Baltistan), and various regions of India (Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, the Ladakh and Kargil regions of Jammu and Kashmir, and North-East India). Note that while there are Tibeto-Burman languages spoken in these mentioned countries, major languages in these nations, such as Vietnamese are not Tibeto-Burman (nor even Sino-Tibetan) languages.

The family includes approximately 350 languages; Burmese has the most speakers (approximately 32 million), assuming the exclusion of Chinese. Approximately 8 million Tibetans and related peoples speak one of several related Tibetan languages.

Contents |

Scope

There are two basic conceptions of Tibeto-Burman: a rather agnostic classification of the entire family that includes the Tibetan, Burman, and Chinese languages; and a family containing the remaining languages once a supposedly divergent group such as Sinitic, Kiranti, or Karen have been split off: Tibeto-Burman vs. a containing group of Sino-Tibetan, Sino-Kiranti, or Tibeto-Karen.

In its original formation, Tibeto-Burman included Tibetan, Burmese, and Chinese. Sino-Tibetan was originally a mere change in naming adopted from the French term for Tibeto-Burman. Shafer (1966) posited Chinese as just one of several branches of an agnostic Sino-Tibetan = Tibeto-Burman, and did not use the term Tibeto-Burman at all. Benedict (1972), however, returned to older classifications of Chinese and contrasted the terms, with Tibeto-Burman being the languages left once Chinese and Karen were removed. That is, for Benedict the term 'Sino-Tibetan' indicated a hypothesis that Chinese was the first family to branch off, as his term 'Tibeto-Karen' indicated a (now abandoned) hypothesis that Karen was the next to branch off. However, the reduced Tibeto-Burman that remains has never been demonstrated to be a valid family in its own right:

The Sino-Tibetan [...] hypothesis entails that all Tibeto-Burman languages can be shown to have constituted a unity after Chinese split off, and that this must be demonstrable in the form of shared isoglosses, sound laws or morphological developments which define all of Tibeto-Burman as a unity as opposed to Sinitic. The innovations purportedly shared by all Tibeto-Burman subgroups except Chinese have never been demonstrated. In other words, no evidence has ever been adduced to support the rump ‘Tibeto-Burman’ subgroup explicitly assumed in the Sino-Tibetan phylogenetic model propagated by Paul Benedict.—Van Driem 2001:316

Van Driem proposes, as did Shafer, that Chinese not have a privileged position within the family, and that the name Tibeto-Burman be restored, as it has historical precedence.[2] He has not, however, been followed in this usage, and most linguists continue to use the term 'Sino-Tibetan' regardless of the position they assume for Chinese within the family. Most treatments, moreover, continue to follow the Sinitic–Tibeto-Burman dichotomy of Benedict and later Matisoff.

Classification

There have been two milestones in the classification of Tibeto-Burman languages, Shafer (1966) and Benedict (1972).

Shafer (1966-1974)

Shafer's tentative classification takes an agnostic position and does not promote any one branch to primary status. Rather, Chinese (Sinitic) is placed on the same level as the other branches, and Shafer's Sino-Tibetan is a synonym of Tibeto-Burman. He retained Daic within the family, allegedly at the insistence of colleagues, despite his personal belief that they were not related.

- Sino-Tibetan (= Tibeto-Burman)

- I. Sinitic

- II. ?? Daic

- III. Bodic

- a. Bodish

- i. Gurung

- ii. Tshangla

- iii. Gyarong

- iv. Tibetan

- b. West Himalayish

- (incl. Thangmi, Baram, Raji-Raute)

- c. West Central (Magar, Chepang, Hayu [misplaced])

- d. East Himalayish

- (also Newari, incertae sedis)

- a. Bodish

- IV. Burmic

- V. Baric

- VI. Karenic

Benedict (1972)

A very influential, although also tentative, classification is that of Benedict (1972). This was a collaborated effort of Paul Benedict and Robert Shafer (completed around 1942-1943) that introduced a terminological distinction between Sino-Tibetan and Tibeto-Burman.

- Sino-Tibetan

- Chinese

- Tibeto-Karen

- Karen

- Tibeto-Burman

The Tibeto-Burman family is then divided into seven primary branches:

I. Tibetan-Kanauri (aka Bodish-Himalayish)

- A. Bodish

- (Tibetan, Gyarung, Takpa, Tsangla, Murmi & Gurung)

- B. Himalayish

- i. "major" Himalayish

- ii. "minor" Himalayish

- (Rangkas, Darmiya, Chaudangsi, Byangsi)

- (perhaps also Dzorgai, Lepcha, Magari)

II. Bahing-Vayu

- A. Bahing (Sunwar, Khaling)

- B. Khambu (Sampang, Rungchenbung, Yakha, and Limbu)

- C. Vayu-Chepang

- (perhaps also Newari)

III. Abor-Miri-Dafla

- (perhaps also Aka, Digaro, Miju, and Dhimal)

IV. Kachin

- (perhaps including Luish)

V. Burmese-Lolo

- A. Burmese-Maru

- B. Southern Lolo

- C. Northern Lolo

- D. Kanburi Lawa

- E. Moso

- F. Hsi-fan (Qiangic and Jiarongic languages apart from Qiang and Gyarung themselves)

- G. Tangut

- (perhaps also Nung)

VI. Bodo-Garo (aka Barish)

- (Perhaps also "Naked Naga" aka Konyak)

VII. Kuki-Naga (aka Kukish)

- (perhaps also Karbi, Meithei, Mru)

Matisoff

Perhaps the best known is that of James Matisoff, a modification of Benedict that demoted Karen but kept the divergent position of Sinitic.

- Sino-Tibetan

- Chinese

- Tibeto-Burman

Tibeto-Burman is then divided into several branches, some of them geographic conveniences rather than linguistic proposals:

- Kamarupan (geographic)

- Kuki-Chin-Naga (geographic)

- Abor-Miri-Dafla

- Bodo-Garo

- Himalayish (geographic)

- Maha-Kiranti (includes Nepal Bhasa, Magar, Rai)

- Tibeto-Kanauri (includes Lepcha)

- Qiangic

- Jingpho-Nungish-Luish

- Jingpho

- Nungish

- Luish

- Lolo-Burmese-Naxi

- Karenic

- Baic

- Tujia (unclassified)

Matisoff makes no claim that the families in the Kamarupan or Himalayish branches have a special relationship to one another other than a geographic one. They are intended rather as categories of convenience pending more detailed comparative work.

Bradley (1997)

Since Benedict (1972), many languages previously inadequately documented have received more attention with the publication of new grammars, dictionaries, and wordlists. This new research has greatly benefited comparative work, and Bradley (1997) incorporates much of the newer data.[3]

I. Western (= Bodic)

- A. Tibetan/Kanauri

- i. Tibetan

- ii. Gurung

- iii. East Bodic (incl. Tsangla)

- iv. Kanauri

- B. Himalayan

- i. Eastern (Kiranti)

- ii. Western (Newari, Chepang, Magar, Thangmi, Baram)

II. Sal

- A. Baric (Bodo-Garo–Northern Naga)

- B. Jinghpaw

- C. Luish (incl. Pyu)

- D. Kuki-Chin (incl. Meithei and Karbi)

III. Central (perhaps a residual group, not actually related to each other. Lepcha may also fit here.)

- A. Adi-Galo-Mishing-Nishi

- B. Mishmi (Digarish and Keman)

- C. Rawang

IV. North-Eastern

- A. Qiangic

- B. Naxi–Bai

- C. Tujia

- D. Tangut

V. South-Eastern

- A. Burmese-Lolo (incl. Mru)

- B. Karen

Van Driem (2001)

Like Matisoff, George van Driem (2001) acknowledges that the relationships of the "Kuki-Naga" languages (Kuki, Mizo, Meitei, etc.), both amongst each other and to the other Tibeto-Burman languages, remain unclear. However, rather than placing them in a geographic grouping, as Matisoff does, van Driem leaves them unclassified.

Van Driem proposes that Chinese owes its traditional privileged place in Sino-Tibetan to historical, typological, and cultural rather than linguistic criteria. For example, he notes that Lepcha is as difficult to reconcile with Tibeto-Burman reconstructions as Chinese is, but that no-one has proposed a "Lepcha-Tibetan" family with Lepcha as one of two primary branches. He compares the situation to the Indo-Hittite hypothesis in Indo-European studies.

Van Driem's classification goes further than simply demoting Chinese to a branch of Tibeto-Burman: he proposes that the closest relatives of Chinese are Bodic languages such as Tibetan, a hypothesis called Sino-Bodic. Critics counter that Van Driem hasn't produced any evidence that Chinese and Bodic share innovations that set them apart as a group. (Note also that most other linguists who merge Chinese into Tibeto-Burman continue to call the resulting family Sino-Tibetan.)

Tibeto-Burman (Van Driem)

- Brahmaputran

- Dhimal

- Bodo-Koch

- Konyak

- Kachin-Luic

- Southern Tibeto-Burman

- Lolo-Burmese

- Karenic

- Sino-Bodic

- Sinitic

- Bodish-Himalayish

- Kirantic

- Tamangic

- (several isolates within Sino-Bodic)

- A number of other small families and isolates as primary branches of Tibeto-Burman

(Nepal Bhasa, Qiang, Nung, Magar, Chakma etc.)

There are in addition poorly known languages, such as Ayi, which may be closely related to others but remain unclassified.

References

- ↑ Cf. Beckwith, Christopher I. 1996. "The Morphological Argument for the Existence of Sino-Tibetan." Pan-Asiatic Linguistics: Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Languages and Linguistics, January 8-10, 1996. Vol. III, pp. 812-826. Bangkok: Mahidol University at Salaya.

- ↑ Van Driem, George "Tibeto-Burman Phylogeny and Prehistory: Languages, Material Culture and Genes". Bellwood, Peter & Renfrew, Colin (eds) Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis (2003), Ch 19.

- ↑ David Bradley (2002) "The Subgrouping of Tibeto-Burman", in Chris Beckwith, Henk Blezer, eds., Medieval Tibeto-Burman Languages. Brill.

Bibliography

- Benedict, Paul K. (1972). Sino-Tibetan: A conspectus. J. A. Matisoff (Ed.). Cambridge: The University Press. ISBN 0-521-08175-0.

- Bielmeier, Roland and Haller, Felix (eds.), Linguistics of the Himalayas and Beyond, Berlin and New York, Mouton de Gruyter, 2007. ISBN 978-3-11-019828-7

- Bradley, David. (1997). Tibeto-Burman languages and classification. In D. Bradley (Ed.), Papers in South East Asian linguistics: Tibeto-Burman languages of the Himalayas (No. 14, pp. 1-71). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Shafer, Robert. (1966). Introduction to Sino-Tibetan (Part 1). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Shafer, Robert. (1967). Introduction to Sino-Tibetan (Part 2). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Shafer, Robert. (1968). Introduction to Sino-Tibetan (Part 3). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Shafer, Robert. (1970). Introduction to Sino-Tibetan (Part 4). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Shafer, Robert. (1974). Introduction to Sino-Tibetan (Part 5). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||