Xerxes I of Persia

| Xerxes the Great | |

|---|---|

| Khshayathiya Khshayathiyanam, King of Kings | |

|

|

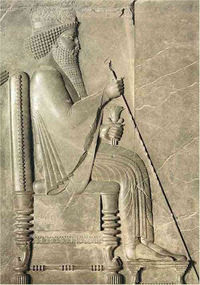

| Artistic depiction of Xerxes | |

| Reign | 486 to 465 BC |

| Coronation | October 485 BC |

| Born | 519 BC |

| Birthplace | Persia |

| Died | 465 BC (aged 54) |

| Place of death | Persia |

| Buried | Persia |

| Predecessor | Darius I |

| Successor | Artaxerxes I |

| Consort | Amestris |

| Royal House | Achaemenid |

| Father | Darius I of Persia (the Great) |

| Mother | Atossa |

| Religious beliefs | Zoroastrianism |

Xerxes I of Persia (English: /ˈzɜrksiːz/; Old Persian: خشایارشا (Ḫšayāršā), IPA: [xʃajaːrʃaː]; also known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth Zoroastrian king of kings of the Achamenid Empire.

Contents |

Life

Youth and rise to power

Immediately after seizing the kingship, Darius I of Persia (son of Hystaspes) married Atossa (daughter of Cyrus the Great). They were both descendants of Achaemenes from different Achaemenid lines. Marrying a daughter of Cyrus strengthened Darius' position as king.[1] Darius was an active emperor, busy with building programs in Persepolis, Susa, Egypt, and elsewhere. Toward the end of his reign he moved to punish Athens, but a new revolt in Egypt (probably led by the Persian satrap) had to be suppressed. Under Persian law, the Achaemenian kings were required to choose a successor before setting out on such serious expeditions. Upon his great decision to leave (487-486 BC),[2] Darius prepared his tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam and appointed Xerxes, his eldest son by Atossa, as his successor. Darius' failing health then prevented him from leading the campaigns,[3] and he died in October 486 BC.[3]

Xerxes was not the oldest son of Darius and according to old Iranian traditions should not have succeeded the King. Xerxes was however the oldest son of Darius and Atossa hence descendent of Cyrus. This made Xerxes the chosen King of Persia.[4] Some modern scholars also view the unusual decision of Darius to give the throne to Xerxes to be a result of his consideration of the unique positions that Cyrus the Great and his daughter Atossa have had.[5] Artobazan was born to "Darius the subject", while Xerxes was the eldest son born in the purple after Darius' rise to the throne, and Artobazan's mother was a commoner while Xerxes' mother was the daughter of the founder of the empire.[6]

Xerxes was crowned and succeeded his father in October-December 486 BC[7] when he was about 36 years old.[2] The transition of power to Xerxes was smooth due again in part to great authority of Atossa[1] and his accession of royal power was not challenged by any person at court or in the Achaemenian family, or any subject nation.[8]

Almost immediately, he suppressed the revolts in Egypt and Babylon that had broken out the year before, and appointed his brother Achaemenes as governor or satrap (Old Persian: khshathrapavan) over Egypt. In 484 BC, he outraged the Babylonians by violently confiscating and melting down[9] the golden statue of Bel (Marduk, Merodach), the hands of which the rightful king of Babylon had to clasp each New Year's Day. This sacrilege led the Babylonians to rebel in 484 BC and 482 BC, so that in contemporary Babylonian documents, Xerxes refused his father's title of King of Babylon, being named rather as King of Persia and Media, Great King, King of Kings (Shahanshah) and King of Nations (i.e. of the world).

Although Herodotus' report in the Histories has created certain problems concerning Xerxes' religious beliefs, modern scholars consider him as a Zoroastrian.[10]

Death

In the year 465 BC Xerxes was murdered by Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard and the most powerful official in Persian court (Hazarapat/commander of thousand). He was promoted to this most prestigious of positions in Achamenid court after his refusal to help Mardonius in Plataea and instead withdrawing the second Persian army successfully out of Greece. Although he bore the same name as famed uncle of Xerxes, a Hyrcanian, his rise to prominence was due to his popularity in religious quarters of the court and harem intrigues. He put his seven sons in key positions and had an effective master plan to dethrone the Achamenids.[11] In August, 465 B.C he assassinated Xerxes with the help of a eunuch Aspamitres. Greek historians give contradicting accounts on the full story. According to Ctesias (in Persica 20), he then accused the crown prince Darius (Xerxes' eldest son) of the murder; he instigated Artaxerxes (another of Xerxes' son), to avenge the patricide. But according to Aristotle (in Politics 5.1311b), Artabanus killed Darius first and then the king himself. Later on after discovering what he had done and planned for the royal power, Artabanus together with his sons were killed by Artaxerxes I.[12] Participating in the scuffles was also general Megabyzus (baghabukhsha) whose side switching probably saved the day for the Achamenids.[13]

Campaigns

Invasion of the Greek mainland

Darius left to his son the task of punishing the Athenians, Naxians, and Eretrians for their interference in the Ionian Revolt and their victory over the Persians at Marathon. From 483 BC Xerxes prepared his expedition: A channel was dug through the isthmus of the peninsula of Mount Athos, provisions were stored in the stations on the road through Thrace, two bridges were built across the Hellespont. Soldiers of many nationalities served in the armies of Xerxes, including the Assyrians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Egyptians, Jews, and Arabs.[14]

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Xerxes' first attempt to bridge the Hellespont ended in failure when a storm destroyed the flax and papyrus bridge; Xerxes ordered the Hellespont (the strait itself) whipped three hundred times and had fetters thrown into the water. Xerxes' second attempt to bridge the Hellespont was successful.[15] Xerxes concluded an alliance with Carthage, and thus deprived Greece of the support of the powerful monarchs of Syracuse and Agrigentum. Many smaller Greek states, moreover, took the side of the Persians, especially Thessaly, Thebes and Argos. Xerxes set out in the spring of 480 BC from Sardis with a fleet and army which Herodotus claimed was more than two million strong with at least 10,000 elite warriors named Persian Immortals. Xerxes was victorious during the initial battles.

Thermopylae and Athens

At the Battle of Thermopylae, a small force of Greek warriors led by King Leonidas of Sparta resisted the much larger Persian forces, but were ultimately defeated. According to Herodotus, the Persians broke the Spartan phalanx after a Greek man called Ephialtes betrayed his country by telling the Persians of another pass around the mountains. After Thermopylae, Athens was captured and the Athenians and Spartans were driven back to their last line of defense at the Isthmus of Corinth and in the Saronic Gulf. The delay caused by the Spartans allowed Athens to be evacuated.

What happened next is a matter of some controversy. According to Herodotus, upon encountering the deserted city, in an uncharacteristic fit of rage particularly for Persian kings, Xerxes had Athens burned. He almost immediately regretted this action and ordered it rebuilt the very next day. However, Persian scholars dispute this view as pan-Hellenic propaganda , arguing that Sparta, not Athens, was Xerxes' main foe in his Greek campaigns, and that Xerxes would have had nothing to gain by destroying a major center of trade and commerce like Athens once he had already captured it.

At that time, anti-Persian sentiment was high among many mainland Greeks, and the rumor that Xerxes had destroyed the city was a popular one, though it is equally likely the fire was started by accident as the Athenians were frantically fleeing the scene in pandemonium, or that it was an act of "scorched earth" warfare to deprive Xerxes' army of the spoils of the city.

At Artemisium, large storms had destroyed ships from the Greek side and so the battle stopped prematurely as the Greeks received news of the defeat at Thermopylae and retreated. Xerxes was induced by the message of Themistocles (against the advice of Artemisia of Halicarnassus) to attack the Greek fleet under unfavourable conditions, rather than sending a part of his ships to the Peloponnesus and awaiting the dissolution of the Greek armies. The Battle of Salamis (September 29, 480 BC) was won by the Greek fleet, after which Xerxes set up a winter camp in Thessaly.

Due to unrest in Babylon, Xerxes was forced to send his army home to prevent a revolt, leaving behind an army in Greece under Mardonius, who was defeated the following year at Plataea.[17] The Greeks also attacked and burned the remaining Persian fleet anchored at Mycale. This cut off the Persians from the supplies they needed to sustain their massive army, and they had no choice but to retreat. Their withdrawal roused the Greek city-states of Asia.

Construction projects

After the military blunders in Greece, Xerxes returned to Persia and completed the many construction projects left unfinished by his father at Susa and Persepolis. He built the Gate of all Nations and the Hall of a Hundred Columns at Persepolis, which are the largest and most imposing structures of the palace. He completed the Apadana, the Palace of Darius and the Treasury all started by Darius as well as building his own palace which was twice the size of his father's. His taste in architecture was similar to that of Darius, though on an even more gigantic scale.[18] He also maintained the Royal Road built by his father and completed the Susa Gate and built a palace at Susa.[19]

In classical music

Xerxes is the protagonist of the opera Serse by the German-English Baroque composer George Frideric Handel. It was first performed in King's Theatre in London on 15 April 1738. The famous aria, "Ombra mai fù" is taken from the opera.

Children

By queen Amestris

- Amytis, wife of Megabyzus

- Artaxerxes I

- Darius, the first born, murdered by Artaxerxes I and Artabanus.

- Hystaspes, murdered by Artaxerxes I.

- Achaemenes, murdered by Egyptians.

- Rhodogune

By unknown wives

- Artarius, satrap of Babylon.

- Tithraustes

- Arsames or Arsamenes or Arxanes or Sarsamas satrap of Egypt.

- Parysatis[20]

- Ratashah[21]

Depictions in popular culture

Later generations' fascination with ancient Sparta, and particularly the Battle of Thermopylae, has led to Xerxes' portrayal in a number of works of popular culture. For instance, he was played by David Farrar in the 1962 film The 300 Spartans, where he is portrayed as a cruel, power-crazed despot and an inept commander. He also features prominently in the graphic novel 300 by Frank Miller, as well as the movie adaptation (portrayed by Brazilian actor Rodrigo Santoro).

Other works dealing with the Persian Empire or the Biblical story of Esther have also referenced Xerxes, such as the video game Assassin's Creed II and the film One Night with the King, in which Ahasueras (Xerxes) was portrayed by British actor Luke Goss. He is the leader of the Persian Empire in the video game Civilization II (along with Scheherazade) and III, although Civilization IV replaces him with Cyrus the Great.

|

Xerxes I of Persia

Born: 519 BC Died: 465 BC |

||

| Preceded by Darius I the Great |

Great King (Shah) of Persia 485 BC–465 BC |

Succeeded by Artaxerxes I |

| Pharaoh of Egypt 485 BC–465 BC |

||

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Schmitt, R., Atossa in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dandamaev, M. A., A political history of the Achaemenid empire, p. 180.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 A. Sh. Shahbazi, Darius I the Great, in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Herodotus Book 7, Chap. 2. Excerpt: Artabazanes claimed the crown as the eldest of all the children, because it was an established custom all over the world for the eldest to have the pre-eminence; while Xerxes, on the other hand, urged that he was sprung from Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus, and that it was Cyrus who had won the Persians their freedom.

- ↑ R. Shabani Chapter I, p. 15

- ↑ Olmstead: the history of Persian empire

- ↑ The cambridge history of Iran vol. 2. p. 509.

- ↑ The Cambridge ancient history vol. V p. 72.

- ↑ R. Ghirshman, Iran, p.191

- ↑ M. Boyce, Achaemenid Religion in Encyclopædia Iranica. See also Boardman, J.; et al. (1988). The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. IV (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521228042. p. 101.

- ↑ Iran-e-Bastan/Pirnia book 1 p 873

- ↑ Dandamayev

- ↑ History of Persian Empire-Olmstead p 289/90

- ↑ Farrokh 2007: 77

- ↑ Bailkey, Nels, ed. Readings in Ancient History, p. 175. D.C. Heath and Co., USA, 1992.

- ↑ Livius Picture Archive: Persepolis - Apadana Audience Relief

- ↑ Battle of Salamis and aftermath

- ↑ Ghirshman, Iran, p.172

- ↑ Herodotus VII.11

- ↑ Ctesias

- ↑ M. Brosius, Women in ancient Persia.

- Gore Vidal, in his historical fiction novel Creation, describes at length the rise of Achemenids, and especially Darius I and presents the life and death circumstances of Xerxes. His vision of history goes against the grain of Greek histories.

References

Ancient sources

The Sixth Book, Entitled Erato in History of Herodotus.

The Sixth Book, Entitled Erato in History of Herodotus. The Seventh Book, Entitled Polymnia in History of Herodotus.

The Seventh Book, Entitled Polymnia in History of Herodotus.

Modern sources

- Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A political history of the Achaemenid empire. Brill Publishers. pp. 373. ISBN 9004091726.

- The Histories. Spark Educational Publishing. 2004. ISBN 1593081022.

- Shabani, Reza (1386 AP) (in Persian). Khshayarsha (Xerxes). What do I know about Iran? No. 75. Cultural Research Burreau. pp. 120. ISBN 9643791092.

- Shahbazi, A. Sh.. "Darius I the Great". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 7. Routledge & Kegan Paul. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v7f1/v7f136a.html#iii.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Achaemenid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 3. Routledge & Kegan Paul. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v1f4/v1f4a109.html.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Atossa". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 3. Routledge & Kegan Paul. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v3f1/v3f1a014.html.

- McCullough, W. S. "Ahasuerus". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 1. Routledge & Kegan Paul. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v1f6/v1f6a062.html.

- Boyce, Mary. "Achaemenid Religion". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 1. Routledge & Kegan Paul. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v1f4/v1f4a110.html.

- Dandamayev, M. A (1999). "Artabanus". Encyclopædia Iranica. Routledge & Kegan Paul. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v2f6/v2f6a002.html. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- Frye, Richard N. (1963). The Heritage of Persia. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 301. ISBN 0297167278.

- Schmeja, H. (1975). "Dareios, Xerxes, Artaxerxes. Drei persische Königsnamen in griechischer Deutung (Zu Herodot 6,98,3)". Die Sprache 21: pp. 184–88.

- Gershevitch, Ilya; Bayne Fisher, William; A. Boyle, J. (1985). The Cambridge history of Iran. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200911.

- Boardman, John; al., et (1988). The Cambridge ancient history. V. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521228042.