Zulu

.jpg) |

||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10,659,309 (2001 census)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||

|

Zulu |

||||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||

|

Christian, African Traditional Religion |

||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||

|

Bantu · Nguni · Basotho · Xhosa · Swazi · Matabele · Khoisan · Afro-Iranians |

| person | umZulu |

| people | amaZulu |

| language | isiZulu |

| country | kwaZulu |

The Zulu (Zulu: amaZulu) are the largest South African ethnic group of an estimated 10–11 million people who live mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Small numbers also live in Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Mozambique. Their language, Zulu, is a Bantu language; more specifically, part of the Nguni subgroup. The Zulu Kingdom played a major role in South African history during the 19th and 20th centuries. Under apartheid, Zulu people were classed as third-class citizens and suffered from state-sanctioned discrimination. They remain today the most numerous ethnic group in South Africa, and now have equal rights along with all other citizens.

Contents |

Origins

The Zulu were originally a major clan in what is today Northern KwaZulu-Natal, founded ca. 1709 by Zulu kaNtombhela. In the Nguni languages, iZulu/iliZulu/liTulu means heaven, or sky. [2] At that time, the area was occupied by many large Nguni communities and clans (also called isizwe=nation, people or isibongo=clan). Nguni communities had migrated down Africa's east coast over thousands of years, as part of the Bantu migrations probably arriving in what is now South Africa in about the 9th century A.D.

_crop.png)

Kingdom

The Zulu formed a powerful state in 1816 under the leader Shaka. Shaka, as the Zulu King, gained a large amount of power over the tribe. As commander in the army of the powerful Mthethwa Empire, he became leader of his mentor Dingiswayo's paramountcy and united what was once a confederation of tribes into an imposing empire under Zulu hegemony.

Conflict with the British

On December 11, 1878, agents of the British delivered an ultimatum to 11 chiefs representing Cetshwayo. The terms forced upon Cetshwayo required him to disband his army and accept British authority. Cetshwayo refused, and war followed at the start of 1879. During the war, the Zulus defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana on January 22. The British managed to get the upper hand after the battle at Rorke's Drift, and win the war with the Zulu defeat at the Battle of Ulundi on July 4.

Absorption into Natal

After Cetshwayo's capture a month after his defeat, the British divided the Zulu Empire into 13 "kinglets". The subkingdoms fought amongst each other until 1883 when Cetshwayo was reinstated as king over Zululand. This still did not stop the fighting and the Zulu monarch was forced to flee his realm by Zibhebhu, one of the 13 kinglets, supported by Boer mercenaries. Cetshwayo died in February 1884, possibly poisoned, leaving his son, the 15 year-old Dinuzulu, to inherit the throne. In-fighting between the Zulu continued for years, until Zululand was absorbed fully into the British colony of Natal.

Apartheid years

KwaZulu homeland

Under apartheid, the homeland of KwaZulu (Kwa meaning place of) was created for Zulu people. In 1970, the Bantu Homeland Citizenship Act provided that all Zulus would become citizens of KwaZulu, losing their South African citizenship. KwaZulu consisted of a large number of disconnected pieces of land, in what is now KwaZulu-Natal. Hundreds of thousands of Zulu people living on privately owned "black spots" outside of KwaZulu were dispossessed and forcibly moved to bantustans – worse land previously reserved for whites contiguous to existing areas of KwaZulu – in the name of "consolidation." By 1993, approximately 5.2 million Zulu people lived in KwaZulu, and approximately 2 million lived in the rest of South Africa. The Chief Minister of KwaZulu, from its creation in 1970 (as Zululand) was Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi. In 1994, KwaZulu was joined with the province of Natal, to form modern KwaZulu-Natal.

Inkatha YeSizwe

Inkatha YeSizwe means "the crown of the nation". In 1975, Buthelezi revived the Inkatha YaKwaZulu, predecessor of the Inkatha Freedom Party. This organization was nominally a protest movement against apartheid, but held more conservative views than the ANC. For example, Inkatha was opposed to the armed struggle, and to sanctions against South Africa. Inkatha was initially on good terms with the ANC, but the two organizations came into increasing conflict beginning in 1979 in the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising.

Modern Zulu population

The modern Zulu population is fairly evenly distributed in both urban and rural areas. Although KwaZulu-Natal is still their heartland, large numbers have been attracted to the relative economic prosperity of Gauteng province. Indeed, Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in the province, followed by Sotho. Zulu is also widely spoken in rural and small-town Mpumalanga province.

Zulus also play an important part in South African politics. Mangosuthu Buthelezi served a term as Minister of Home Affairs in the government of national unity which came into power in 1994, when reduction of civil conflict between ANC and IFP followers was a key national issue. Within the country, South African President Jacob Zuma and former Deputy President Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka of the country are Zulu, in part to bolster the ruling ANC's claim to be a pan-ethnic national party and refute IFP claims that it was primarily a Xhosa party.

Language

The language of the Zulu people is "isiZulu", a Bantu language; more specifically, part of the Nguni subgroup. Zulu is the most widely spoken language in South Africa, where it is an official language. More than half of the South African population are able to understand it, with over 9 million first-language and over 15 million second-language speakers.[3] Many Zulu people also speak Afrikaans, English, Portuguese, Shangaan, Sesotho and others from among South Africa's 11 official languages.

Clothing

Zulus wear a variety of costumes. For example, the males may wear a suit and tie (example) with leather shoes for formal occasions, whereas casual attire is more likely to consist of jeans and a T-shirt, possibly with trainers on the feet. In hot weather they may wear shorts. In cold weather they may wear a coat. When it is raining, they may wear a waterproof jacket, or carry an umbrella. Underwear consists of socks for both sexes, together with underpants for males, or knickers and a bra for females. Infants will usually wear nappies.

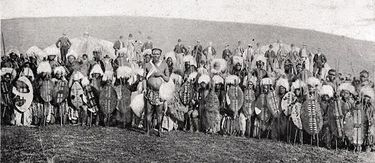

Traditional male clothing is usually light, consisting of a two-part apron (similar to a loincloth) used to cover the genitals and buttocks. The front piece is called the umutsha (pronounced [umuːtʃa]), and is usually made of springbok or other animal hide twisted into different bands which cover the genitals. The rear piece, called the ibheshu [ibeːʃu], is made of a single piece of springbok or cattle hide, and its length is usually used as an indicator of age and social position; longer amabheshu (plural of ibheshu) are worn by older men. Married men will usually also wear a headband, called the umqhele [um!ʰɛle], which is usually also made of springbok hide, or leopard hide by men of higher social status, such as chiefs. Zulu men will also wear cow tails as bracelets and anklets called imishokobezi [imiʃoɠoɓɛːzi] during ceremonies and rituals, such as weddings or dances.

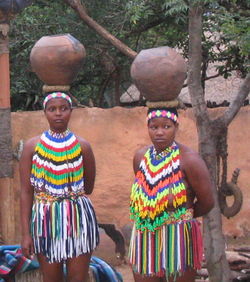

The women on the other hand dress differently depending on whether they are single, engaged and married. An unmarried woman who is still eligible is proud of her body and is not ashamed of showing it. She only wears a short skirt made of grass or beaded cotton strings and spruces herself up with lots of beadwork. An engaged woman will let her traditionally short hair grow. She will cover her bosom with a decorative cloth which is done out of respect for her future relatives and to indicate that she has been spoken for. The married woman covers her body completely signalling to other men that she is taken.

Religion and beliefs

Most Zulu people state their beliefs to be Christian. Some of the most common churches to which they belong are African Initiated Churches, especially the Zion Christian Church and various Apostolic Churches, although membership of major European Churches, such as the Dutch Reformed, Anglican and Catholic Churches is also common. Nevertheless, many Zulus retain their traditional pre-Christian belief system of ancestor worship in parallel with their Christianity.

Zulu religion includes belief in a creator God (Unkulunkulu) who is above interacting in day-to-day human affairs, although this belief appears to have originated from efforts by early Christian missionaries to frame the idea of the Christian God in Zulu terms.[4] Traditionally, the more strongly held Zulu belief was in ancestor spirits (Amatongo or Amadhlozi), who had the power to intervene in people's lives, for good or ill.[5] This belief continues to be widespread among the modern Zulu population.[6]

In order to appeal to the spirit world, a diviner (sangoma) must invoke the ancestors through divination processes to determine the problem. Then, a herbalist (inyanga) prepares a mixture to be consumed (muthi) in order to influence the ancestors. As such, diviners and herbalists play an important part in the daily lives of the Zulu people. However, a distinction is made between white muthi (umuthi omhlope), which has positive effects, such as healing or the prevention or reversal of misfortune, and black muthi (umuthi omnyama), which can bring illness or death to others, or ill-gotten wealth to the user.[6] Users of black muthi are considered witches, and shunned by society.

Christianity had difficulty gaining a foothold among the Zulu people, and when it did it was in a syncretic fashion. Isaiah Shembe, considered the Zulu Messiah, presented a form of Christianity (the Nazareth Baptist Church) which incorporated traditional customs.[7]

Notable Zulus

- Credo Mutwa - Spiritual leader of the Zulu people.

- Pixley ka Isaka Seme - Founder of African National Congress and the first black lawyer in South Africa.

- Jacob Zuma - President of the Republic of South Africa.

- Chief Albert Luthuli - President of the African National Congress and first South African Nobel Peace laureate.

- King Shaka ka Senzangakhona - Founder of the Zulu Nation

- Princess Constance Magogo Sibilile Mantithi Ngangezinye kaDinuzulu - Artist and Zulu Princess

- Professor Njabulo Ndebele - Author and Academic

- John Langalibalele Dube - first President of the African National Congress, founder of Ohlange Institute, Educator.

See also

- Inkatha Freedom Party

- List of Zulu kings

- List of Zulus

- Nguni

- Shaka Zulu

- Zulu language

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 South Africa grows to 44.8 million, on the site southafrica.info published for the International Marketing Council of South Africa, dated 9 July 2003, retrieved 4 March 2005.

- ↑ "People of Africa: Tuareg". African Holocaust Society. http://www.africanholocaust.net/peopleofafrica.htm#zulu. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ "Ethnologue report for language code ZUL". Ethnologue. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=zul.

- ↑ Irving Hexham (1979). "Lord of the Sky-King of the Earth: Zulu traditional religion and belief in the sky god". Studies in Religion (University of Waterloo). http://www.ucalgary.ca/~nurelweb/papers/irving/skyking.html. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ Henry Callaway (1870). "Part I:Unkulunkulu". The Religious System of the Amazulu. Springvale. http://www.sacred-texts.com/afr/rsa/index.htm.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Adam Ashforth (2005). "Muthi, Medicine and Witchcraft: Regulating ‘African Science’ in Post-Apartheid South Africa?". Social Dynamics 31:2.

- ↑ "Art & Life in Africa Online - Zulu". University of Iowa. http://www.uiowa.edu/~africart/toc/people/Zulu.html. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

External links

- History section of the official page for the Zululand region, Zululand.kzn.org

- Human Rights Watch report on KwaZulu, just prior to the 1994 elections. – This includes detailed, well-referenced sections on recent Zulu history. hrw.org

- People of Africa, Zulu marriage explained, africanholocaust.net

- Izithakazelo, wakahina.co.za

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||